Navalny Poison Squad Implicated in Murders of Three Russian Activists

- In our previous investigation, we disclosed the existence of a clandestine unit within the FSB’s Criminalistics Institute, members of which had shadowed opposition leader Alexey Navalny for nearly five years. Members of the unit with medical and chemical-weapons background, travelling in groups of two or three, had followed Navalny on more than 30 flights during his 2017 presidential election campaign. Three members of this squad had been near him during a suspected poisoning of his wife in July 2020, and during his near-fatal poisoning in August 2020.

- We also disclosed that this unit was supervised by Col. Stanislav Makshakov, deputy director of the Criminalistics Institute and a scientist involved with Russia’s military chemical weapons program, which according to public sources had developed over 20 highly toxic materials including organophosphates of the Novichok type. Before Navalny’s poisoning with Novichok, Col. Makshakov was in frequent communication with scientists from the Signal Institute, which a previous joint investigation linked to Russia’s surreptitiously renewed chemical weapons program.

- A follow-up report presented additional validation of the role of the FSB’s Criminalistic Institute in the poisoning of Alexey Navalny obtained through an inadvertent admission by one of the unit’s chemical weapons specialists – Konstantin Kudryavtsev – who had been dispatched to Omsk following the poisoning to dispose of any traces of the toxic substance on Alexey Navalny’s personal items.

Our initial report disclosed that the FSB poison squad traveled in clusters of two or three people to many more destinations that can be explained with their now-known efforts to murder Alexey Navalny. We continued exploring this unit’s extensive travel data (see this article on our methodology, as previously seen with our Navalny investigation) seeking to link their itineraries to previously unexplained deaths of political activists, as well as poisonings of prominent figures. To this end, we crowdsourced the research by making public the itineraries of 10 of the known members of the FSB squad.

We received more than 500 contributions from volunteers, journalists and other media, some of which pointed to previously unknown coincidences between squad members’ presence and unexplained deaths. We analysed all input and applied strict criteria in selecting potential leads for further investigations. For example, overlapping trips had to number no fewer than two with the presence of at least two squad members during each trip; or that a group of no less than three squad members needed to be present at a location where a suspicious unexplained death or severe poisoning of a public figure had taken place. These criteria were selected based on probabilistic assessment of the risk of false positives.

On the basis of these criteria, and further investigation, we were able to match the movements of the FSB’s poison squad with the suspicious deaths of three public figures between 2014 and 2019.

Two of the cases, which are presented below, conform to our self-imposed criteria, while another case does not have sufficient data points to fit the criteria but bears other striking similarities to one of these two cases.

Based on the sheer volume of the squad’s travel data, this list is likely not exhaustive, and our investigation into other potential missions will continue. Furthermore, this list of victims uses travel data as a point of departure, and is therefore limited only to operations that took place outside of Moscow.

The Journalist From Nalchik: Timur Kuashev

At about 6:30 pm on 31 July 2014, Timur Kuashev, a 26-year-old citizen journalist from Nalchik, the capital of Russia’s small North Caucasus republic of Kabardino-Balkaria, walked out of his home. He lived with his mother who was an actress at the local theater; she had a premiere at 7 pm that evening and he had requested two tickets. After he offered the second ticket to a friend who said she was busy that evening, Kuashev took a shower, put on dress trousers and a shirt, and walked the short way towards the Rodina theater. A witness later said they saw him talk to some people in plain-clothes at a bus stop who came out of a car.

Timur Kuashev’s lifeless body was found the next day on a road into a forest in the nearby suburb of Khasanya, more than 15 kilometres away from his home. He was lying face-down in the dirt, and his body and face had bruises and hematomas. The official coroner’s report said he died of heart failure triggered by an acute viral infection. The report said the forensic analysis “did not discover exterior symptoms of violence or signs of self-defense”.

However, this is clearly contradicted by a photograph of Kuashev’s face taken by a friend just before his funeral, and now shared with us. The photo shows clearly visible symmetrical bruises on his upper cheeks, possibly from fingers clutching his head from behind, and a hematoma on his left eyelid. Crucially, a follow-up coroner’s report identified traces of an injection in Kuashev’s left armpit area that had been applied six to 10 hours before the body was found.

Thanks to lobbying by his father – a retired senior criminal investigator – a murder investigation was opened into Kuashev’s death. Following a local laboratory analysis of blood samples that found no traces of narcotics or known toxins, the initial investigation hypothesis was that Kuashev had been poisoned with an unknown substance. Samples were sent for additional forensic analysis to Moscow, but no trace of poison was found. The final prosecution report from September 2016 closing the criminal investigation found no clear link between the injection and Kuashev’s death, and chalked it off to coronary failure.

Timur Kuashev’s family did not consider the official investigation to be conclusive or valid. In comments to the news site Caucasian Knot, Khambi Kuashev pointed to the lack of any investigation into his son’s phone records from the date of his disappearance (there were two text messages from a service phone number that the investigators refused to pursue, due to – as the prosecution’s decision read – “risks of disturbance to the mobile operator’s systems”), as well as into the threats his son had reported in the months before. He also pointed to Timur Kuashev’s lack of any previously diagnosed medical issues. Additionally, the father, who spoke to our investigative team, says he had pointed to the fact that a USB drive was missing from his son’s computer, and that the keys to the apartment had not been on him when he was found – suggesting that someone might have entered his house after his disappearance.

Indeed, Timur Kuashev had alerted his friends – and even the authorities – of a string of anonymous threats he had received online as a result of his work as a journalist. As a blogger on LiveJournal – a popular blogging platform in Russia that had launched the careers of many researchers and journalists, including Alexey Navalny – Kuashev had relentlessly covered local politics in Kabardino-Balkaria, appearing to have irritated both local law enforcement and the FSB. Living in an autonomous republic which at times saw a spillover of violence from Chechnya, he had written articles on torture and persecution by security services for the popular regional news sites Caucasian Knot, Kavpolit and the magazine Dosh. He had also organized rallies against torture by police and was collaborating with national and local human rights organizations, and was an active member of the Russian opposition party Yabloko. According to his friends, relayed both in public statements and to our investigative team, Kuashev had been repeatedly summoned by both police and the FSB for questioning in connection with his work. Kuashev, an ethnic Circassian, had also been detained earlier that year at a rally marking the 150th anniversary of the last battle of the Caucasus War (a war that resulted in the incorporation of much of the North Caucasus into the Russian Empire and the forceful expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Circassians from their homeland). Two special agents from the police’s anti-extremism department had cautioned him about an article he had just written – which in turn caused Kuashev to file a complaint against the officers over their infringement of his right to free speech.

