Bahamut Revisited, More Cyber Espionage in the Middle East and South Asia

Introduction

In June we published on a previously unknown group we named “Bahamut,” a strange campaign of phishing and malware apparently focused on the Middle East and South Asia. In the Bahamut report, we documented a capable actor interested in a diverse set of political, economic, and non-governmental targets, which suggested espionage rather than criminal intent. Bahamut was shown to be resourceful, not only maintaining their own Android malware but running propaganda sites, although the quality of these activities varied noticeably.

Our publication on the campaign coincided with a series of defacements and leaked emails related to Qatar and its neighbors, the same types of targets that arose in our research. While we have found no evidence to link the group to these incidents, Bahamut provided a useful window into the activities rampant in the Gulf at a time when hacking has contributed to a regional diplomatic crisis. The incident further demonstrated the blurred lines in cybersecurity between attacks against human rights communities and espionage against diplomats, as well as the potential role of non-state actors in state-aligned cyber operations.

After publication, the identified operations and malware domains were taken down. For three months there was no apparent further activity from the actor. However, in the same week of September a series of spearphishing attempts once again targeted a set of otherwise unrelated individuals, employing the same tactics as before. Bahamut remains active, and its operations are more extensive than first disclosed. Our primary contribution in this update is to implicate Bahamut in what are likely counterterrorism-motivated surveillance operations, and to further affirm our belief that the group is a hacker-for-hire operation. Toward this we document a previously unnoticed link with a campaign targeting South Asia that was published last year. This post extends the previous publication with recent activity and lends more evidence to our past hypotheses about the political nature of its operations.

Overlap with Previous Campaigns

Our initial observation of the Bahamut group originated from in-the-wild attempts to deceive targets into providing account passwords through impersonation of platform providers. After unpacking the larger targeting of the attacks, the credential theft operations were found to cover a broad range of interests in the Middle East, such as Turkish diplomats and Iranian political figures in the lead up to the recent presidential election. As we noted then, these incidents stood out because they exceeded the level of care and preparation seen in the everyday cybercrime. In our report, we also noted a similarity to the “Operation Kingphish” campaign published by Amnesty International earlier this year. As we wrote then, compared to Kingphish, Bahamut “operates as though it were a generation ahead in terms of professionalism and ambition.”

A more recent credential theft attempt provided the most credible link between the two campaigns thus far, and bolsters our hypothesis that the operations are related. Among a flurry of spearphishing attempts associated with Bahamut in recent weeks, one fake Google message directed its target to a unique domain (string2port[.]com) to steal login credentials. The string2port domain (registered in May 2016) strongly reflects the ping2port[.]info domain (registered in September 2016) that was used in Kingphish against Qatar-focused labor rights advocates. The ping2port domain is now pending deletion – abandoned due to discovery – but the previously unnoticed and related string2port has been reused. Given the similarities in tactics, administration of infrastructure, domains, and other factors, it appears increasingly clear both campaigns against Middle Eastern diplomats and those directed against human rights advocates are connected.

The similarities to other research is not limited to Kingphish, and includes a prolific campaign in South Asia. In our original post we noted that an expansive operation was evident from a search of potential domains based on common pattern in domain registration and hosting behavior (an Anglo-European name sometimes followed by a number at mail.ru, often also found in the DNS ‘Start of Authority’ record). Here too, we find multiple other candidate domains based on simple search patterns, although other email providers such as Pobox.sk are now more common. While we published a number of domain names that were clearly malicious and similar to Bahamut, we did not post the full list out of a concern of false positives. Included in these results was a domain i3mode[.]com, which used a Mail.ru contact email and was hosted on a network found in other Bahamut spearphishing attempts.

Whois (i3mode[.]com):

Registrant Name: KEDRICK BROWN

Registrant Phone: +503.503226605642

Registrant Email: KEDRICK.BROWN.84@MAIL.RU

This domain appears in Kaspersky’s blog post “InPage zero-day exploit used to attack financial institutions in Asia” from November 2016. That campaign targeted financial institutions with malware that took advantage of a vulnerability in text processing software popular with Urdu and Arabic speaking users. The domains in the InPage campaign match the same pattern of registration and hosting within Bahamut. The Urdu connection recalls our identification of Android malware posing as a Urdu Quranic reference. This thematic overlap also includes a relevant sample “Analysis Report on Kashmir.exe,” which would be of interest to a South Asian audience. Additionally, another sample connecting to the i3mode domain (“E-Challan.zip”) appears to be a reference to receipt for payment or delivery specific to India and Pakistan. The staging domain for that malware also has another subdomain that appeared to reference an Indian business newspaper (“mint-news-portal.hymnfork.com”).

