Putin Chef's Kisses of Death: Russia's Shadow Army's State-Run Structure Exposed

Yevgeny Prigozhin can be described as the Renaissance man of deniable Russian black ops. An ex convict who served time for robbery, fraud and involving a minor in drinking and criminal activity, he began his legitimate business career in the 90s as a St. Petersburg restaurant owner and later as caterer for the Kremlin.

Today, his official business is a sprawling catering consortium that provides meals to millions of Russian soldiers, policemen, prosecutors, hospital patients and schoolchildren in return for hefty tax-funded payments estimated at at least $3 billion since 2011. Yet his unofficial operations fit the profile of an authoritarian state’s shadow security apparatus: industrial-scale manufacturing of fake-news, intimidating journalists, election interference, political engineering, and actual clandestine military operations. Prigozhin was famously indicted in the US over the role of his troll factory in trying to influence the 2016 elections in favor of Donald Trump, a charge he flatly denies to this day. His troll-factory generated one of the largest known online disinformation campaigns, churning out 71,000 tweets aimed at presenting Russia’s version of events in the downing of flight MH17. The same troll infrastructure posted thousands of messages promoting Brexit. Prigozhin has also been linked to Kremlin-friendly political engineering across dozens of African countries while he has been sanctioned by the US over his funding for the Wagner Group, an unincorporated private military company with a history of clandestine operations in Eastern Ukraine, Syria and several African countries. It was most recently accused of placing booby-trapped mines around Libya’s Tripoli. The EU has yet to sanction him or his metastatic group over any of his activities.

Now, a long-running investigation by Bellingcat, The Insider and Der Spiegel has uncovered that Yevgeny Prigozhin’s disinformation, political interference and military operations are tightly integrated with Russia’s Defense Ministry and its intelligence arm, the GRU. Prigozhin’s private infrastructure – along with that of other government-dependent entrepreneurs, like Kostantin Malofeev – it appears serves as a deniable veneer and a round-tripping money laundering channel for government-mandated overseas operations.

At the same time, Prigozhin’s attempts to take initiative and leverage his crucial role for personal gain has also resulted in embarrassment for the Kremlin. During what appears to have been a failed operation to capture oil-wells from SDF and U.S. Armed Forces in the Syrian province of Deir ez-Zor in February 2018, Wagner mercenaries suffered heavy casualties in a U.S. counter-attack that left the Kremlin scrambling for an appropriate reaction (which never came). On another occasion, Russian mercenaries have posted self-incriminating videos into semi-public online groups, such as this gruesome chronicle of the torture, murder and beheading of a Syrian civilian near Palmyra. The following video has graphic content:

Our investigation team spoke to a number of current and former employees who worked in Prigozhin’s overseas interference and political engineering projects. They told us of widespread lack of motivation, infighting and alcohol-driven dysfunction at these operations, more indicative of bloated, government-funded junkets than a private operation with clear goals and outcomes.

We have also identified a key figure serving as a liaison between Prigozhin’s influencing operations in Africa and the Russian Defense Ministry. According to documents seen by our investigation team and corroborated by interviews, this person has been in overall command of Russian paramilitary operations in Africa, including at the time when three Russian journalists investigating Prigozhin’s operations in the Central African Republic were murdered, as well as while Western journalists were tailed and harassed. This key person appears not to be on the radar of Western intelligence or law enforcement agencies, as he enjoys unrestricted travel in Europe based on multi-entry Schengen visas.

This investigation is based on a review of leaked email archives belonging to employees working for Prigozhin’s group of companies. Some of these archives have already been subject of investigations by independent Russian media while others have been obtained exclusively by the investigative team. We have validated the authenticity of the messages and contained documents through interviews with several former and current employees of Prigozhin’s overseas influencing operations.

Prigozhin’s (un-)Deniable Link to the Kremlin: Digital Breadcrumbs

Yevgeny Prigozhin’s links to the Kremlin and Russia’s Ministry of Defense (MoD) are hard to disguise given his companies’ prominent role as catering providers to the Kremlin and the Russian military. However, the intensity of his communication with the top echelon – both within the Kremlin and the MoD – is difficult to explain away simply based on the “catering” relationship.

Bellingcat has analyzed Prigozhin’s telephone records for an eight-month period spanning late 2013 and early 2014. The records were obtained from hacked emails of Prigozhin’s personal assistant leaked in 2015 by the Russian hacking collective Shaltai Boltay. The emails contained telephone billing records for his company Concord Consulting & Management, and we were able to identify Prigozhin’s personal number among the list of corporate numbers based on a reverse-phone-number-search app. This period coincided with Prigozhin’s troll-farm operations transitioning from a purely domestic political tool – used primarily to trash opposition figures and independent journalists – to an ambitious international operation with more and more efforts allocated to foreign interference operations – first in Ukraine, and later globally.