Kuashev also relentlessly covered a high-profile criminal case against 58 locals accused of involvement in the 2005 raid on Nalchik that was coordinated by Chechen rebel commanders, but which Russian security services claimed was instigated by foreign Islamist terrorist groups. The case was monitored by the Memorial human rights organization which criticized the extraction of dubious confessions via torture that were contradicted by other witness testimonies. The Russian journalist and political activist Maxim Shevchenko, editor of Kavpolit, told Bellingcat that Kuashev was the only local journalist who covered the court proceedings and repeatedly published damning critiques of the inconsistencies in the prosecution’s case. Shevchenko is convinced that Kuashev was murdered as a result of his interference with the Kremlin’s efforts to stage a smooth show trial. This theory is supported by other journalists such as Nadezhda Kevorkova, who, together with Shevchenko, conducted a journalistic investigation into Kuashev’s death and concluded that he was murdered.

Timur Kuashev had also been openly critical of Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine, including the 2014 annexation of Crimea. He had been outspoken in his criticism of the Kremlin and of Russian president Vladimir Putin, stating that the country needed a “a new revolution for change of government”. Just a few hours before he was killed, he posted a comment on Facebook in which he wrote that Putin’s enemies were dying “as if on schedule”.

Another source who cooperated with Kuashev and who requested not to be named due to safety concerns believed that during one of his many interrogations by the FSB, Kuashev had been coerced into cooperating with the security agency, but later reneged on the agreement. The source believes this to be the most likely reason for placing Timur Kuashev on the FSB’s blacklist, but we have been unable to confirm if this is true.

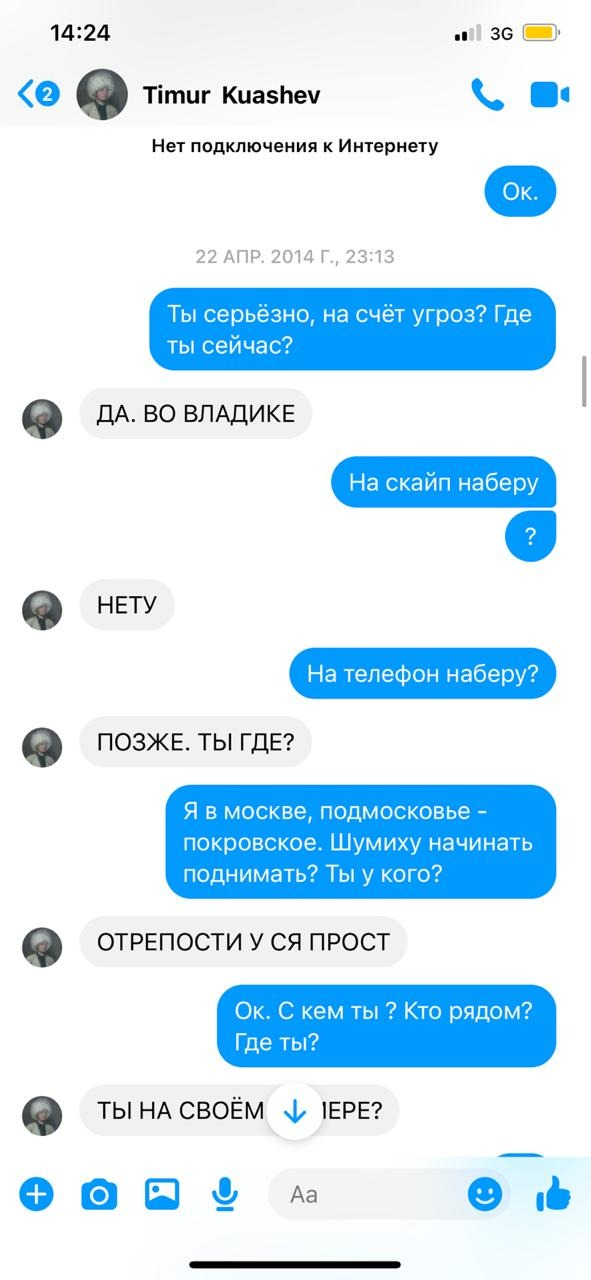

Facebook messenger exchange between Kuashev and a human rights activist from the North Caucasus republic of Dagestan from April 2014 in which Kuashev confirms he received threats. Screenshot provided to Bellingcat by the activist.

It is not clear precisely which of Timur Kuashev’s journalistic or activist endeavors may have contributed to him becoming a target of assassination. However, an analysis of travel data of FSB operatives from the poison squad of the Criminalistics Institute, as well as confidential documents from official prosecutorial investigation provided by an insider source, strongly suggests that his death was the result of a targeted poisoning operation by the same core FSB team that poisoned Alexey Navalny in 2020.

Reconstruction of the FSB operation

Based on partial airline data for 2014, we can see that the same FSB squad previously identified by Bellingcat in the context of the Navalny poisoning investigation were conducting an ongoing operation in the Nalchik area at least as early as 13 July 2014. On that date Konstantin Kudryavtsev, one of the unit’s chemical weapons specialists, traveled to Nalchik. There is no data about his return date.

