Ghost In The Machine: From Chad, A Case Study On Why You Shouldn’t Blindly Trust Tech

Researchers analyzing current or past events are at constant peril of misinterpreting data, leading to conclusions that are either skewed or plain incorrect. This is particularly true in the field of open source investigations, where methods for research and verification are often experimental, which in turn can make it hard to cross-reference data with high-confidence information.

This case study will detail how even rigorous open source research can fall prey to unforeseen error — and what approaches will mitigate such risks for investigators.

The Boma Attack

On March 24, 2020, news began to circulate that an attack on Chadian troops in the Lake Chad Basin had claimed at least 92 soldiers’ lives. Subsequent reporting, particularly by European news outlets, dated the incident to March 23.

The attack was immediately attributed by local media — as well as the Chadian government — to a generic “Boko Haram,” although several commentaries linked it to the minority faction of the Jamaat Ahlussunnah lid-Dawa wal-Jihad (JAS), a splinter group created in 2016. This group is led by Bakura Doron in loyalty to the infamous Abubakar Shekau, and in competition with the ISIS-affiliated Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP).

The attack reportedly happened in the village of Boma, otherwise known as Bohoma, a settlement “completely surrounded by the waters of Lake Chad”, where “it had been thought back in the day of placing a military unit” as a protection measure. According to the same source, however, “in recent times, that unit was partially removed for operational needs elsewhere,” as stated by the President of Chad, Idriss Déby Itno, during his visit to the attack’s location.

Identifying The Location

Navigating the complex, sparsely documented, and constantly shifting geography of the Lake Chad Basin is often difficult. Still, public reporting again offers clues as to where the site of the attack could be located. For example, one report by RFI, posted on March 25, points to the “nearby village of Kaïga Kindjiria,” which will come up often in the following days as the vantage point selected by President Déby to personally lead the counteroffensive.

Kaïga Kindjiria is easily identifiable on maps as being located at 13°57’50″N, 13°41’47″E. It’s one of the main settlements in the northern sector of the lake, and in the province of Fouli. Approximately 16 km south-east of the village, at 13°50’55″N 13°47’40″E, we find another settlement marked on maps such as OpenStreetMap as “Bohouma.” The similarity with the spelling, as well as the geographical proximity, make it an interesting potential candidate for the site of the “Battle of Boma.”