During this period, Prigozhin spoke or texted with practically the entire leadership of the Presidential Administration Office, along with a number of senior figures at the FSB, in the Federal Protective Service (FSO) and the Ministry of Defense. In particular, he called and texted Dmitry Peskov – President Putin’s adviser and spokesperson – a total of 144 times. He also called – or was called by – Anton Vayno, Putin’s chief of staff, a total of 99 times. He communicated 54 times with Igor Diveykin – Putin’s deputy chief of staff overseeing domestic politics, arguably a job description that doesn’t include the logistics of food catering. Prigozhin spoke more than 25 times with Lt. General Alexey Dyumin – Putin’s ex head of security and – at the time of the calls – deputy director of GRU who supervised the Crimea annexation. He also spoke at least twice in person with Sergey Shoigu, Russia’s minister of defense, while email traffic showed more planned in-person meetings with him. Prigozhin also spoke 31 times with Shoigu’s number two, the Deputy Defense Minister Bulgakov in charge of army logistics. Prigozhin also spoke 3 times with Yury Ushakov, Russia’s former ambassador to the USA and Putin’s senior advisor on foreign policy issues.

The interactive graphic below shows some of the key government figures that Prigozhin communicated with with during this period. By hovering over or clicking a name, a pop-up will show further in formation on the person and the number of communications during the fairly brief 2013-2014 period. Double-click a section (e.g. Ministry of Defense) to only bring up individuals in that grouping.

While Prigozhin’s companies were indeed catering providers both to the Kremlin and to the Ministry of Defense, it is not plausible that this service relationship would have required such frequent, high-level communication on either side along with members of state intelligence services – especially given the purely political or military mandates of his counterparts.

The Virtual Reality of Wagner

The Wagner Group – which does not exist on paper – got its name from its purported founder and commander, the elusive and camera-shy Dmitry Utkin, who – thanks to his obsessive fascination with the history of third Reich – had received the nom-de-guerre “Wagner”. Col. Dimitry Utkin, born on 11 June 1970, was a career officer who had seen first-hand military action in both Chechen wars. In the early 2000’s, as the military phase of the second war subsided, he was moved to the town of Pechory near the Estonian border, where he served out the next ten years as commander of GRU’s Second Spetsnaz Brigade. According to his former wife, he found it hard to adapt to civilian life and always longed to be back on the battlefield.

It is not exactly clear when Utkin retired from the army but in 2013 he reportedly already worked for a little-known Hong-Kong based private security company called Slavonic Corps (archived website in English and Russian here). Slavonic Corps in May 2013 advertised online for “24 to 45 year old …former Spetznaz employees.. having the necessary training in military action… for work abroad on business trips of 3-6 months“. The only known deployment of this private military company (PMC) – in Syria in late 2013 – ended up with the mercenaries losing a battle with Al-Qaeda-linked militants, and then falling out with their Syrian paymasters over who was to blame. Utkin’s name did not feature among the known command structure of Slavonic Corps, and the person in charge of the Syrian operation – based on witness statements – appears to have been Vadim Gusev, deputy director of yet another Hong-Kong-incorporated, but St. Petersburg-run PMC, the Moran Security Group. The Syrian mission ended up in shambles, with Russia’s FSB arresting many of the returning mercenaries and charging them with “unlawful warfare abroad“, the requisite crime for mercenary work which is illegal in Russia.

By early 2014, however, many of the people who were involved with the Slavonic Corps were back in demand. As Russia needed quick – and deniable – military presence in Crimea, the concept of a private, legally unincorporated, shadow army employing skilled soldiers with prior combat experience, appeared to be the perfect solution.