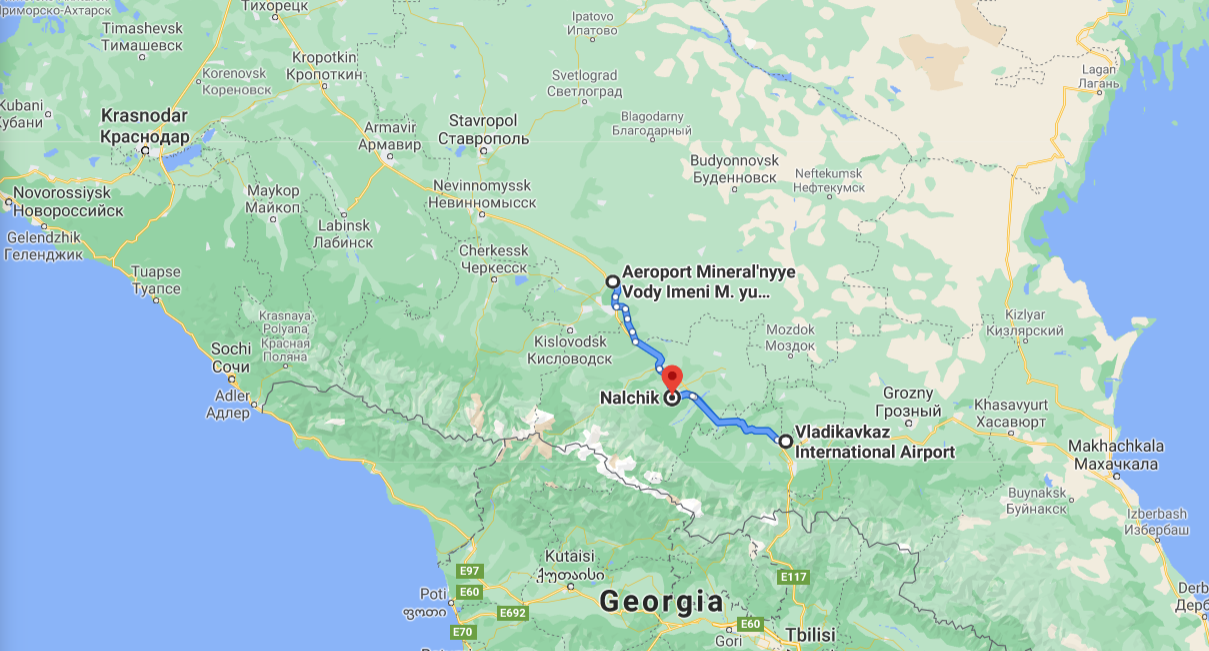

Nine days later, on 22 July 2014, Ivan Osipov – a decorated FSB officer and one of the senior members of the FSB squad implicated in the poisoning of Alexey Navalny – flew from Moscow to Mineralnye Vody, north-west of Nalchik. He had originally bought a return ticket for 30 July, but on that day he changed it for the following morning, 31 July. However he didn’t take that flight either, and changed it one more time – to a flight on 1 August 2014 at 2:05 pm. That flight back to Moscow departed several hours after Timur Kuashev’s body was found outside Nalchik, an hour and a half’s drive away.

Ivan Osipov’s decorated status

In Moscow’s citizen database, Osipov’s name is listed as a a person entitled to special benefits status. This marking is typically reserved for people with a high military distinction

Osipov was not alone in or near Nalchik on the eve of and at the time of Kuashev’s death. In addition to Kudryavtsev, at least three other FSB operatives had arrived in the region in the days prior. A critical second presence was that of Dr. Alexey Alexandrov, the other member of the FSB poison squad whose phone records placed him near Alexey Navalny’s hotel in the hours before he fell into a coma in Tomsk.

Unlike his colleague Osipov, Alexandrov flew to another nearby airport, Vladikavkaz, situated 100 km to the south-east of Nalchik. As disclosed in the inadvertent telephone admission by Konstantin Kudryavtsev, operatives of the FSB squad – even members of the same “brigade” – often travel on different flights to and from different airports to avoid detection. This modus operandi is corroborated by hundreds of flights of the FSB squad reviewed by Bellingcat. Alexandrov arrived one week after Osipov, on 29 July. Like Osipov, he initially had a return booking for 31 July but did not use it. Instead he bought a last-minute ticket from Vladikavkaz to Moscow on 2 August 2014, the day after Kuashev’s body was found.

Also on 29 July, Denis Machikin and Roman Matyushin, both Moscow-based FSB officers likely working at the Department for the Protection of the Constitution, flew into Vladikavkaz. The two had purchased return tickets to Moscow on 30 July 2014. However, they didn’t use them – and changed the tickets to 31 July 2014, the day when Kuashev disappeared. The partial airline booking data we have reviewed does not show conclusively if they flew on that day or, like Ospiov, rebooked the once more for the following day.

Machikin and Matyushin’s FSB department

We know that these two men are FSB officers because they travel on joint airline bookings with other known FSB officers, including Alexey Alexandrov. We believe they are most likely from the Department of Protection of the Constitution because members of the FSB poison squad work with and travel only with operatives of this unit. Furthermore, we have tracked parking and traffic fines of these people to near Vernadskogo 12 in Moscow, where this unit is headquartered.

