Cleared for Takeoff: Exploring Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020's Research Potential

Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 (MFS2020) launched last week, promising players the ability to fly anywhere on the planet thanks to the integration of several technologies. The game pulls satellite images from Bing Maps, and populates them with objects (such as trees and buildings) using the Microsoft Azure cloud network. The game “knows” whether an object needs to be rendered using an artificial intelligence machine learning algorithm from Blackshark.ai.

The results are impressive, life-like visuals of anywhere on Earth, from cities and small towns to natural wonders and everything in between. The game’s ability to render objects and places is so impressive that it got us wondering — could we use this as a tool for open source investigations? Could the game’s AI-generated 3D models be so accurate to help with geolocation, and if not, could they serve another purpose?

Over the past few days, we’ve experimented with MFS2020 and visited cities big and small, conflict zones, and even areas of environmental concern to answer these questions. We found that while the game’s 3D models are not accurate enough to be reliable for geolocation, the way that the game renders topography, along with its dynamic lighting and weather capabilities, could help with background research by giving investigators a “feel” for the places which they are exploring.

AI World-Building (And Its Limitations)

The aspect of the game that first caught our attention was its ability to render 3D buildings: 1.5 billion spread across 2 million cities, according to Microsoft. Blackshark.ai has a description on its website which explains how its artificial intelligence algorithm detects and renders buildings from satellite imagery, no matter how remote the location. Google Earth Pro, for comparison, is an indispensable tool for geolocation because aside from providing users with high-resolution satellite imagery, it also renders topography. If MFS2020 could add to that by providing accurate building models from anywhere on the planet, then it could be useful for geolocation tasks.

After a few experimental flights, however, it became clear that while the AI did an impressive job at rendering cityscapes in general, it has some important limitations that make it unreliable as a tool for a task as precise as geolocation.

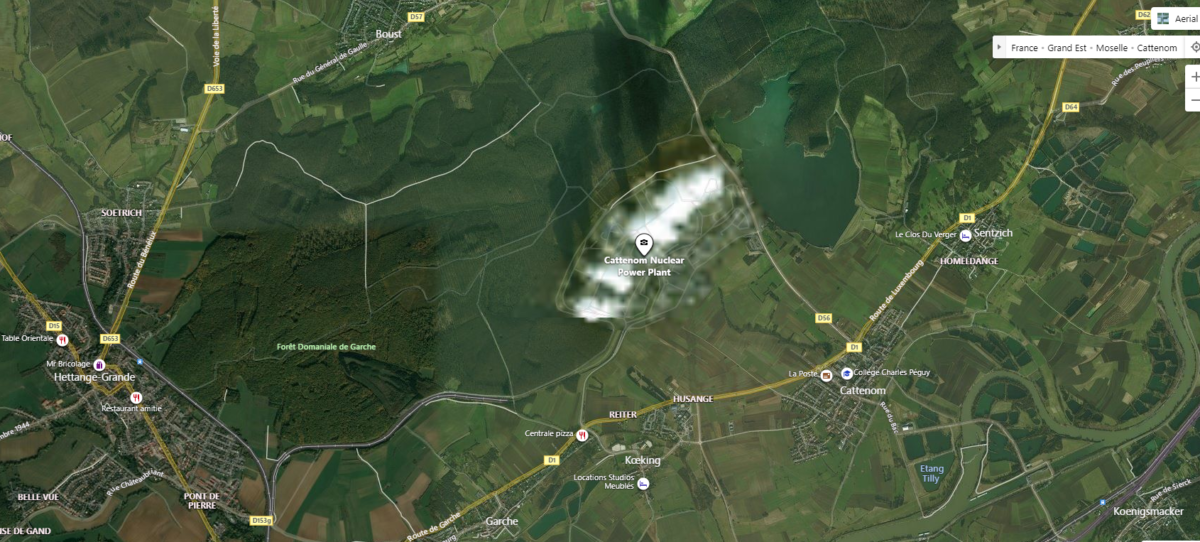

For example, the AI sometimes does not recognize structures and simply fails to render them at all (or puts them in incorrect places), as in the example below from this neighbourhood in Seoul, South Korea:

Left: A neighbourhood in Seoul, South Korea in MFS2020. Note that some of the buildings have failed to render, while others have been placed in the middle of roads. Right: The same neighbourhood in Bing Maps (Source: Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020/Bing Maps)

Even when the game recognizes a building and renders it, the result is sometimes inaccurate. For example, this location in the city of Maiquetia in Venezuela contains a number of buildings that were rendered to be incorrect heights, three of which are highlighted below (for another example of incorrect height rendering, check out this article from PC Gamer):

Left: Three residential towers as they appear in MFS2020. Right: The shadows in the Bing Map satellite image indicate that they are much taller than in the game (Source: Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020/Bing Maps)

This is also evident with unique structures like El Helicoide, a building located in Caracas that was envisioned as a state-of-the-art shopping mall in the 1950s but is now used as a jail for political prisoners. The game AI recognizes that there’s a building there and attempts to render it, but only manages to properly identify part of the structure:

The game recognized some of the building’s features and rendered them (Source: Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020)

Topography, Lighting, and Weather Effects

From what we’ve seen so far this week, the game handles topography really well, even beating Google Earth Pro (in our opinion) in a test comparison. This is because MFS2020 provides higher landscape fidelity than Google Earth Pro, including dynamic lighting, shadow, and atmospheric effects, creating more lifelike vistas. (Note: Google Maps incorporates some of these features to create more life-like vistas of the world than Google Earth Pro, including 3D buildings from many places in the world. We tend to use Google Earth Pro for tasks like geolocation more often, though, because the camera is easier to navigate and position, and because it offers more tools that are useful for our purposes including the ability to import/export KML files).