This faint connection in domains and similar interests provides a first hint that Bahamut is more active than we were previously aware and bolsters our hypothesis that the group is a hackers-for-hire operation.

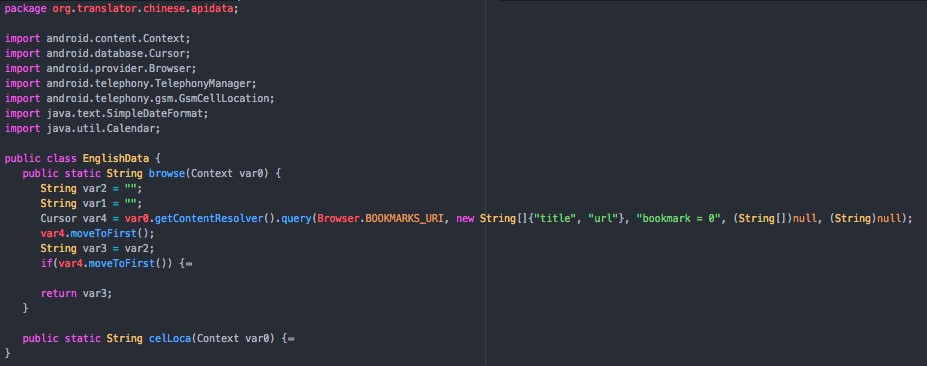

Malware Campaigns in South Asia

In the Bahamut report, we discussed two domains found within our search that were linked with a custom Android malware agent. This connection between the malware and credential theft was reinforced by some similarities in how the agent reported back to the attacker’s servers, and thus we felt moderately confident about a link between the credential theft and the malware. After the publication of the original report, these sites were taken offline despite the fact that one agent was even updated a six days prior to our post (the “Khuai” application). Additionally, antivirus engines began to detect copies of this malware based on common patterns in development, including apps that we were not aware of. Based on a search of public sources, we find three more malicious applications focused mostly on South Asia, including samples uploaded from India.

Included in the newly detected apps was one named “Devoted to Humanity,” which has been taken down from the Play Store (devoted.to.humanity). Based on the name and domains used in the communications (“devotedtohumanity-fif[.]info”, which was registered in March 2016), it appears that the application impersonates the “Falah-e-Insaniat Foundation” (FIF) that ostensibly operates as a religious charity primarily in Pakistan. FIF is notable for its links to the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) terrorist organization, which has committed mass-casualty attacks in India in support of establishing Pakistani control over the disputed Jammu and Kashmir border region. As a result of its connections to LeT and international pressure to crack down on Kashmiri jihadists, Pakistan placed FIF under on a terrorism watch list in January 2017. The development of a malware agent relevant to Indian and Pakistani security interests, timed with increased international scrutiny on FIF, suggests a counterterrorism and intelligence motive for Bahamut’s espionage.

The “Devoted to Humanity” app also references an image hosted on domain voguextra[.]com, which appears to have been used to stage decoy documents.

The Falah-e-Insaniat Foundation app is not the only Kashmir-related campaign associated with Bahamut. Pivoting off the unique contact information used to register the FIF domain, “adgnad dangda” and “adgnad@mail.ru”, we also find two more (“Android-Cloud.net” and “Kashmir-Weather-Info.com”) that were cohosted on the same server as the FIF site. The Kashmir Weather domain corresponds with a now-removed Android application with the similar set of permissions and tactics found in the previous malware (com.weather.kashmir). The purpose of the “Android-Cloud.net” domain is not currently known.

It is important to note that the domains had lapsed and were re-registered since they were first used. So while they appear to be malicious, the current custody is unclear. The domains now purport to be for a platform “Donkey Service” (“DoDoDonkey”), which provides a less than credible pitch:

Donkey Service has incredibly large network and infrastructure to stop really large attacks on the Mobile system.

We just get clean requests and never have to deal with malicious traffic or attacks on the Mobile infrastructure. We are the perfect partner for our business!

Much of this text is copied from a customer quote about Cloudflare.