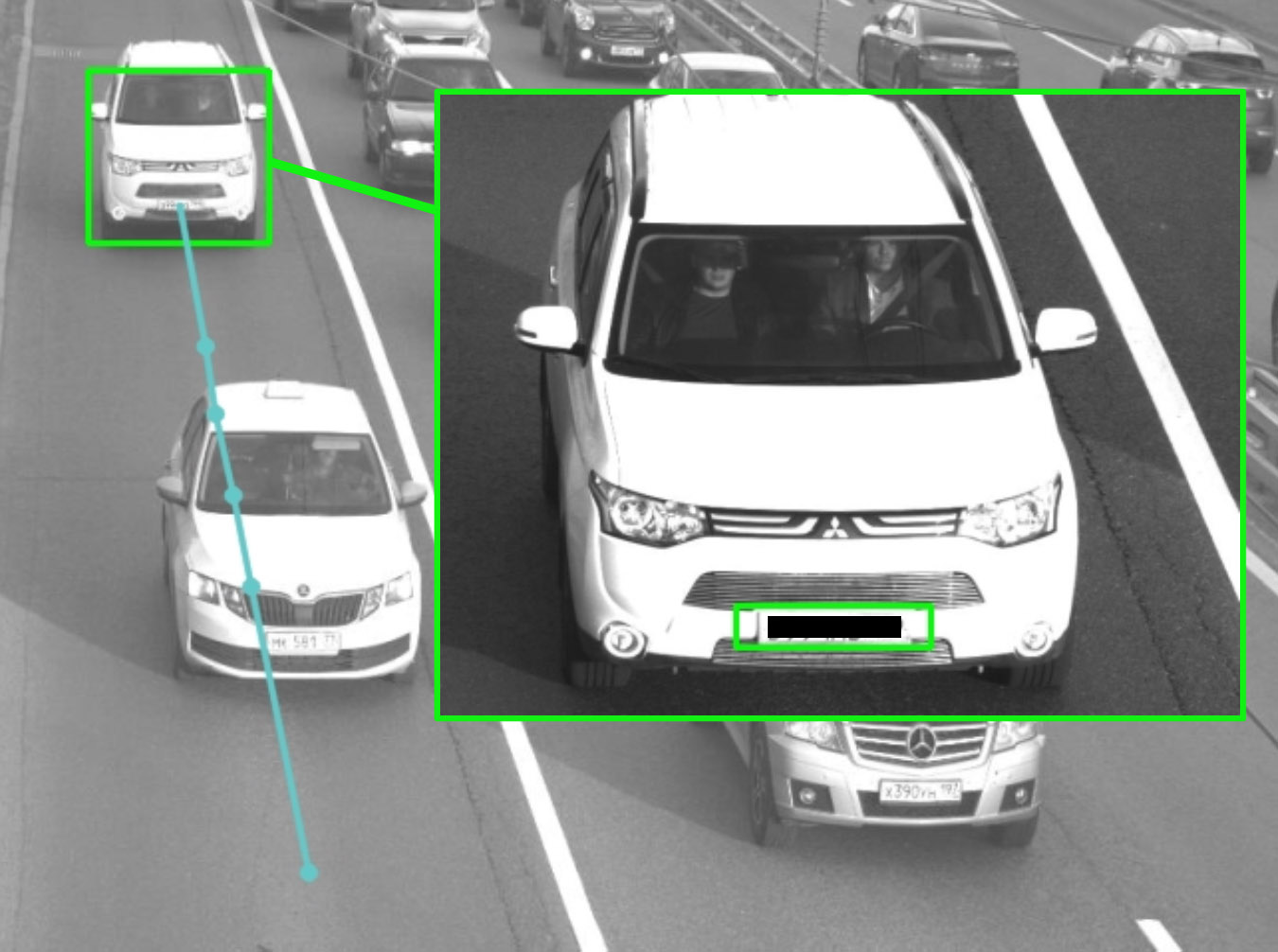

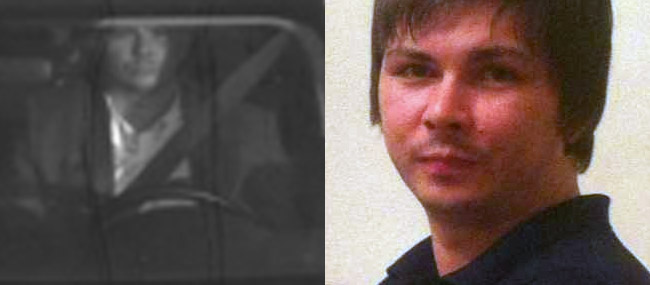

Denis Machikin, born 1985, a photograph from a speed camera. Open source traffic violation data shows Machikin has more than 60 unpaid fines in the last two years alone, totaling over Euro 2000. Russian security operatives routinely do not pay traffic violation fines.

A comparison with a cropped photo of Denis Machikin found on the VK social network page of his wife.

Following Kuashev’s disappearance, potentially crucial evidence in the case vanished, in a way that appears consistent with the modus operandi of the FSB squad. As Konstantin Kudryavtsev stated in the phone call with Navalny, the unit ensures that all security cameras are taken offline during their operations.

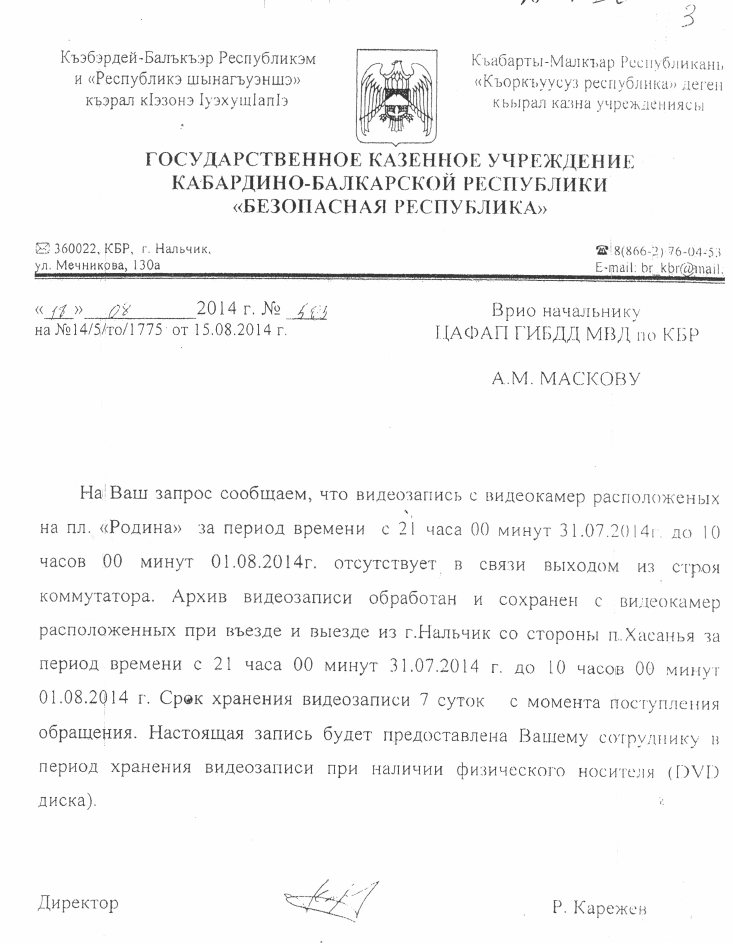

In Kuashev’s case, all security cameras from the square in front of the Rodina theater, where he had gone to watch his mother’s play, had been offline during the evening of his disappearance due to a technical error, or as described in the below document a “commutator malfunction”.

A letter from the traffic police department to investigators explaining that the security cameras on the Rodina square had been offline during the period 21:00 on 31 July 2014 until 10:00 on 1 August 2014 due to a technical malfunction

Translated letter

In response to your request, we write to inform you that video recordings from the video cameras located on Rodina Square from the period between 21:00 on 31.07.2014 to 10:00 on 01.08.2014 do not exist, due to a communication failure from the [network] switch. Archival footage from video cameras located at the entrance to the city of Nalchik in the direction of Khasanya village between 21:00 on 31.07.2014 and 10:00 on 01.08/2014 has been saved and developed. The storage period for recordings is seven days from the date of their request. The recording in question will be provided to your co-worker during the storage period, in DVD format.