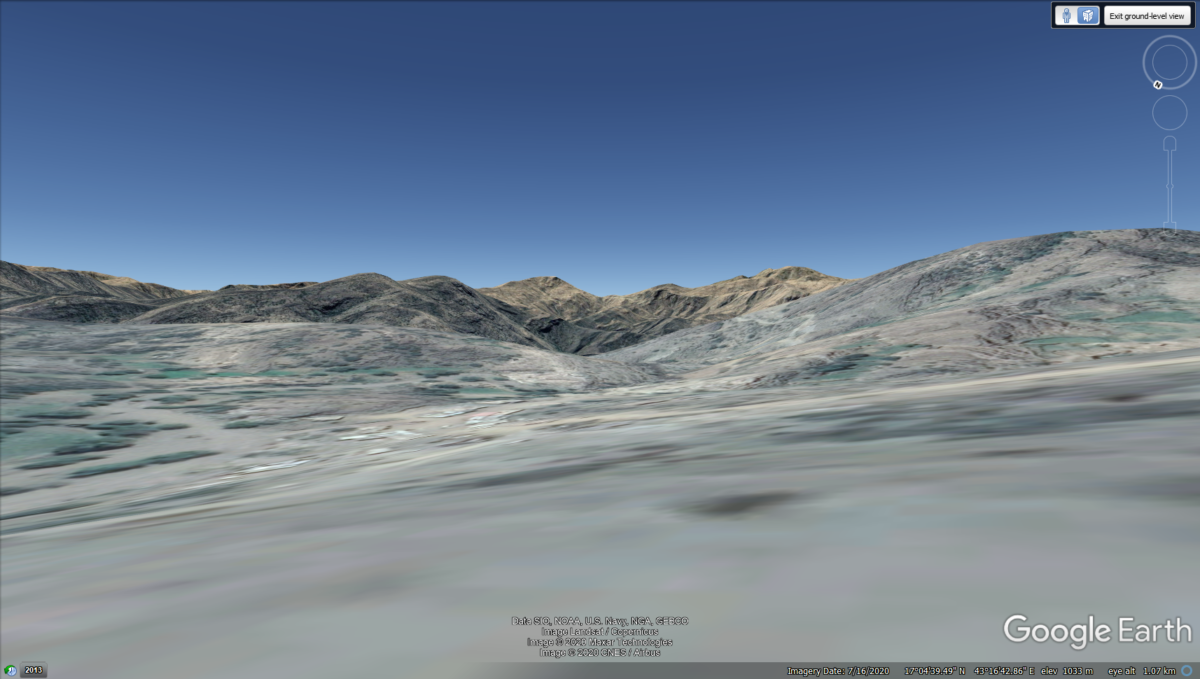

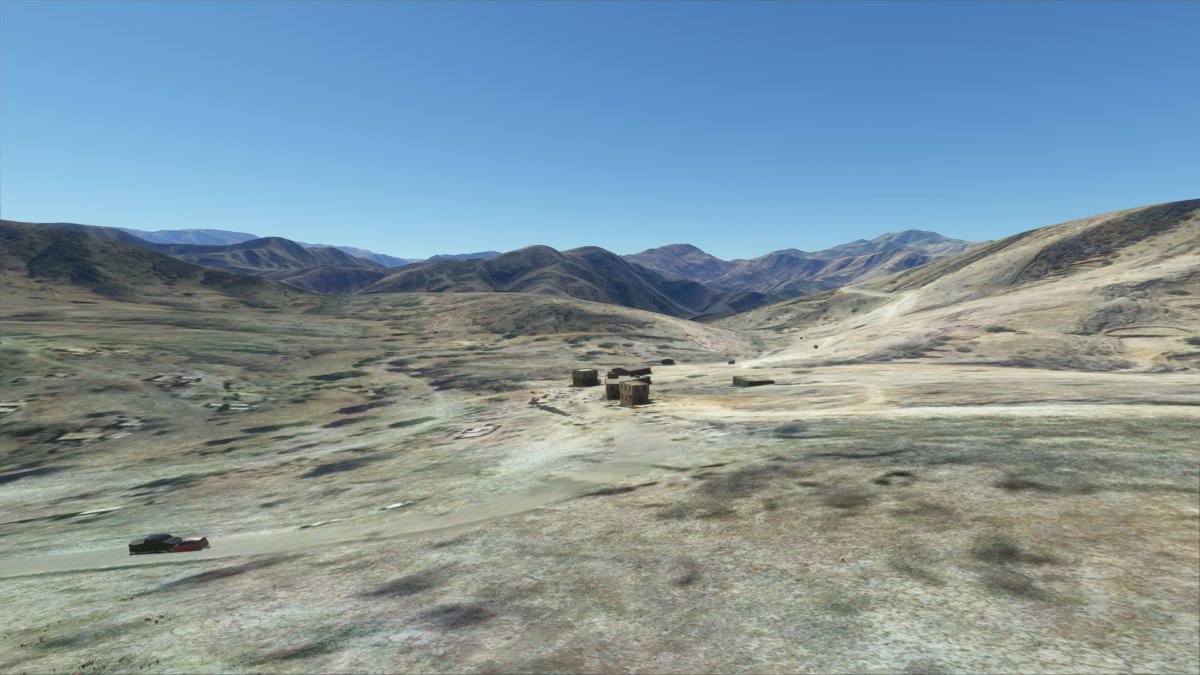

The images below were captured from the same location in western Yemen, which was the site of an airstrike by the Saudi-led Coalition in August 2015. The top image is the spot as it appears in Google Earth Pro, while the bottom image is from the same spot and viewpoint as it appears in MFS2020:

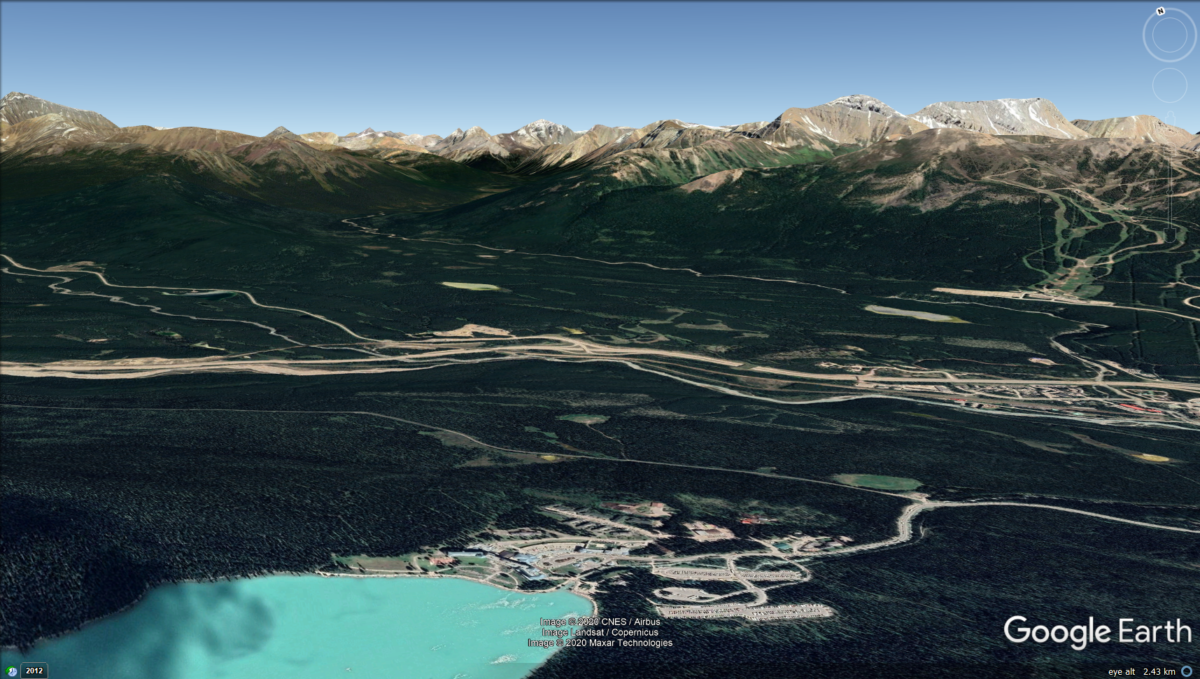

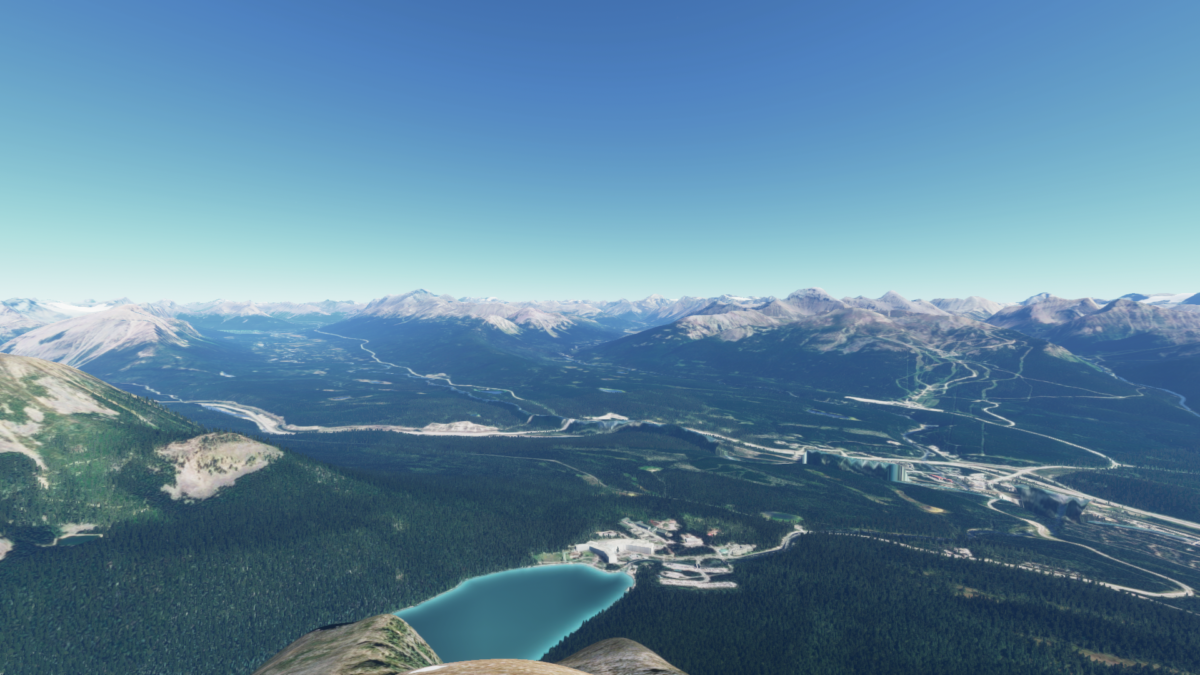

Similar results are evident in this vista, captured at Lake Louise, Alberta:

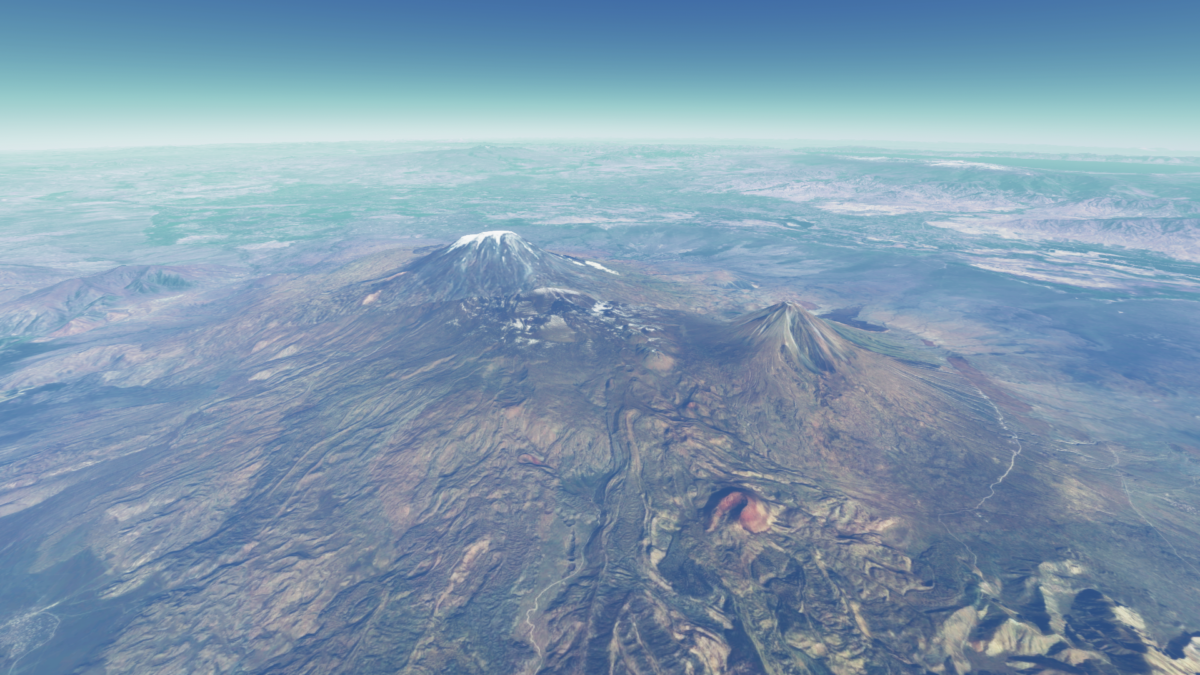

Below, you can see a three-shot comparison of Mt. Ararat from the Turkish side. The top image is the mountain as it appears in Google Earth Pro; the middle image is a photograph of the mountain, while the bottom image was captured in MFS2020.

The game also includes a dynamic weather and time system that allows players to change these settings while they’re in the game. Below is an example video of this feature captured in-game near the Alpamayo mountain in Peru:

Humanity’s Worst Aspects, Simulated

Just as the game can render beautiful natural vistas and captivating city skylines, it can also simulate locations associated with our worst aspects as a species. The virtual world of MFS2020 is filled with the models of the conflict zones and ecological catastrophes that we have created.

The image below shows the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Central Processing Centre, a detention facility in McAllen, Texas where the U.S. government detains undocumented migrants. The facility made headlines in 2018 when images surfaced in the media showing the deplorable conditions to which its inmates — in particular, children — were subjected.