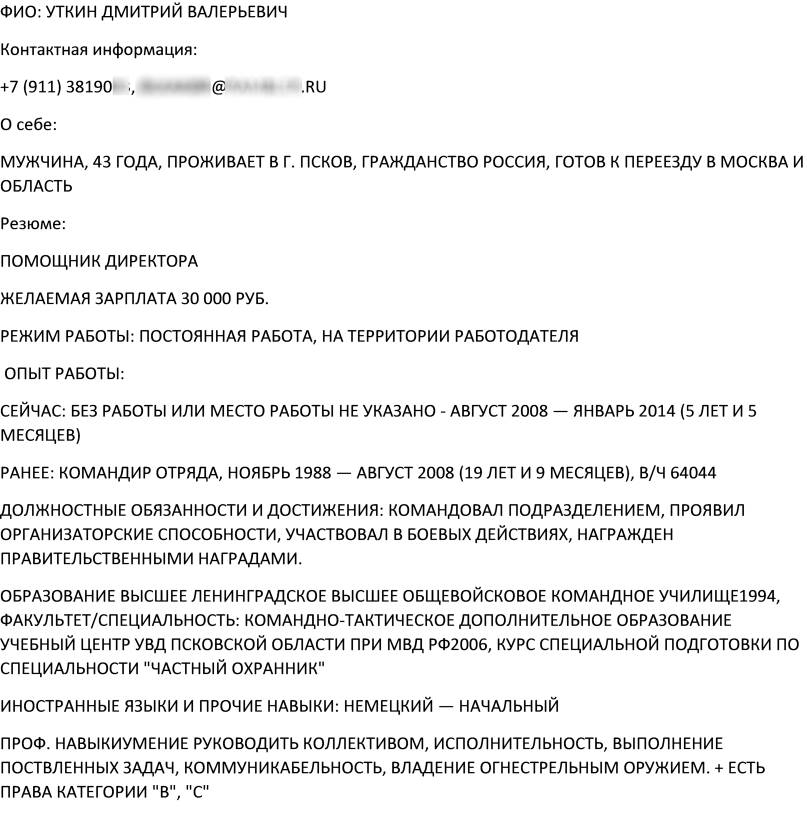

Beginner’s German and Gun Skills For Hire

From the data we have reviewed it cannot be determined who came up with the initiative for the Wagner Group. However, we have found open source data that strongly suggests Col. Dmitry Utkin was not in the driver’s seat of setting up this private army, but was employed as a convenient and deniable decoy to disguise its state provenance. In an archived, offline copy of a job application website, we discovered a job-search CV that appears to have been posted by Utkin himself in late 2013 and which was archived in January 2014. The job application, which contains a telephone number that we have confirmed belonged to him at the time, says Utkin currently lives in Pskov, is currently looking for a full-time job as a deputy general director, and is ready to move to Moscow. His asking salary is RUB 30,000 per month (just under $1000 at the time). He states he was a unit commander at the (GRU) military unit 64044 between 1988 and 2008, but leaves a gap in his career since 2008, suggesting he may not have been operationally involved with that unit since then. Indeed, he mentions a professional re-training program he undertook in 2006, which landed him a private guard certification.

Utkin also goes on to mention his military awards and describes himself as a “team-leader”, “good communicator”, and “performs set tasks successfully”. He also says he speaks beginner’s German and is good with weapons.

Based on the timing of this resume – posted as late as a few months prior to Wagner Group’s critical role in the invasion of Ukraine – it is implausible that Utkin was anything but a hired gun to provide the “private army” project a public-facing legend.

Archived job resume of Dmitry Utkin, circa January 2014

By March 2014, Russian “mercenaries” were already in Ukraine, and the Wagner legend had been born. After the unit’s successful initial deployment in Crimea and Donbass, in 2015 the unit received a permanent training base at a top-secret GRU facility at the village of Molkyno, near Krasnodar airpport. Wagner’s largest international deployment so far has been in Syria, where according to a former Wagner officer, at least 2,500 mercenaries were deployed, under the GRU’s and FSB’s supervision, to assist pro-government Syrian forces.

According to a journalistic investigation by the Russian website The Bell, the idea of creating a deniable, “off-balance” private army – and entrusting its logistical operational aspect to Yevgeny Prigozhin – came from high-ranking officers from Russia’s Defense Ministry, after being impressed with a 2010 presentation by Eben Barlow, the founder of the South-Africa-based PMC “Executive Outcomes”. Three different sources are quoted as saying that initially Prigozhin objected to such a high-risk role, but that given his pre-existing service relationship with the Defense Ministry – which provided the cover operation with both an alibi and an existing support infrastructure – he did not have the option to refuse it.

Whether or not the “Wagner Group” was the brainchild of the Russian military establishment or of Prigozhin himself, multiple digital breadcrumbs corroborate the linkage between his operations and the private military company. These include joint air-travel bookings between Prigozhin employees – including the head of his trolling operation – with known Wagner officers, and the use of at least three companies controlled by Prigozhin as payroll providers for Wagner mercenaries.

GRU In The Driver’s Seat

While Dmitry Utkin has been widely presented as the front man and “principal” for the Wagner PMC, there is ample data suggesting that his role was more of a field commander, and that the “Wagner Group” mercenaries are integrated in an overall chain of command under central Kremlin control with its military intelligence (GU/GRU) apparatus.

In phone intercepts published by Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU), Utkin is heard reporting to a man named Oleg Ivannikov on the progress of military activities in Eastern Ukraine at the time of the battle for Debaltseve in February 2015. Bellingcat has previously identified Ivannikov as a senior GRU officer who helped procure at least one Buk missile system for the militants in Donbass in the days before the downing of MH17. In another intercept from the same period, Utkin is heard reporting to Andrey Troshev, a former police colonel from St. Petersburg. In the call, Utkin despondently complains to Col. Troshev that he has lost count of how many casualties his unit has suffered, and begs to be recalled back to Russia for fear of being killed himself by his own soldiers. A third intercept from early 2015 shows Utkin taking instructions and coordinating the mercenaries’ work directly Maj. General Evgeniy Nikiforov, then chief of staff of the 58th Western Army.