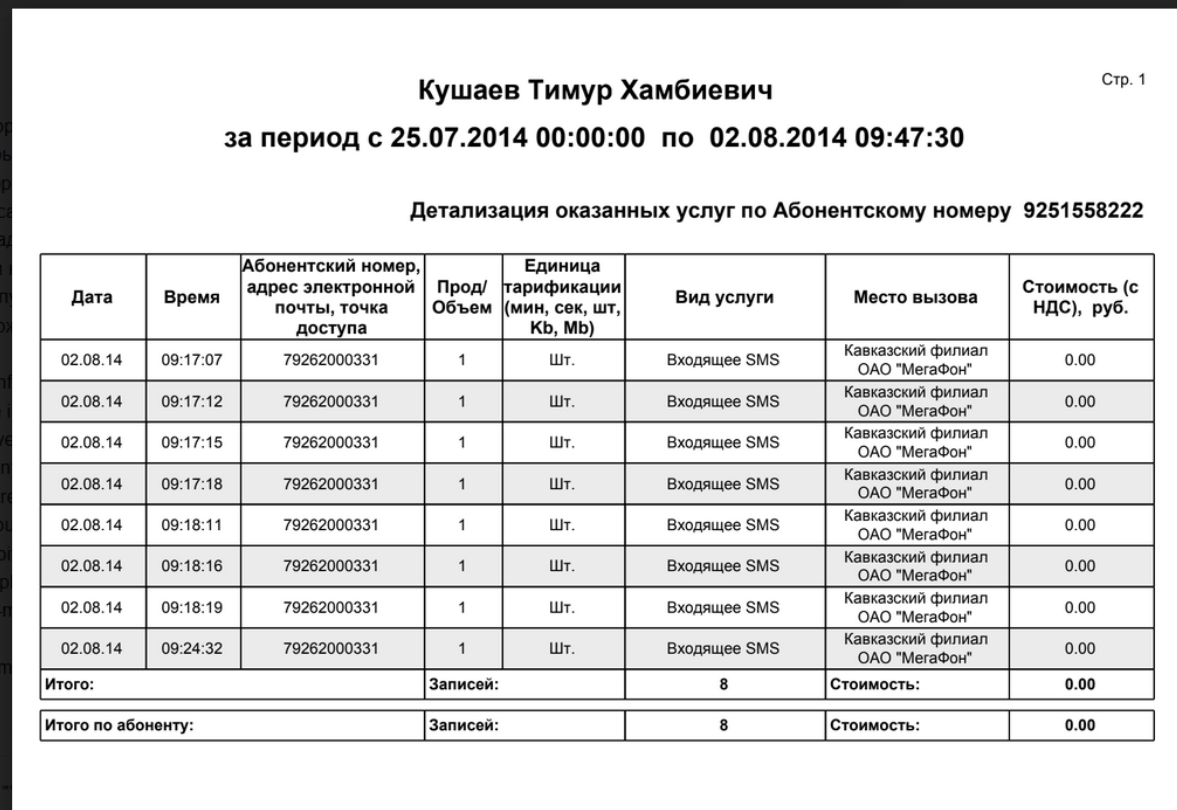

Director, R. Karezhev

On 2 August, a day after Kuashev’s body was found, his friends and colleagues were able to obtain a full extract of call records from his mobile operator for the week beginning 25 July until 2 August. The call records showed zero activity – neither phone, text, nor internet – prior to 2 August 2014. The complete absence of communication through 1 August is contradicted by the activity for 2 August 2014 which shows eight incoming spam messages (a relatively regular occurrence on Russian mobile phones). The alternative hypothesis that this phone had been switched off, and only turned on again on 2 August 2014, is contradicted by phone data of other telephone numbers, including of a human rights activist from Dagestan who told our investigative team that they spoke and texted with Kuashev on that number in the days prior to his death.

If a cleansing of Kuashev’s call activity had been undertaken by the mobile operator, this could not have reasonably happened without the intervention of the FSB who have overarching control over telecommunication operators. Russian mobile operators are obliged to preserve complete call records and provide them regularly to an FSB-supervised repository.

The Perfect Crime

Following the death of Timur Kuashev, tissue and blood samples were initially tested for toxins locally in Nalchik. However, the local hospitals’ laboratories do not have the capability to perform mass-spectrography, the best-practices method to identify toxins and narcotic compounds in blood and urine samples, or other complex analysis. Tissue samples were sent to Moscow for a follow-up analysis.

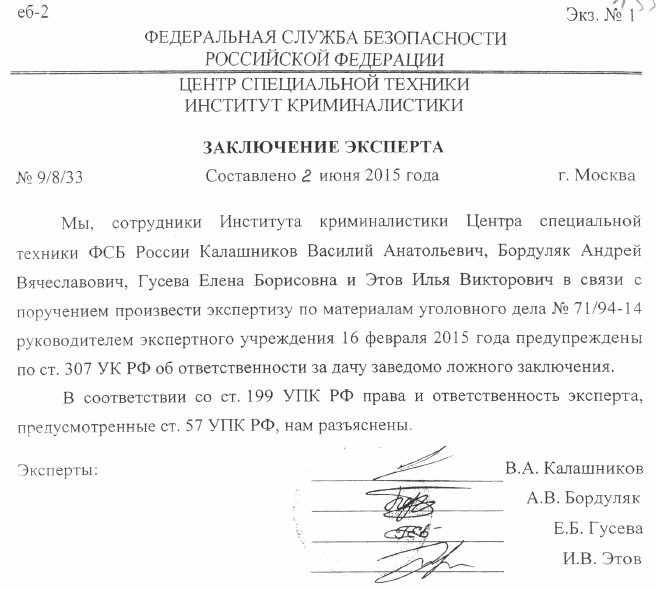

The main expertise report conducted in Moscow confirmed the absence of any toxic substances in traces of Timur Kuashev’s blood, which had leaked on to his shirt around the injection area. This served as a key factor in closing the criminal investigation into his death.

However, the analysis was performed by none other than the FSB’s Criminalistics Institute: the same unit that employs the clandestine poison squad, including Dr. Alexandrov, Osipov and Kudryavtsev. The expert report was signed by Vasiliy Kalashnikov: the same FSB expert who – as admitted by Kudryavtev in his tell-all phone call – was supervising the evidence-purging efforts in Omsk after the poisoning of Alexey Navalny. As we have previously determined, the poisoners of Alexey Navalny worked under the guise of this exact institute. In the case of Kuashev, this would have allowed the poisoners to investigate, and ultimately cover up their own assassination operation.

Translated letter

CENTRE FOR CRIMINAL TECHNOLOGY OF THE INSTITUTE OF CRIMINALISTICS

Expert testimony

Drafted 2 June 2015, city of Moscow

No 9/8/33

We, employees of the Institute of Criminalistics of the FSB’s Centre for Special Technologies, Vasily Anatolyevich Kalashnikov, Andrey Vyacheslavovich Bordulyak, Elena Borisovna Guseva and Ilya Viktorovich Etov, in connection with instructions from the director of the expertise department to carry out an expert analysis on materials relating to criminal case No. 71/94-14, have been forewarned of the criminal liability for knowingly providing false testimony under article 307 of the criminal code of the Russian Federation. In accordance with Article 199 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the rights and responsibilities of those providing expert testimony, provided for under Article 57 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, have been explained to us.

