How (Not) To Report On Russian Disinformation

Whether you’re listening to NPR, watching MSNBC, or reading the New York Times, you will likely be barraged with stories about Russian trolls meddling in every topic imaginable. No matter how obscure, it always seems like these nebulous groups of “Russian trolls” are spreading discord about the topic du jour — Colin Kaepernick, the Parkland shootings, and even Star Wars: The Last Jedi. But when we talk about Russian disinformation, what is actually happening, and how should the subject be handled with accuracy and nuance?

To be sure, there is such a thing as Russian disinformation, and it warrants coverage from journalists and researchers. However, the way that this topic is covered in many large Western outlets is not always as precise as it could be, and often lacks sufficient context and nuance. This issue came into focus this week when the New York Times published an article with a glaring inaccuracy about Russian disinformation — an article which was then shared by President Obama.

Democracy depends on an informed citizenry and social cohesion. Here’s a look at how misinformation can spread through social media, and why it can hurt our ability to respond to crises. https://t.co/qnLcR3mh8A

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) April 15, 2020

This guide will, hopefully, provide some general guidelines on how Russian disinformation, trolls, bots, and other subjects in this thematic neighborhood can be described without crossing into hyperbole.

The Low-Hanging Fruit

Following the Brexit referendum and the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Russian disinformation has been a hot topic for Western media outlets, think tanks, and investigative groups. There has been a huge demand for information on how mysterious Russian trolls and hackers work, but the output on these subjects too often reverts to hollow cliches and, ironically, misinformation.

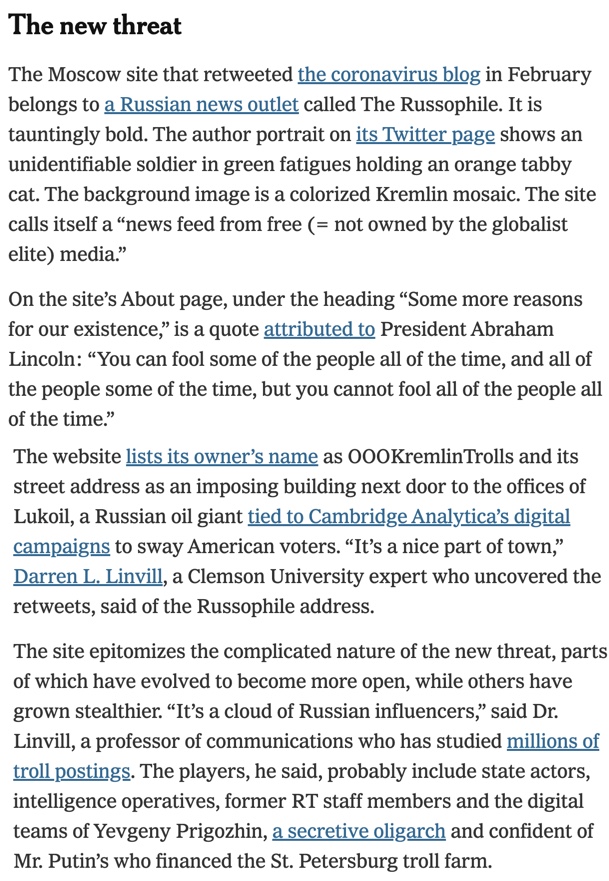

Even the most high-profile media organizations publish pieces on Russian disinformation that can be misleading or entirely incorrect. On April 13, 2020, the New York Times published a lengthy piece titled “Putin’s Long War Against American Science”, detailing the recent history of Russia and the Soviet Union in spreading disinformation about disease and health issues in the United States. One of the key moments in the piece, a screenshot of which can be seen below, describes how a site called The Russophile shared information about a coronavirus conspiracy theory. The Russophile is presented as a shadowy disinformation site with ties to the Russian energy giant Lukoil and Cambridge Analytica.

Unfortunately, the New York Times’ treatment of The Russophile is a concise case study in exactly what not to do in covering disinformation. To start with, to say that therussophile.org is an inconsequential website is an understatement. The eponymous Russophile is a long-time Swedish blogger named Karl with a little bit over 5,000 Twitter followers, and his site, as cited by the Times (therussophile.org), operates as a small news aggregator. Here, the most well-known newspaper in the world directly names a rarely-visited news aggregator ran by an obscure Swedish blogger mostly known to the English-language Russia watcher blog scene from a decade ago.