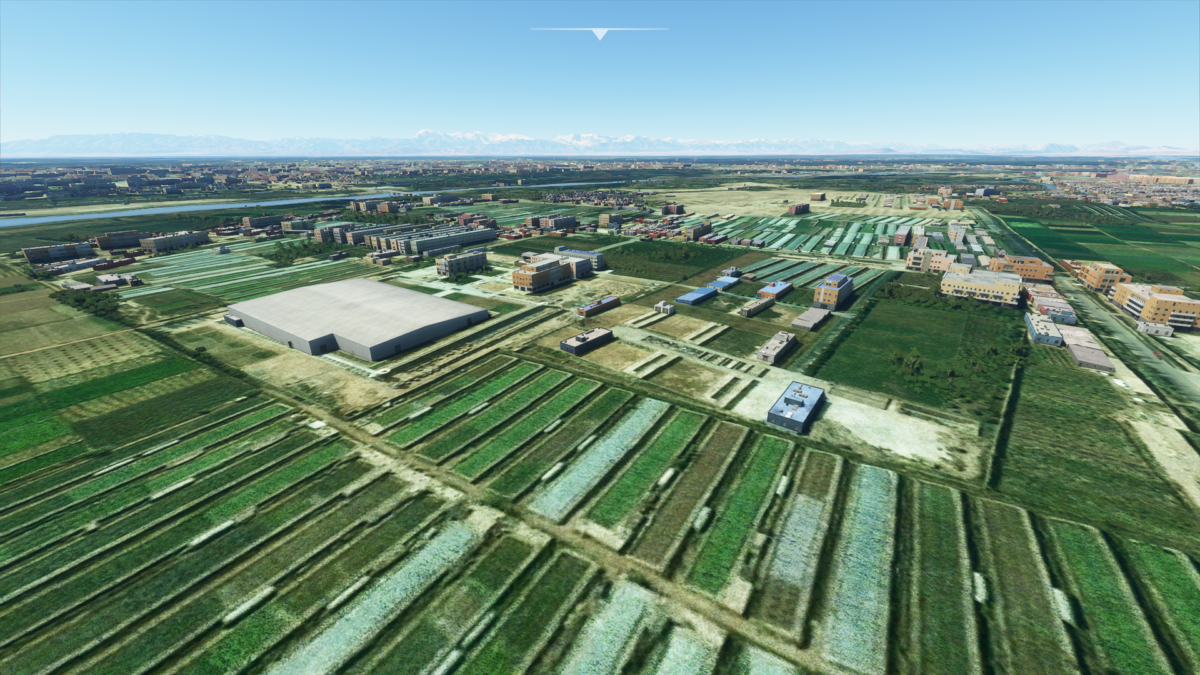

Using this database of Xinjiang re-education camps from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, we found the game’s version of a camp in the city of Kashgar (note the more recent image from Google Maps showing more buildings at the site):

In Ukraine, we found evidence of ongoing armed conflict in the form of craters near Savur-Mohyla:

The game also rendered some buildings near the Kuzminsky firing range, which is a Russian military base used as a staging area for troops (note the more recent image from Google Maps showing the base):

The Bing Maps satellite image of the Donetsk International Airport shows only light damage at the terminal (it is, in fact, completely destroyed as of today). Because of this, the game renders the airport as being fully functional, and even populates it with aircraft at the terminal, cars in the parking lot, and ground equipment vehicles on the apron:

A pristine, operational Donetsk International Airport in MFS2020. The real airport has been completely destroyed (Source: Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020)

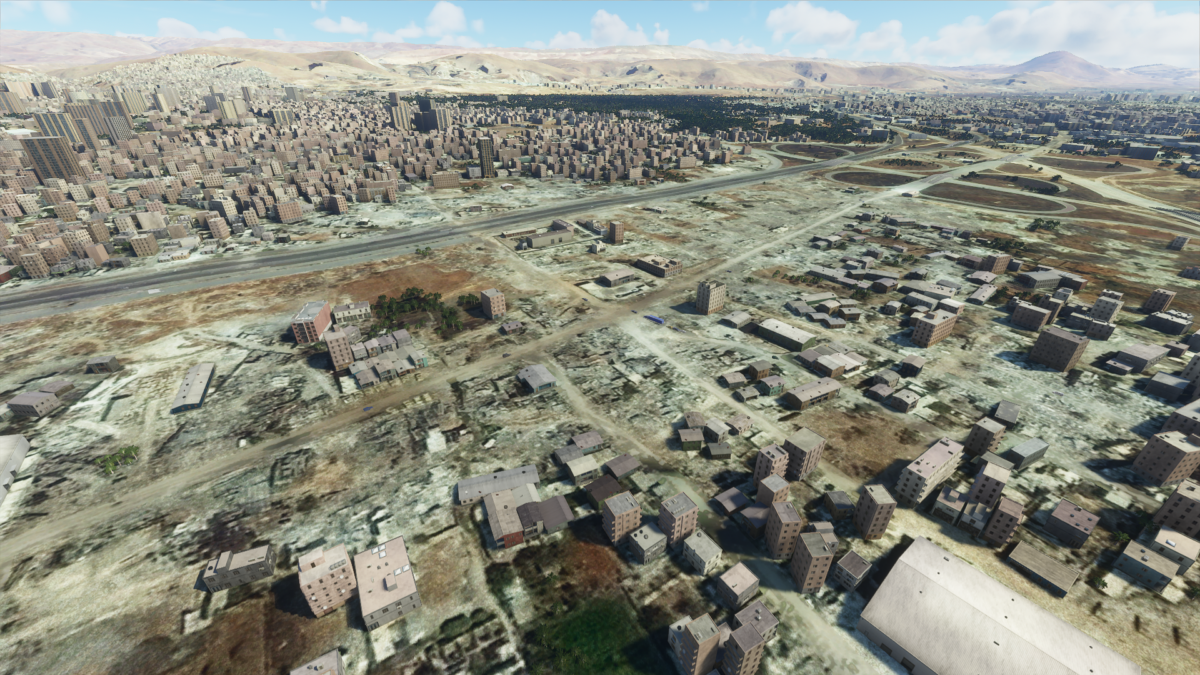

In this neighbourhood in northeast Damascus, you can see that the satellite image layer shows rubble from buildings that have been shelled. Wherever the game detected buildings that were still standing, it rendered them:

The game has rendered a few buildings that appear to be standing on the Bing Maps satellite image from this location in Damascus, Syria (Source: Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020)

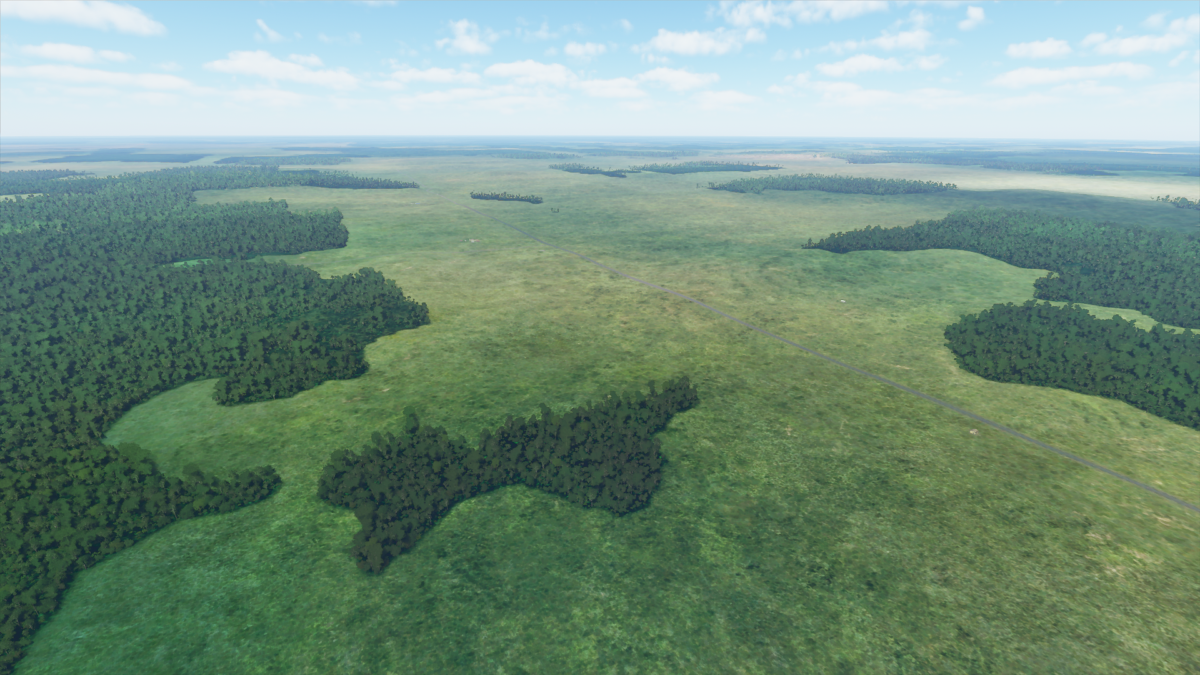

The game also renders trees. Below is a section of deforested Amazon jungle in Brazil, near the border with Bolivia:

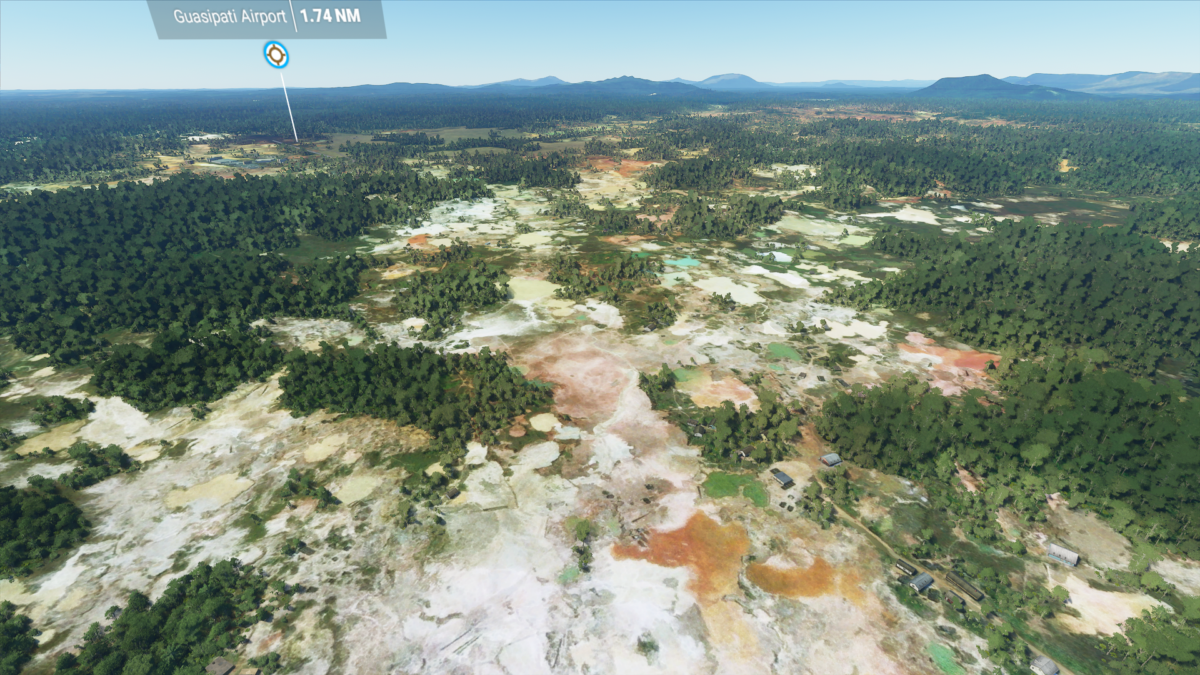

And, in Venezuela, the game’s rendering of the Las Claritas mine provides an upsetting look at the ecological damage being done to that area:

Future Research

Other avenues of research worth exploring with MFS2020 are its real-time weather and air traffic features. It would be interesting to explore how the game renders large thunderstorms or hurricanes, for example.