A leading global expert on chemical weapons who requested to remain unnamed reviewed the full expertise (available here) and opined that:

“The analysis performed was rather basic. GC-MS and LC-MS with standard searches against standard libraries and no further specified in-house database“. Obviously, if the compound used was intentionally developed to avoid detection, the analysis would have missed such compound because it would not be in any of the “official” libraries”

The Lezgin Activist from Dagestan

On 24 March 2015, in the town of Kaspiysk – a coastal suburb of Makhachkala, the capital of Russia’s southernmost autonomous Republic of Dagestan – local residents found the body of Ruslan Magomedragimov, an activist of the local Sadval (Unity) movement. The Sadval movement had been created in 1990 and had as its ultimate mission the “creation of national statehood for the Lezgian nation”. Lezgins are an ethnic group of just under a million people, who have their own language and are dispersed between the Russian region of Dagestan and neighbouring Azerbaijan.

Magomedragimov had phoned his friend at noon and agreed to meet him at a festival that celebrates the Lezgian language later that day. He did not make it to the meeting – his body was found just after 2 pm. His car was parked in a courtyard about 400 meters from where his body was found. According to Magomedragimov’s friend, Islam Klichkhanov, the dash cam was removed from Magomedragimov’s car, and two of the three phones he had on him were missing. Investigators who arrived at the crime scene found another person’s fresh shoe prints in the car.

The initial conclusion by the investigators was that Magomedragimov died of heart failure. However, a coroner who conducted a post-mortem on the victim reportedly challenged this conclusion, saying Magomedragimov had a perfectly healthy heart and that the death appeared to have been the result of asphyxiation. At the same time, there were no signs of violence on the victim’s neck or body. The preliminary investigation however ignored this input and concluded that Magomedragimov had died of heart failure.

At the same time, Magomedragimov’s relatives claimed that after receiving the body for burial, they noticed two dots resembling the traces of a syringe needle on his neck. On the insistence of relatives, tissue samples were sent for analysis for the presence of toxins in his body. We could find no public reports of the results of this analysis and we have been unable to reach members of Magomedragimov’s family to obtain details. However, the leader of the Sadval movement publicly stated that he was convinced that Magomedragimov had been killed as a result of his activism. Regional media drew parallels between the deaths – including the traces of injections – of Magomedragimov and of Timur Kuashev a year earlier.

The similarities between Magomedragimov’s death and that of Kuashev also extended to the overlapping presence of members of the FSB poison squad.

Like in the case of Kuashev, poison squad members Ivan Osipov and Konstantin Kudravtsyev traveled to Makhachkala in the period before Magomedragimov’s death: Osipov visited the town twice in January 2015, and Kudryavtsev traveled to Makhachkala two weeks before the death – just as happened in the 2014 Kuashev case – staying in the region from 11 to 16 March.

Just four days before Magomedragimov’s death, on 24 March 2015, Ivan Osipov flew into Vladikavkaz – a four-hour drive from Kaspiysk. He stayed in the region for six days and left back to Moscow two days after the presumed poisoning.

While the datapoints and travel overlaps in Magomedriagimov’s case are fewer than those in Kuashev’s, they are not sufficient for a standalone conclusive assessment that he was killed by the FSB poison squad. Yet the strikingly similar circumstances surrounding the deaths of these two activists from the North Caucasus, including claims around the use of injections to induce death broadly mis-attributable to heart failure, are notable.

As a Sadval activist. Magomedragimov defended the rights of the Lezgin people and supported the idea of an autonomous “Lezgistan” based on unification of Russian and Azerbaijani Lezgins. Despite the pacifist nature and innocuous tactics of this organization, it is conceivable that it was seen as a separatist movement that carried long-term disruptive risks. Exactly a year after Magomedragimov’s death, the leader of the Sadval movement, Nazim Gadjiev, was found killed at his home in Makhachkala with knife wounds on his body. No suspects in the murder were named.

The Kremlin-Friendly Anti-Corruption Fighter

On 16 November 2019, Nikita Isaev posted a selfie on VK as he sat inside a train that was about to depart from Tambov, a city roughly 500 km south-east of Moscow. Isaev was leaving for home after another day of hard work: meeting with local residents disenchanted with local corrupt politicians and regional mini-oligarchs.

He had been doing this for just over а year as head of his self-styled “New Russia“ movement, and had always managed to tread the fine line between criticizing regional or second-tier Moscow politicians and never angering the federal government. While positioning his movement as independent and anti-establishment, Isaev continued to support the Kremlin’s main policies and President Putin personally, and to attack Russia’s foes, foreign and domestic, including Alexey Navalny. The latter was ironic given that some domestic observers called Isaev “the new Navalny”, alluding to the fact that he appeared to copy Navalny’s regional corruption-bashing style, and even bore a visible resemblance to him. Unlike Navalny, Isaev had unimpeded access to national TV channels and was a frequent commentator on topics ranging from consumer protection, US politics and the war in Ukraine. Many believed that Isaev had been a “spoiler” political project developed by his former mentor Vladislav Surkov, former aide to Putin and the architect of Russia’s political system of “sovereign democracy”. Isaev’s role, it was supposed, was to splinter and weaken Alexey Navalny’s political following, while attacking Surkov’s political enemies inside the Kremlin. He had even been made advisor on regional development for A Just Russia – one of the “systemic” opposition parties in the Russian Duma that routinely supports the government’s policies.

This made his sudden death on 16 Novemeber during the nine-hour train ride to Moscow even more puzzling. In the description of his former aide and love interest Alina Zestovskaya, Nikita Isaev woke up just after 1 am and went to the toilet. He was gone for a long time, and when he came back, he was slouching and holding his abdomen, as if someone had punched him. The last words he could utter before he collapsed to the floor in convulsions was “I got poisoned, I think”.

Zhestovskaya called the train conductor, but he said there was no point in stopping the train – it was speeding through endless forests, and the next possible stop didn’t even have a paramedic’s facility. By the time the train got to the next station – more than an hour later – Isaev had lost his pulse and his fingers and lips had turned blue. The doctors who came on board at the train station declared him dead on site.

Upon arrival in Moscow, blood samples from Nikita Isaev were sent for laboratory tests. Before the results came in, he was cremated – as he had wished, his family told our investigative team. The laboratory analysis showed no traces of toxins in his blood – and his death was declared the result of a heart attack. Few of his followers and sympathizers believed this explanation, as evidenced by the hundreds of incredulous phone calls to a radio show with Alina Zhestovskaya – after all, he was a healthy, fit 41-year-old, and he himself had said he believed he had been poisoned. Despite all that, Zhestovskaya told our investigative team she believes he died of a heart attack, and believes people who claim he – or Alexey Navalny – were poisoned are simply spreading conspiracies.

