Using Citizen Science to Assess Environmental Damage in the Syrian Conflict

For new and ongoing conflicts across the world, the need to document their impact on civilians and the environment upon which they depend is encouraging the development of new research tools and methodologies. Traditional approaches for monitoring environmental risks are notoriously reliant on field access for experts. But with civilians increasingly able to access the Internet and mobile networks, and with their growing use by warring parties, new opportunities are being created for the collection of environmental data, by experts and civilians alike.

By Andy Garrity (Toxic Remnants of War Project) and Wim Zwijnenburg (PAX)

Following on from the blog Online Identification of Conflict Related Environmental Damage, which focused on Syria, this blog briefly examines the potential for using citizen science tools in Syria to quantify the extent of environmental degradation. Could citizen science tools inform both efforts to reduce threats to public health from environmental risks, and longer term remediation plans?

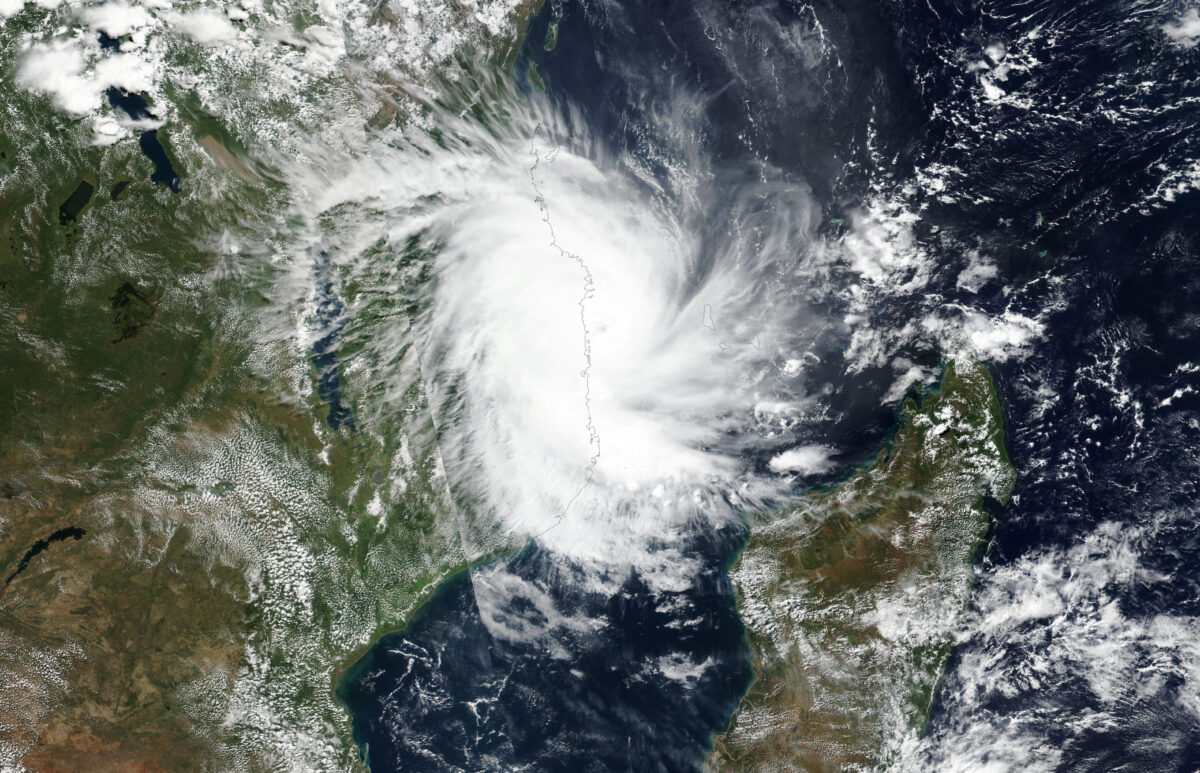

The conflict in Syria is entering its fifth year. It has resulted in widespread destruction to residential and industrial areas, critical infrastructure, the oil and gas industry and the total collapse of environmental governance in affected areas. Moreover, the hosting of refugees in neighbouring countries is placing a huge strain on national infrastructure, natural resources and biodiversity. What information there is available from within Syria indicates that the environmental impact of the fighting has resulted in toxic and hazardous hotspots, with acute and chronic risks to public health.