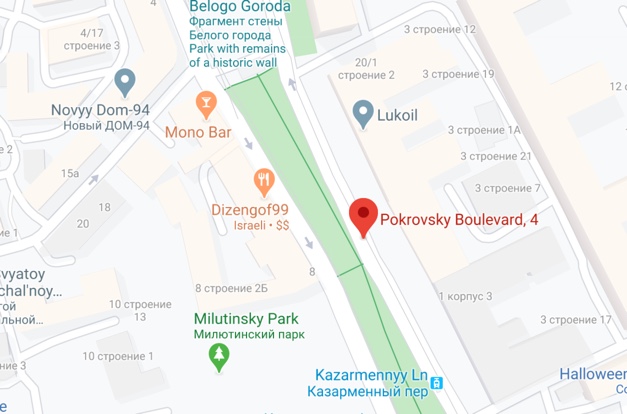

The blunder around the Russophile citation gets worse with the specific information raised regarding the “location” of The Russophile. On his site, he lists “Pokrovsky 4” in Moscow as his address, which the Times notes is ominously located “next door to the offices of Lukoil”, the massive Russian energy firm.

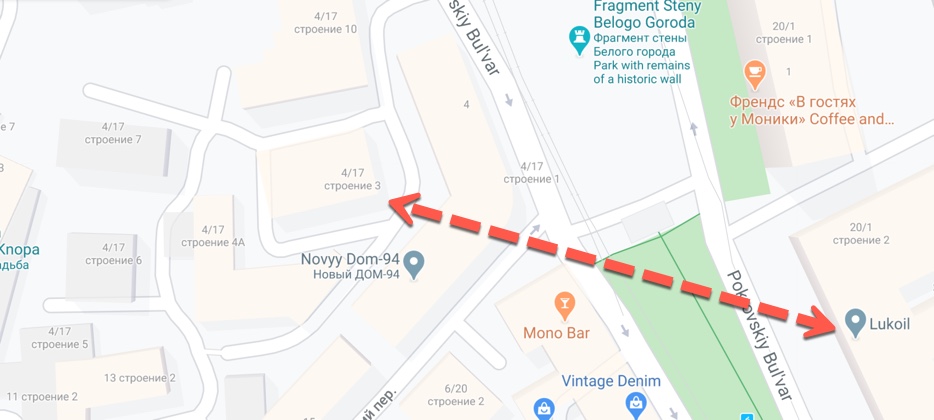

This claim is flatly wrong. Besides the fact that it’s very likely that this address was arbitrarily chosen (therussophile.org is, the best we can tell, a shoddily-made aggregator with a staff of one man), Pokrovsky 4 is not actually “next door to the offices of Lukoil”. The New York Times author (and fact checkers, and editor) likely plugged in the address into Google Maps — which does, indeed, put you next door to some Lukoil offices at Pokrovsky 3. If The Russophile had Lukoil in mind when assigning this address, he did a bad job, as this building is not the actual headquarters or close to the main office of Lukoil; rather, it is just the Stock & Consulting Center for the energy giant.

However, this address is not correct as there is no Pokrovsky 4 in Moscow. Rather, there are a number of buildings with the address of Pokrovsky 4/17, indicating that the buildings are located on an intersection between house numbers 4 on Pokrovsky and 17 on an intersecting street. The reason why Google Maps placed the (non-existent) Pokrovsky 4 there is because it estimated the location to be next to Pokrovsky 3, where the Lukoil office is located. Furthermore, on this boulevard, even-numbered houses are located on the west end, and odd-numbered on the east, meaning that Pokrovsky 4 would be, as Pokrovsky 4/17 is, located across the street from — and not next door to — the Lukoil office.

The mistakes that this report made are the direct results of reaching for the low-hanging fruit of disinformation reporting. The Russophile regularly shares blatantly untrue stories via his aggregation site, and listed a (likely arbitrary or fake) address in central Moscow, which the New York Times took at face value, which in turn led to further absurd assumptions of a relationship with Lukoil and even, implicitly, Cambridge Analytica. The real story of The Russophile is far more mundane, but does not make for an interesting narrative for print.