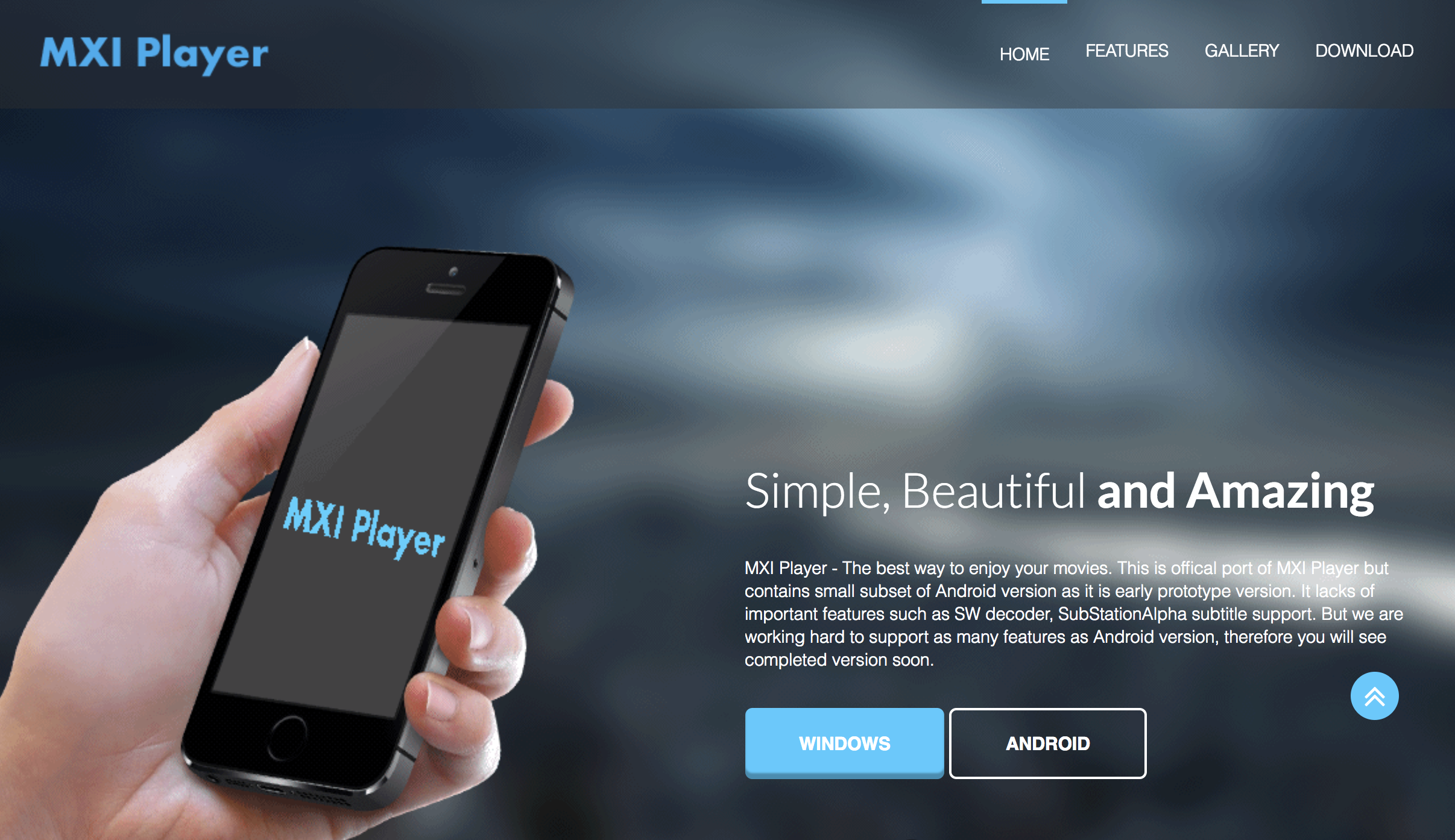

As with the “Khuai” Chinese-English translator malware in the previous post, other identified agents have unclear targets, such as the “MXI Player” that was last updated August 2017 (mxiplayer[.]com). MXI Player appears to be a version of the Bahamut agent, designed to record the phone calls and collect other information about the user (com.mxi.videoplay). After having been kicked off Play Store several times, it appears that Bahamut is now hosting its agent on the APKPure alternative app store. However, the malware retains certain design choices seen in previous attacks, for example around encryption and communications with the attacker server. As a result, it is already flagged as Bahamut by antivirus engines.

More interestingly, the MXI Player site also includes a Windows version of the application, which is a rebranded media player that also installs a malware agent posing as a software updater (mxiupdate.exe). A full write up of the Windows malware is not in scope of this article for the sake of brevity and our intended contribution. A hash for the malware agent is provided in the appendix for those interested. A cursory inspection of debugging artifacts and other details, such as an embedded filesystem path referring to a template code project (“EmbeddedAssembly_1.3”), suggests that the agent is both rudimentary and custom designed.

