How to Uncover Corruption Using Open Source Research

When most people think about open source research, they think about uncovering social media materials of soldiers on the front-lines of the wars in Ukraine and Syria, or geolocating video footage of significant events with Google Earth. While open source materials have led a mini-revolution in how conflicts are reported online, there is another area where there has been just as much impact: corruption investigations. This guide will provide instructions on how to start doing your own research into corruption using open source materials, and also include advice from experts who have uncovered corruption in eastern Europe, the Balkans, Caucasus, and elsewhere.

Flashing Gold

One of the most obvious ways to find corruption is also the easiest and visually appealing for audiences: comparing the cost of watches and jewelry to declared income. Alexey Navalny and his anti-corruption group FBK famously conducted an investigation into a watch worn by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s press secretary Dmitry Peskov. The watch cost over a $600,000, despite a declared income of a quarter of that.

Часы Пескова заслуживают, чтобы о них узнали в стране, где 23% граждан в категории "бедные" https://t.co/MljfeZUdjD pic.twitter.com/hG8Vy1g956

— Alexey Navalny (@navalny) August 2, 2015

FBK parlayed this research into a cooperative piece with Max Seddon at Buzzfeed News highlighting the cost of jewelry and watches worn by members of Russian legislators and officials. In most cases, the jewelry would have taken a significant percentage of their yearly salaries to pay for.

More on the assets worn by politicians indicating corruption:

- Buzzfeed News/FBK: New Investigation Exposes Glam Life Of Vladimir Putin’s Bling Ring

- The Telegraph: Chinese blogger points to luxury watches as sign of corruption

- MSNBC: Hey, is that a Rolex you’re wearing? How to spot a corrupt politician

- New York Times: $30,000 Watch Vanishes Up Church Leader’s Sleeve

Rich Kids of Instagram

A common trend with corrupt officials is that they will rarely flaunt their ill-gotten wealth, in comparison to their children, spouse, or close friends. Thus, browsing the open source materials related to these people close to a potentially corrupt official gives researchers the opportunity to find evidence of undeclared income and property, such as houses, vehicles, and lavish vacations.

You may be familiar with the Instagram account “Rich Kids of Instagram,” which shows the extravagant wealth of the children of the 1%–or, in most cases, 1% of the 1%. There are equivalent accounts showing the wealth of the children of businessmen and politicians of many countries, such as “Rich Russian Kids,” “Rich Kids of Azerbaijan,” “Rich Kids of Kazakhstan,” and so on. The vast majority of these photographs and kids will not bear any fruit for meaningful corruption investigations, but in some cases, there could be links that work back to a politician, judge, or other government official whose declared income is incongruous with the assets flaunted by their children.