Nevertheless, our interviews with family members and friends of Isaev suggest that in the months before his death he was restless. A friend of his living abroad, who requested anonymity, told us that in June 2019, Isaev discussed with him possibilities to move his family out of Russia. Isaev did not inform him of any specific threats, but, in his words, during their June meeting “was not his normal self”. Two people close to Isaev, who also requested anonymity, told us that shortly before his death he began suspecting that Alina Zhestovskaya had been “assigned to watch over him”, and that he was intending to get rid of her. Zhestovskaya told us she initially met Isaev accidentally on a train and worked for him on a voluntary basis due to shared beliefs in fighting corruption. She was playing an increasing role in his movement, and after his death briefly took over his role in the organization.

Reconstruction of the FSB Operation

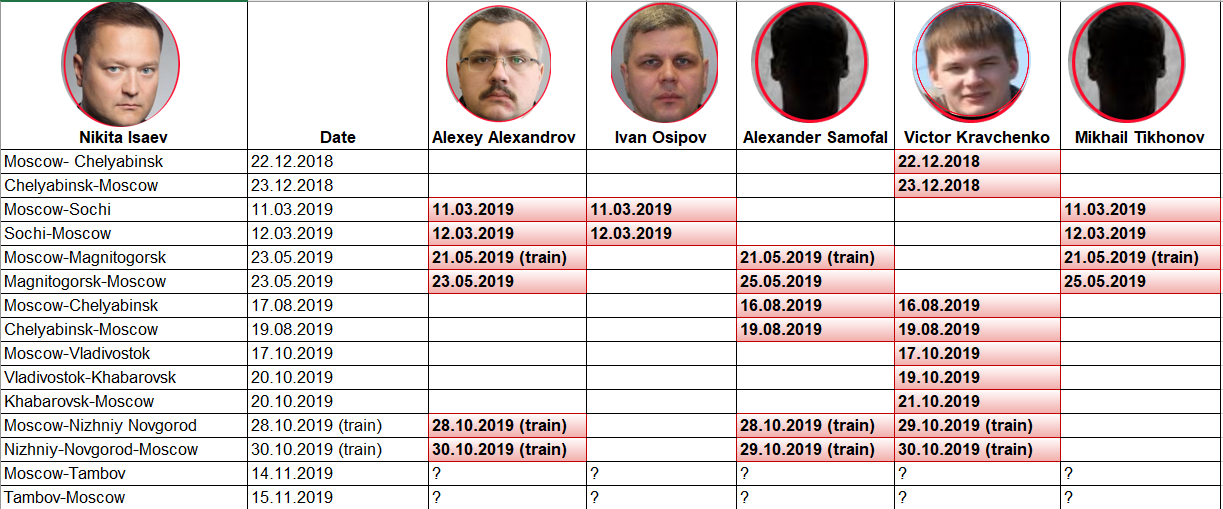

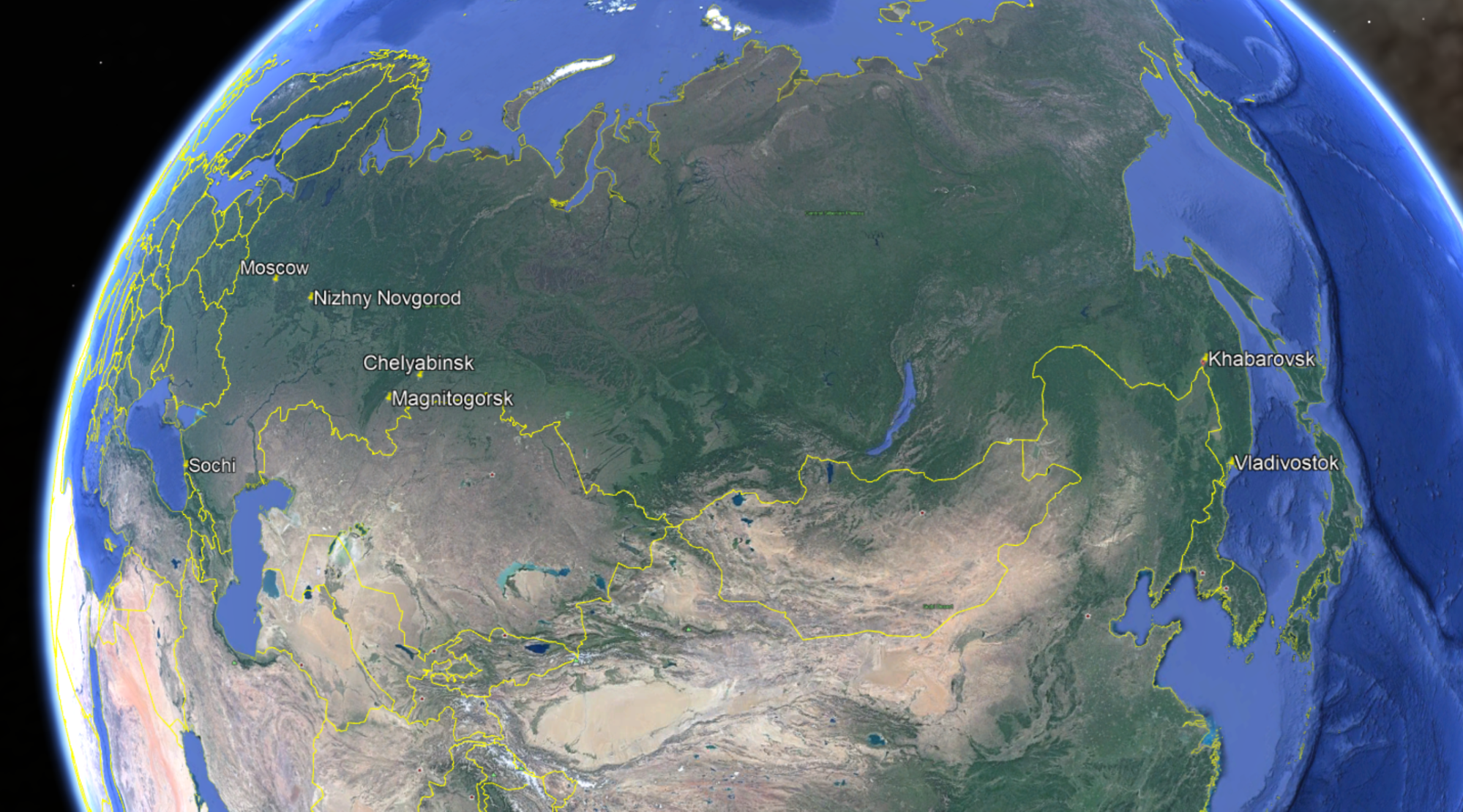

As a result of crowdsourced analysis of the travels of 10 of the known operatives from the FSB poison squad, contributors noted the overlap of two 2019 trips by the FSB’s Dr. Alexey Alexandrov and Nikita Isaev – whose campaign trips were diligently detailed on his VK account. These overlapping trips were to the remote city of Magnitogorsk near the border with Kazakhstan, in May 2019, and to Nizhny Novgorod in October 2019, a month before Isaev’s death.

