The Websites Sustaining Britain’s Far-Right Influencers

Editorial Note: As usual, all the information in this investigation comes from open sources. However, Bellingcat has decided not to link to content or profiles of people promoting hatred or disinformation, and only named those who could already be considered prominent public figures. Given the many possible pitfalls of covering far-right communities, we tried to ground our reporting and writing of this story on the principles laid out in Data & Society’s report “The Oxygenation of Amplification”.

Another white supremacist YouTube video draws to a close. In this 21-minute monologue, a Brit—with 131,000 subscribers and 9.2m total views—advocates for a white ethnostate based on a racist caricature of black inferiority. In others, he stereotypes migrants as rapists and orders his followers to “fight or die”.

YouTube suspended, then reinstated, his main channel in 2019. He has since had 2.5m more views. His accounts aren’t monetised, so he isn’t paid for clicks. Instead, he uses YouTube—and Twitter—to direct people to other platforms where he can profit from his white supremacist conspiracy theories.

In video descriptions, he links to fundraising pages on SubscribeStar, PayPal, and Teespring; keys for cryptocurrency donations; and accounts on Telegram, Minds, BitChute and Gab—social media platforms popular among the far-right.

“Your support makes my work possible!” he writes.

A Bellingcat investigation into the online ecosystem sustaining popular figures on Britain’s far-right has found that many are using YouTube and other mainstream platforms—even from restricted accounts—to funnel viewers to smaller, lower-moderation platforms and fundraising sites, which continue to pay out.

This investigation was based on a database Bellingcat compiled—over three months—of popular personalities on the British far-right. It comes as the British government prepares key legislation to compel tech companies to make the internet a safer space.

Members of the English Defence League demonstrate in Walsall, Birmingham, central England, August 15, 2015. Photo (c): Reuters/Andrew Yates

Like other prominent international far-right influencers, Brits promoting hate and conspiracy theories are capitalising on the global reach of the biggest platforms to gain followers and money elsewhere. This despite a recent wave of deplatforming, and the fact that much of their content violates the rules of the websites involved: from YouTube, Facebook and Twitter to fundraisers PayPal, SubscribeStar, Patreon and Ko-fi.

Some sites down this funnel have been co-opted by far-right communities. Other “alt-tech” alternatives actively endorse them. Many of these platforms, modelling themselves as free-speech advocates, were used to agitate for—and stream—the storming of the US Capitol in January.

Online Harms

Tech platforms’ amplification of harmful ideologies with real-world consequences is undeniable, yet they have consistently proven themselves unable—or unwilling—to consistently enforce their own terms of use.

Several deplatformed Donald Trump after the US Capitol break-in, which also led Google, Apple and Amazon to stop serving Parler, an alt-tech Twitter substitute (though it is now back online).

But such acts remain the exception, so governments are turning to stricter regulation.

This year, the UK will bring its Online Harms Bill before parliament, legislation empowering an independent regulator to fine platforms that don’t restrict unsafe online content. Civil society has urged for smaller platforms to be included.

The EU is currently weighing up a Digital Services Act, which would allow regulators to make larger platforms responsible for protecting users, with fines if necessary.

In the US, hate speech is protected under the First Amendment unless it incites crime or threatens violence.

Online Influence

The British far-right has helped shift narratives about Islam and migration rightwards in recent years, contributing to the 2016 murder of MP Jo Cox by a far-right terrorist.

Nevertheless, it is increasingly splintered and organisationally weak.

The deplatforming of far-right groups like Britain First and figures like Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (better known by his pseudonym Tommy Robinson) has severely restricted their influence.

But online spaces, especially under lockdown, offer easy access to far-right politics.

The British far-right has moved away from electoral politics in recent years, becoming “post-organisational”, according to Joe Mulhall, Senior Researcher at anti-racism organisation Hope Not Hate (HNH). Mulhall has noted the rise of what he calls “networked influencers”. “It’s almost like a school of fish, they move together, independently, towards a particular issue,” he told Bellingcat, and “the people who rise to the top… essentially direct the school.”