It is clear from the context of the calls that Utkin appears to be subordinated both to GRU’s Ivannikov and overall to the Russian military command, and that Col. Troshev is his superior within the so-called Wagner Group. Not surprisingly, in March 2016 it was namely Col. Troshev who was awarded the Hero of Russia Award for his role as commander of the Wagner Group engaged in supporting government forces in Syria in 2015 and 2016.

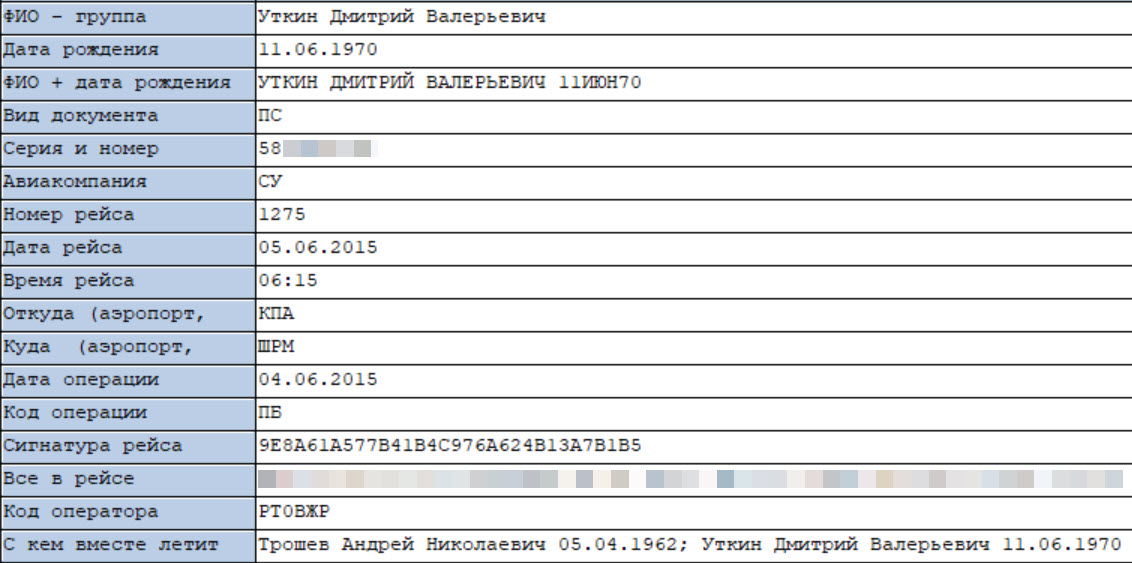

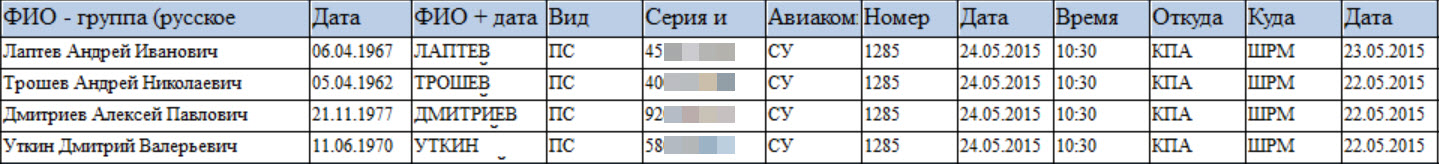

Bellingcat has also identified joint airline bookings between Wagner’s commanding officers – including Utkin himself – and active GRU officers. On at least one occasion, Utkin flew in the company of both Troshev and “Andrey Ivanovich Laptev” – the fake identity of GRU’s Gen. Ivannikov.

Dmitry Utkin and Andrey Troshev as co-travelers on a flight between Krasnodar (near the Wagner base) and Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport, on 5 June 2015. The two being co-travelers (the field “С кем вместе летит”) indicates their tickets were booked together.

Andrey Laptev (cover identity of GRU officer Oleg Ivannikov), Andrey Troshev, Aleksey Dmitriev (Wagner commander), and Dmitry Utkin on the same flight from Krasnodar to Moscow. There were only ten passengers on this flight, four of whom were tied to Wagner and the GRU.

The Kremlin’s deniability of any formal links to the Wagner Group became famously impossible after Utkin was spotted during a video broadcast from a Kremlin reception held on 9 December 2016. After initially denying any knowledge of Utkin’s existence, Putin’s press secretary Dmitry Peskov ultimately acknowledged he had attended the Heroes of the Fatherland gala event at the Kremlin. Subsequently a VK account focused on mercenary activities published a photograph in which Putin is seen standing next to four heavily – and apparently recently – decorated Wagner officers at a Kremlin function. While there is no public information on when Utkin received his latest award, a Russian website tracking military honors reported that Col. Troshev was given Russia’s highest military honor, the Hero of Russia award, plus a Gold Star order for his military services as a “volunteer” in Syria. The award was reportedly granted through a secret decree signed by Putin on 17 March 2016. The fact that Utkin was not presented with that award (he is seen wearing four Bravery orders, a less exclusive military honor), plus the standing arrangement supports the hypothesis that Utkin is of lesser relevance within the so-called Wagner Group than Col. Troshev.