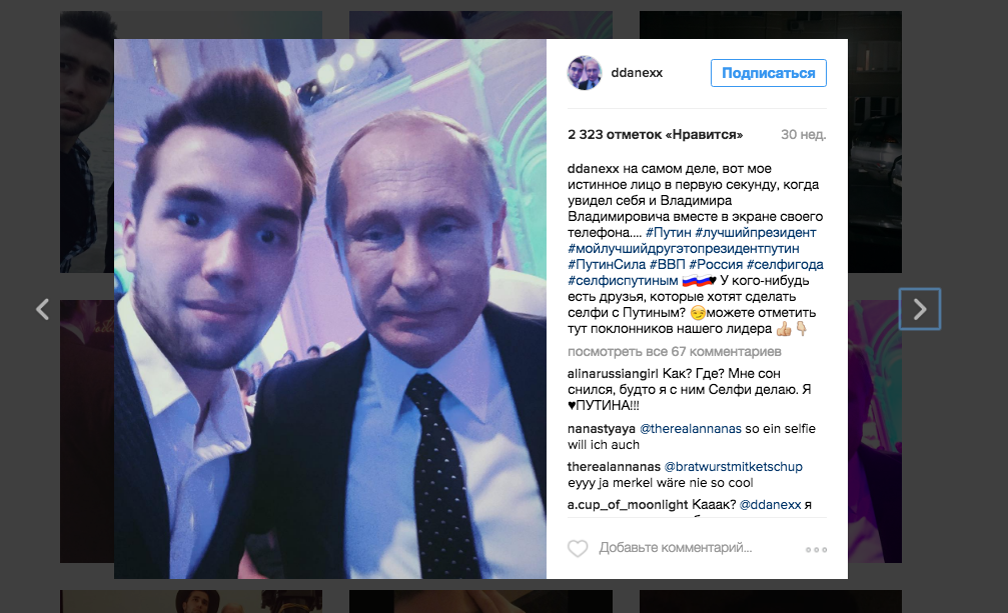

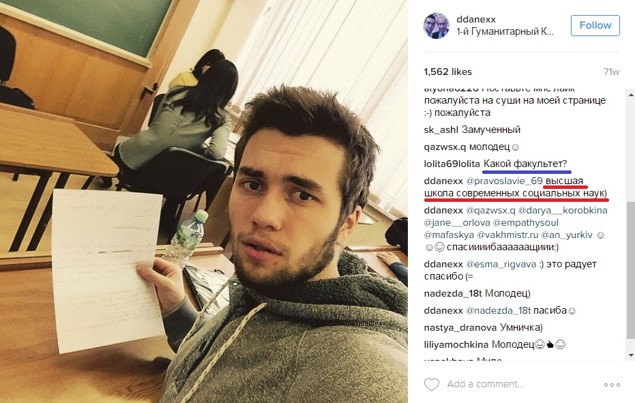

Diana Munasipova and Anna Shamanska of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty followed leads from “Rich Russian Kids,” finding photographs of a 2013 Camaro from the Instagram user “ddanexx” (account has become private since the investigation). Today, if you buy a used 2013 Camaro in Moscow, it would run you at least $30,000.

The interior posted by “ddanexx” matches that of a 2013 Camaro.

The interior of a 2013 Chevrolet Camaro, matching the photograph posted on Instagram.

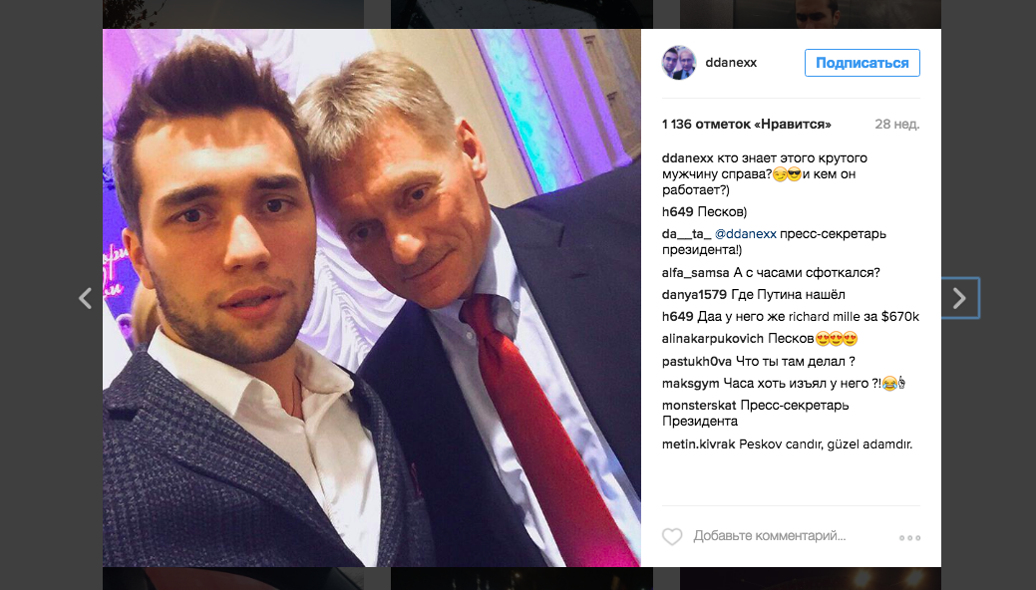

This Instagram user was not just a “Rich Kid of Instagram,” but also one whose father clearly had connections to high levels of governments, judging by the people he posted selfies with, including Putin and his press secretary Dmitry Peskov. This photograph also appeared on “Rich Russians Kids.” Unfortunately, Peskov’s watch is not visible in the selfie.