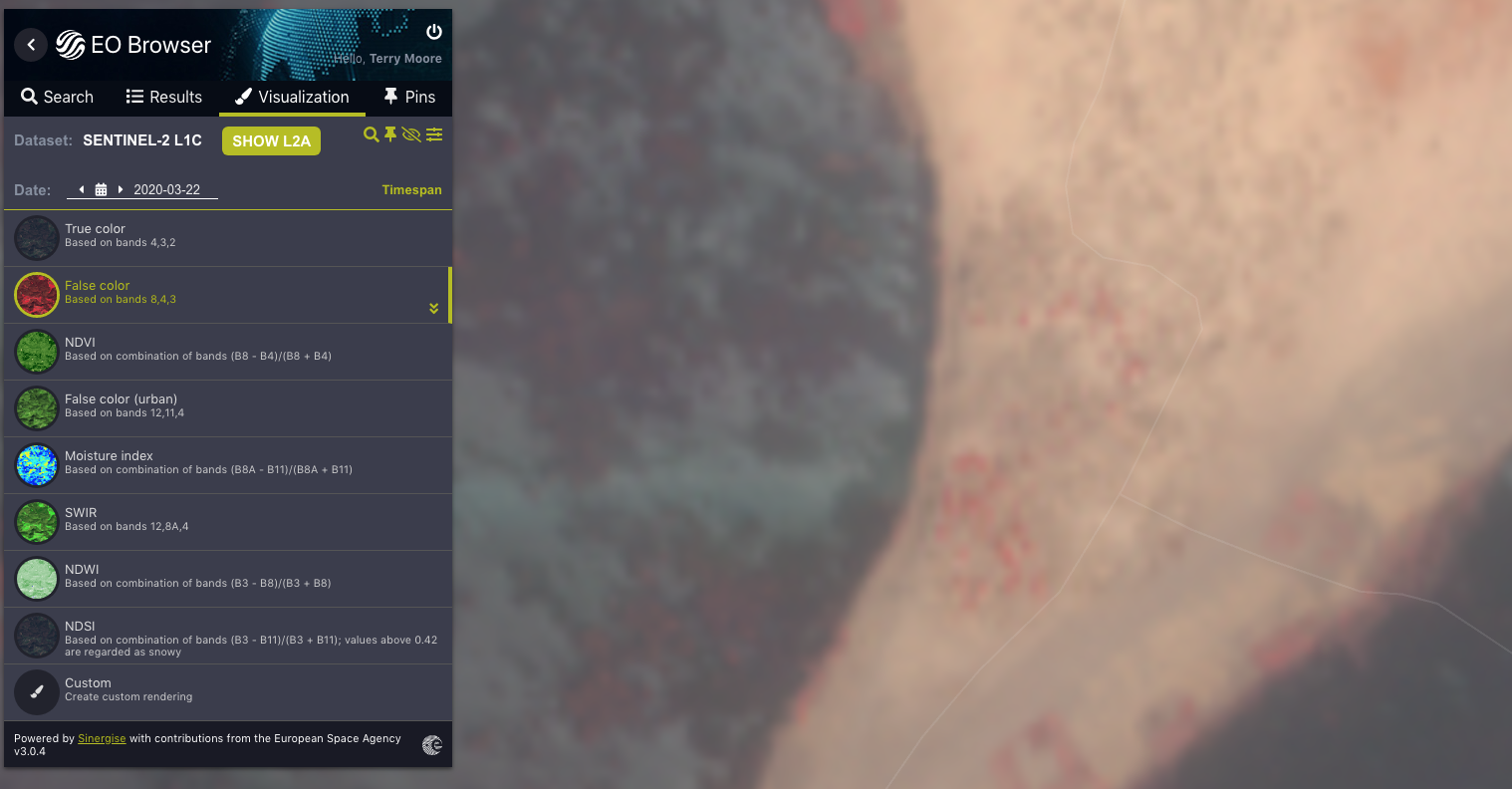

In order to confirm this, we move to another open source satellite imagery provider, SentinelHub. Using its Playground platform, we review the available imagery for the settlement of Bohouma on the dates surrounding March 23.

Only two captures are available for the period of interest and at the required detail. Both captures are made through a Sentinel-2 satellite, which offers some of the best tools for analysis, as we’ll see shortly.