Vladimir Putin with Col. Andrey Troshev (second from left), sporting a fresh Hero of Russia award, and Col. Dmitry Utkin (far right), wearing four Bravery orders.

Clone Wars

Following this unplanned public appearance, Dmitry Utkin “Wagner” was never seen or heard of in public. A phone number previously used by him is now disconnected. However, travel records reviewed by us show that he continued making rare trips between St. Petersburg and Krasnodar through late 2019.

Despite Dmitry Utkin’s apparent withdrawal from active operational involvement with Wagner activities, his name has not stayed out of focus. A few months after the publication of the Kremlin photograph, in November 2017 a person bearing Utkin’s exact full name was appointed as CEO of Yevgeny Prigozhin’s flagship catering company, Concord Management and Consulting, a company with nearly $20 million in unconsolidated revenues and controlling a group of companies with nearly 10 times that turnover. When approached by Russian media to comment on Concord’s presumed links to the Wagner Group, Prigozhin responded that “the appointment of Dmitry Utkin – who has never before held any position within our group – is a private personnel decision”, and said he had no knowledge of the existence of a private military company which, he said, “is not even legal under Russian law”.

Prigozhin’s coy response disguised the fact that the Dmitry Valeryevich Utkin in fact appointed as CEO was not the Wagner Group commander. In fact, this Dmitry Utkin was created just a month earlier – through a legal name change (permissible in Russia) of a little-known St. Petersburg resident, eighteen years younger than the original Utkin and having only three months of prior management experience running his own startup company: Alexey Karnaukhov. This fact can be established by the common tax-payer number for the two names – Karnaukhov registered a company under his original name in March 2017, while the cloned “Utkin” was registered as Concord’s CEO under the same tax number in November 2017. On 1 March 2018 – just after the Deir ez-Zor Wagner fiasco – Prigozhin removed the freshly-created Dmitry Utkin from the CEO position and appointed himself instead.

Prigozhin went through this cloning exercise a second time: in early 2018, a former St. Petersburg convict with no prior business experience, Alexander Anufriev, underwent a legal name change, and once again, legally become a Dmitry Valeryevich Utkin. The age difference between the new, third Utkin and the original flagship was only two months, suggesting he may have been more apt to be passed off as the original “Wagner” Utkin. As reported by Russian media, in May 2018 this freshly cloned Utkin incorporated four companies, some of them showing indirect links to Prigozhin’s group. All of these companies were de-registered by 2019. Current Russian debtor databases show that both Utkin clones have unpaid, court-adjudicated debts to third parties, in the case of the latter Utkin – incurred under both his original and new identities.

It is not clear what Prigozhin’s rationale was for causing people to undergo legal name changes to that of the Wagner Group’s public face, and in the first case, flaunting Utkin’s appointment for such a short period of time. Russian media have speculated this may have been a trolling stance of defiance after the US placed both him and Utkin under sanctions over their role in the Ukraine military conflict.

The Colonel is Gone. Long Live the Colonel!

In 2018 and 2019, western and Russian media began reporting on a growing presence of Russian political strategists in various African countries, offering to provide electoral support – including cash, advice and personal protection – to Russia-friendly candidates. An investigation by the independent Russian website Proekt, based on leaked internal documents from a Prigozhin corporate unit “African Back Office”, claimed that as of 2019 Prigozhin had political advisors working in twenty different African states, and had interest in another nineteen. According to Proekt’s analysis of the leaked documents and follow-up interviews with current or former employees, the tasks and scope of work vary greatly by country. In some countries, like Mozambique and the Central African Republic (CAR), the lead role is played by military mercenaries. In others, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Zimbabwe and Madagascar, there were only political strategists, often boosted by the presence of Russian “bodyguards”. In Chad and Benin, Prigozhin’s people work with politicians close to the armed Muslim group Seleka. In some countries, like the CAR and Mozambique, Prigozhin already had business interests in addition to political interference and paramilitary presence.

According to sources interviewed by Proekt, in 2019 Col. Dmitry Utkin had been planning to travel to Rwanda with Valery Zakharov, a Russian security advisor to the President of the Central African Republic. This trip was reportedly cancelled at the last moment. By early 2019 Dmitry Uktin was over-exposed, both due to his presence at the Kremlin gala and through the US sanctions imposed on him. This may have resulted in his withdrawal from the African campaigns.

