The Data and the Dossier: Validating the "Wagnergate" Operation

Following the arrest of 33 mercenaries in Belarus in July 2020, аnd having early indications that this had been the result of an interrupted Ukrainian lure-and-capture operation, Bellingcat took the decision to begin filming a documentary focusing on the story behind the brazen sting.

In August 2020, Bellingcat then discovered that several top-ranking operatives of Ukraine’s GUR MOU (military intelligence), including its director, had been suspended from their jobs just days after the Minsk arrests.

Unusually for Bellingcat, the Wagnergate investigation relied to a large extent on sources who could not be named either because they requested anonymity to discuss classified matters or, in the case of Russian mercenaries, who requested they not be named for their own safety.

Yet open source techniques still proved crucial in critically analysing what these individuals had stated.

The Former GUR MOU Operatives

Bellingcat approached two of these operatives to request interviews for the prospective film. The officers initially declined, citing legal, national security and moral considerations.

The following few weeks saw a surge in public interest in the abortive sting which Ukrainian media dubbed “Wagnergate”. It was accompanied by multiple conflicting narratives, some of which appeared to be active disinformation measures, both from Russian and from Ukrainian sources.

Russian propaganda channels portrayed the operation as a failed US intelligence false-flag active measure aimed at disrupting the relationship between Belarus and Russia. In the Russian narrative, Ukraine’s role in the sting had been secondary and trivial, and the operation was presented as complete failure.

Ukrainian political parties, for their part, exploited the sting operation for their own ends. The Office of the President and affiliated MPs denied the Ukrainian origin of the operation and alleged it had been a Russian false-flag measure. Opposition parties and affiliated media, without substantiation, claimed that the operation had been actively sabotaged by members of the president’s inner circle.

It was in the midst of this flurry of disinformation in the early fall of 2020 that the suspended intelligence operatives contacted Bellingcat and agreed to discuss details of the operation. During several days of detailed interviews, which were initially just for background due to the legal sensitivity of discussing secret operations, the former operatives provided a play-by-play chronology of the preparatory and active phases of the sting.

Subsequently, following leaks of audio recordings of recruitment calls to Ukrainian media (which had been edited to disguise the voice of “Sergey Petrovich”), we approached these same officers and requested original, unedited copies of the calls in order to verify their authenticity. Similarly, we requested original data files for documents and photographs emailed by the mercenaries in the course of applying for their jobs — many of which had also been leaked to Ukrainian media. We received a large selection of audio files and documents emailed by the mercenaries.

Due to the potential conflict of interest on the part of the suspended officers, the data they provided needed to be critically evaluated and verified.

Validating image and PDF files

Each of the mercenaries’ file collections came in a set of three sub-folders per person: audio, documents and (optional) forms.

The folder Documents contained files – typically scans or photos of documents – sent by the candidate mercenaries. The Forms (бланк) folder contained the person’s filled-in application form for PMC MAR.

All of the sent documents appeared to have retained their original metadata, including creation date and modification date, and in some cases geolocation data.

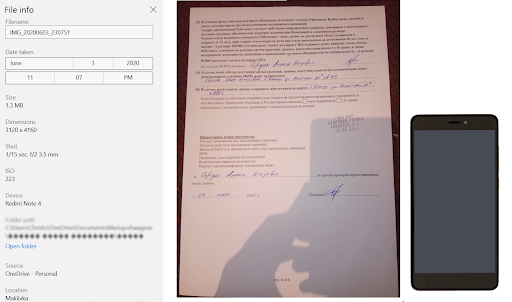

This photograph of an application form was taken with a Redmi Note 4, according to the file metadata. The phone’s silhouette is visible in the shadow on the sheet, and has identical dimensions and angle curves with a Redmi Note 4 (right). The file name is consistent with a photograph taken on 3 June 2020, and the metadata shows the same date. The same date is also written on the signature page of the application. The geolocation date shows “Makiivka”, a town 10 kilometres from Donetsk in Eastern Ukraine where the photograph was taken. The address listed in his application is in Donetsk, and in a call between “Shaman” and “Sergey Petrovich”, it becomes clear that the mercenary resides in Makiivka. These data points provide a rare case of holistic, mutually corroborating validation of the authenticity of the data on this mercenary.