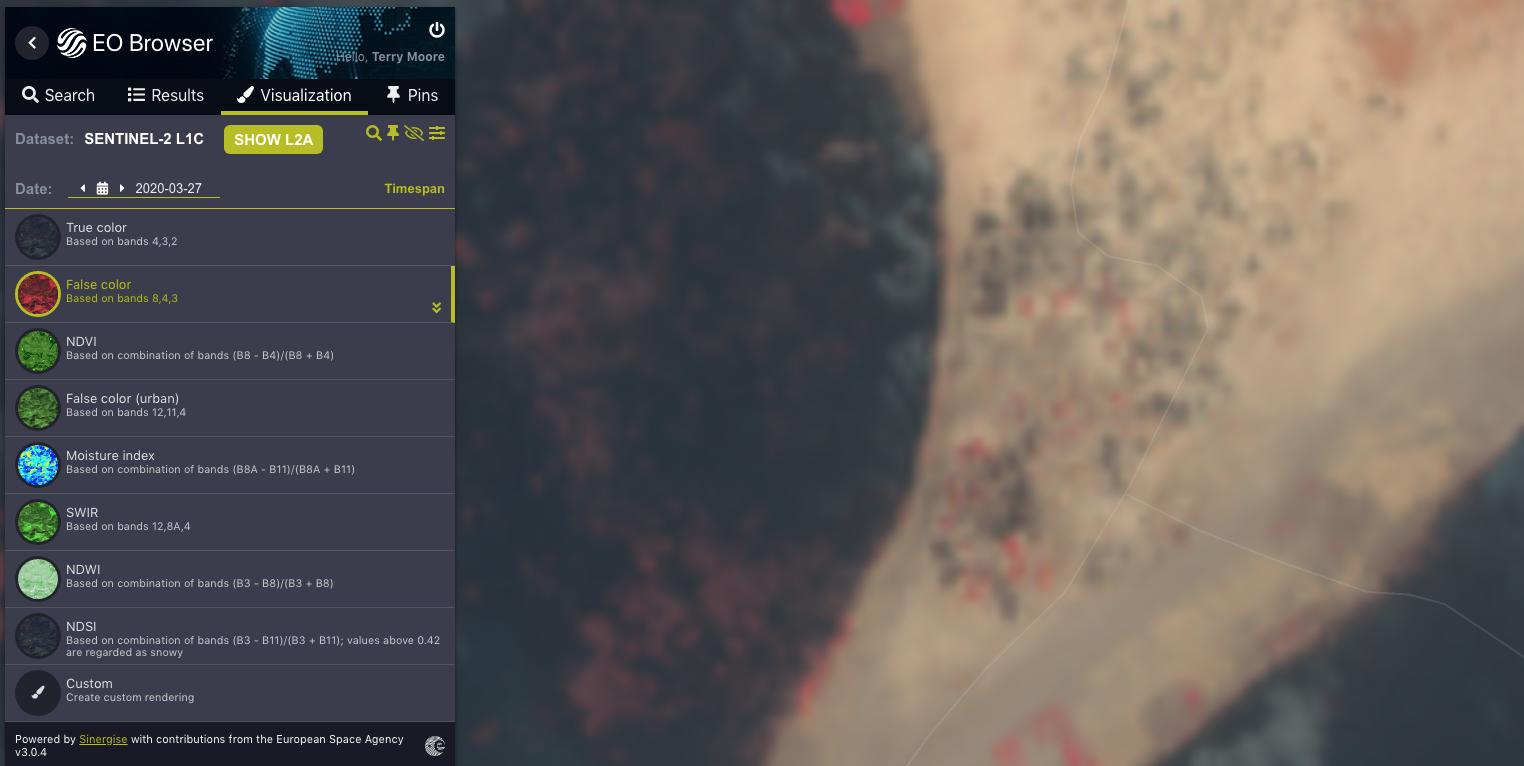

No noteworthy elements appear in the first capture from March 22. Though we can’t be certain because of the limited resolution available, there are land markings consistent with burn damage in Bohouma village in the second capture from March 27, impacting a significant portion (though not the entirety) of the settlement’s area, visible even without adding a layer of false color — a useful method to track potential conflict damage through the variation of the vegetation’s shape and volume, and one that we are deploying here too.

Satellite capture for March 22, showing no damage markings to the village of Bohouma. The red spots are likely vegetation, highlighted through the “false color” module in SentinelHub

Second satellite capture, on March 27: black markings, consistent with burn damage to buildings and huts, appear across the settlement

Investigating The Response: “Wrath Of Boma”

On March 29, President Déby — who came to power in 1990 through a military coup he personally led, and who retains supreme command of the Chadian National Army (ANT in the French acronym) — declared the beginning of operation “Wrath Of Boma” in response to the attack. Paired with the declaration of the state of emergency in two provinces, the forced eviction of the local population from their homes, and their displacement outside of the operation’s area, “Wrath Of Boma” was reportedly led from the mentioned village of Kaïga Kindjiria. There is a trove of video and photo documentation of these events, but most of it is filtered through the lens of the official public broadcaster, Tele Tchad.

On a Tele Tchad report published on March 30, for example, we can observe Déby reviewing the theatre of operations on both a military map and a palmtop while at a makeshift barracks in Kaïga Kindjiria:

Another video, possibly taken on the same occasion, sees him reviewing a map placed on one of the barrack’s walls. Although the map itself was blurred in post-production, the contour of the northern half of Lake Chad is clearly visible:

Tele Tchad’s reports predictably don’t elaborate on how, and where, the operation occurred. The official version, accurately replicated in the video reports, is that from Kaïga Kindjiria, the counterinsurgency effort covered the entire northern area of Lake Chad, including land and waters well beyond Chad’s national borders, and into Niger’s territory. In fact, in a report posted on April 8, the reporter claims to be located 16 km into Nigerien land, alongside an ANT contingent.

Official reports also claim that “numerous Boko Haram hideouts” were identified and destroyed, large caches of weapons were seized, and “1000 Boko Haram fighters” were killed — a number that analysts consider to be largely exaggerated and unrealistic. Déby himself stated “not a single BH fighter still exists” on the Chadian portion of the Basin.

Verifying The Government’s Claims

Given the bold claims made by the Chadian government, we decide to embark on a verification quest. The objective is to determine the scale of the counterinsurgency operation; its tactics; and the plausibility of the results claimed by Déby and the ANT.

Due to the remote location and predictable lack of access to online communications by the local population, verifying the means and scope of “Wrath of Boma” through social media content is difficult. While expressions of support, as well as criticism, aren’t rare in the Chadian online communities, posters rarely have access to firsthand imagery. When imagery was present, it mainly included the return of ANT troops to the capital, N’Djamena, at the end of the operation, and didn’t illustrate their previous actions in any way.

The most promising research path, once again, seems to be through satellite imagery.

We start by deriving an important clue from one of the news reports available online. A video published by the independent African news portal AfricaNews on April 11, three days after the purported end of the “Wrath” operation, shows aerial views of unidentified islands in the Lake Chad Basin, presumably taken from a military aircraft or helicopter. We can see the shoreline of one shown island as being on fire:

It therefore appears that the ANT was setting at least portions of the Basin’s islands on fire, presumably to drive fighters out of their hideouts in the bushes. Given the Basin’s morphology and vegetation type, this would not be surprising — it would also be consistent with what the Nigerian Air Force has been historically known to do. A salient example is the Sambisa Forest area and how it was treated during their own years-long counterinsurgency operation Lafiya Dole.

How extensive was the application of this drastic measure? How much of it targeted specific locations of alleged BH bases, versus the entire area indiscriminately?

