Testing for Manipulation: A Case Study from Colombia

On April 17, Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro took to Twitter and wrote “Manipulations of the extreme right. Lies as the basis of politics. Here, Camilo proves photo manipulation.” He referred to a tweet by the journalist Camilo Andrés García, who shared an analysis by Ghost, a filter used in conjunction with other image analysis tools, to support his doubts about the authenticity of a photo of a man in camouflage standing by a road in the Colombian countryside.

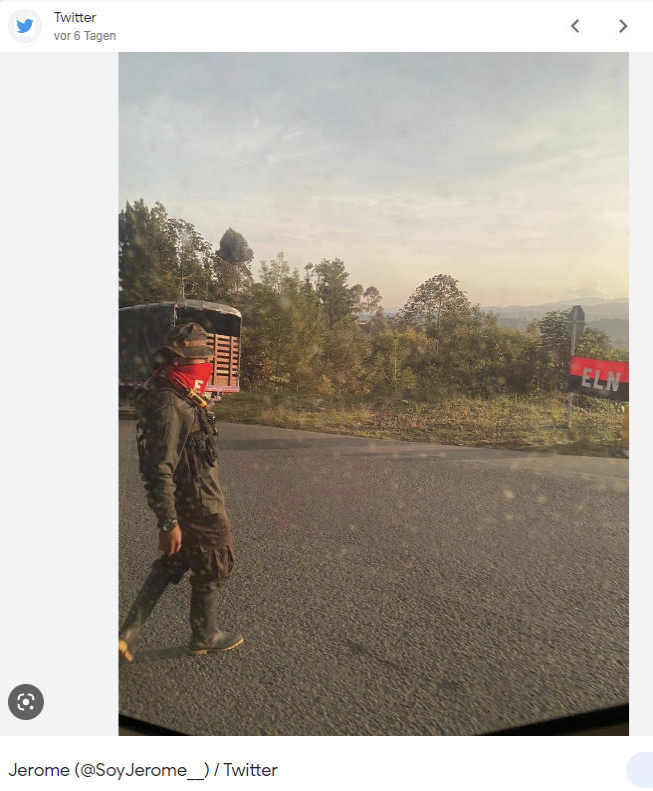

This man, wearing a red bandana, stands in view of a flag of the far-left National Liberation Army (ELN), a guerilla group which fought the government in a long-running conflict which has seen hundreds of thousands of Colombians killed. While a 2016 peace agreement saw another guerilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) come to terms with the Colombian government, peace talks with the ELN are ongoing, with Petro previously pledging to bring total peace to Colombia.

President Petro, himself a former guerilla, has been described by international media as the country’s “first leftist president”. Meanwhile Paloma Valencia, who first shared the image on Twitter on April 15 and another photo two days later, is a senator for a right-wing opposition party. On April 17, Valencia also shared video footage of armed men entering a town.

Fact-checking website ColombiaCheck asked Bellingcat for help in verifying the photo and assessing claims about its possible manipulation. The website’s editor José Sarmiento explained the political context of the claim, noting that Petro’s “total peace” approach of negotiating with illegal armed groups has angered Colombia’s right-wing. He added that Valencia has been one of the leading voices against such processes and that she argues that armed groups only use them as opportunities to grow stronger.

“The idea behind her tweet was to show that Petro is letting this happen because they believe that as a former guerilla man himself he is close to subversive criminals, a common right-wing narrative that has usually been fed by using disinformation”, said Sarmiento in an email.

Using a few simple online tools and techniques, Bellingcat could confirm the photo’s location and found no clear signs of digital manipulation. Here’s how we did it.

Finding the Right Spot

It’s important to note that recycling old images or videos is a more common method of spreading disinformation than sophisticated image manipulation. This is why a reverse image search should always be the first step in verifying imagery.

When dealing with images appearing on social media, it is wise to find their very first appearance – this allows you to compare it with later, and often more popular, iterations which could be shared by actors with varying agendas. The earliest instances which Bellingcat could discover of this image being shared online also came from April 15, by the Twitter user Esteban Merchan.