Russian Trolls, Bots, and Jerks

Much like the rise of the term “fake news”, the “troll” and the “bot” are now watered-down concepts divorced from their original intent. Just run a search of “You’re a Russian bot” on Twitter and you’ll see that, for many, it’s a go-to insult for when they disagree with someone.

Bots

Though the meaning of the word has shifted dramatically over the past few years, technically the term bot, as it relates to social networks, is an automated or non-human operated account. Many of these bots are useful, such as a bot that automatically tweets out the Twitter actions taken by Trump administration officials or a bot that will note whenever a New York Times headline has been modified, or meant to be entertaining, or useless, such as an account that randomly tweets out lines from Moby Dick or the Big Ben bot that tweets out bongs every hour. However, malicious bots also exist, and usually operate under one or a combination of three umbrellas: commercial advertising, political activity, or personal promotion.

Commercial bot nets are the most common of the three malicious categories, and are multi-purpose accounts that are sold to customers either temporarily or permanently. These bots will be deployed by a single user or firm to advertise a product or service — most often, spamming the link to a cell phone app, online casino, a bitcoin scam, and so on. In turn, these accounts are similar to spam email: they have a small success rate and rely on massive quantity, not quality, of messaging.

Another common bot deployment is for personal promotion, specifically in artificially boosting the popularity of an individual or group. A number of C-list celebrities, such as reality TV stars, purchased tens of thousands of follower Twitter bots, as revealed in a New York Times investigation, in order to boost the public perception of their popularity. However, just because a bot follows a person does not mean that they purchased this bot — most major figures have bot followers, so that the bot will seem more legitimate by following popular accounts and not just their client.

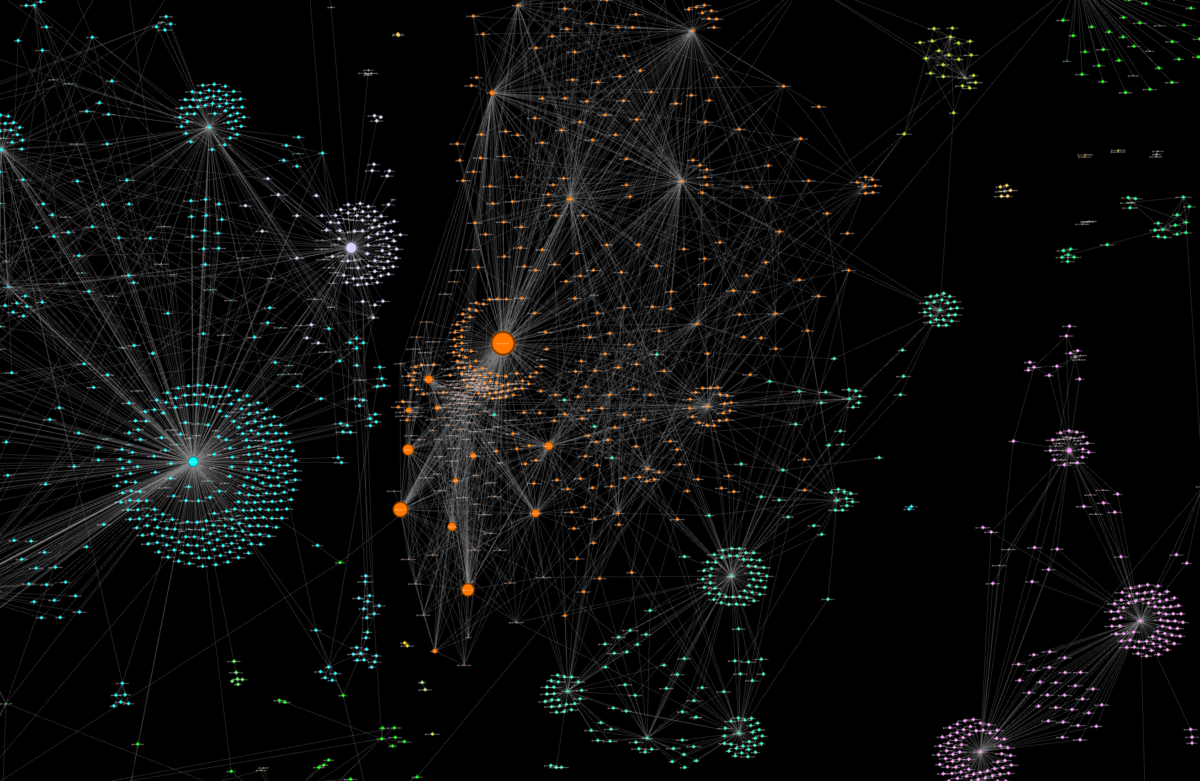

Last, and most nefarious of all, are the politically-focused bots. Most often, these accounts overlap with commercial bots, as a bot may be advertising a shady online pharmacy in Thailand one day, a Caribbean sports gambling site the next, and then sharing a hashtag promoting a specific politician or political party in India later that week. These botnets are often weaponized in some political goal, such as trying to artificially inflate the engagement of a specific hashtag or topic or to harass political opponents.