Citizen science

The rise of citizen science in the last four decades has opened up new opportunities for humanitarian and environmental organisations, with the range of hardware and software applications available steadily increasing. Citizen science can be defined as: “Scientific work undertaken by members of the general public, often in collaboration with or under the direction of professional scientists and scientific institutions,” and it has greatly contributed to broadening the participation of non-scientists in a range of scientific projects. So, could citizen science be used to identify and monitor environmental impacts in Syria and other conflicts, and what other benefits might arise from civilians participating in such projects?

Monitoring and assessing environmental impacts through citizen science in conflict and post-conflict settings could help overcome specific difficulties relating to the documentation of environmental hazards caused by conflict. Overall, environmental data collection during conflicts is often minimal, primarily because of the security constraints faced by external specialists. A further constraint is that of technical expertise and access to monitoring equipment. Where comprehensive environmental impact assessments (EIAs) are done, these may only be possible following the cessation of hostilities and the restoration of security. Political and funding constraints often mean that many conflicts are not thoroughly assessed in this way.

For conflicts where post-conflict EIAs are undertaken, data from citizen science initiatives could help broaden the temporal scope of the EIA, highlighting changes to environmental quality over time. They could also help direct those undertaking post-conflict assessments to environmental problems and, by increasing visibility and raising awareness of environmental threats during the conflict itself could help encourage the support of the international donors that fund formal EIAs.

Moreover, being able to contribute to analysing the conflict’s environmental impact on their community, and receive feedback and support, could prove a useful tool for risk education and in strengthening civilians’ sense of agency in such settings. In Syria’s case, civilian access to smartphones and the Internet is widespread, potentially providing opportunities for both civilians and humanitarian organisations to contribute to data collection efforts.

What tools are available?

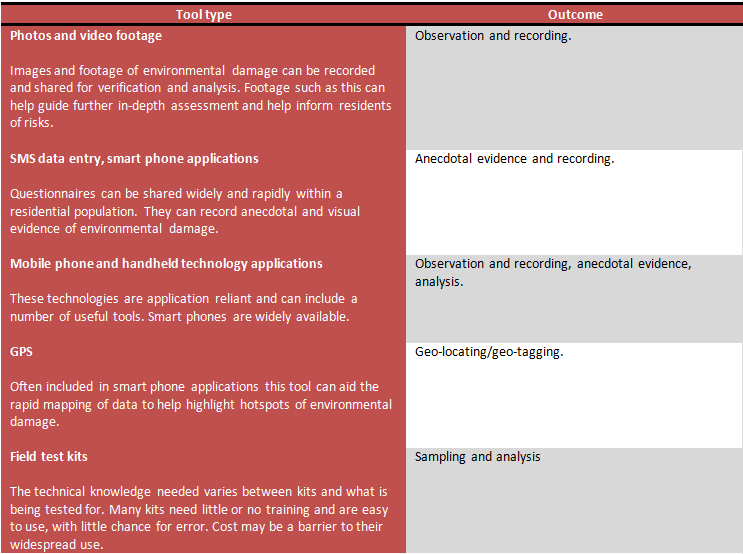

Different citizen science tools can provide different levels of scientific detail and accuracy. The more complex tools can help provide highly informative analytical outputs that help quantify problems. The more simple tools can produce less technical outputs but can nevertheless act as a stepping stone for more thorough scientific investigation.