Spotting The Error

Selecting The Right Tool

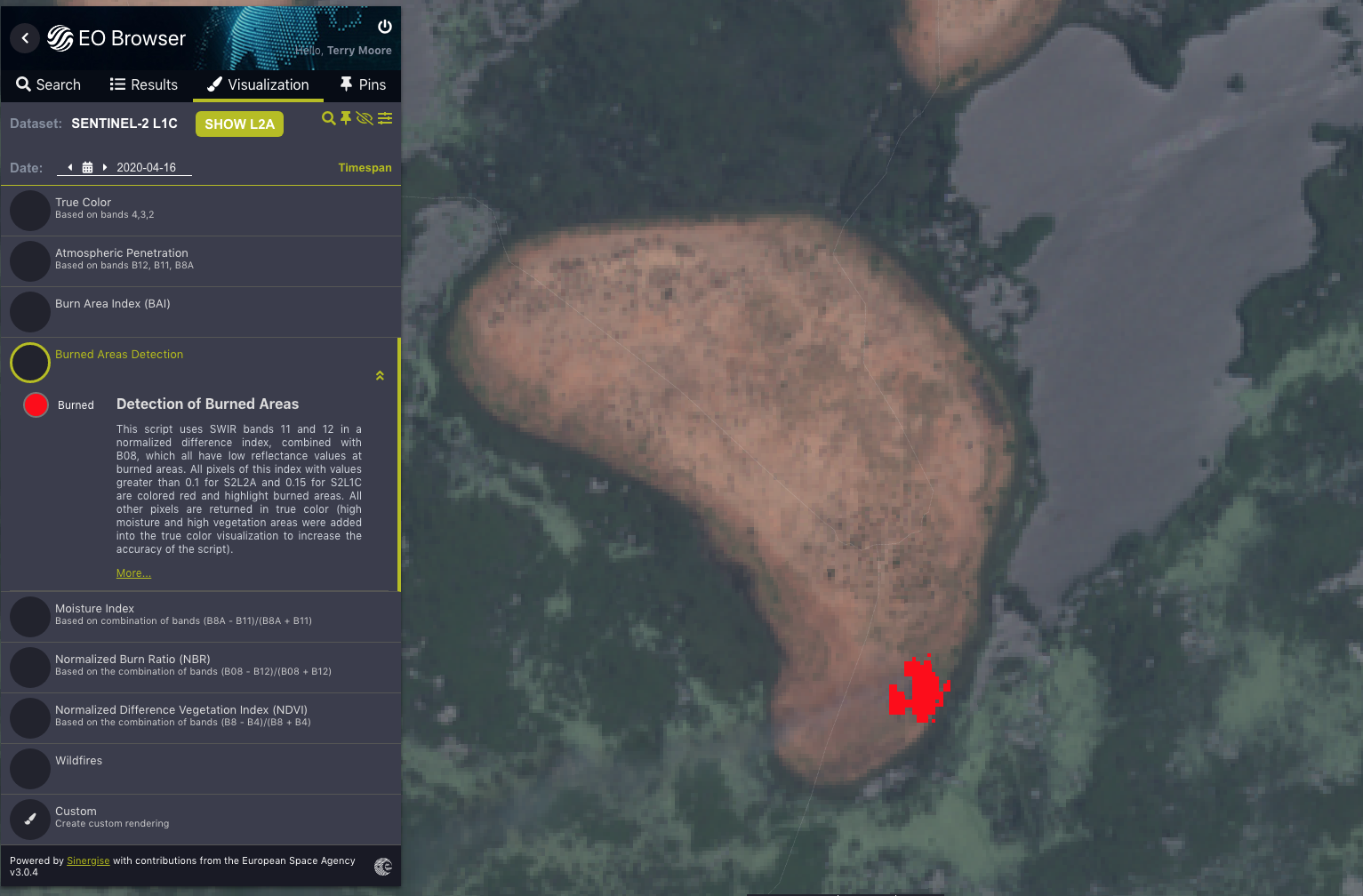

Given the available clues on the ANT possibly utilizing extensive fires as one of their main counterinsurgency tactics, we then decide to utilize the powerful capabilities SentinelHub has in this specific space to obtain a better understanding of the scope of “Wrath Of Boma”.

First off, we need to:

- Switch to the EO Browser, the SentinelHub environment allowing for the use of scripts;

- Change the satellite to Sentinel-2;

- Change the theme to “Wildfires”;

- Change the map’s layout to Burned Area Detection. This is a custom script that uses a specific series of frequency bands to analyze vegetation and soil moisture in order to detect areas that are likely burned. A complete description can be found here.