One important trait worth noting is that the Windows malware’s communications strongly resembles the malware connected to the domains disclosed by Kaspersky. These similarities include same approach of communication beacons to a randomly-named path on the attacker’s server, with the same URL parameters that contain similar types of values (probably AES encrypted strings represented in base64, like the Android applications):

Bahamut’s Mixi Player malware (mxiplayer[.]com):

/hdhfdhffjvfjd/gfdhghfdjhvbdfhj.php?p=1&g=[string]&v=N/A&s=[string]&t=[string]

InPageCampaign malware (encrypzi[.]com):

/fdjgwsdjgbfv/dbzkfgdkgbvfb.php?p=1&g=[string]&v=0&s=[string]

These repeated parallels further indicate a relationship between the Android malware operations and the InPage-related espionage. In review, these connections include:

- Overlap between the extended network of domains relevant to Bahamut’s credential theft infrastructure and malware domains in Kaspersky’s report;

- Similarity in the format of beacons between Bahamut’s Windows agent and malware associated with the InPage domains, and to a lesser extent even in the Android agent; and,

- Commonalities in targeted interests, namely the contested Kashmir region.

One curious trait of Bahamut is that it develops fully-functional applications in support of its espionage activities, rather than push nonfunctional fake apps or bundle malware with legitimate software. These include translation and weather applications that involved requests to third-party APIs and other user interactions. While much of the code appears to be copied and these applications are simple, Bahamut must spend a fair amount of time on operations that target a small number of individuals. The content and app market descriptions of the three Android applications also recalls our previous observation that the Bahamut actor appears to be fluent in English, albeit constrained either due to not being native speakers or lack of professionalism.

Credential Theft in the Middle East

Bahamut has taken a more concerted effort to reduce exposure of their operations, preventing the research techniques that led to our cataloguing of their infrastructure and operations in the first post. Once again, the attempts all originate from less reputable hosting companies and networks (AS44901, BelCloud Hosting Corporation). Spearphishing pages are now more resistant to enumeration attempts and appear to use a dedicated subdomain for one specific victim. The unique subdomain appears to be automatically disabled after the “successful” phishing attempt in order to cover the trail of the attack (redirecting the user elsewhere or appearing to be a Google error page). These pages have also increased their use of unicode replacements for letters and other font tricks as a way to evade network filters or to deceive users (e.g. using r and n, “rn”, to appear like the letter “m”). Altogether an already stealthy actor has improved their operational profile.

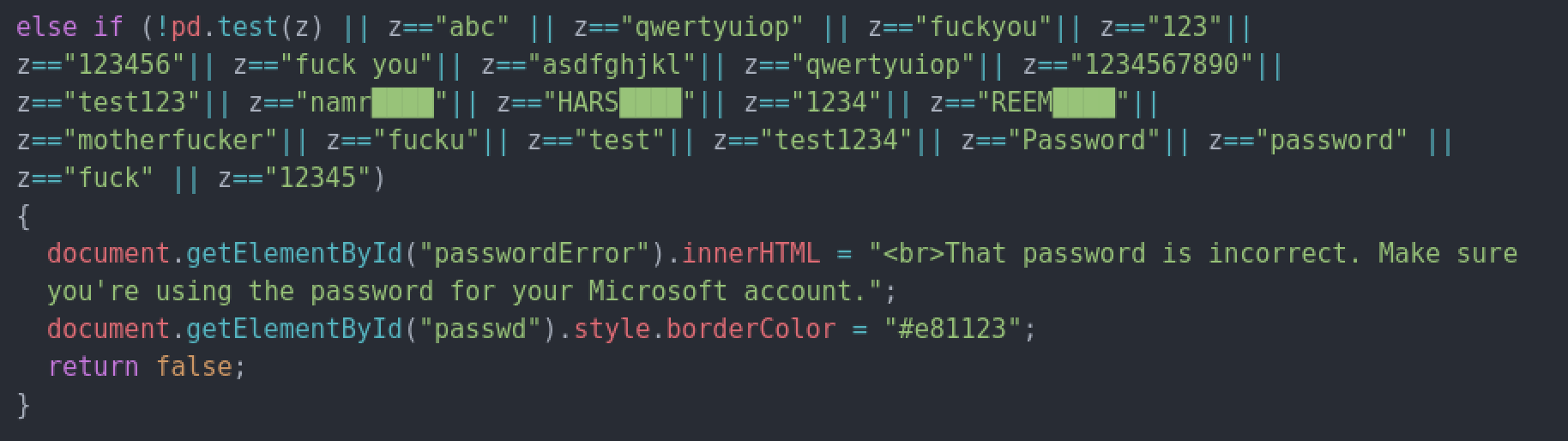

Curiously, Bahamut appears to track password attempts in response to failed phishing attempts or to provoke the target to provide more passwords. These passwords are hardcoded in the phishing page so that the login form will immediately return a “bad password” message if entered. This could be designed to trick the user into providing older passwords or alternative passwords used on other platforms to provide a foothold into other services. The result is that Bahamut spearphishing pages include over two hundred possible real world passwords that appear to cover at least a couple of dozen likely victims.