The second image, which Valencia shared on April 17, was first posted by the Twitter user @Soy_Jerome that same day, but was deleted shortly after.

It’s also crucial to geolocate the imagery: determining where it was taken by comparing it with reference material. Valencia gave a lot of information in her Tweets. But geolocation means that we don’t have to take her at her word when she wrote in the April 15 Tweet that the photo was taken at an intersection of the Pan-American Highway near Totoró in Cauca province. In an April 18 Tweet she added that the precise location was nine kilometres’ drive from Paniquitá.

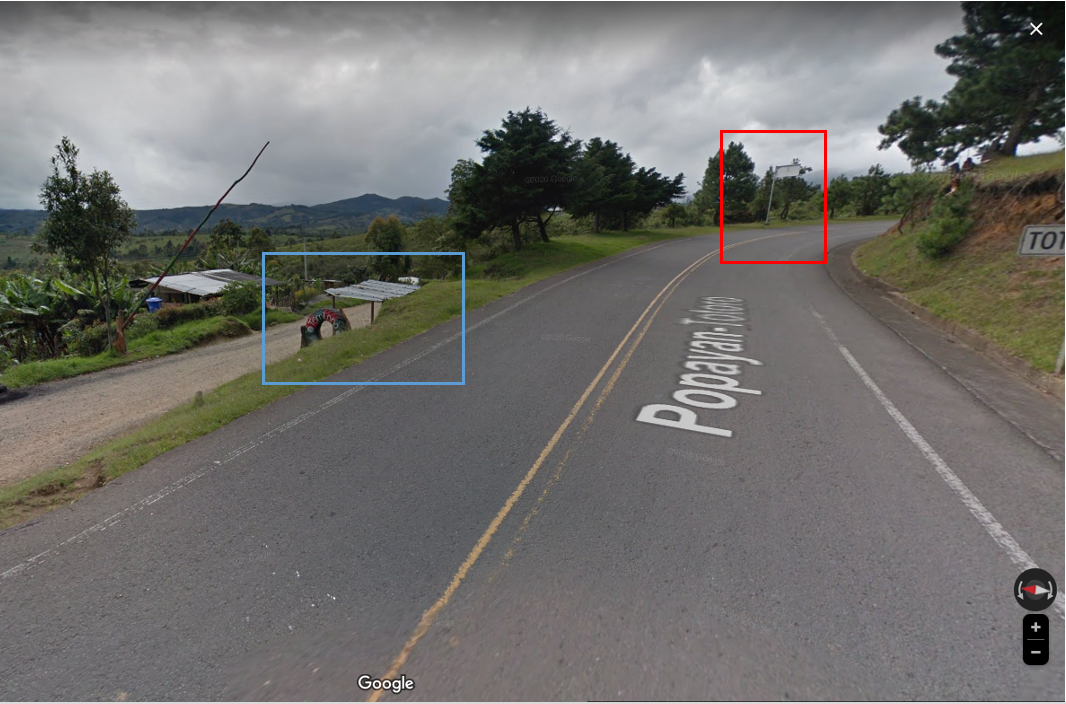

Helpfully, Google Street View from 2019 is available for the highway between Totoró and the city of Popayán, which passes an intersection with the road to the aforementioned town of Paniquitá. By following the highway towards Popayán and checking every junction carefully for matching features, a match can be found at 2.511, 76.499337.

When comparing the tweeted images with the street view images, there are still some differences to be seen in the intersection of the two roads. These can be explained and checked using Google Earth Pro and comparing satellite images throughout the years.

On April 15, the Colombian media outlet Enfasis also published imagery to its Facebook page which showed an ELN flag, and claimed that the group had been “marking territory” along the road to Totoró. This imagery was taken at the same intersection where the camouflaged individual was seen.

Comparing the streetview with the image shared by Enfasis shows still elements present in both images:

The video which Valencia shared on April 17 is harder to locate. It shows a group of armed men wearing red bandanas walking the streets of a town; she claims that these are ELN fighters entering Paniquitá — the next settlement down the road from the junction seen in the photo previously geolocated.