Far-right Brits get less press than their US counterparts, but sites like YouTube and Twitter mean they can still reach worldwide audiences and contribute to conspiracy theories—like the Great Replacement theory—that have influenced far-right attacks. Far-right figures on both sides of the Atlantic also use the same platforms, sharing ideologies on each other’s shows.

This is especially important given that last November, British police stated that far-right extremism, fuelled by online radicalisation, was the UK’s fastest-growing terror threat.

The Far-Right Funnel

The “radicalisation pipeline”, whereby recommendation algorithms on YouTube and Facebook push viewers towards increasingly-extreme content, is well-documented. But far-right actors are also funneling viewers off of mainstream social media to low-moderation platforms and fundraising sites, seemingly motivated by a desire to reach as many people as possible and the fear of being deplatformed. “I am one of the last survivors on here,” one British fascist recently said of YouTube. “We are nearing the end.”

Meanwhile, talking to the camera with a Union Jack hanging in the background, Carl Benjamin, an anti-feminist YouTuber with nearly 800,000 subscribers across two active channels, urged viewers to “follow on the alternate social media platforms” in a recent video, “because things are going to get quite messy.” (In a lengthy written response to our request for comment, Benjamin rejected the label “far-right” and criticised deplatforming.)

Drawing partly on recent HNH reports and our own research, we compiled a database of prominent British far-right influencers, archiving content—including hatred based on race, religion, gender and sexuality—that broke community standards.

All but two of the 29 figures used—one or a combination of—YouTube, Twitter or Facebook to promote fundraising sites and smaller platforms, putting links in posts, bios and video descriptions, and pleading for support.

Our methodology could easily be replicated for researching far-right communities elsewhere, especially given that many of the platforms and behaviours are the same. This funneling practice, for example, appears common in the US. Alt-right figure Nick Fuentes uses Twitter to direct followers to his website, which links to his Telegram account and sells merchandise.

“Cosy New Homes”

Mulhall of HNH splits the platforms into three groups: “mainstream” ones like YouTube, Twitter and Facebook, “which have a far-right problem, but are ostensibly not far-right platforms”; “co-opted platforms”, like DLive and Telegram, which the far-right have migrated to “en masse” because of low moderation; and “bespoke platforms” created by people with far-right leanings, such as BitChute, Gab and Parler.

“The different platforms serve different purposes,” Mulhall added.

The far-right use mainstream platforms to recruit and push propaganda, while bespoke platforms are “havens where they can do [and say] what they please.”

Where possible, these platforms are used simultaneously, highlighting why researcher Jessie Daniels calls white nationalists “innovation opportunists”, who find openings in the latest technologies to spread their message.

YouTube was by far the most popular mainstream platform among those we analysed: 24 of the 29 had an account. Twitter (16 of 29) and Facebook (11 of 29) were also popular.

But recent clampdowns—and the prospect of further action—have made some far-right figures feel more reliant on smaller sites.

Many called for followers to use Gab and Telegram after Parler was shut down, for example. Several of the Telegram accounts we tracked subsequently saw steep increases in followers.

Telegram

A British white nationalist, who co-runs a small but growing fascist group, recently described two apps as his “cosy new homes”: one was messaging app Telegram.

Telegram was the most popular of the non-Big Tech platforms among British far-right influencers: 23 of the 29 had accounts. Its rules governing content are minimal, and while it has no stated political affiliations, unlike the alt-tech platforms, it has traditionally put up little resistance to far-right extremism.

Under pressure from activists, this January Telegram removed “dozens” of Neo-Nazi channels calling for violence.

This was “welcome” said Mulhall of HNH, adding, however, that Telegram had “failed to act continuously” for years.

We found public posts denying the Holocaust and demonising migrants as rapists and murderers. Telegram did not reply to a request for comment, and the posts remain online.

