A Beginner’s Guide to Identifying Explosive Ordnance in Social Media Imagery

Note: Explosive ordnance (EO) are extremely dangerous. Never approach them unless you are explicitly trained to do so. When posting about potentially explosive objects online, do not encourage others to interact with them. If you come across any potential EO, call the police or other relevant authorities.

Landmines, rockets, bombs, grenades and other explosive weapons that were fired but did not explode can remain dangerous for decades after wars and conflicts end.

Commonly known as unexploded ordnance (UXO), these weapons can detonate without warning, killing or injuring civilians long after conflicts have ended.

Global estimates vary, but in 2023, the Landmine Monitor recorded 4,710 people injured or killed by landmines and explosive remnants of war. In Ukraine alone, between February 2022 and May 2023, the HALO trust identified 855 civilians that were hurt or killed in 550 mine-related accidents.

The rise of conflict imagery on social media has provided civil society and researchers valuable material to identify explosive ordnance (EO), including UXO. However, this has also increased the risk of misinformation and disinformation surrounding weapons use. Misidentifications of EO can result in fake narratives spreading online, false accusations in times of war, and physical harm or death to individuals during clearance efforts.

What this guide covers

EO is defined by Oxford Reference as “any munition that contains explosives, including bombs and warheads; guided and ballistic missiles; artillery, mortar, rocket, and small arms ammunition; mines, torpedoes, and depth and demolition charges”.

This guide aims to provide a starting point to decipher the origin and characteristics of EO featured in social media imagery as accurately as possible. Doing so can provide evidence to counter false or harmful narratives, and assist with post-conflict clean up efforts.

There are many different types of EO, but this guide will focus on how to identify some of the more commonly seen ones, with reference to existing open-source resources that can be found online. We have compiled a list of some of the most useful online resources for this purpose, which you will find at the end of this guide.

We will not cover naval ordnance as these are very rarely found in social media imagery, except for the occasionally washed up anti-ship mine.

The guide also focuses on UXO found as complete objects, and does not include detailed analysis of remnant pieces of shrapnel after explosive ordnance has detonated and functioned as designed, or craters and damage left from such weapons. While it may be possible to identify EO post-detonation based on clues such as visible text, and some of the tips in this guide can also be applied to such cases, this is generally more difficult than for intact objects.

It is important to note that online identifications of munitions are always preliminary and will need to be followed by thorough comparisons and checks.

Starting your investigation

The first step in investigating any online imagery is to ensure that it is authentic. Any imagery or content online could be altered or posted with misleading information, which could result in a misidentification of EO or the spread of false information. Thus, verifying the authenticity and originality of any content is important before exerting time and effort to identify any munitions visible in the imagery. You can refer to Bellingcat’s guide to social media verification for advice on how to get started with this.

If the item in the imagery is high enough resolution and not damaged or dirty, a reverse image search can be a good next step. This can reveal previous efforts to verify the same image, as well as potential matches for the type or model of the weapon shown. Reverse image searches are not limited to Google – Bellingcat has detailed the core differences between several reverse image search engines and outlined strategies for using them for investigations here.

Before investigating further you may also want to first check the Open Source Munitions Portal, which has hundreds of verified images of EO which you can search through based on where and when the images were reported to have been taken.

Identifying features

Once you have established that the image is authentic and that the object it shows has not been previously identified, a closer examination can often provide clues on what the object shown is.

- Text

Very often larger munitions will be labelled or stamped with the exact model type and other information, such as manufacture date and production lot. If any writing is visible on the item or any other related objects nearby, such as ammunition crates, this can be an easy way to decipher the exact model.

For example, weapons produced by NATO countries would typically carry a CAGE code (Commercial and Government Entity Code), a unique five-digit number unique identifier assigned to suppliers to various government or defence agencies. These codes, which can be found through an online database of US Department of Defense’s Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), have been used to trace the origin of EO in Syria and Yemen.

Due to the enormous variety of EO models that exist, there is no centralised resource for identifying the meaning of labels and markings, even if they are clearly printed on the object. However, there are various guides that focus on specific types of EO, or those of certain origins. For example, the Collaborative ORDnance data repository (CORD) has a database of over 5,000 entries related to identifying landmines and other EO. Another example is Bomb Techs Without Border’s Basic Identification Guide to Ammunition in Ukraine, which covers every known item of ordnance used in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- Colours

The colour of the item of EO can also help identify its type and model. Different colours often represent the type of explosive within the item but can also designate their use cases, such as practice or training rounds, which are marked with a blue background and white writing by NATO nations.