While not all mercenary files contained enough data points for such comprehensive validation, there were no cases of conflicting or demonstrably inauthentic data in the files reviewed by Bellingcat. This includes the documents with the more newsworthy claims, which would be the most likely documents to be tampered with.

Verifying audio (call) files

The archive we received contained 236 audio files pertaining to 72 different mercenaries. This sample included approximately 40 percent of all those who sent their details to the fake military contractor — and included all of those arrested in Minsk by Belarusian security services.

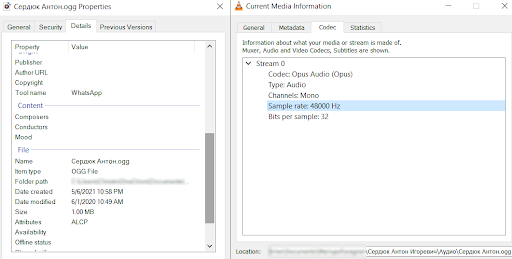

The audio files were in the ogg (container) format, and a few were in the mp3 format. The ogg files were in fact opus-encoded audio files in the format typically recorded by the WhatsApp application and in the ogg container which results in a download via WhatsApp Web.

The ogg audio files had limited metadata, but what they did contain confirms that they were created by WhatsApp. The sound characteristics of the recorded audio show that “Sergey Petrovich” was recorded in full vocal bandwidth directly by a microphone near him, while the counterpart is heard via the limited bandwidth of a phone line, then relayed via a speakerphone. Thus, the audio was not recorded on the phone from which the calls were made, but on a different device in the same room as “Sergey Petrovich” — possibly a voice notes app on another phone, or even directly as WhatsApp voice notes on the other phone. The encoding into the WhatsApp format was not done on the same day as the calls were made; in fact many calls have a modification date of 1 June 2020, which could be explained by the fact they were all sent and received from the original recording phone via WhatsApp on that day.

Due to the fact the audio files were re-encoded, it is impossible to establish the original recording time. However, there is no evidence of editing, trimming or splicing in the audio of any individual audio recording, and the sequence of calls follows a logical pattern. For example, in the case of calls to “Shaman”, each subsequent (numbered) call flows logically from the previous call.

In order to further validate the authenticity of the calls, Bellingcat also called several phone numbers of mercenaries whose voices were available through the collection of calls. The numbers were identified using services that reveal phone owners from open source data, ranging from aggregating services like GlazBoga, to contact book apps like NumBuster and GetContact, and also messenger services like Telegram. This same technique of using multiple, independent open source databases with user-uploaded content was used to identify many of the FSB officers involved in the 2020 poisoning of Alexey Navalny.

One of the former mercenaries we called — who had been among the detainees in Minsk — agreed to talk to us and share his story, on the condition that we did not use his name. This allowed us to compare his voice to that of the audio calls in the folder bearing his name, and the voices and intonation characteristics were identical. An exhaustive and more technically specialised voice comparison was considered unnecessary in light of the fact that the man also confirmed that he had had three phone calls with the person he believed to be “Sergey Petrovich”.

Validating the narrative

A large part of the operatives’ version of events was validated through the verified phone calls and document collection. Another part could be verified using objective open source data.