BitChute

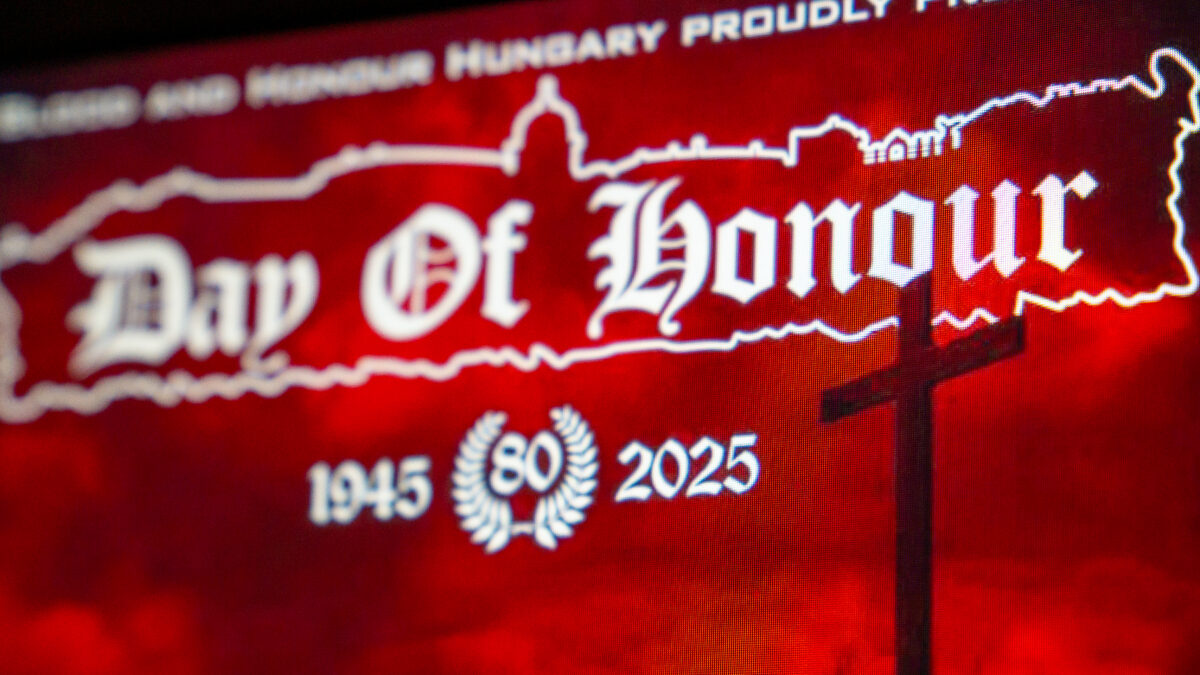

Next was BitChute, a growing British video-hosting site used by 20 of the 29 on our database that is rife with racism and hate speech. For example, one Brit published a video falsely arguing that diversity was a deliberate attempt to ethnically cleanse white people.

BitChute allows influencers to monetise such content, linking through to fundraising websites such as SubscribeStar, various cryptocurrencies, Paypal and others.

BitChute’s founder Ray Vahey actively promotes conspiracy theories involving anti-semitism, COVID-19 and QAnon through the platform’s Twitter account.

In 2019, PayPal and crowdfunding website IndieGogo banned BitChute from using their services, while Twitter now warns people clicking on BitChute links. However, BitChute still integrates PayPal links for creators raising money.

In January, for example, the Community Security Trust, a UK-based organisation that works to protect Jewish communities from anti-semitism, reported BitChute to Ofcom, the regulating body of the Online Harms Bill.

In the same month, BitChute added a new clause prohibiting hatred inciting direct violence.

But racist slurs, Nazi imagery and calls for violence against Jews remained common in video comment sections.

In an emailed response to our questions, BitChute rejected our characterisation of the site and claimed that it was working to improve its moderation capabilities, as it did in response to similar criticisms made in July 2020.

Gab

The other “cosy new home” was Gab.