These two overlaps were statistically significant but not sufficiently convincing for a hypothesis of FSB’s involvement in his death. However, these two trips provided us with a lead to identify other co-passengers of Alexandrov based on an analysis of flight and train passenger manifests. Those new three names in turn provided us with a larger set of trips which we could then compare once more to Isaev’s travel data. We also obtained additional data for Isaev’s travels from several offline (incomplete) ticketing databases, which broadened his own travel dataset beyond those trips known about from his VK account. Based on this, we again tried matching his trips and the broader set of known FSB operatives.

The result was a picture of at least five FSB operatives linked to the Criminalistic Institute’s poison squad, tailing Nikita Isaev for nearly a year before he died.

The table above shows that FSB operatives tailed Isaev to and from seven destinations around Russia, on a total of 13 flight or railway journeys. The actual number of overlapping trips is likely higher due to the fact that Isaev’s travel data is incomplete and, on at least some of the trips, the FSB operatives may have traveled on as yet unknown undercover identities. Furthermore, we have not yet identified all members of this FSB unit. However, even with only these seven (with thirteen segments to the trips) overlaps to destinations strewn across a gigantic territory – and in at least one case, tailing him between two destinations in the Russian far east – the statistical probability of a false positive is close to zero.

Map showing the wide range of locations where the FSB team trailed Isaev, from the far southwest of Russia in Sochi to the Pacific Ocean in Vladivostok. Source: Google Earth

The additional three FSB operatives identified through this operation – Alexander Samofal, Victor Kravchenko and Mikhail Tikhonov – flew during this period or earlier on jointly made bookings with either Alexey Alexandrov or other known members of the poison squad. Thus it can be excluded that they are random, accidental co-travelers. We have not yet determined if the three are operatives of the Institute of Criminalistics or of FSB’s Department for Protection of the Constitution, which, as discussed previously, tend to work in tandem with the poison squad.

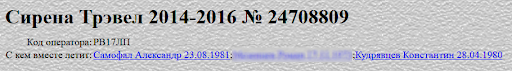

Extract from a flight booking showing Alexandr Samofal flew on a joint booking with Konstantin Kudryavtsev and another operative

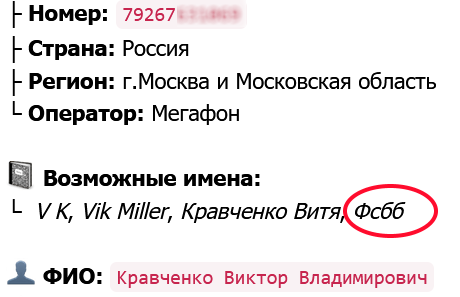

Screenshot from reverse-phone-search app showing Viktor Kravchenko’s number listed with the heading “FSBb”. Kravchenko also traveled on joint bookings with Alexandrov.

It is important to note that the existing travel databases we have consulted do not show that any of these five operatives traveled under their known identities to Tambov during the days Isaev died. This could potentially be explained either by data purging after his death, or by the fact the officers traveled under different identities yet unknown to us. There is no conflicting travel data for these identities – i.e. existing travel data does not suggest they were in other places at the time of the Tambov trip.

Possible Motives

None of the people close to Isaev have a plausible explanation of why a pro-Kremlin, patriotic-minded activist may have crossed the FSB. His conflicts with regional government officials – part of his activism – were deemed as unlikely motives: Isaev’s friends and family are convinced that if the Kremlin authorities were unhappy with any part of his activity, a simple hint would have sufficed for him to change course.

One source familiar with Isaev’s work who requested anonymity suggested that he may have been targeted by FSB due to the fact that he was a Surkov protégé. Vladislav Surkov, who fell in and out of grace with the Kremlin over the past decade and resigned from his position as advisor to President Putin in early 2020, is known to have had a fraught relationship with the FSB. However, to this source it appeared unlikely that the FSB would resort to murder in the course of its ongoing confrontation with Surkov. Thus far, known motives for assassinations through poisoning have been limited to charges of terrorism, treason, or serious threats to the regime such as in the case with Alexey Navalny.

A possible explanation might lie in Isaev’s frequent trips overseas that accelerated in the year prior to his death. Isaev traveled abroad frequently, with multiple trips to Germany, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Israel, Turkey, Latvia and the United States in 2019 alone. In fact, Nikita Isaev had previously purchased tickets to fly with his family to Miami on 5 December 2019, just three weeks after his demise. It is conceivable that the FSB may have suspected him of planning to defect; a suspicion that may have been fueled by his discussion with contacts about moving his family out of Russia.

Conclusion

The three cases described in this report presents further evidence that the clandestine FSB unit that tailed and, later self-admittedly, poisoned Alexey Navalny in August 2020 is in fact an effective state assassination program, and not simply a political intimidation tool.

The findings also shed light on the broad arsenal and application of techniques that this unit employs, as well as on its apparently selective approach to using seemingly simpler and fast-acting poisons on less public targets (such as an injected poison with Kuashev) versus use of more sophisticated toxic substances with deferred onset of symptoms on likely higher-value targets (such as Novichok with Navalny) who are subject to greater public scrutiny.

These case studies along with the previously known Navalny assassination attempt also provide a sample of the breadth of possible motives that determine a person’s placement on the FSB’s presumed kill list. It appears that in addition to the presumed involvement of this unit in the poisoning of perceived threats (such as the insurgent leader Doku Umarov, along with political figures who pose perceived threats to the central regime, such as Alexey Navalny) this FSB unit also appears to preemptively target opinion leaders and human rights activists in volatile regions.

While the case with Isaev requires more information before a motive can be identified, it does open the possibility for either the weaponization of the FSB’s poison squad for the resolution of conflicts inside Russia’s political elite, or – as is already known from the poisoning of Sergey Skripal – the use of security services to assassinate perceived traitors.

This investigation was conducted in collaboration with Der Spiegel and The Insider. Christo Grozev served as the primary researcher for Bellingcat, with contributions from Pieter van Huis, Aric Toler and Yordan Tsalov.

We would like to thank our many volunteers who reached out over social media for their invaluable assistance in making this research possible.