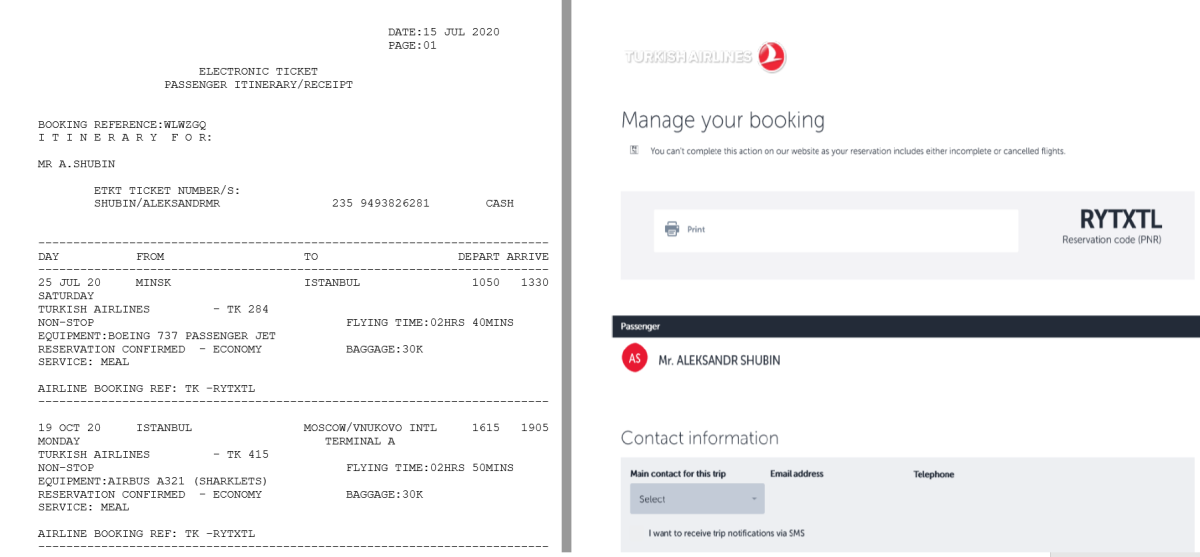

For instance, their narrative about the rebooking of the plane tickets of the mercenaries — initially for 25 July, and then for 30 July 2020 — could be validated by Turkish Airlines’ online booking management system. Electronic tickets provided to us by the operatives included reservation codes, which any customer receives upon making a booking. This allowed for a simple check against the online Turkish Airlines database — and in each case they pulled up the person’s full name. By extension, this validated the booking date (15 July 2020 in the case with the early tickets, and 24 July in the case of the tickets rebooked for 30 July) thereby confirming one more datapoint in the timeline suggested by the operatives.

A screen grab of flight information compared with that found on the Turkish Airlines online booking tool.

Other parts of the operatives’ narrative could be validated against the narratives of the interviewed mercenaries. Independently of one another, they described unprompted the same overall course of events starting from recruitment calls, the death of “Sergey Petrovich”, the change of destinations from Syria and Lebanon to Venezuela, the circumstances of the trip to Minsk including the border crossing hiccup, the rebooking of the flights, and their ultimate detention in Minsk.

The only parts of the operatives’ narrative that could not be independently validated related to the meetings they described that allegedly took place with the office of the president relating to the decision to delay the operation. We have not received a denial or a confirmation from the office of the Ukrainian president to questions about the related events despite multiple requests for comment.

Vasily Burba

Vasily Burba, the former director of GUR MOU, declined to answer Bellingcat’s questions related to the operational details of the sting operation. However he confirmed the information initially provided to Bellingcat by the two former GUR MOU operatives about the exchanges he had had at the Office of the President in particular in relation to the delay of the operation. As the only other two witnesses of the alleged discussion were the head of the Office of the President and Ruslan Baranetsky, and neither agreed to be interviewed, Burba was the only source of this particular information. This data was only confirmed by his two former employees who stated they received update phone calls from him right after the alleged meetings.

The Interviewed Mercenaries

Bellingcat reached out to one of the men detained in Minsk, as outlined above, who became a willing interviewee for this investigation. He agreed to an (anonymised) video interview in Moscow as well as more than 10 follow-up telephone interviews that were required to fully clarify the details provided. He also shared documents including electronic tickets and charging papers from Belarusian police and prosecutors.