Because there are places in the world that appear pixelated in Bing Maps, we checked out a couple of them to see if they also appeared pixelated in the game (for a list of pixelated/unclear places in mapping services, check out this Wikipedia article). We found that the game still rendered some buildings in the two places that we checked, but it would be interesting to explore other sites to figure out how the game decides what to render and where.

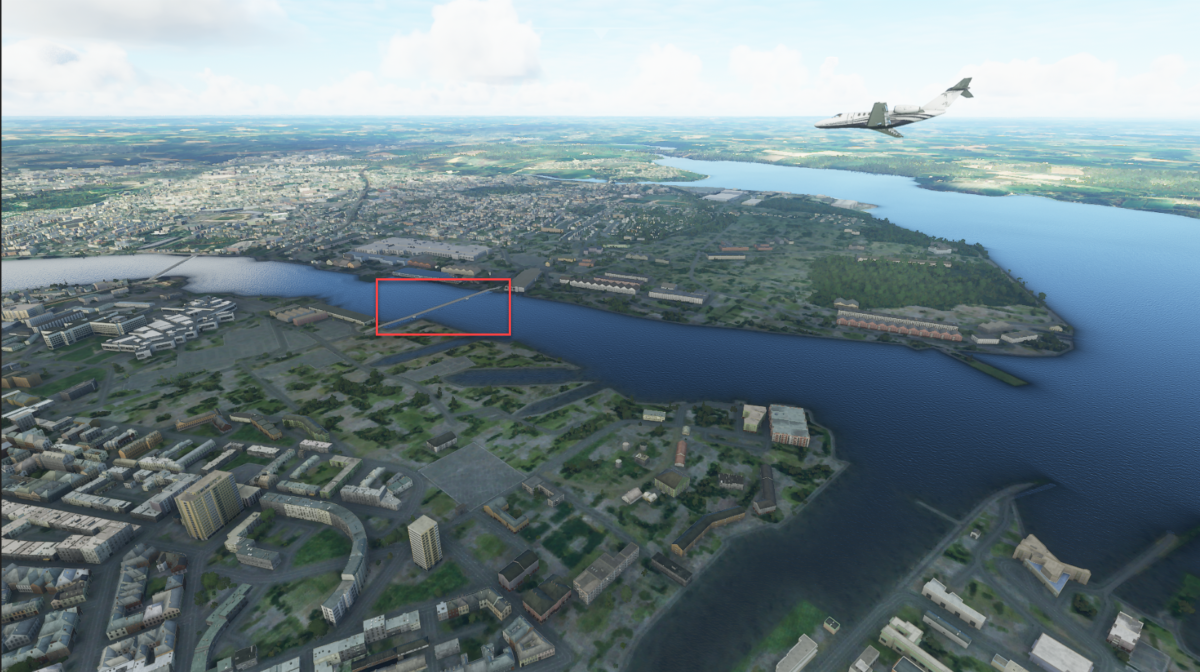

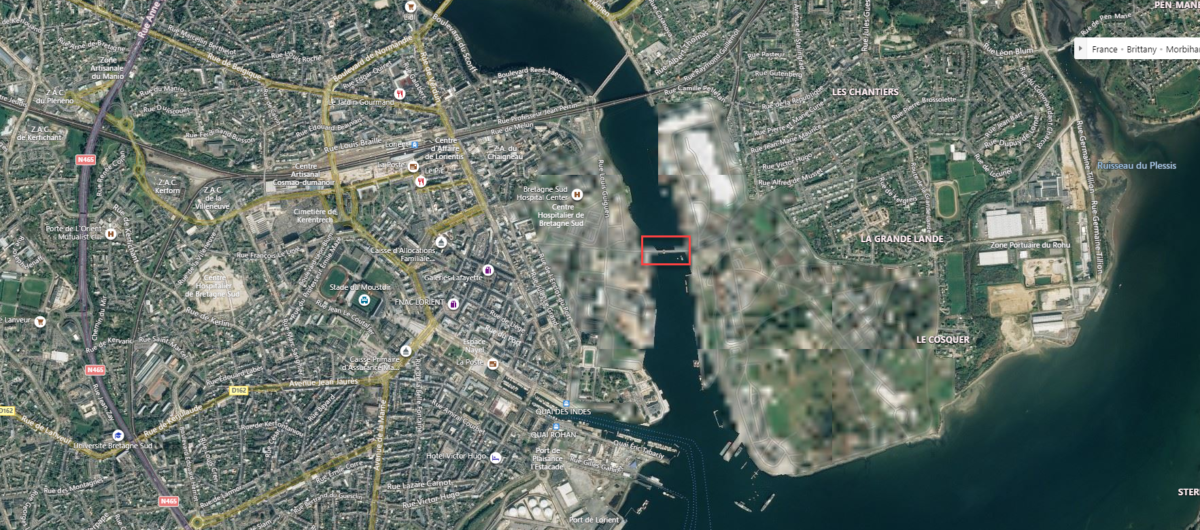

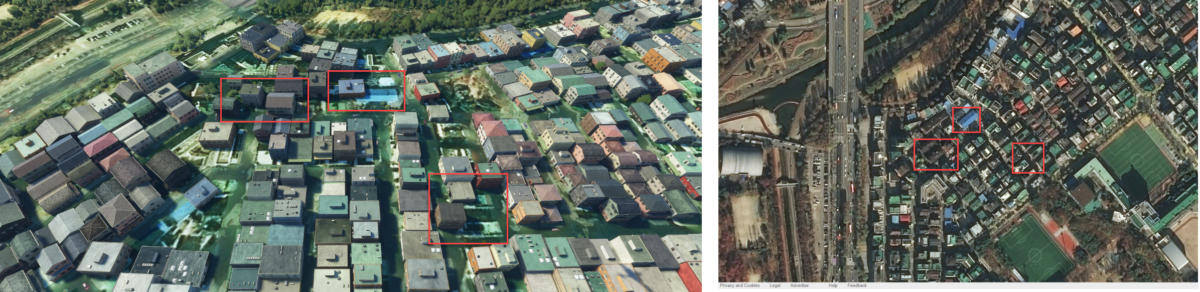

In the images below, you can see that while the game rendered some buildings inside this army base in Lorient, France, it failed to render many that are visible in this un-pixelated satellite image:

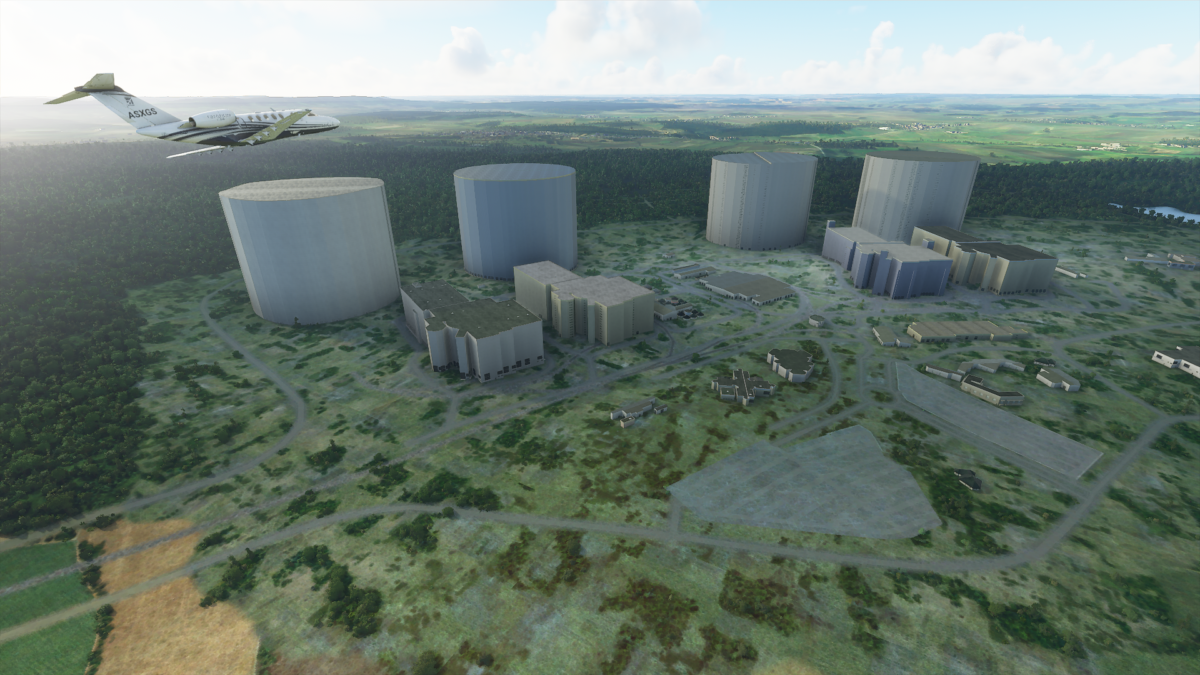

The game also rendered the cooling towers and other buildings inside the Cattenom nuclear power plant in France, even though the satellite image that appears in Bing Maps is both pixelated and obscured by steam clouds:

Note that the game has rendered the buildings in the power plant despite them being obscured in the satellite image below (Source: Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020)

Conclusion

MFS2020’s simulated world is visually stunning and immersive, making for a memorable gaming experience. As a tool for open source investigations, the game has some potential. The game’s ability to populate cities and towns with 3D models is a big part of what makes it fun to play, but as it stands it has very limited potential to aid in geolocation given the inaccuracies that we observed. More generally, the game’s rendering of topographical features — combined with its dynamic weather and time feature — could help researchers visualize the places with which they are working.

Simulating a 1:1 replica of our planet with high graphical fidelity and populating it (if imperfectly) with objects is an impressive feat, and a clear stepping stone for future simulation technologies.

Thanks to Aric Toler for helping out with this article.