The alt-tech social network, which has reportedly spread anti-semitic hate online, was used by 18 of the 29 we studied, some of whose accounts saw a large boost after the fall of Parler. Posts on Gab contained hate and conspiracy theories—including anti-semitism and racist remarks about the origins of a US Congresswoman—but according to its terms of service Gab doesn’t punish users “for exercising their God-given right to speak freely”.

In February, Gab declared on its now deleted Twitter account that it would only respond to inquiries from “Christian media compan[ies]” and directed “pagan propagandists” to check its blog for press statements.

Several other platforms popular with the US far-right, including Rumble and Minds, seem less widespread in the UK.

DLive

Ten of the 29 used DLive, a live video-streaming service—using blockchain technology—originally designed for video gamers.

DLive banned multiple white nationalist, anti-semitic US influencers for livestreaming the Capitol attack, declaring there was “no place” on the platform for “hate speech”, including “white supremacism”. But in November the Southern Poverty Law Center, an American nonprofit, detailed how white nationalists were making tens of thousands of dollars spreading hate on DLive. A whistleblower told Time magazine in August that their concerns about hate on the platform were ignored by its co-founder, Charles Wayn, because the streamers were helping DLive grow.

Far-right Brits, fearful of restrictions, rarely leave their streams online for long.

DLive did not reply to a request for comment.

Funding The Far-Right

As well as examining the platforms giving these figures exposure, we used our database to track which fundraisers were helping far-right Brits earn money and, when donations were public, how much they were making.

At the end of a YouTube video with nearly 1m views fueling racist caricatures of Muslim refugees as rapists, Paul Joseph Watson, known for his work with conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, implores viewers to send him money via SubscribeStar, a low-moderation fundraising platform favoured by the far-right.

He links to his page in the video description, along with cryptocurrency keys, merchandise and alt-tech accounts. His main YouTube channel—which is still monetised despite the Islamophobia, racism and COVID-19 conspiracy theories—has 1.87m subscribers. His Twitter account has 1.1m.

At the time of writing, Watson was earning $7365 (£5224) per month from SubscribeStar alone—a figure which is likely to be higher, assuming that some of his 1473 supporters pay more than the minimum subscription (which ranges from $5-$250). Watson did not reply to an emailed request for comment.

SubscribeStar is just one of the fundraising websites and intermediaries providing revenue for—and profiting from—British far-right influencers.

Funding sources include paid chats on video streams, monthly subscription and one-off donation sites, selling products online, website donations and cryptocurrencies.

Megan Squire, a professor of Computer Science at Elon University in the USA who studies online extremism, breaks these revenue flows into two broad categories. The “old school” options, like merchandise and monthly dues; then what she calls “monetised propaganda”, such as donations on websites or during live-streams.

The option with the most cash potential, Squire told Bellingcat, is “live-streaming for entertainment”.

Video Streaming

While streaming live on YouTube or DLive, far-right influencers are paid to engage with viewers and read out their comments or questions via “SuperChats”.

YouTube sometimes removes SuperChat functions for accounts that violate its terms of service, while DLive demonetised all political streams following the storming of the US Capitol, which means there’s less money to be made on the site. But there are still loopholes.

British white nationalist Mark Collett, for example, temporarily turns off the label marking his DLive streams as “Political” (Other labels include “Music”, “Chatting” and “Retro Games”). He also posts them to BitChute, and simultaneously streams some of the less problematic ones to YouTube.

Collett also does gaming streams on DLive, which have no monetisation restrictions. Every stream begins with how viewers can follow him and support his work.

Entropy, a tool used by five of the 29 that wraps around streams on other sites, allows demonetised streamers to keep taking donations for uncensored hate—unless the streamer decides to mute or ban “anti-whites” as has been known to happen.

Entropy—whose founders did not reply to an email requesting comment—recently removed references to being a streaming solution “in an Era of Mass Censorship” from its website. But the founders have actively recruited far-right figures, like Collett, who has described them as “very friendly towards us”.