This individual introduced us to a second person from the mercenary group. However, this person was less forthcoming and made a significantly smaller contribution to the overall investigation, providing only one interview which was mostly focused on Wagner’s history of military operations. A third member, who the first contact brought for a video interview, got cold feet before going in front of the camera and was not questioned.

The motivation of this source to speak to Bellingcat is not fully clear. It can be partly explained by his desire to set the record straight on some errors in previous reporting on the topic (i.e. not all of the captured mercenaries had served at the Wagner PMC, nor had all of them participated in fighting in Donbas). He also described being disillusioned with the Wagner PMC and wished to share his experiences. It cannot be discounted that his motivation may have been aligned with Russia’s propaganda interests. By mid-August 2020, Russian authorities were openly promoting the narrative that the mercenaries had fallen for a foreign sting operation, with Russian state-run media running interviews with some of the detained mercenaries. The Kremlin’s position appeared to acknowledge the counter-intelligence failure but to minimise the value of the intelligence passed on to Ukrainian secret services, and to attribute the sting operation to US intelligence.

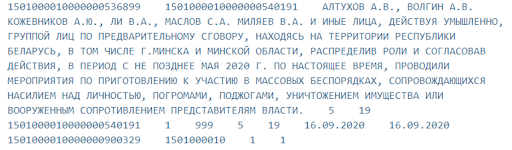

These possible ulterior motives were taken into account when validating the evidence obtained from the interviewed mercenary. The description of chronology of events and documents he provided appeared consistent with those obtained through the Ukrainian operatives’ testimonies and phone calls. Moreover, the electronic tickets provided were validated through the Turkish Airlines booking management tool. The police charging documents could be validated through the Cyber Partisans hacktivists group who had obtained access to Belarusian police databases and were able to independently extract a charging summary with identical wording.

Yet this source’s testimony appeared questionable in its assessment of the value of intelligence passed on to Ukraine, both by him and by the other mercenaries, as well as in his assessment of the professionalism of Ukrainian special services in the context of the sting. He described only one phone call with “Sergey Petrovich” which contained no sensitive data about his prior military service activities. However, the four phone calls obtained by Bellingcat contain material disclosures including about the role of the FSB as his kurator while stationed in Eastern Ukraine in 2014.

He further disparaged the achievement of Ukrainian secret services in luring the mercenaries out of Russia by attributing it to a coincidence: another, authentic recruitment process of security personnel needed by Rosneft in Venezuela had been going on at the same time. Russian security services had mistakenly assumed that the Ukrainian operation was part of that legitimate recruitment process, thus — in his words — Ukraine’s success in luring them was a stroke of luck.

The source also claimed that almost none of the mercenaries had real combat experience nor had committed crimes in the Donbas, and that many of them had inflated their military achievements to increase chances of being recruited. This however is contradicted by both data provided by the applicants (including reference letters from their superiors and medals), and by independently obtained data on their role in Eastern Ukraine.

Despite this the source’s contributions proved valuable as they provided documentary validation of the narrative of the operatives. It also shed light on the previously unknown fact that the Russian security services kept the mercenaries in quarantine for two weeks after repatriation, during which they questioned them to try to piece together the full background of the Ukrainian sting operation.

Intelligence sources providing data to the Parliamentary Commission

In the two weeks prior to the publication of the interim report of the Ukrainian Parliament’s Ad-Hoc Inquest Commission, dealing partly with the same subject matter, Bellingcat was asked to verify certain declassified intelligence data provided to the Commission. The two data points represented presumed evidence that Russian and/or Belarussian security services had knowledge of, or had infiltrated the Ukrainian sting operation.