The theme of the passwords provide indication of the types of targets and victims of Bahamut since our last encounter. Most of the domains clearly reflect a Middle Eastern audience, including referring to individuals’ names (e.g. “al Khalifa”) and Emirati phone numbers. Some of these passwords are cryptic – such as one referencing a supermarket in Beirut. Others reference a “national bloc,” Gaza, the Dubai Expo in 2020, and a Saudi media entity. More generally, these targets appear to include people or entities in the United Arab Emirates, Morocco, Jordan, Libya, and Bahrain, among other Arab countries. Further demonstrating its focus on the Middle East, the phishing page specifically (and exclusively) checks if the visitor’s browser is set to the Arabic language and redirects them to a translated page. Where targets are personally identifiable, these campaigns reflect an intimate understanding of the relationships and members of the policy and international relations sectors of certain Gulf states – information that would not be readily accessible to a bystander, and targets that would not be of interest outside of political motivations.

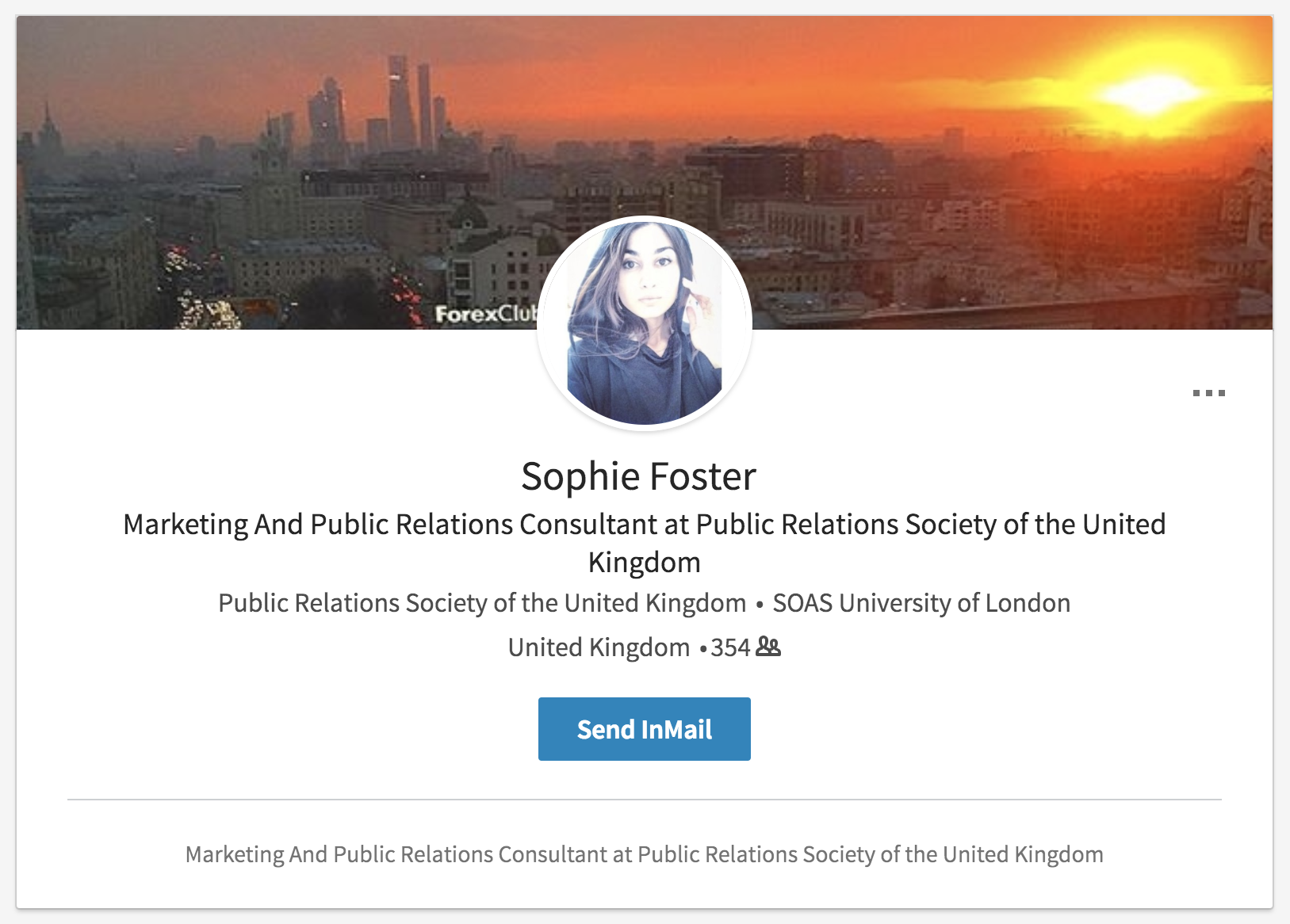

The recent incidents also involved a social engineering tactic well documented in the Kingphish report: fictitious social media profiles. In Kingphish, a profile active on LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook (purporting to be an IT and business professional) approached labor rights advocates requesting help on research about human trafficking.