Entropy allows Collett to sidestep his YouTube and DLive restrictions. BitChute allows him to take BitCoin donations and post white nationalist content unlikely to be taken down. YouTube, where he now posts more gaming than political videos due to censorship fears, is mainly a recruiting tool, used to funnel new followers to unfiltered white nationalist views on Telegram, BitChute, and Gab.

On a recent YouTube stream of the game Call of Duty: Warzone, for example, Collett invited gamers to join a “nationalist Warzone Telegram group”.

Beneath the video description, which included Collett’s Entropy and Bitcoin details, one commenter wrote: “I’m not a nationalist but I don’t like the government can I join 😁”

Collett replied: “Jump in lad!”

In an emailed response to Bellingcat, Collett defended his recruitment strategies and claimed that this investigation was an example of the media colluding with Big Tech to bring down his movement.

Subscription Platforms

One of the most popular money makers—used by 10 of the 29—was SubscribeStar, a Russian-owned, US-incorporated site with a history of attracting far-right figures deplatformed from other fundraisers. A testimonial on the homepage from a Swedish white nationalist YouTuber refers to SubscribeStar as a “safe haven” in “a time of censorship”. BitChute has its own page on the site and raises at least $28,210 (£20,010) per month.

SubscribeStar drew attention in 2018, when YouTuber Carl Benjamin migrated there after being banned from Patreon for using “racial and homophobic slurs”. PayPal subsequently refused to operate as SubscribeStar’s payment processor.

When Patreon, used by four of the 29, removed a white nationalist, anti-semitic YouTuber in March 2020—cutting, he claimed, 90% of his channel’s income—he directed his combined 176,000 followers to accounts on SubscribeStar and PayPal, and later to buy his merchandise. He doesn’t declare how much he makes on SubscribeStar, but others are more open. One influencer with more than 100k followers who promotes white nationalism earns $1,582 (£1,121) monthly, on top of other funding streams.

Though SubscribeStar did prevent prominent US alt-right figure Richard Spencer from joining in 2019 and claims to prohibit “hatred toward any social or ethnic group”, it appears largely untroubled by hosting white nationalists.

Neither Patreon nor SubscribeStar replied to our requests for comment.

Other fundraisers, including PayPal and Ko-fi, also enable British far-right figures to make money.

Ten of the 29 figures had PayPal accounts, despite prohibiting users from providing “false, inaccurate or misleading information” and promoting “hate, violence, racial or other forms of intolerance”. It doesn’t display donations publicly. PayPal did not respond to an email requesting a comment on these findings.

Ko-fi, used by four of the 29, does display donations. One far-right influencer, who espouses anti-semitic and Islamophobic conspiracy theories, earned a minimum of £2,052 ($2,894) on Ko-fi over the past two years, on top of his regular Patreon and SubscribeStar income; the latter of which is $840 (£595) monthly.

Another of the 29, who has also spread anti-semitic conspiracy theories and argued for bombing refugee boats, has earned a minimum of $2,534 (£1,843) on Ko-fi and a similar site, Buy Me A Coffee, over an undisclosed time period, on top of his private income from SubscribeStar, website subscriptions, Teespring, CashApp, and cryptocurrency donations.

Buy Me A Coffee, which was used by two of the 29 figures, did not respond to an email requesting comment. Neither did Ko-fi nor CashApp, although the latter did delete both the accounts we flagged in our email.

These amounts vary. Some figures with smaller followings only earn a few hundred dollars on sites with publicly-listed donations. But these amounts are likely far below real earnings: a large majority use multiple, private funding streams.

Ultimately, these websites are enabling the far-right to earn money for trafficking in hate.

SubscribeStar takes a 5% cut of all transactions, while forbidding all forms of “hatred” and “defamation” based on identity. Ko-fi does not take a cut, but charges $6 per month for Gold accounts, used by four of those we followed. It prohibits using Ko-fi in connection with “hate speech, intimidation or abuse of any kind”. PayPal takes no fee on personal donations (if there’s no exchange rate), but does charge for payment processing on other sites, which it does for Ko-fi, Buy Me A Coffee and Patreon. Patreon takes 5-12%, condemning “projects funding hate speech, such as calling for violence, exclusion, or segregation”. Buy Me A Coffee takes 5% and advises users against “anything threatening, abusive, harassing, defamatory” etc. on the site.