As the town is small and Google Street View is not available, reference imagery from other sources is required.

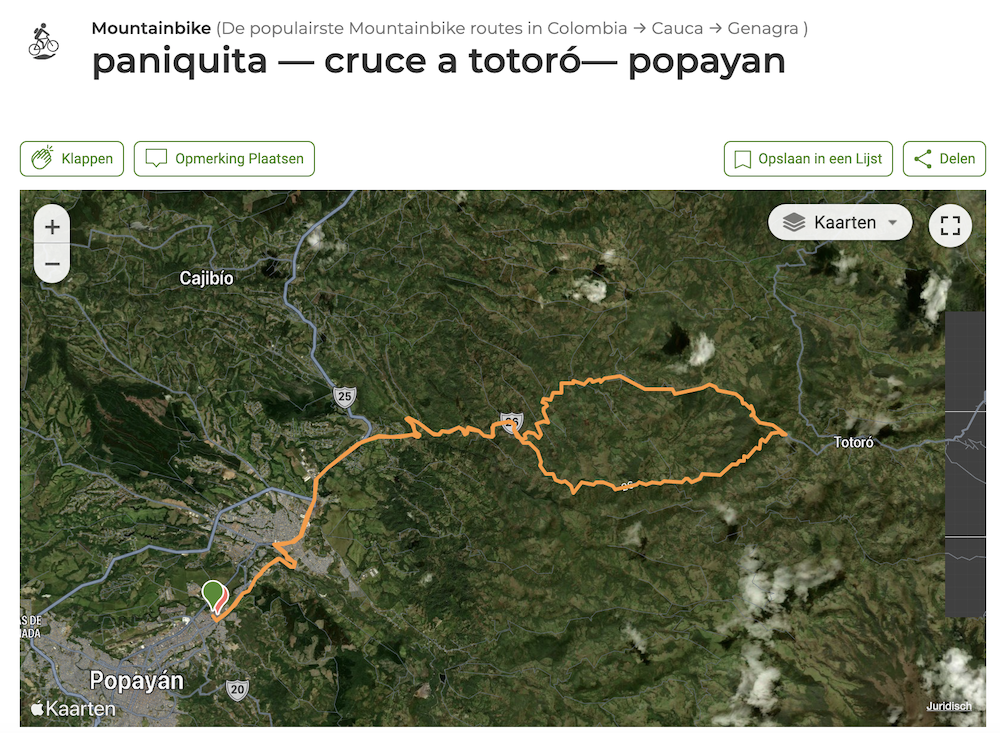

A Google search for Paniquitá led to a page on WikiLoc, a website which markets itself as the best place to discover outdoor trails for hiking and cycling. In 2018, a WikiLoc user shared a 60 kilometre mountain bike route from Popayán to Totoro and back again via Paniquitá.

Many mountain biking enthusiasts upload their footage to YouTube, where a search for ‘MTB [Mountain Bike] Paniquitá’ found the following video:

At 2:19, the mountain biker passes a street where the same building can be seen as in the video posted by Valencia. This confirms that the video on Twitter was indeed recorded in Paniquitá.

Now that we have the location, we can also establish the direction the camera faced in the video from Paniquitá which was shared by Valencia.

Deceptively Difficult

Before getting to digital tools at all, it’s important to consider exculpatory context and other reasons which may explain what seems at first glance like an odd image or video. For example, García claimed in his initial Tweet that there was no other imagery of the ELN in the area, which roused his suspicions. But such imagery later surfaced.

Although the photos of the camouflaged individual could not be conclusively chronolocated – that is, establishing when they were taken from features in the imagery – they had also not previously appeared online. And as ColombiaCheck reported in their Spanish language text, there had actually been media reports of ELN activity in this immediate area around the time that the photos were taken.

What’s more, citing a 2009 study, ColombiaCheck’s article explained in some detail why a digital tool might detect false positives or false negatives in analysing a JPEG photograph for anomalies.