Non-profit GlobalSecurity.org has a list of colour codes used by the former Soviet Union, the US and other NATO countries. There is also a useful guide to how to identify bullets – including explosive rounds – by the colour-coded markings on their tips here.

- Shape, size and other unique features

If the item has no immediately identifying marks, label, stamps, or colouring, the next step is to look at its shape and size.

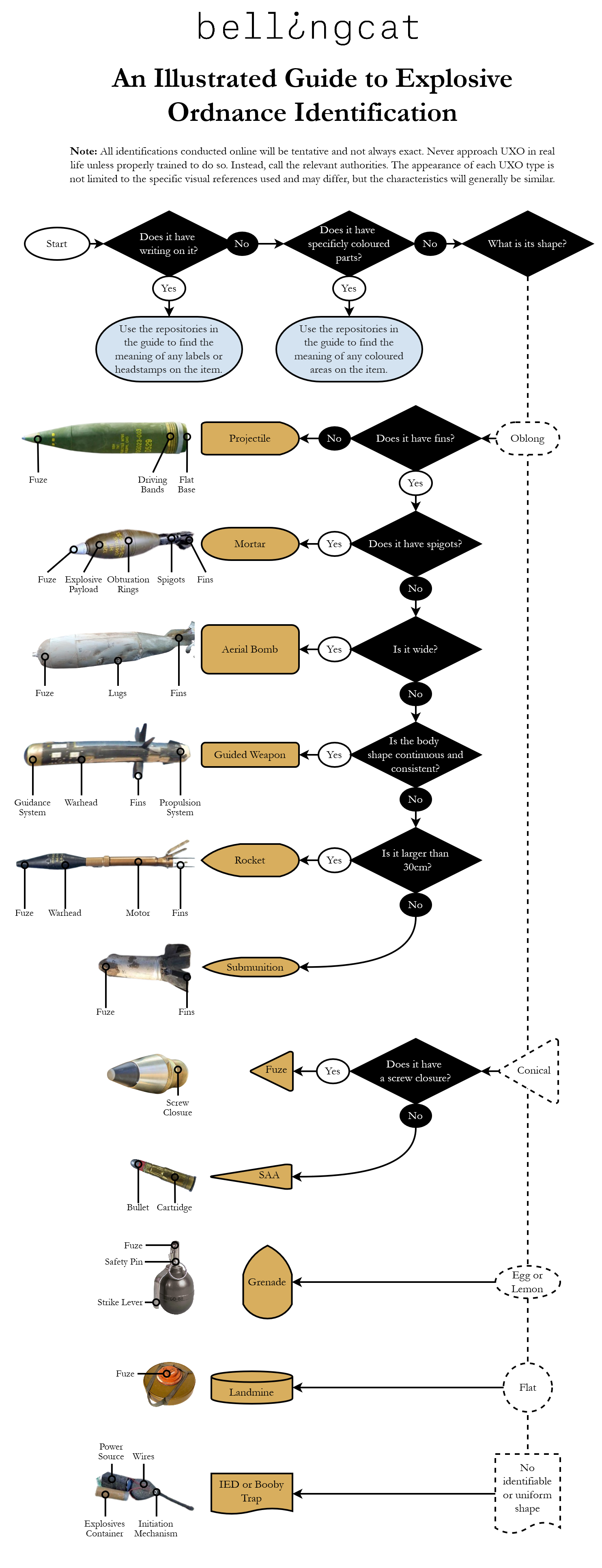

You may refer to the below slideshow for definitions of the types of EO mentioned previously, their common shapes and example images.

The descriptions are by no means exhaustive and only represent a summary of the most common models in each category. EO comes in all shapes, sizes, and forms. The decision tree below can also aid in the identification process.

Depending on the quality of and additional context in the imagery, it can sometimes be possible to measure the object’s approximate dimensions. Some of the tools and techniques you can use to do this are explained in this guide.

Contextual clues

If the the type or model of the EO shown in an image is still ambiguous, there are several clues that can help to further narrow down the scope of research and provide useful context.

- Location

Certain types of weapons are used in a limited number of locations. Geolocating where the image was taken can therefore help researchers identify the type of EO.