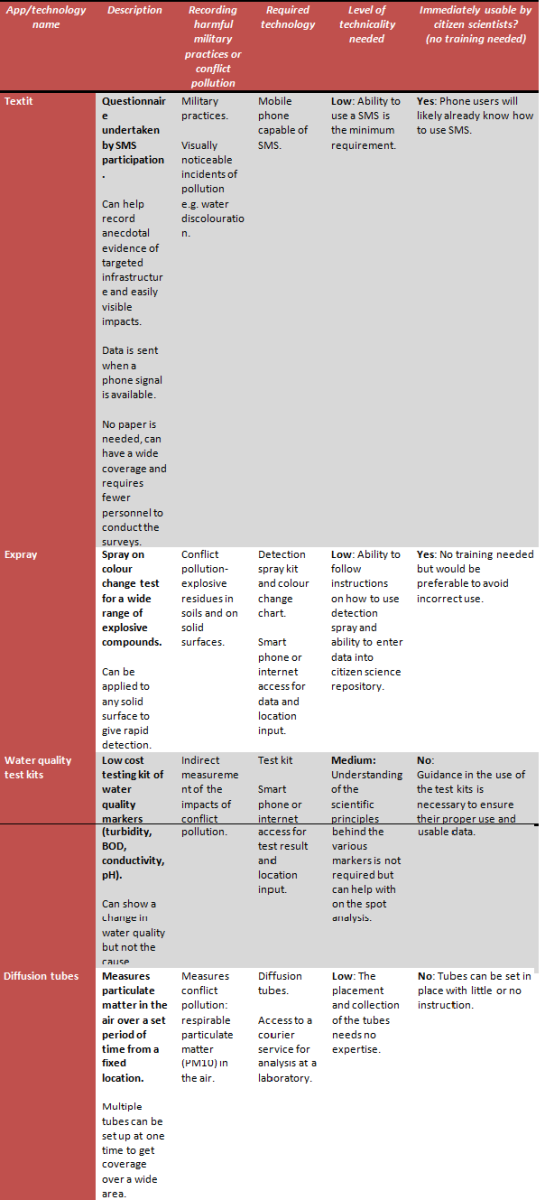

Table 1 lists a number of peacetime citizen science tools and their outcomes that could be applicable in Syria in order to record, asses and share data

Observation & recording

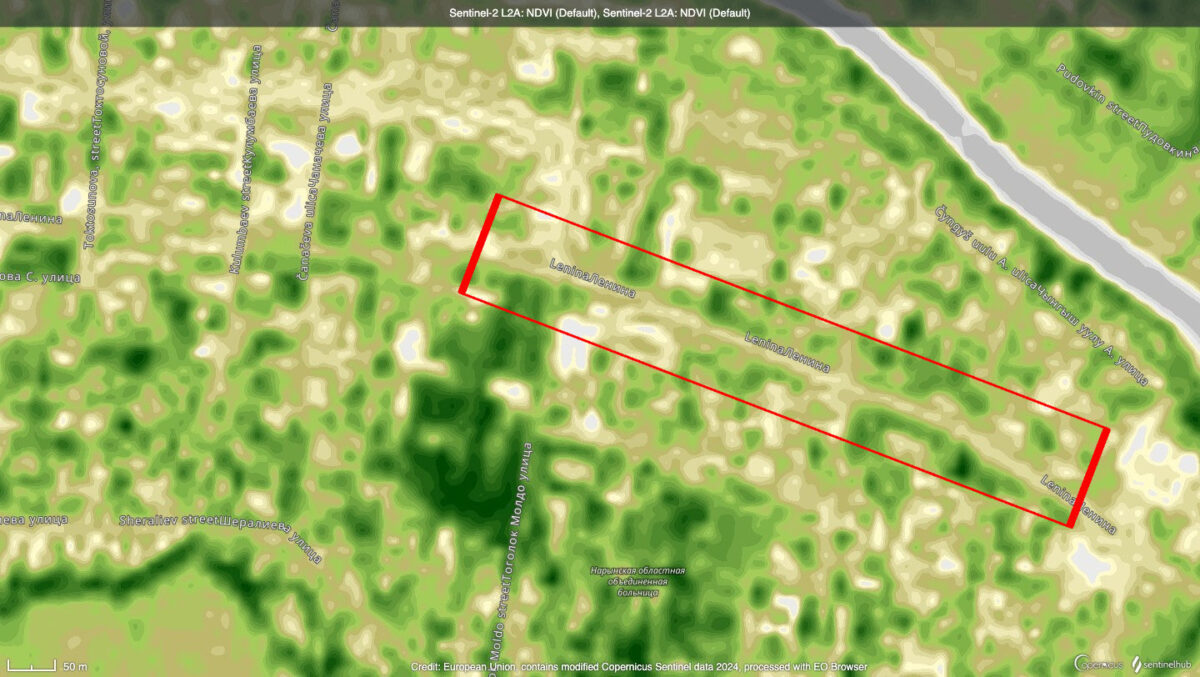

One of the least technical forms (requiring the least training) of citizen science is observation and recording, where visual changes to the environment are documented. In peacetime settings these are often easily identifiable environmental changes, such as the time of year colour change occurs in leaves or tree species. For recording toxic remnants of war (TRW) in Syria, this could be used for recording the presence of asbestos in conflict rubble, which is easily identifiable without the need for handling; the recording and geo-tagging of craters where artillery has fallen and could contain explosive residues as well as UXOs; or attacks on industrial sites where hazards substances are stored or processed.