With that layout set, we run the search for imagery again throughout the first week of April, the approximate period for “Wrath Of Boma”. While not much of relevance appears before April 8, when the government declared the operation complete, on April 11 the map lights up with a large number of Burned Area events over the northern sector of Lake Chad:

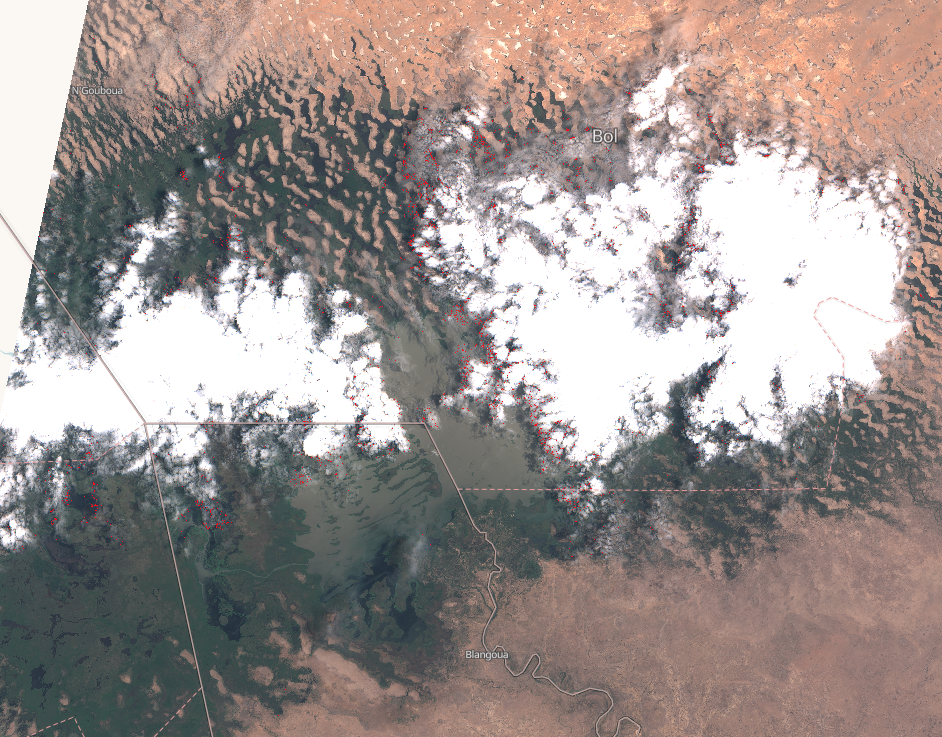

By zooming out and reviewing an even broader area, we see that Burned Area events appear over the entire northern quadrant of the Lake Chad Basin, for an estimated area of 3000 square km (and well into Niger):

What at first glance appears to be a large cloud formation hovering over the Sahel region seems now quite possibly, either partially or in its entirety, the product of thousands of kilometers of shorelines and vegetation burning.

This is what we are thinking at this point: Could it be that the Chadian government decided (and managed) to set the entire northern area of the Lake Chad Basin on fire?

To confirm that what we are looking at are, in fact, fires, it’s useful to zoom in on the islands in the impacted quadrant. Taking as an example the tiny, nameless island located at 13°53’21″N, 13°41’48″E, we can observe Burned Area Detection highlighting a part of its southern tip:

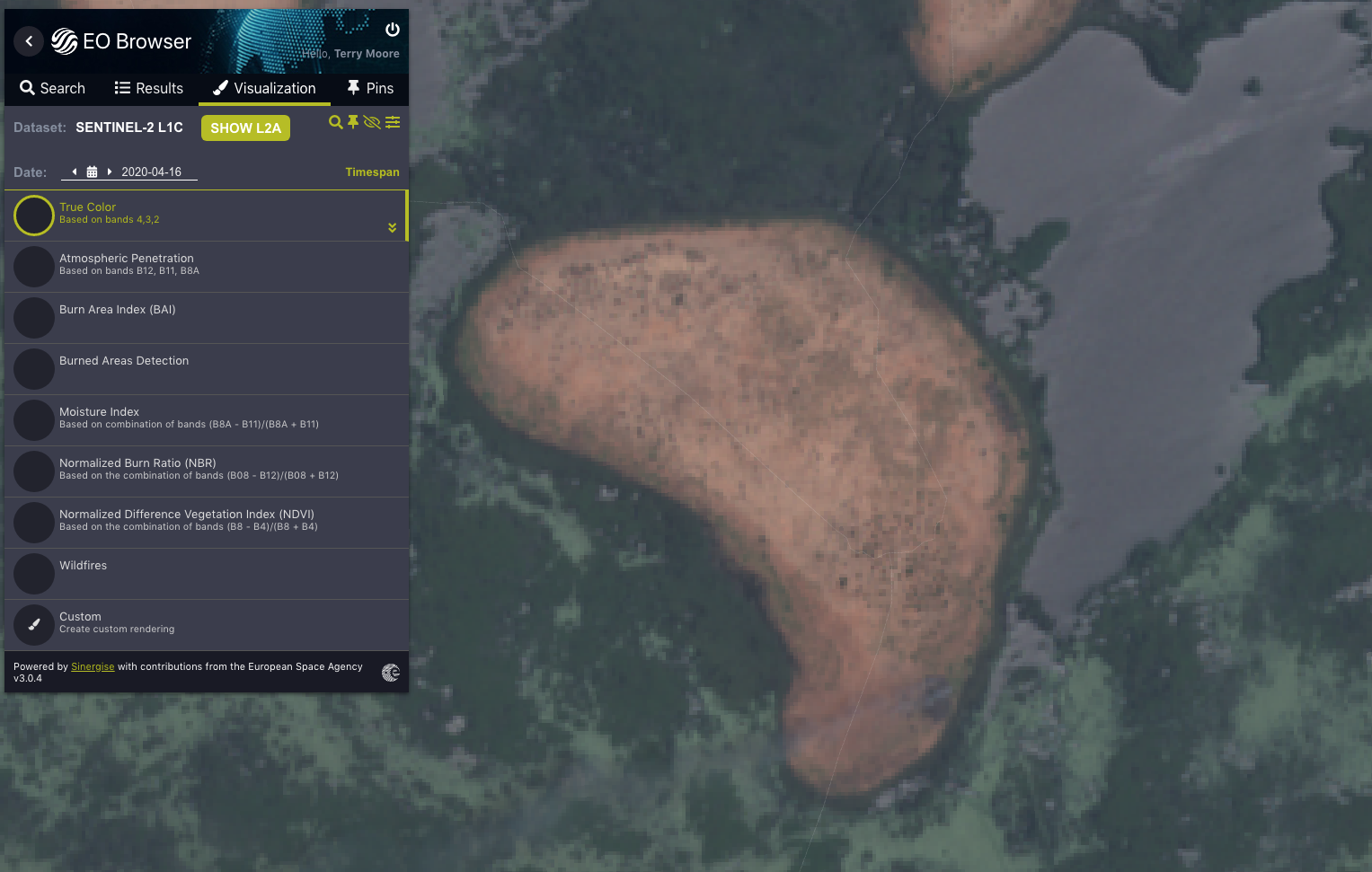

By reverting to the True Color layout, we can clearly identify the burn damage marking on the ground, as well as the plume of smoke rising from it:

A quick check on higher resolution public imagery, such as Bing Maps (using DigitalGlobe imagery) shows the presence of a settlement in the vicinity of the fire, and it’s possible that the fire itself had effectively hit an insurgent hideout hidden in the bushes, if not underground.