Similarly, a fictitious LinkedIn profile named “Sophie Foster” attempted to simultaneously approach multiple targets of Bahamut’s phishing messages. The Foster profile appears crafted for a professional Middle East related demographic, claiming to have experience in public relations and international trade. Among connections to SOAS and LSE students, which appear to be cover related to her claimed educational background, the profile has a clear theme in targets: journalists and public relations professionals in the Middle East, including individuals at Sky News Arabia and Al-Masry Al-Youm, and others in Egypt, Lebanon, Saudi, UAE, and Turkey. A two-year old Facebook profile exists for the persona, which has liked pages for Lebanese politicians and has a Mail.ru account linked to it.

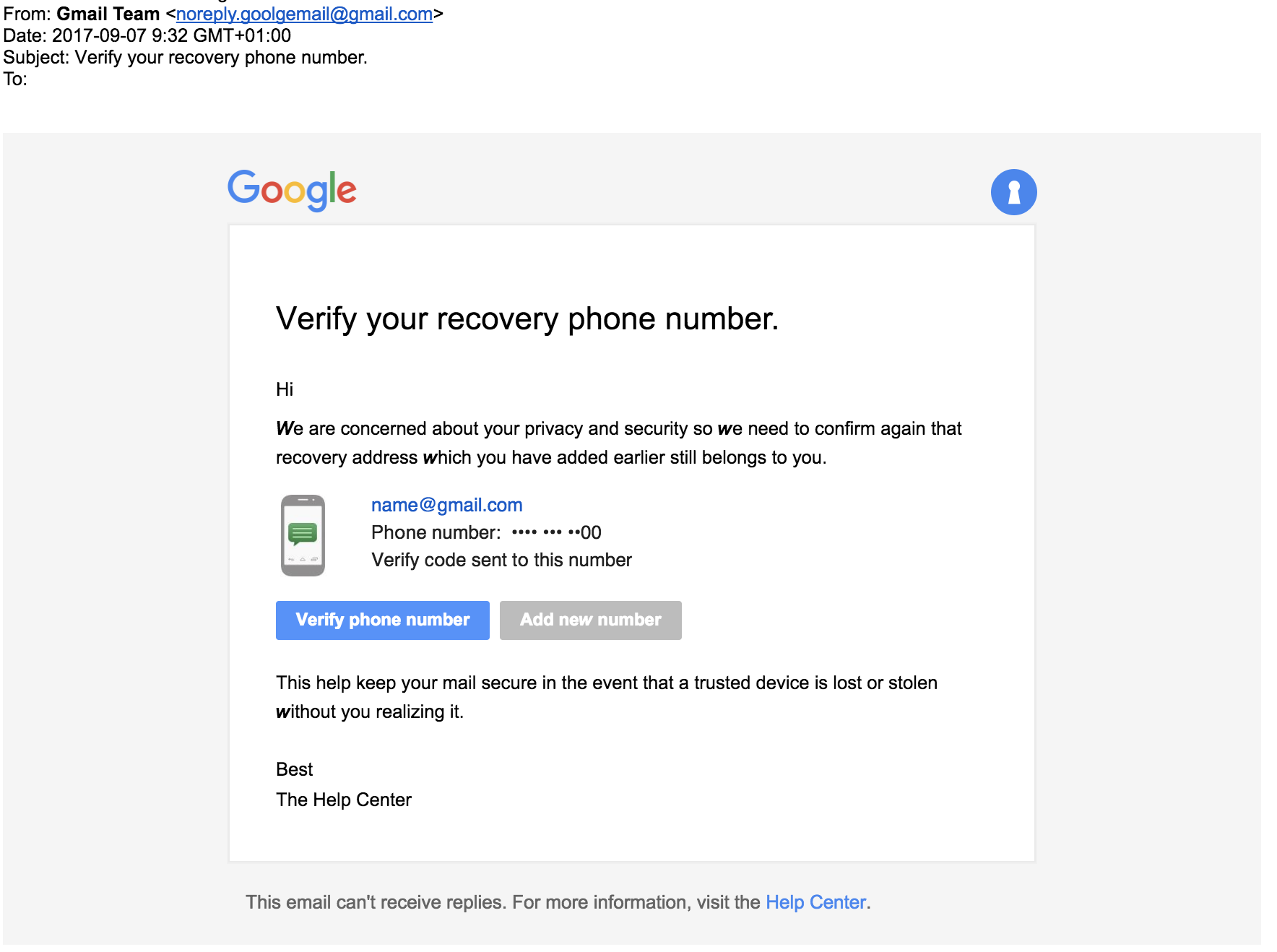

Bahamut spearphishing attempts have also been accompanied with SMS messages purporting to be from Google about security issues on their account, including a class 0 message or “flash text.” These text messages did not include links but are intended to build credibility around the fake service notifications later sent to the target’s email address. The use of fake sender identifiers – especially combined with the unusual flash text approach – could be effective, but once again Bahamut is betrayed by its unusual English.