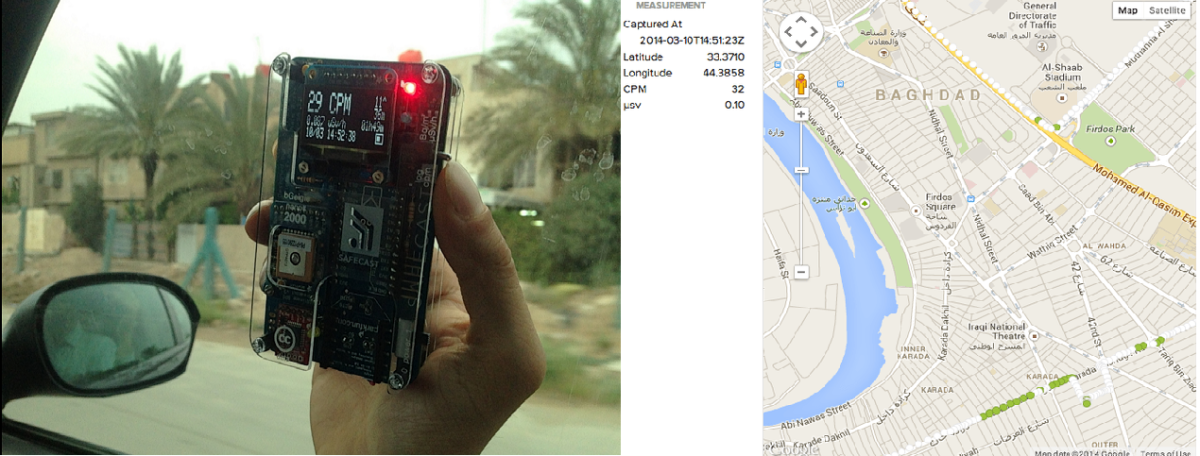

Safecast Open Data collection by monitoring radiation in Baghdad, Iraq, 2014

The data could be fed into a larger database or mapping system by social media, email or SMS, or via specially developed data input applications that are readily available to stakeholder groups. This would require a coordinated effort that includes UN specialists, humanitarian organisations, environmental experts and civil society to provide analysis and feedback to those participating in the project.

Observation and recording could simply be the retention of photographic evidence following the targeting of urban areas, which would provide an on the ground view for first responders and residents who may need advice on risk avoidance if certain forms of environmental contamination are present. It could also aid more long-term environmental clean-up programmes[i].

Anecdotal and visual evidence can be recorded electronically via SMS and smartphone applications. Programmes such as “Textit” allow a number of specific questions to be put to residents, and also provide advice based on the responses given. Mobile phones are widely available in Syria and can send data to the central database whenever there is a signal present, without relying on constant access to a mobile phone network. This could be beneficial in conflict zones where communication services can be intermittent. The incoming data would be useful as an initial assessment of the most prominent and widespread environmental problems in a given area and could help guide the use of further citizen science applications for more detailed assessment[ii].

Sampling and analysis

Some peacetime citizen science schemes involve the use of basic sampling techniques; these may require some instruction in how to use the low-cost apparatus. One example is the Air Monitoring Network in the UK. These uncomplicated technologies would be easily transferable to conflict and post-conflict settings, or even peacetime military settings such as domestic firing ranges. Tools for measuring contamination would be applicable in scenarios where there could be acute health hazards such as contaminated water resources, exposure to explosive or industrial substances and contamination in densely populated or agricultural areas.

Other common forms of conflict pollution may need a higher level of technical expertise and training. This is necessary to obtain laboratory acceptable samples for analysis to identify substances such as the heavy metals that are associated with the use of munitions (lead, mercury, copper, zinc, antimony, tin or arsenic) in built-up areas and which may be linked to chronic exposure illnesses such as cancers and kidney disease.

Table 2: Examples of sampling, analysis and data entry technologies for citizen science.