For example, Russia has not conducted any significant ground operations in its invasion in the Western part of Ukraine. Imagery from the far West of Ukraine, therefore, is more likely to show mostly advanced weapons deployed from the air, such as long-range cruise missiles or aerial bombs.

Cluster munitions, which disperse multiple explosive submunitions or bomblets over a wide area, are known to have been used in 41 countries and five territories since the end of World War II. Such munitions are banned under an international treaty signed by more than 100 countries due to the indiscriminate danger they pose to civilians, which helps narrow down the possible countries of origin for such weapons.

To learn more about geolocating imagery, refer to our previous guides here and here.

- Timing

The timing of the incident can be quite important too.

For example, if an event in Ukraine occurred prior to 2016, it is less unlikely to be of Western origin, as the Ukrainian Armed Forces received little Western support prior to 2016.

The timing is also important as it can give us a specific cut-off time to look for arms transfers that happened prior to the event. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute or SIPRI, provides an open database of all transfers of major conventional arms from 1950 to the most recent full calendar year, so identifying the time that the object was found can narrow down the range of EO that could possibly be shown in the imagery.

Similarly, some weapon systems can be discounted if the imagery is dated prior to a certain year due to the known development and deployment dates of some systems. For example, the PTKM-1R, a new Russian landmine, was shown publicly first in 2021 and used for the first time in Ukraine the following year. Thus, if the imagery is from before these years, it is highly unlikely to be this specific model. However, a small likelihood remains that a weapon could be used before it is publicly presented.

Investigators use various techniques to determine when a photo or video was taken, in a process known as “chronolocation”. These might include observing the length of shadows, or comparing satellite imagery from different dates to see if landmarks visible in the images have changed over time. Bellingcat has outlined some of these techniques in a previous guide on chronolocation.

- Other objects

Social media images or videos rarely focus on one specific object. If there are multiple objects in the target imagery, these can sometimes also act as clues to identifying the EO.

There will often also be other objects related to the EO shown around it in images, such as shell casings, fuses, shrapnel, ammunition boxes or machinery. These can help identify the type and model of EO. In many instances, the boxes used to carry the ordnance will have identifying marks. Landmines will often have safety caps made of plastic that are removed before emplacement. These will often be left nearby, thus serving as a potential clue.

Example identification process

Having outlined some of the techniques you can use to identify EO in social media images, let’s walk through a practical example following some of the steps above.

Below is a screenshot of a social media post reportedly showing an EO item in the Budennovsky district of Donetsk, Eastern Ukraine. This was found on the popular Типичный Донецк channel on Russian social media site VKontakte, which frequently reports on fighting in the area.

- Does the object have any writing on it? The answer is no. The item looks degraded and rusted, and unfortunately any identifying marks are either on the side in the earth or have eroded due to use or the weather.

- What colours feature on the item? The object is a light green colour but also heavily rusted towards the right of the image. Given the degraded state of the object it is difficult to identify its original colour and any colouring bands that might have been present.

- What is the object’s shape and size? Does it have any unique features? The object is oblong in shape with easily recognisable fins and spigots towards the left side of the object. It has circular marks on the right of the widest part of the body which are also recognisable as obturating rings – used to seal gases in for artillery – despite the heavy rusting.

Referring to our decision tree, we can identify it as a type of mortar ammunition. This can be confirmed by a check on the Open Source Munitions Portal with a search for other confirmed images of mortars. However, we are unable to narrow this down to a specific model without additional sources, as the object shown is highly corroded and there is no visible stamping or writing.

Other tools and resources

This guide has focused on identifying types of explosive ordnance in imagery originating on social media. However, given the complexity of and huge variance in types of EO, it may be necessary to refer to specific resources to identify them. We have collected some of the most helpful ones in a repository.

The repository is a living document with new resources added once updated or made public. Each resource is tagged by the category and origins or location of use of the munitions it covers. A brief description for each is provided as well. Most are free and open-access, although a small number require registration or have paid options.

Beyond human identification of objects in imagery, computer vision and machine learning are slowly being integrated into the EO recognition process. While development is still ongoing, several start-ups – VFRAME and Tech4Tracing – are working on this, which could make it easier for investigators to recognise objects not only in social media imagery, but also in live drone imagery in the near future.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here and Mastodon here.