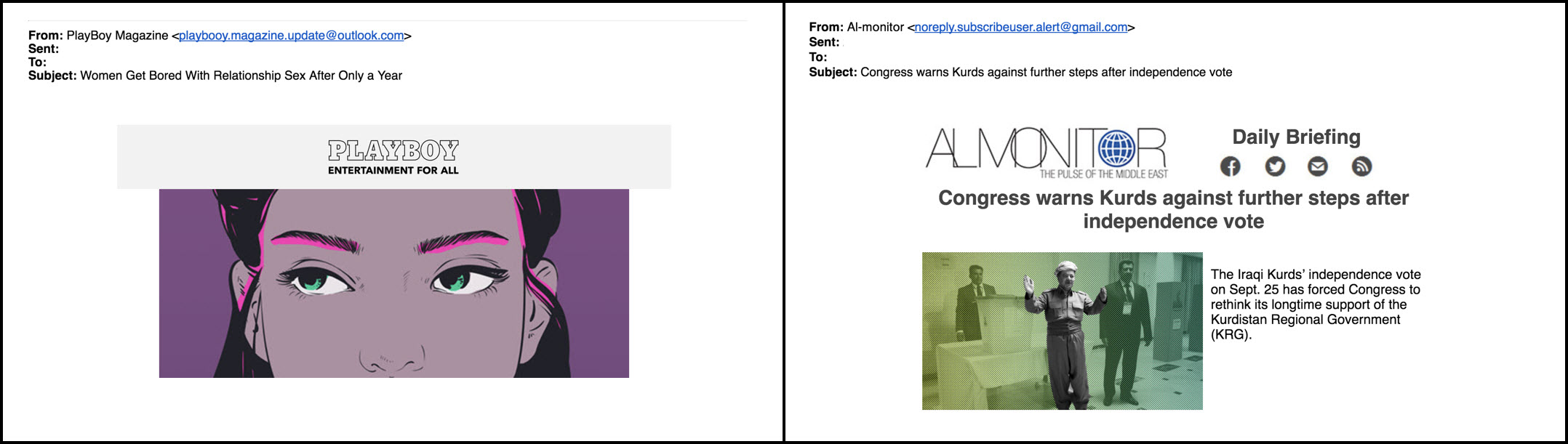

Bahamut also appears to be more aggressive in reconnaissance against targets. As it harvested potential addresses associated with targets, it would sended tailored or salacious messages with image-based trackers to check if the message was opened. These provide a metric as to whether the target is ignoring attacks, or whether the email address is not monitored or active. The messages were crafted to a Middle East focused audience, primarily posing as news stories or media outlets (e.g. Al Monitor) relevant to the region.

Conclusion and Implications

Given our increased confidence that Bahamut was responsible for targeting of Qatari labor rights advocates and its focus on the foreign policy institutions other Gulf states, Bahamut’s interests are seemingly too expansive to be limited one sponsor or customer. However, those targets fall within coherent themes. It is unclear which single client could be interested in both a Kashmiri organization on a terrorism watchlist and Egyptian journalists. Thus far, Bahamut’s campaigns have appeared to be primarily espionage or information operations – not destructive attacks or fraud. The targets and themes of Bahamut’s campaigns have consistently fallen within two regions – South Asia (primarily Pakistan, specifically Kashmir) and the Middle East (from Morocco to Iran). The targeting of organizations scrutinized ties to terrorism raises the stakes for the operation, and differentiate it from usual cybercrime. Targets outside of the Middle East tend to still have associations to Middle Eastern issues, such as a European investment firm active in a Gulf country and a foreign policy experts in the West. We have not found evidence of Bahamut engaging in crime or operating outside its limited geographic domains, although this narrow perspective could be accounted for by its compartmentalization of operations.