While the Ghost tool appeared to highlight anomalies on just the ELN flag and bandana worn by the individual in the picture, ColombiaCheck used the FotoForensics platform and found no significant signs of manipulation.

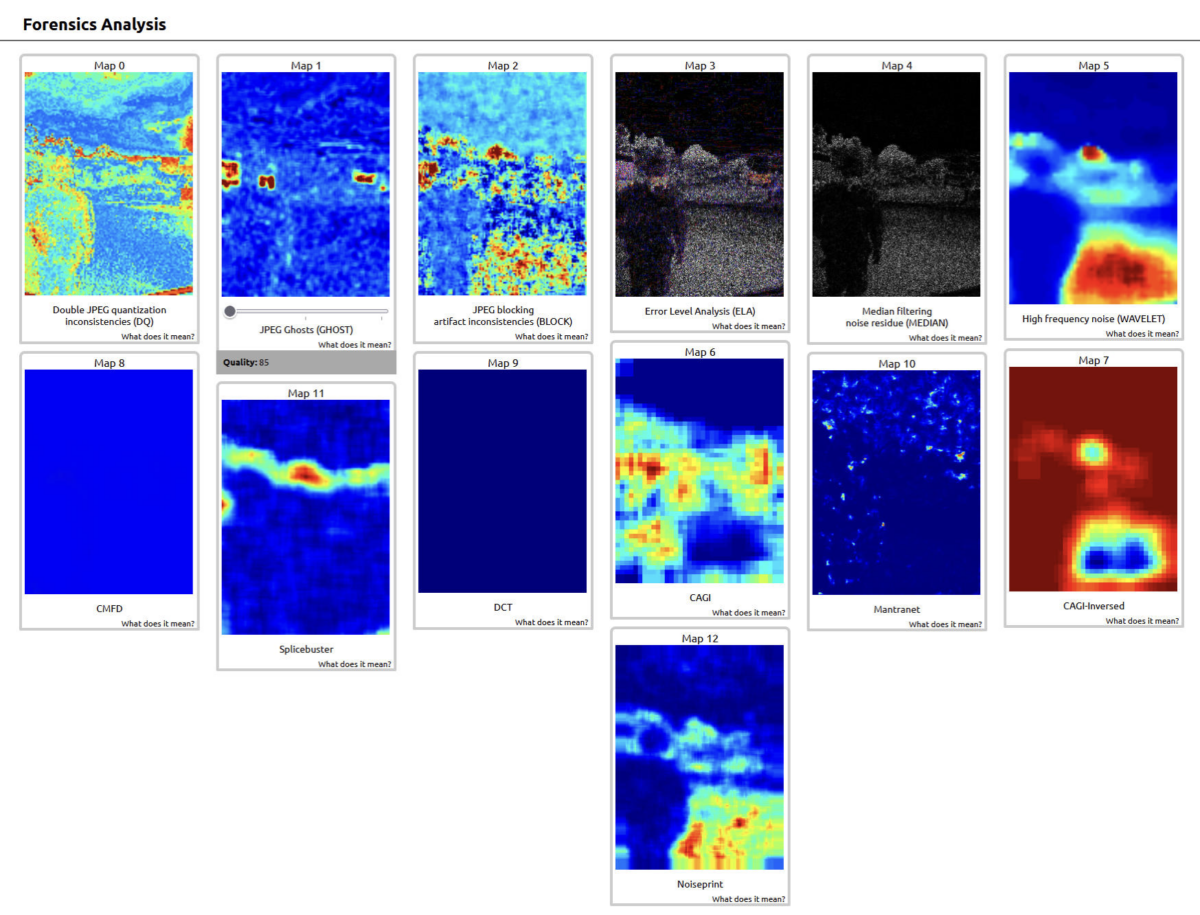

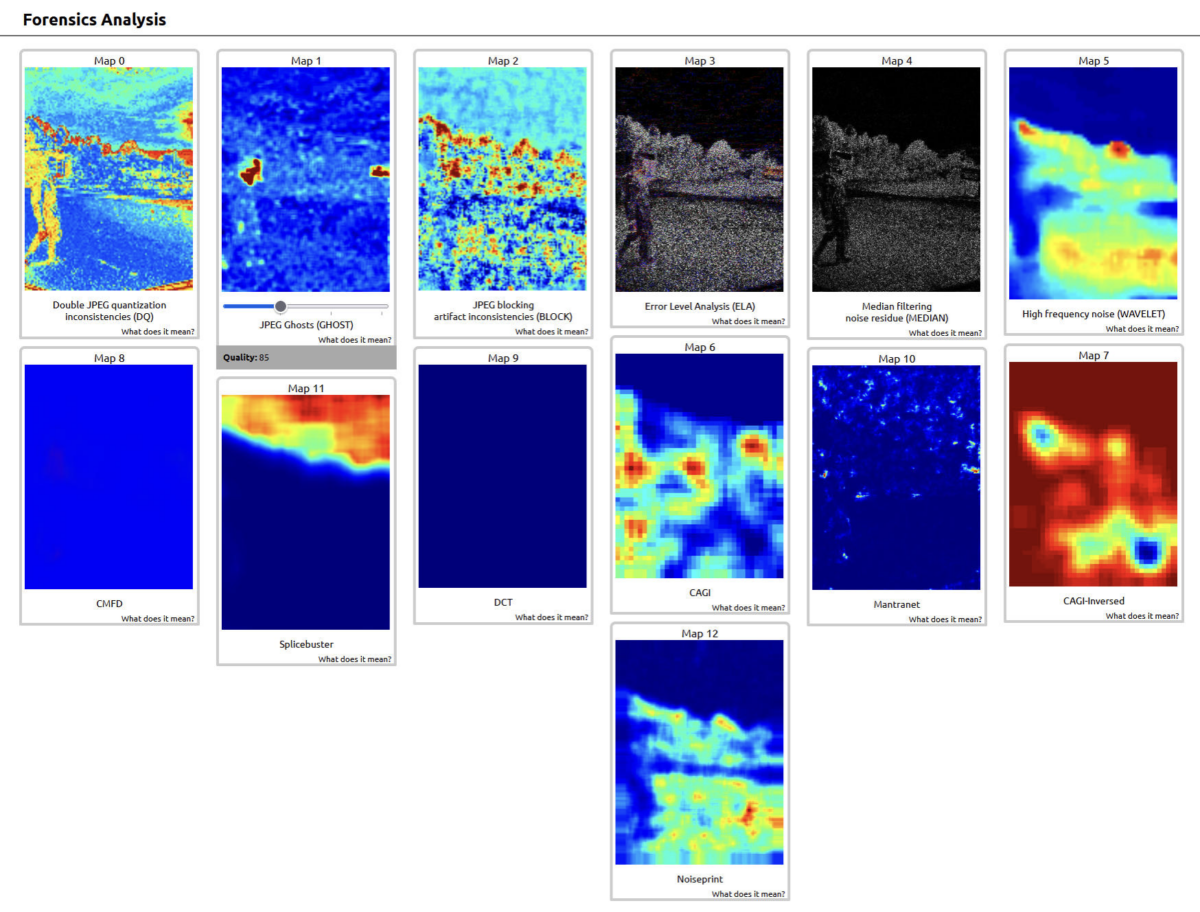

Bellingcat contributor Timmi Allen, meanwhile, ran the images through a number of other tools, which showed a variety of results highlighting as anomalous (in red) completely unrelated areas of the images or in some cases no part of the images whatsoever. None of these results could be defined as conclusive in determining that the image was manipulated.

“In the 13 different tools used, only one of the results matched the changes claimed by the user,” said Timmi.

A comprehensive guide to the use of such tools is beyond the scope of this article, but this example is a cautionary tale about treating any single such tool as conclusive. In the case of facial recognition tools, for example, Bellingcat always seeks alternative corroborating evidence before making positive identifications.

As Timmi concluded in his analysis of the image, “an analysis of a photo using a single tool is not sufficient by itself to determine a manipulation”.

Timmi Allen contributed to this article