So, when is a Russian bot really a Russian bot? Most of the time, you can tell at first or second glance — a nondescript account sending out tweets out a bizarre rate and with a strange name. Ben Nimmo’s botspot guide is the most concise guide out there for identifying a bot, but in short: a Russian bot is an automated account that is working on behalf of a Russian entity or individual. A human person who disagrees with you is not a Russian bot, but rather (at worst) a jerk or troll.

Russian bots do exist, just as Indonesian bots and Israeli bots do. Specifically, they have been used by the infamous St. Petersburg Troll Factory (Internet Research Agency) and other Russian firms to spread links and juice engagements for hashtags. However, unless you can point to specific evidence that an account is automated or shows signs of being automated, hold off on the bot accusation, as the account may be a real person with feelings (and, depending on the severity of your accusation, a lawyer).

Trolls

Much like “Russian bots”, the “Russian troll” certainly exists online, but the term is a lot trickier to pin down than the relatively black-and-white definition of a bot. Most often, if someone is a jerk to you online or says something nice about Putin, they are doing it for free. However, a small minority of these people may be paid trolls working on behalf of a government or organization.

Many countries, just like Russia, pay (either directly or via friendly organizations/firms) actual humans to run accounts that promote a certain viewpoint or else are jerks to other people on social media. In China, they include the infamous 50 Cent Party. In Saudi Arabia, they are commanded by a number of high-ranking officials. In Azerbaijan, they threaten dissident journalists and their families. The Russian troll, in the context of an inauthentic user, is paid by the state (such as via the Moscow Mayor’s Office) either directly or through a friendly firm (the pro-Kremlin Internet Research Agency).

So, how do you know if someone is an unpaid Russian troll (also classified as a jerk, or someone who simply disagrees with you), or a paid one? The simple answer is that you probably don’t.

In 2013-4, back in the early days of the Internet Research Agency, identifying coordinated troll campaigns was relatively easy because of very sloppy account creation patterns and formulaic content, such as writing blog posts that were at an exact 250-word limit to quickly meet quotas. Now, trolls and paid / inauthentic content producers are a bit more sophisticated. A recent report from the Stanford Internet Observatory documented how a Russian state-sponsored operation created a number of faux experts focusing on a range of geopolitical topics who were published in alternative news outlets, such as GlobalResearch.ca. Notably, Counterpunch published their own internal investigation when they realized that one of these personas, “Alice Donovan”, had published articles on their site.

While there are certainly paid Russian trolls lingering on comment sections and on Twitter, most of these accounts are harmless. The more important accounts are state-sponsored accounts that appear to be independent analysts, grassroots organizations, and so on — and it isn’t easy to find these with the naked eye, as I experienced when I inaccurately assessed the @TEN_GOP Twitter account that was later revealed to be an inauthentic, Russian-made account masquerading as an American conservative. Instead, look for fairly concrete indicators that an account is not ran by an authentic person, such as fabricated CV details, a stolen avatar, or registration details consistent with an inauthentic account, such as an account using a phone number country code during registration that is not consistent with the user’s biography.

Cyborgs and coordinated campaigns

A brief addendum to this section to discuss a grey area to troll and bot identification methodologies: accounts that are partly automated, or engage in or coordinate human-led campaigns.

When assessing if an account is a (Russian or otherwise) troll or bot, keep in mind that many accounts can be classified as cyborgs — that is, with some content that is shared with automated scripts, and some content that is normal, human input. One of the more famous examples of this is Microchip, a pro-Trump Twitter user who runs countless bot and cyborg attempts, using both his own tweets that are written under normal conditions, and also automated, scheduled tweets that can be classified as inauthentic activity for political gain.