Websites

Another funding route, particularly for political groups, is official websites. Amazon’s Cloudfront, which recently dropped Parler, hosts the sites of Britain First and fascist group Patriotic Alternative. The latter, along with Yaxley-Lennon’s site, For Britain, and three others, have donations processed—for a fee—by Stripe, a payment processor that withdrew its services from Donald Trump’s fundraising website this January and from Gab in 2018 after the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting. The perpetrator had consumed and posted anti-semitic conspiracy theories on the site.

WordPress hosts the websites of five of the 29, including Yaxley-Lennon and enables them to monetise their online presence.

After a public spat with a major tea brand over its support of Black Lives Matter, one Brit developed her own tea company, also on WordPress. She recently pledged to invest the profits “back into activism and community-building.”

Amazon Web Services, Stripe and WordPress all failed to reply to requests for comment.

Like with Amazon abandoning Parler, many of these sites depend on major internet infrastructure companies.

Marketing industry advocate Nandini Jammi, one of the former leaders behind the anti-hate campaign Sleeping Giants, told Bellingcat that with these platforms, “the fight will go all the way up to Mastercard, Visa, American Express.”

Merchandise

Book sales on Audible and Amazon provide funds for six of the 29. One book listed on Amazon—and endorsed by former KKK leader David Duke—avocates Nazi ideology, misogyny and homophobia. Under the listing, Amazon recommended books by associated white nationalists, British fascist ideologues, anti-vaxxers and the Unabomber terrorist’s manifesto. Amazon has been repeatedly criticised for selling items promoting hate. Its book policy prohibits “content that we determine is hate speech… or other material we deem inappropriate or offensive”. One Brit claimed that his Islamophobic book was removed in August 2020, although his other books are still on sale.

The head of Britain First, Paul Golding, who has been convicted of racial and religious harassment, proudly features on the cover of his own book on the site. Amazon also sells an audiobook, narrated by a leader of a far-right group, that recites a debunked anti-semitic white nationalist conspiracy—The Kalergi Plan—that feeds into the Great Replacement. At the time of publication, this audiobook is currently listed at #35 on the Audible European Politics bestsellers list.

Seven of the 29 used Teespring, an e-commerce platform where customers design and sell merchandise. Some far-right Brits use it to sell clothes, for example, or mugs displaying their faces or logos, others use discrimination wrapped in jokes. One design, for example, plays on COVID-19 social distancing guidelines to advocate for ethnic segregation.

Repeated public criticism for failing to apply its own moderation policies has pushed Teespring to remove clothing showing swastikas, for example, and jokes about killing journalists. The site also sold the “Camp Auschwitz” hoodie that appeared during the Capitol break-in. The site takes an unspecified cut of each sale.

Teespring (now just Spring) deleted all seven accounts we flagged, saying: “we categorically do not allow or condone any content which promotes hate” or groups promoting such content.

Finally, eight of the 29 took various cryptocurrency donations, which don’t register public amounts.

Reluctance to Moderate

Efforts to control the spread of hate on YouTube, Twitter and Facebook have traditionally been limited by profit incentives, fears of “playing politics”, and an ideology influenced by Silicon Valley tech-libertarianism and US constitutional ideals.

Squire of Elon University criticised the ongoing adulation of this outdated “move fast and break things” tech ethos.

Platforms have been caught out numerous times for hosting hateful content in recent years. Despite the haphazard attempts at more hands-on moderation and the scrutiny of recent weeks, we found videos and posts appearing to violate community standards on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, DLive, SubscribeStar, PayPal, Ko-fi, and Patreon.

Deplatforming those responsible is not a “silver bullet” said Mulhall of HNH, but “getting rid of some of the explicitly bad actors” helps cultivate a “pluralistic online space that will actually expand free speech.”