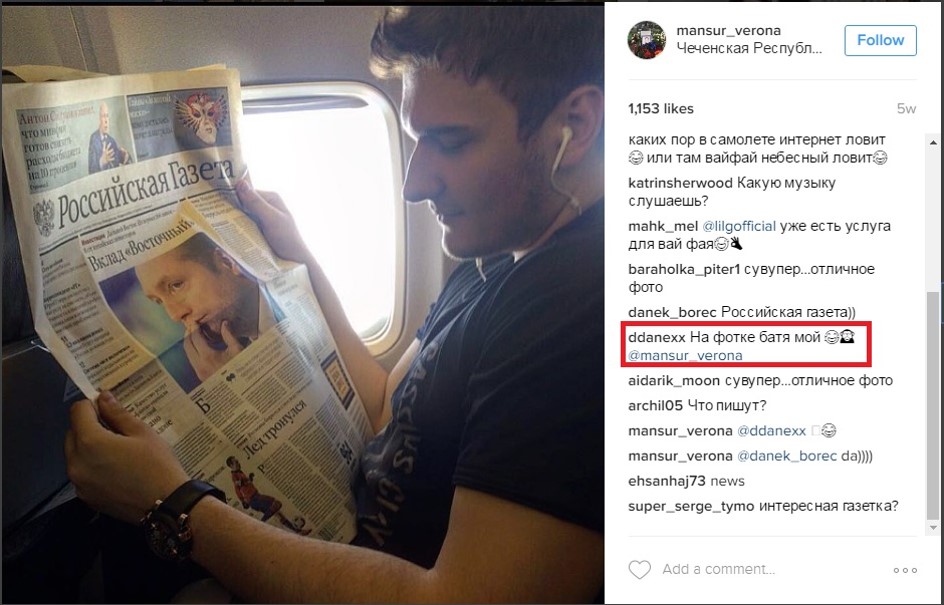

However, “ddanexx” does not publicly share his identity or who his influential parent is. After some more digging, Diana and Anna found that he did reveal these identities in a comment on a friend’s Instagram account. In a picture of a friend looking at a newspaper, “ddanexx” replies that his dad is in the photograph.

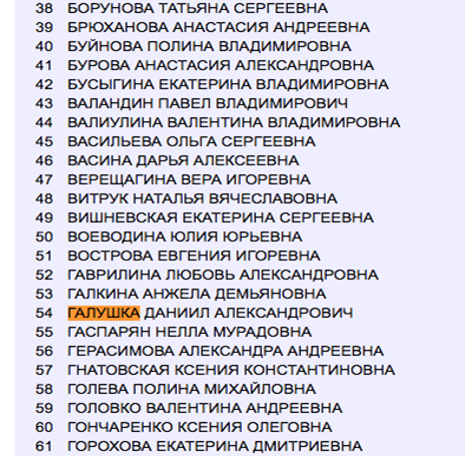

The man on the front page of the newspaper is Aleksandr Galushka, the Minister for the Development of the Russian Far East. Combining this with the information from “ddanexx” account–including his likely first name, Daniel/Daniil, and that he is a student at Moscow State University in the Social Sciences Department–leads us to a roster of applicants on the Moscow State University site, confirming the identity of his father.

Geotagged photograph from “ddanexx”‘s Instagram profile for Moscow State University, and a comment that he is in the social sciences department.

Applicant list from the Moscow State University’s site, listing Daniil Aleksandrovich Galushka (son of Aleksandr Galushka) as a student in the social sciences department.

Thus, with all of this information combined, Diana and Anna were able to confirm that the “Rich Kid of Russia” with the expensive car (among other assets, elsewhere in his Instagram account) is the son of a high-ranking Russian minister. The official tax declarations of Aleksandr Galushka for 2015 list his income as about 6.6 million rubles (about $100,000), and ownership of a Toyota Alphard, RAV4, and the Chevrolet Camaro that his son shared photographs of on Instagram.