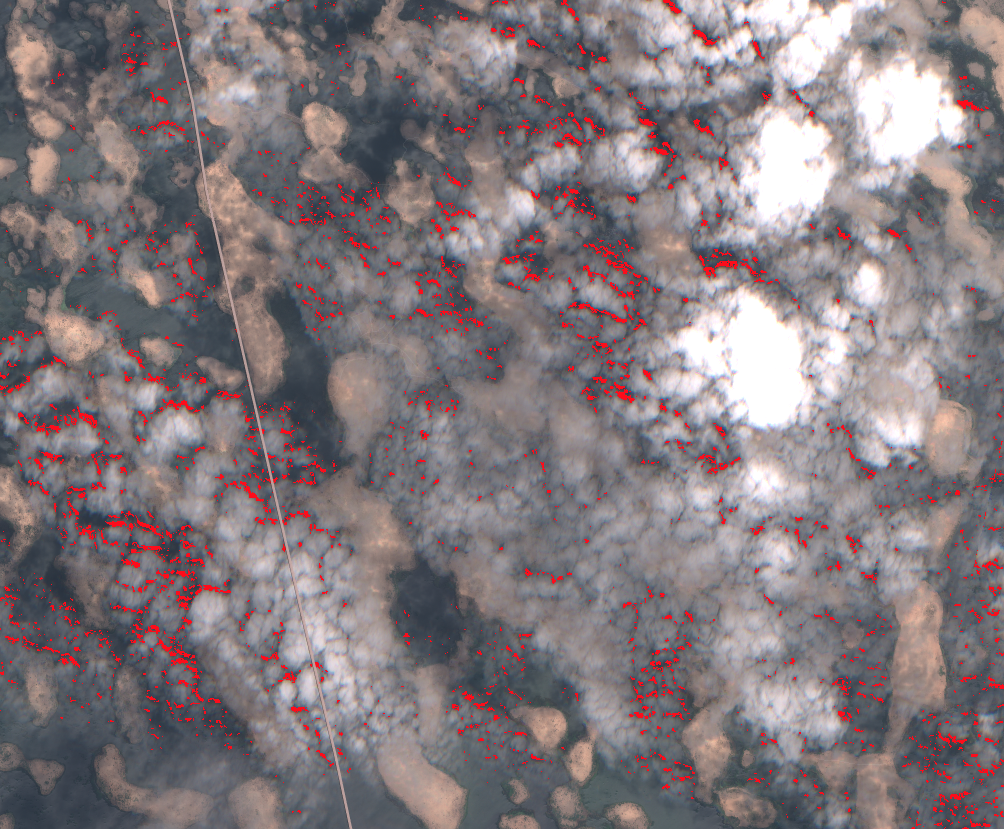

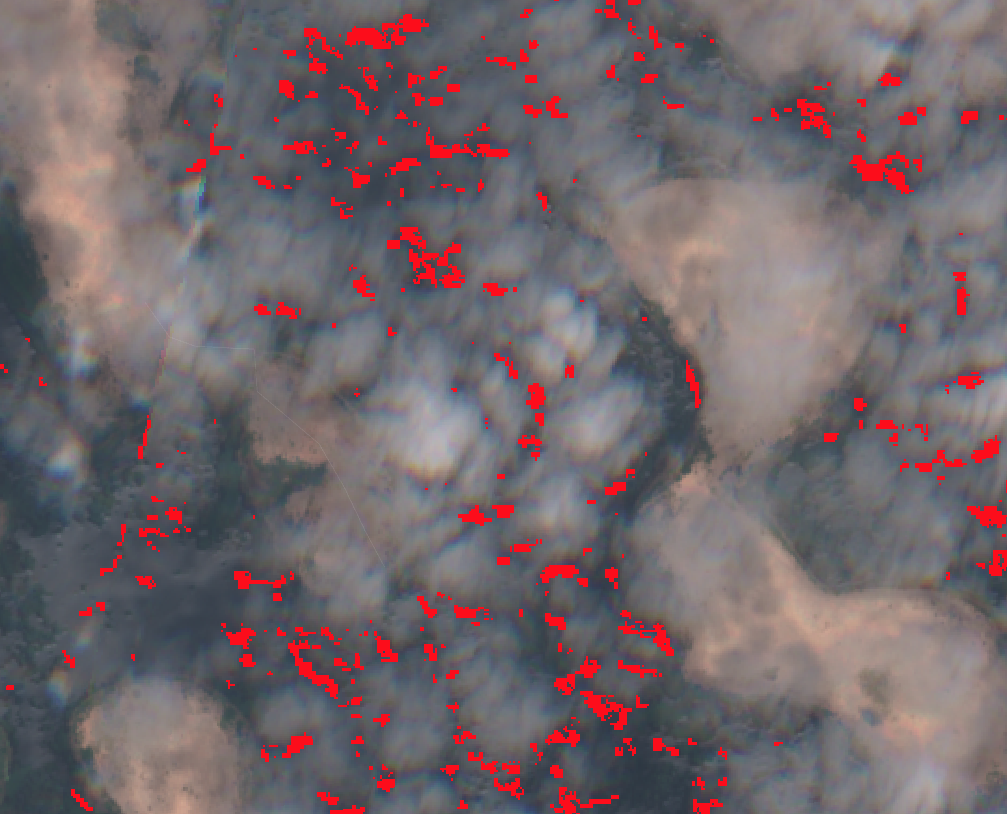

When the script-highlighted areas for April 11 are inspected closely, it becomes clear that the vast majority of them are positioned over water.

Lake Chad is a mostly shallow, marshy body of water, where vegetation can be seen at surface level (and in satellite imagery). Canoes and speedboats are the only means of transportation able to navigate it. The images for April 11 appear to show that burning areas were, for the vast majority, over waters.

At this point, we have a working theory that the surface vegetation over the northern portion of the lake was set on fire indiscriminately, perhaps through the use of fuel, or other fire accelerant.

Satellite imagery at different resolution levels showing the burned area events as overlapping waters, rather than land

The situation appears even more interesting when we look at imagery for the following days, when the script’s results suggest that the operation was becoming more targeted. On April 13, for example, the Burned Area Detection script shows the highlighted areas as moving towards the eastern side of the lake:

On April 16, only a few spots remain marked as probable burned areas, at least in the north-east area of the lake.They appear mostly over land this time, and can be manually verified as possible hiding places for actual fighters. One example is shown in the following captures, taken at 14°09’35″N, 13°30’33″E:

Close-up capture of the same location on undated Bing Maps/DigitalGlobe imagery, showing the presence of a possible hideout in the island’s bushes in correspondence with the burned area, as well as of a trail leading to it (from east to west)

The Cognitive Trap

With SentinelHub’s results in our hands, consistently showing traces of fires during (or sufficiently close to) the dates of the Chadian counterinsurgency operation, and with our manual spot-checks apparently verifying the presence and targets of those fires, our working theory appears to be confirmed. Chad’s Armed Forces seem to have applied a “scorched earth” (or rather, scorched waters) tactic to an area of thousands of square miles, potentially devastating the ecosystem of a large portion of Lake Chad, and therefore annihilating the livelihoods of the resident populations in the process.