However, at the same time a different Russian colonel with no media footprint began popping up at different African locations where Russia had dispatched political strategists or security advisers. The colonel, who was known only by his presumed first name “Konstantin”, was spotted initially in Madagascar during the period before the country’s presidential elections in November 2018. He was initially assigned as campaign security chief to an early Russian favorite – Pastor Mailhol of the Madagascar’s Church of the Apocalypse. Mailhol told the BBC that the Russian political strategists who had initially persuaded him to run for president – and had given him suitcases of cash along with a personal bodyguard – ultimately pulled out “Konstantin” from his campaign when a different front-runner emerged. He said they later assigned the Colonel as bodyguard to Andry Rajoelina, who went on to win the election.

The Pastor refused to pull out.

He’d been hearing rumours.

And his Russian bodyguard, Konstantin, had been transferred to the campaign favourite. pic.twitter.com/FDV06LniFM

— BBC News Africa (@BBCAfrica) April 10, 2019

“Konstantin” (right), a personal body-guard provided by Russian strategists in September 2018 to an early Russian favorite in the presidential elections. Photo: Screengrab from BBC AfricaEye report.

Pastor Mailhol and the Colonel on the campaign trail in Ambiolobe on 22 October 2018. Photo exclusively obtained by our investigation team.

Madagascar was not the only African country where “Konstantin” has appeared. Leaked emails from employees of Prigozhin’s “African Back Office”, reviewed by our investigation team, show that the same person referred to in correspondence by his nom-de-guerre “Mazay” was stationed in the CAR in the summer of 2018, and returned there after the Madagascar elections. “Mazay” first arrived to the CAR in early July 2018, approximately three weeks before the murder of three Russian journalists on 30 July just outside the town of Sibut. The three journalists had arrived to investigate the role of the Russian mercenaries in the exploitation of local mineral resources. Investigative Journalists digging into the case have found evidence that points to possible Wagner involvement in the murders, but both the CAR and Russian authorities have shown no willingness to investigate this case further.

“Konstantin”, “The Colonel”, “Mazay”

Leaked back-office emails reviewed by our investigation team do not identify the Colonel by his real name, and only refer to him as “Mazay”. From the context of the correspondence – which only relates to his deployment in the CAR – it is clear that the Colonel was the most important Russian figure on the ground in the republic, and that Russia’s military advisor to the CAR’s president was taking instructions from him. Prigozhin had his own team on the ground in Africa – approximately fifteen individuals with social media, political consultancy or information security backgrounds, all working for a unit referred to in correspondence as “Project Continent”. However, these people all appeared to be taking instructions on ideological matters, countering media leaks and all military matters from “Mazay”. Documents in the emails show that while Valery Zakharov was formally Russia’s military advisor to the CAR’s president, important questions of military relevance were always directed to “Mazay”, who was widely seen by Prigozhin’s team as a representative of the Ministry of Defense, and/or the Kremlin in general. Email exchanges among employees describe “Mazay” as the only person in the CAR who talks with Prigozhin without fear and as an equal.