In this case, the father of “ddanexx” officially declared the Camaro as his (or, to be more precise, his wife’s) property, but the collection of vehicles, apartments, and other assets seen in this Instagram account, along with other members of the Galushka family (including over $40,000/year tuition at a foreign private school), seem to outweigh the minister’s salary. This research did not identify any secret, undeclared assets, but the discovery, research, and verification process can be replicated in other cases both in and outside of Russia to add evidence in corruption investigations.

More on the social media materials of friends and family of politicians uncovering corruption:

- The Guardian: Yachts, jets and stacks of cash: super-rich discover risks of Instagram snaps

- Novaya Gazeta/OCCRP: The Secret of St. Princess Olga

- Bellingcat: Yachtspotting: OSINT Methods in Navalny’s Corruption Investigation

- Bellingcat: A Ferrari for a 13-Year-Old Boy: OSINT Methods in a Ukrainian Corruption Investigation

Searching Databases

Much of this guide has described how to find leads in corruption cases, but that is only one part of the research process. Most corruption research is conducted with checking public and semi-public databases, such as tax declarations, offshore records, land deeds, and so on. The best collection can be found at the OCCRP’s Investigative Dashboard, which centralizes millions of files, including hundreds of business registries, land tribunals, court registries, and other databases for countries all over the world. The dashboard also includes news articles, Wikileaks State Department Cables, and other documents that can provide additional context to the individual or entity you are researching.

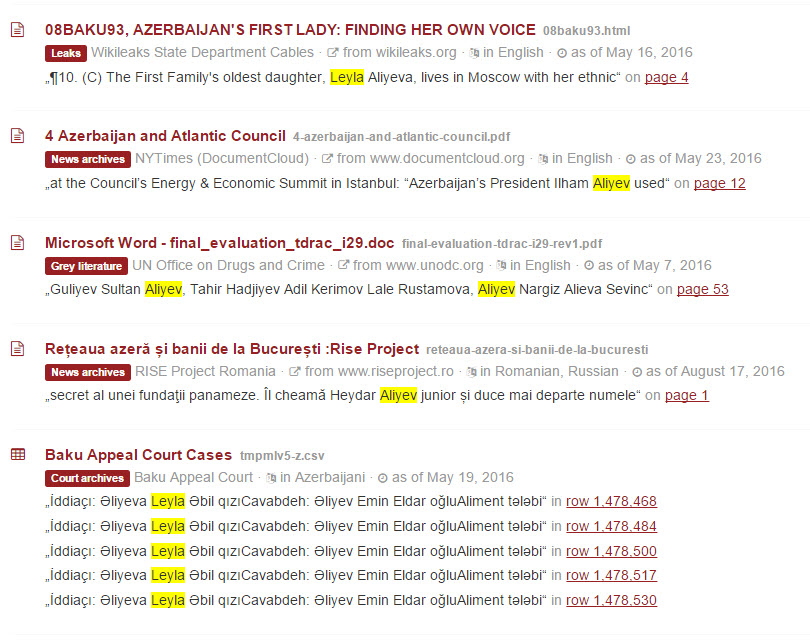

For example, searching for Leyla Aliyeva, the daughter of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, provides us with a plethora of information, including Wikileak cables, news articles, UN documents, and court archive documents from Baku.

These documents are all freely accessible and downloadable from the OCCRP’s website, including notations of exactly where in these files–which are sometimes quite large–you can find relevant information.