There remains ample questions and research opportunities to be explored. While Bahamut has leveraged resources in Urdu and Arabic, it appears to be most comfortable in the English language despite its uncommon grammar. While we note malicious domains that maintain a similar profile to Bahamut that impersonate Qatari government email services, we have not found a direct connection to those campaigns, and there has been little indication of the targeting of Qatar within our monitoring. We have not fully explored the extent of Bahamut’s operations, such as its Windows malware agent or possible other Android malware. Moreover, the networks and tactics used within Bahamut’s operations turn up suspicious sites that resemble the Times of Arab operation disclosed previously – often Middle East focused news published in English that recirculate content on technology and politics with no clear attribution or purpose. These suspicious sites and those we can account for as Bahamut repeatedly turn up a nexus with India, more so than the Middle East, despite attempts by the attackers to stay anonymous. Once again, our investigation only seems to be a limited window into a strange operation.

The proposition that a non-state hacker-for-hire operation could be used in pursuit of regional state interests is not unusual. At this point most Middle Eastern governments have at least once procured cyber espionage capabilities from abroad, such as from the government malware vendors FinFisher, NSO and Hacking Team. By one account, Qatar even sought to outsource an offensive cyber program to American companies – a deal that was quashed by the U.S. government. This reliance on contractors could indicate that such countries have been unable to develop their own in-house capacity, which would align with their general reliance on foreign military firms. It is also worth noting that while some government agencies may have acquired tools already, other entities such as local police might still desire their own capabilities leading to overlaps. On the vendor side, in recent years companies such as the Indian-firm Aglaya have been implicated in selling full hacking as a service, rather than simply providing tools for government use. This parallels the unclear lines between cybercrime and espionage seen elsewhere, and hints that mercenary cyber operations are more common than currently understood. Thus Bahamut warrants attention as an emblematic case of the interest in cyber espionage in places such as the Middle East and the range of vendors willing to meet that demand.

Acknowledgement

We appreciate the help from Tom Lancaster, who noticed the overlap with Kaspersky’s InPage report and an additional Android malware agent. Our prior publication also failed to acknowledge immensely valuable input from a number of colleagues, including Nadim Kobeissi’s feedback on how the API endpoints on the Android malware were encrypted. Thank you to everyone who contributed to this research and provided feedback.

IOCs

Credential Harvesting and Recon

noreply.user.subscripton@gmail[.]com

mirror.news.live@gmail[.]com

mail.noreplyportals@gmail[.]com

rnicrosoft-recovery-update@hotmail[.]com

noreply.subscribeuser.alert@gmail[.]com

noreply.users.validation@gmail[.]com

noreply.applc.id.service@gmail[.]com

noreply.user.subscripton@gmail[.]com

playbooy.magazine.update@outlook[.]com

noreply.goolgemail@gmail[.]com

dubaicalender.eventupdate@outlook[.]com

sputniknews@email[.]com

news_update@email[.]com

bbcnewsdailysubscribe@gmail[.]com

rnicrosoft-recovery-update@hotmail[.]com

noreply.goolgehangouts@gmail[.]com

squre39-cld[.]info

goolg-en[.]com

login-asmx[.]com

string2port[.]com

session-en[.]com

singin-go-olge[.]com

111.90.138[.]81

188.68.242[.]18

91.92.136[.]134

200.63.45[.]47

Android Agent

devotedtohumanity-fif[.]info

kashmir-weather-info[.]com

mxiplayer[.]com

6e5e7ecb929fdc29ba93058bf2f501842ac0f2c0 Khuai Translator (1.3)

0550dad8d55446e5b5dbae61783cfb7c78ee10d2 MXI Player (1.2)

00d000679baab456953b4302d8b2a1e65241ed12 Devoted to Humanity (1.0)

ddaf5e43da0b00884ef957c32d7b16ed692a057a Kashmir Weather (1.2)

Windows Agent

9850ac30c3357d3a412d0f6cec2716b63db6c21d

mxiplayer[.]com

Other Malware References

“Analysis Report on Kashmir.exe” 9e4596bfb4f58d8ecfe2bc3514c6c7b2170040d9acfb02f295ed1e9ab13ec560

“E-Challan.zip” 1518badcb2717e6b0fa9bdd883d5ff61fedddf7ddf22cc3dc04a38f4e137fc96)

mint-news-portal.hymnfork[.]com

online-tracking-status.hymnfork[.]com

Similar Infrastructure

insidecloud-aspx[.]com

data-covery[.]com

sa-google[.]com

rnail-aspx[.]com

session-service[.]com

session-owa[.]com

myinfocheck[.]com

host-auth[.]com

janko.kolar@bulletmail[.]org

jacbov.vjan@bulletmail[.]org

robert.warne@list[.]ru

viera.taafi@pobox[.]sk

aaron.drago@pobox[.]sk

marek.franko@pobox[.]sk

oliver.dagur@mail[.]ru

ralph.cramey@mail[.]ru

petru.negru@pobox[.]sk