Lastly on this topic, keep in mind that “real” Twitter and Facebook users may appear to be state-sponsored trolls or bots, but are actually involved in a coordinated campaign. Hundreds of users have tweeted out identical messages that use the #USAEnemyofPeace hashtag — however, only a minority of these accounts are automated or could be classified as trolls. In reality, these accounts are copy/pasting templates that are provided by a coordinated Google site to spread particular links and messages, such as a Bellingcat article on American arms sales to the Saudi-led Coalition conducting airstrikes against Yemen. While this could be a state-sponsored campaign, the accounts copy/pasting these messages are, by and large, authentic and can’t be classified as bots or trolls, or even cyborgs for that matter.

The Reach of the Kremlin

While it is easy to imagine that every word that is printed in Russian newspapers is personally reviewed by Putin and a small army at Roskomnadzor, similar to Stalin proofreading articles in Pravda with a pencil before they went to publication, the media landscape in Russia is far from homogenous.

A common mistake of disinformation reporting is to ascribe pro-Kremlin or Russian nationalist outlets to being the views of the Kremlin. One disinformation analyst, for example, incorrectly described a historian’s article in the Russian newspaper Nezavisimaya Gazeta (“Independent Newspaper”) as official Russian nuclear doctrine. While the Kremlin does hold a strong arm over Russian media and has routinely silenced dissident outlets, there is plenty of autonomy among newspapers and websites (but not so much televised news). A brief and incomplete breakdown of these divisions is listed below:

State media involves a number of major outlets that are directly and explicitly owned by the Russian government, including RIA Novosti, RT, Rossiya-1 / Rossiya-24, and Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Functionally state media involves a number of entities that are not directly owned by the Russian state, but are owned by firms in which the state holds a majority stake, including the television channels NTV and Perviy Kanal / Channel One.

Independent, pro-government media are outlets that are not owned by the state or state-controlled entities, but are none the less favorable to the state in most circumstances. These include outlets like Izvestiya, Moskovsky Komsomolets, and Gazeta.ru. Often, the leadership of these outlets was replaced (directly or indirectly) by the Kremlin with less adversarial journalists, as we’ve seen with Lenta.ru and RBC.

Independent media not always favorable to the state mostly includes opposition-friendly outlets in the center and left, along with independent and business-focused outlets without a strong anti-government or pro-opposition bend, including Novaya Gazeta, TV Rain, Meduza, Ekho Moskvy, Vedomosti and Kommersant.

Fringe pro-government, Russian outlets often produce disinformation that is incorrectly ascribed as part of a Kremlin-coordinated campaign. While many of these sites, which include Tsargrad, Katehon, News-Front, and WarGonzo, have ties with the Kremlin or state figures, they are technically independent. The main challenge of analyzing these outlets is to determine the level of independence from the Kremlin; for example, RIA FAN is the “news outlet” ran by Yevgeny Prigozhin’s Petersburg Troll Factory and closely tied to the Wagner private military company. Though Wagner and RIA FAN are technically and legally independent entities, they are closely embedded with the state and often receive financial and logistical assistance, such as the Russian state expediting the issuance of foreign passports to Wagner mercenaries through their “VIP” passport office in Moscow.

Fringe non-Russian, pro-Russian outlets include places that have no direct (but perhaps indirect) institutional ties to Russia, but are nonetheless generally favorable to the Kremlin. These outlets include websites legally registered all over the world, such as The Duran, GlobalResearch.ca, and Infowars.

Correctly describing the media outlet producing disinformation is extremely important, and will prevent mistakes such as misattributing the actions of a Swedish man running a small pro-Kremlin aggregation site to the Russian state and a massive energy company headquartered in Moscow, as we saw with The Russophile.

Audience Matters (a lot)

Perhaps the most important lesson of addressing disinformation is to consider the importance and consequences of highlighting specific reports. Cherrypicking reports of disinformation is not terribly difficult — there are a bevy of “alternative news” sites that are ideologically driven and far from truthful in their publications. However, when a large media organization such as the New York Times lifts a little-read or obscure story, the tiny whimper of disinformation is transformed into something far louder and more dangerous.

As of the time of this piece’s publication, the tweet from the Russophile account sharing the coronavirus disinformation described in the New York Times had one retweet and two favorites. An engagement of three people is, apparently, enough to warrant a reaction in the paper of record.