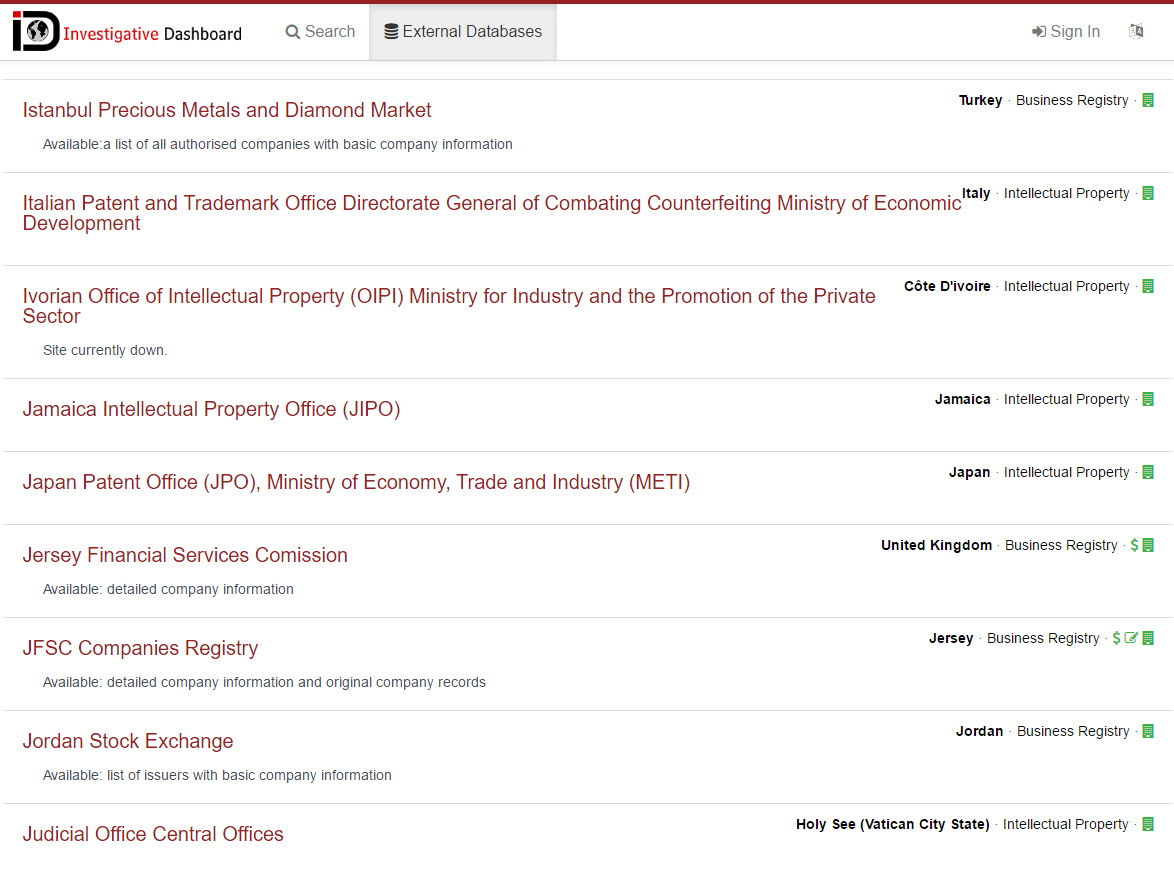

The OCCRP also has a comprehensive list of external databases, as not every database has been centralized onto the Investigative Dashboard. There is no one-size-fits-all guide for navigating these databases, as they differ in effectiveness, ease of use, language accessibility, and other factors.

Screenshot of the OCCRP’s Investigative Dashboard listing of external public databases.

Looking for Money Laundering

Investigating money laundering seems like a complex task that is better left to dedicated researchers at places like the FBI and OCCRP, and to a large extent, this is completely correct. To effectively unearth, investigate, and prosecute money laundering, one must have access to financial records, be able to follow paper trails through foreign banks, closely read loan contracts with shell companies, and other processes. However, it is still possible to conduct some open source research that complements a more exhaustive investigative process.

The process of laundering money often includes multiple corporate entities using numerous transactions, all under the guise of a legitimate business. As described in the 2012 text Fraud Examination, there are some indicators that raise suspicion, including businesses that:

- Are set up with no apparent commercial purpose

- Receive large amounts of money from overseas, which are matched by payments of similar size to other overseas countries.

- Purchase goods and services at prices significantly above or below market price.

- Pay or receive agents fees or commission that appear out of line with the norm within their business sector.

- Have a high turnover in relation to the size of their business.

- Have an unduly complex business structure that serves no apparent purpose.

As seen in the aforementioned OCCRP dashboard, most countries have their own standards for making information public that can help you determine if an organization (often shell companies) fit any of these criteria. For the United Kingdom, Companies House (now in beta) allows us to search through companies and the documents and individuals linked to them. A new requirement in the United Kingdom requires that all live companies in the country file the identities of their beneficial owners at Companies House–for more information on this new requirement, find a summary here and information on how the legislation came about here.