Plus, he added, “getting them off the major platforms prohibits a whole array of negative effects: the ability to recruit, push propaganda, and raise money. So the lifeblood of movements is cut off.”

Unsafe Spaces

In response to tighter moderation, some are now pushing for the far-right to create new infrastructure to sidestep reliance on Big Tech, including switching to video hosters using blockchain, which are decentralised and therefore not reliant on companies susceptible to public pressure.

“Each of these waves [of deplatforming] have created a sense within the far-right that they need to create alternative spaces,” said Mulhall.

For now, many remain on mainstream platforms.

YouTube regularly posts about its technological advances in moderation, but only explicitly began prohibiting the promotion of Nazi ideology, Holocaust denial and “videos alleging that a group is superior in order to justify discrimination, segregation or exclusion based on” identity in June 2019. It then took until October 2020 to prohibit “content that targets an individual or group with conspiracy theories that have been used to justify real-world violence”.

This lethargy has consequences. The Australian terrorist who killed 51 people at two New Zealand mosques in 2019, for example, was a keen follower of far-right YouTubers and online conspiratorial content, according to the New Zealand Royal Commission. Two leaders of a fascist group that we studied told YouTube viewers the names and Black and Jewish ethnicities of two British Electoral Commission officials who rejected their application to become a political party.

A YouTube spokesperson told us, “we removed several videos from the channels mentioned in [this] report for violating our policies,” adding that the platform had a “transparent” approach to removals: if a channel gets three strikes in 90 days it will be permanently closed. They did not reply to a follow-up request asking which of the accounts had new restrictions or strikes placed on them and which videos were removed. YouTube deleted four accounts belonging to two of the far-right influencers we identified, but did not acknowledge doing so in their emails. It chose to leave the video containing personal information about the Electoral Commission employees online.

On Twitter, we found tweets calling migrants “parasites”, for example, and others containing anti-semitism and Islamophobia, despite the platform’s stated commitments to combating hate speech. Twitter was repeatedly cited as an important recruiting ground. As one white nationalist Brit put it, they got “a better response from newbies” there.

Twitter claims to have clear Abusive Behaviour and Hateful Conduct policies and to take enforcement action once violations have been identified. We flagged 16 active accounts. Eight of these subsequently disappeared. Twitter then claimed that the accounts had been suspended prior to their team receiving our list.

The platform also deleted select tweets from other users we flagged, but stopped short of deleting their accounts.

Facebook, a website that claims to “not allow hate speech”, hosted videos blaming ethnic minorities for crime and spreading COVID-19 disinformation. A company spokesperson told us: “we do not tolerate hate speech on our platforms and we are investigating the information shared,” and provided some statistics evidencing their moderation successes.

At the time of writing, Facebook has taken no action on the links we sent them.

“If [platforms] can make plenty of money, they can get enough moderators,” said Mulhall of HNH. “You’re creating unsafe online spaces.”

But even when they do moderate, there are ways around restrictions. Far-right commentators often promote one another’s work, which is especially useful if the person being promoted on, for example, Twitter, has been banned. On YouTube, deplatformed people make appearances on others’ channels, where they can plug their own accounts elsewhere. Some figures who have been banned simply open new accounts (Twitter deleted three such accounts when we flagged them). Others implore followers to share their links on platforms that have banned them.

“They’re always going to want to get back into the mainstream,” said Mulhall. “That’s where the fun is, that’s where the people are, and that’s where the money is.”

We told 19 websites mentioned in this piece about the content published, promoted, or fundraised for on their services. Fourteen have not replied to our requests for comment. Four took some kind of action.

For now, these websites remain vital for many on the far-right, especially with COVID-19 keeping potential sympathisers off the streets and behind their keyboards.

“It’s an economy of hate running on the same platforms and services that we use to build legitimate businesses that contribute to society,” said Jammi. “They effectively are the reason that extremism has been able to survive.”