Providing information and resources

Smartphones and mobile phone networks can also provide a platform for informing civilians on safety and security issues. One example operating in Syria is the International Committee of the Red Cross’ (ICRC) GPS based map, which informs Aleppo’s citizens on where safe drinking water can be accessed. In another example, Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) initiated a website informing civilians of the dangers of unexploded ordnance (UXOs). Finally a project organised by Safecast sought to monitor radiation through open data collection in Iraq after the 2003 war. Though limited to those having a (smart)phone and internet access, these technologies build better streams of information that can help increase civilian protection by informing them of safe locations, resources and information on a range of hazards.

NPA Risk Education website on explosive remnants of war in Syria

Mutual benefits

Citizen science is very much about the participation of non-scientifically trained but concerned volunteers. Projects could allow Syrians to become involved in decision-making processes and give communities a voice in telling the world about how war impacts their livelihoods and health, helping to demand change in military practices and holding states and individuals to account.

Residents can learn scientific and analytical skills, gain more knowledge about their neighbourhoods and how to protect and preserve sensitive environments, while sharing their own knowledge with the rest of the world. There is a real potential to develop an understanding of environmental principles and the relationship between a healthy environment and good health, food security and clean drinking water, as well as promoting ideas of environmental peace building and co-operation.

Improved information awareness and exchange could also alleviate broader psycho-social concerns. Civilians are often left in the dark with regard to changes in their environment and potential exposures to a range of hazardous substances. General concerns over wellbeing can also result in psycho-social impacts, when ill-defined environmental risks are attributed to health problems, which can results in a sense of helplessness and strengthen grievances. Providing clarity and information could help counter this. Information on specific environmental hazards could encourage behavioural changes that serve to minimise harm and in doing so help build stronger resilience mechanisms for conflict-affected communities, providing information resources to allow them to adapt to changes in their environment.

Limitations and additional risks

Undertaking citizen science in conflict and post-conflict zones carries with it risks and limitations that are not present in the peacetime settings for which many methodologies were developed. This requires particular care and attention in the training for, and conduct of, activities in these contexts. Some cases of contamination may involve substances with an extremely high level of toxicity, requiring personal protective equipment (PPE), and some background knowledge of how the substance behaves and potential exposure routes, in order to safely sample or assess its impact.

Asking citizen scientists to undertake high risk assessments in locations such as industrial sites can’t be justified so data on these sites may be limited to anecdotal and visual assessment. Locations of interest may also be littered with UXOs, again placing citizen scientists at unnecessary risk. There is also the risk of conducting any sampling or observation and recording in active conflict zones, where there is the real and immediate risk to life from weapons use.

There are also logistical issues to consider, such as delivering sampling kits and chemicals across borders and into conflict zones. Two of the principal aims of citizen science initiatives during conflict are to overcome the time delay between a conflict ending and impact assessment teams conducting environmental studies, as well as the overall lack of data collection. Restrictions on the movement of equipment and samples could therefore seriously hinder projects.

These problems could potentially be overcome by including test kits in humanitarian aid packages and promoting the use of DIY alternatives, such as the use of sticky tape to sample particulate matter instead of diffusion tubes.

Conclusion

Citizen science applications have not been widely used in post-conflict zones to record and quantify environmental damage and conflict pollution before now. Although the available technologies and methodologies have a solid track record in peacetime settings, such as in community-led air monitoring – and even in more extreme settings, such as in tracking the movement of poachers – it is still unclear if they could be successfully applied in conflict contexts.

Nevertheless, and in spite of the risks and imitations outlined above, the Toxic Remnants of War Project believes that these approaching are worth exploring and piloting. If successful, the use of citizen science would be extremely useful in documenting harm and giving communities a voice in sharing and tackling the risks they face to their livelihoods and health, long after the conflicts they have lived through are over.

Andy Garrity is a researcher with the Toxic Remnants of War Project, which studies the environmental and humanitarian risks from conflict and military pollution, @AndyTRW; @detoxconflict.

Wim Zwijnenburg is the project leader for humanitarian disarmament at PAX, a Dutch peace organization and works on conflict and environment related issues in the Middle East. @wammezz @Paxforpeace

References

[i] Some of these techniques have already been implemented in Syria under the guise of citizen journalism where human rights abuses have been recorded, verified and even mapped out during the ongoing conflict. A good independent example of this is the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

[ii] However questions relating to the secure transfer and storage of data would need to be resolved first in order to protect the identities of civilian participants.