However, not challenging one’s own conclusions, especially when their implications are so significant, is usually unwise — and a common pitfall that trained analysts are taught to prevent.

First off, it is sensible to run a check of the SentinelHub’s Burned Area Detection script over the same areas of Lake Chad, but on different dates, when extensive military activity was not reported. We quite quickly realize that the script returns positive results, once again predominantly over water.

As by the end of May we don’t have reports on the Chadian counterinsurgency operation being still active, it’s hard to consider the results as representing actual fires, particularly in connection with a military operation.

We then decide to take a few extra verification steps. First off, we move to a different satellite imagery provider with capability to detect wildfires: NASA’s Worldview. The “Fires & Thermal Anomalies” overlay for April 11 does not detect any probable fire events over the entire Lake Chad region:

That is in contrast with fire events spotted by the tool elsewhere on the same day. For example, in neighboring Nigeria:

At this point, to confirm why we could possibly have obtained misleading results via SentinelHub, we consult with their staff.

The following is a possible explanation the staff provided (warning: tech speak ahead):

“[The] script uses bands 11 and 12 in a normalized difference index, as these bands are used for heat detection. Additionally, B08 is used to make the result even more reliable, as B08 has low values on these areas. Then, vegetation index is used to avoid vegetated areas and NDWI is used to mask water areas. Based on differences in water color, the result of mapping water by NDWI varies.”

[…]

“NDWI fail[s] to classify water areas where water is completely black. Burned areas are usually also very dark and the script gets confused.”

In essence: the script’s detection of burned areas is often tricked by particularly dark waters, such as those that Lake Chad shows to the satellite — being shallow, marshy, and often covered by algae or other vegetation.

Additionally, the presence of clouds could have led the script to further overestimate the presence of burned areas. In fact, a spot check of the cloudy Lake Chad in July shows a number of clearly overestimated pixels, while on a clear day there is no overestimation.

Whatever the reason, the script’s error — in unfortunate coincidence with the individually verifiable burned areas — fed our confirmation bias: It made us see what we wanted to see.

Verification Work Remains Critical Nevertheless

Being misled by erroneous data or information collection challenges shouldn’t discourage researchers from continuing to improve the understanding of the events surrounding massive “counterinsurgency” operations such as “Wrath Of Boma”.

In this specific context, the islands of Lake Chad, mainly populated by peaceful fishermen and farmers belonging to various ethnic groups (most notably, the Buduma), have been historically disproportionately affected by both ISWAP and JAS actions, and by the different counterinsurgency waves enacted by the Chadian, Nigerien, and Nigerian armed forces.

According to ReliefWeb, “the Lake Chad crisis that began in 2015 caused massive displacement in Chad and resulted in close to 100,000 people fleeing their insular or island villages to the mainland.” As of mid 2018, “the context of the crisis has evolved in the southern area of the lake, and significant waves of internally displaced people (IDP) have left the displacement sites and host villages to go back to the islands.”

The ANT unit attacked by JAS in Bohoma — with the massacre there having originated the counterinsurgency operation — was purportedly deployed to protect the civilian population in one of the main settlements for the archipelago. However, as an expert of the Lake Chad Basin region, Marc-Antoine de Montclos, states to the French newspaper La Croix, “during the wars conducted by the armies of the Sahel against the jihadists, the civilians are usually those who pay the highest price. The Chadian army has intervened in an area that isn’t only inhabited by fighters. There are also, for example, many breeders who negotiate their passage with Boko Haram.”

The hyperbolic statements made by President Déby, claiming the killing of “1000 fighters” could be not only exaggerated, but possibly distorted by indiscriminate killing, whether intentional or not, of the islands’ civilian settlers. In fact, continues de Montclos, “in Nigeria, at the morgue in Maiduguri [capital of the Borno state, and epicenter of Nigeria’s fight against the jihadists], the bodies of the people killed during the military operations are given back to their families at the condition that the relatives admit the victims’ status as Boko Haram fighters.”

The influx of Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) likely generated by the state of emergency declared on March 29, and then by the operation itself, is difficult (yet not impossible) to estimate from an open source perspective — the estimate will need data sourced by NGOs operating on the ground and in local IDP camps in the coming months.

Open source investigations, also through remote sensing techniques, should continue to be explored to enrich or corroborate such findings, in the interest of justice for those affected, and accountability for those responsible.