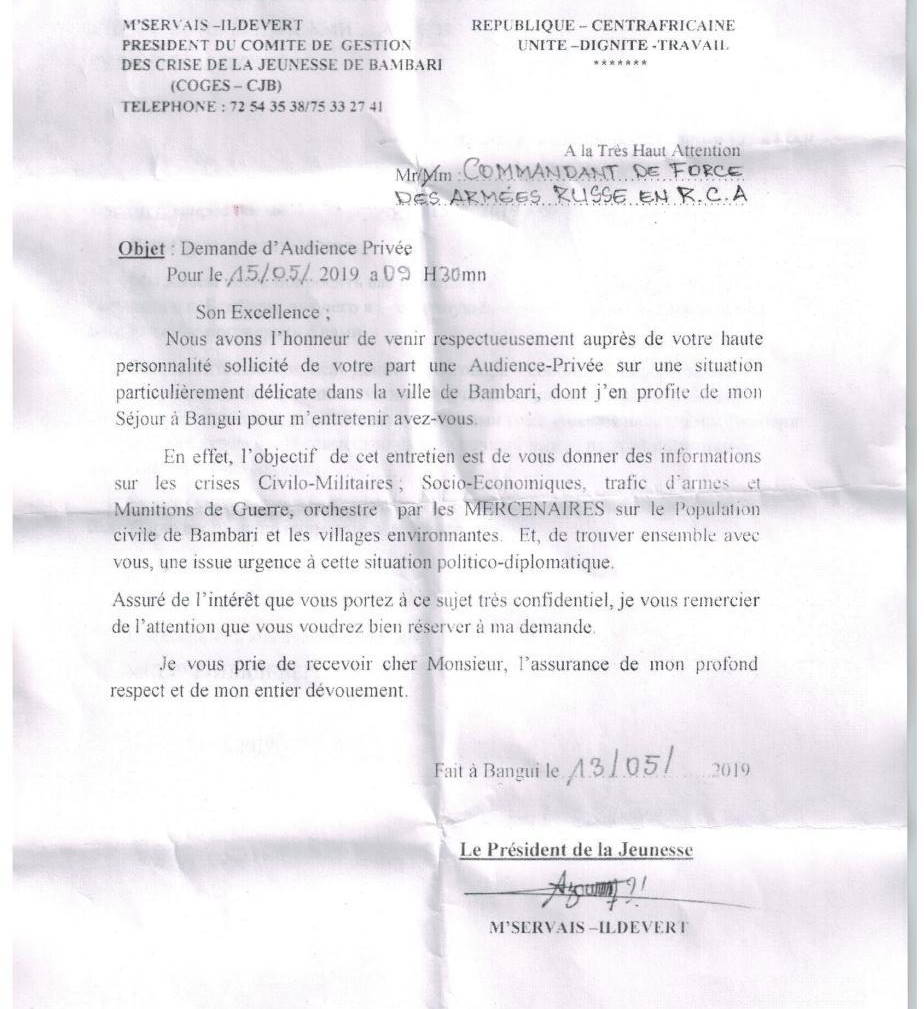

For example, one email contains an attached scanned letter from local provisional authorities in the town of Bambari addressed to the Commander of the Russian Armed Forces in the Central African Republic. The letter, dated 13 May 2019, requests an urgent and private meeting in order to “discuss a particularly delicate situation in the town of Bambari”. The local official, M’Sarvaise-Ildevert, further writes that he would like to pass the Russian military command information about the economic, social and weapons-proliferation crisis caused by “the Mercenaries” on the local population. The author implores that an urgent solution be found jointly during such meeting.

Notably, the email containing the letter says the Russian military command had forwarded to “Mazay” for further action.

It is unclear from the letter if the author requests Russian help to deal with local armed groups, such as the Seleca rebels active in the area, or to raise issues caused namely by Russian mercenaries. Just three months prior to this letter, the United Nations had requested CAR authorities address reports of torture of local Bambari civilians by Russian mercenaries or regular armed forces, including an incident in which a local resident had been strangled with a metal chain and had his finger cut off during interrogations. It is clear, however, that an issue originally referred to the official Russian military command deployed in the CAR was delegated for further action to “Mazay”. This example shows once more the tight integration between the Russian military and the hybrid operations fronted by Prigozhin – including political engineering in Africa, as proven by the role of “Mazay” in the Madagascar election campaign.

Identifying “Mazay”

“Mazay”, also known as “The Colonel” and “Konstantin”, has not been previously identified by any publication and was not identified by name in any of the African back-office correspondences. It appears that his identity was not in fact known to Prigozhin’s Africa-focused employees. “Mazay” was careful to never be captured on camera without his sunglasses on. which made identification via facial recognition search impossible.

In the absence of open-source data to proceed with our investigation, and in order to identify “Mazay”, we obtained and analyzed Russian telephone billing records of Valery Zakharov, Russia’s military advisor to the CAR’s president. Two of the numbers he communicated with in 2019 belonged to a St. Petersburg-based company with the name Military-Security Company “Convoy”. This company was incorporated on 15 January 2015 with an inordinately high share capital – 100 million Russian rubles (approximately $1.5 million USD at the exchange rate of the time). “Convoy” lists its main activity as “providing military security services”. Despite its impressive share capital, the company officially employed only three individuals in 2019, and had a turnover of just over $70,000 USD. The newly-registered company has maintained its cash reserves at over 100 million rubles since its incorporation and to the time of this article’s publication.

The company’s founder was another St. Petersburg legal entity: The St. Petersburg Cossack Association “Convoy” which also boasts “military security services” as its activity. This organization was incorporated in 2009 and has five individual shareholders, one of whom is also the CEO of the Military Security Company “Convoy”. His name is Konstantin Aleksandrovich Pikalov, born on 23 July, 1968.

A search in reverse number-search apps showed that the numbers called by Zakharov and registered to Convoy were in fact used by Konstantin Pikalov.