Data point one

In the first of these instances, declassified data suggested that several mercenaries (who did not ultimately travel as part of the first group) had contacted Russia’s Federal Security Services (FSB) in May 2020, and subsequently Russian Military Intelligence (GRU), disclosing details about the ongoing recruitment and expressing doubt about its legality.

This claim couldt be neither verified nor refuted, as it was based on mostly classified intelligence data that was not made available. However, the narrative that one or more of the recruits reached out to security services is consistent with the version of events described by the former operatives who described an incident of one dissatisfied recruit threatening to complain to the FSB. According to the operatives’ narrative, this did not lead to any active intervention by the Russian security services, partly thanks to the (former) GRU asset who had been compromised by Ukraine and served as a person of reference for the legitimacy of the project.

Some other early candidates dropped out of the recruitment process despite being approved, including the high-value target Dmitry Grigoryan, and Igor Tarakanov who had already been scheduled to fly as part of the initial group. It is possible that they dropped out because they had suspicions about the legitimacy or safety of the recruitment operation.

The interviewed mercenary also said that he contacted – like others potentially did too – contacted his FSB “handler” to ask about the legitimacy of the recruitment project, and was told that it is legitimate. In his view, this was the result of a very similar legitimate recruitment project for security services to Rosneft in Venezuela at the same time which led to confusion among FSB counterintelligence circles.

No evidence of proactive measures by Russian security services to combat the operation were discovered by Bellingcat, nor was any contained in the declassified portion of the intelligence shared with the Commission.

Data point two

The second datapoint related to possible infiltration of the sting operation by Belarussian security services. The declassified evidence for this argument included the alleged true identity of the mercenary having a Belarusian passport, and alleged that he was an agent working under cover identity for Belarusian secret services.

Bellingcat, using data provided by Belarusian Cyber Partisans, found this allegation to be untrue and informed the Ad-Hoc Interim Commission which took this into account in its report.

Other unattributed leaks

In the course of the investigation, Bellingcat analysed documents leaked to Ukrainian and Russian media that were mostly verified as authentic.

However, there were also purportedly leaked documents that reached Bellingcat via various channels, which were proven to be inauthentic.

In one case, the subject matter and data suggests that the inauthentic document may have been sourced from a Ukrainian intelligence agency, as it partly overlapped with one of the data points provided to the Ad Hoc Commission by Ukraine’s intelligence community (an alternative explanation might be that the same unreliable source provided data to Ukraine’s intelligence community)

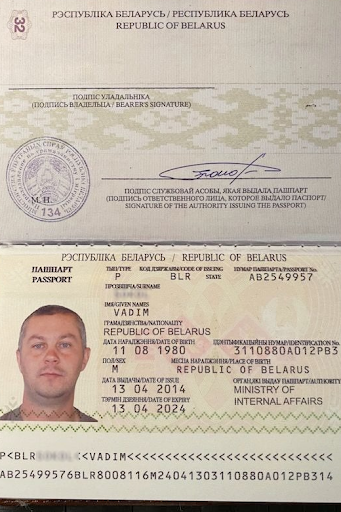

This anonymous leak included purported evidence that the Belarusian member of the mercenary group, Аndrey Bakunovich, was in fact a different person, and provided the name of that person (Bellingcat does not disclose that other name as it belongs to a real unrelated person). In this hypothesis, Bakunovich was a fake identity.

Moreover, the source passed on a purported photograph of the alleged person.

This “leak” was proven as a fake based on data obtained from hacktivist group Cyber Partisans. A comprehensive review of all Belarusian identities named Vadim S. showed that the person indicated in the intelligence report exists but is a different person. Furthermore, according to Cyber Partisans, the personal ID number contained in the passport not only did not exist in the centralised citizen database but also did not match the rules governing the creation of ID numbers in Belarus.

Lastly, the photo on this purported passport matched the photograph of a different known mercenary, Pavel Samarin. It is not clear what the motivation for this inauthentic leak was, and how and why it may have reached Ukraine’s military intelligence.