A company’s filing history will be available, along with who incorporated it, the shareholdings and shareholders in the company, and so on. Analyzing this open source information assists one in finding out who the beneficial owner of a company really is, which (theoretically) should be much easier with Companies House and the legislation requiring most companies to disclose key pieces of information. Additionally, the annual reports allow one to identify suspicious behavior, such as an significant loans and investments the company has made, dramatic increases in turnover, and if identical amounts are both owed to creditors and owed from debtors–indicating that the company is likely a thoroughfare through which money can flow.

Open source information alone will not allow you to conduct a full investigation into money laundering, but this type of research can give you leads to further investigation and follow through on further research.

Advice from the Experts

Iggy Ostanin is an investigative journalist at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and Bellingcat contributor. He is interested in open source investigations, anti-corruption research, and the use of disinformation in media.

Investigating corruption can be effective when trying to combine multiple pieces of evidence from different sources. A yacht can lead you to company records and shipping registries, and ownership or use can be verified using social media such as Instagram. Information from social media can then be verified using geolocation and trying to find other contextual information about the time and place. If someone traveled to the coast of Italy to get aboard a yacht, could they have been in town for an event? Similarly looking at the crew members or other people who work on the periphery of the asset you are looking, whether it’s a mansion or anything else can be facilitated by social media. This can be a good way of finding sources for interviews.

We asked for advice from journalist Yulia Makarenko and a producer from Ukrainian television news channel 112 Ukraine. Yulia and the producer work on the corruption-based television program “People’s Procurator” (“Народная прокуратура”).

Producer: Before we treat any subjects for investigation, we conduct basic research on social networks and in the mass media. We had an investigation where we showed the secret life of a lustrated Yanukovych-era prosecutor. In this program, we talked about how he gave a Ferrari as a birthday gift to his 13-year old son, and also showed all of his other cars (such as a Land Cruiser 200, BMW 740, Jaguar F-Type, Lexis RX 360), the luxurious life that his wife leads, their expensive trips, real estate, and plenty more that would be impossible to pay for with the salary of a Ukrainian prosecutor. We found all of this with open source information, and the social network page of his wife was particularly valuable. After finding this information, we checked and confirmed it all via government registers, using “data journalism,” and receiving answers to our requests to informational resources, plus going to the guy’s house.

Yulia: Of course, openness and sometimes the bragging of relatives can help us to expose government officials. And it’s not just the teenage relatives who brag. Many times we find the social networks pages government officials’ wives where they post photographs showing off gold Rolexes that cost as much as a one-bedroom apartment in the capital. Very often, they use long-forgotten social networks, such as “Odnoklassniki” [a Russian-language social network that has waned in popularity in recent years due to the emergence of Vkontakte, Facebook, and Instagram]. Perhaps they do this in hopes that no one will look there?

When looking for the property of government servants in their income statements, we often find empty sections [when officials leave categories such as “place of residence” blank, in order to publicly conceal their often lavish residences obtained by illicit means or funds]. In such cases, it is important to ask for information not only from the official register of real estate rights, but also to duplicate the request with the telephone directories that everyone with an internet connection can access. There were times when information was not accessible in the registry, but in the directory we would find a street name and number. At first it seemed like no one lives at the address we found, but upon arrival, neighbors confirmed otherwise.

Ruslan Leviev is the founder of the Conflict Intelligence Team and assisted in open source research with Alexey Navalny’s anti-corruption group FBK in 2012-13.

When investigation corruption with government officials, the imprudence of people close to them (family, friends, colleagues) in publishing information online helps us. As they do not have any skills with information security, they believe that the property shown in published photographs does not show any connection with the official they are close to, thus they often publish revealing information. I remember many examples of how the connection between an official and company that won a tender was established thanks to profiles on social networks–they were friends with one another. I remember how the children of officials published photographs of cars and dachas on their social network accounts. The researcher’s task: finding this information. Find the profiles of the official’s relatives. And then closely watch the profiles of the friends of these relatives. A multistage search with a little bit of improvisation will help you find information.