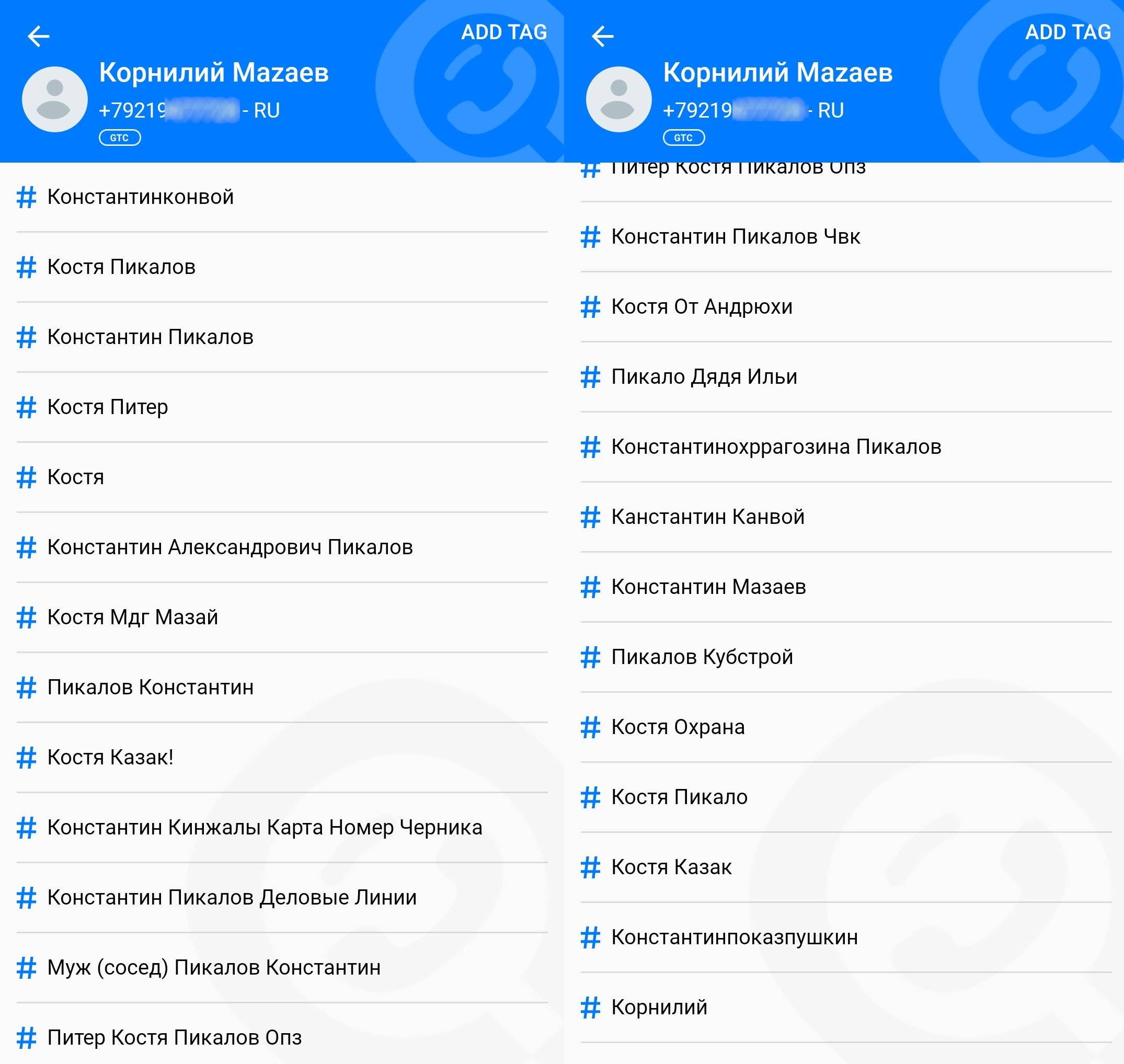

What’s more, the reverse phone number search app GetContact, which is extremely popular in Russia, provided a number of different ways in which Pikalov’s number had been entered in various users’ contact list. GetContact, along with other apps like TrueCaller, vacuum up their users’ contact books and will publicly list the various names inputted into its users’ phones for an associated phone number. This practice provides researchers with a plethora of names, nicknames, functions, mnemonic devices, and so on, unbeknownst to both the app user and the phone number’s operator. Many of these results displayed entries you would perhaps expect from someone’s cell phone contacts, such as “Konstantin Pikalov” or “Kostya Pikalov”, but also include more personalized names, such as “Ilya’s Uncle Pikalo” and “Neighbor husband Pikalov Konstantin”.

As seen in a screenshot of the GetContact results below, a common thread among many was the use of Mazay, or Mazaev, as his moniker. This finding corroborated our hypothesis that Konstantin from Madagascar and Mazay are the same person. The entries also shine more light onto the nature of Pikalov’s background. He was listed by some as “Pikalov – Private Military Company”, “Konstantin the Cossack”, “Konstantin MDG Mazay” (MDG being a likely reference to Madagascar), and “Ragozin’s Bodyguard”. The latter is likely to be a misspelled reference to Dmitry Rogozin, ex-Deputy Prime Minister of Russia and current head of its space program. Rogozin was sanctioned by the US and EU over his role in the Crimea annexation and war in eastern Ukraine.

To validate our hypothesis that Konstantin Pikalov and the “Colonel”, aka “Mazay”, are the same person, we obtained a passport photo from a source with access to the Russian passport database. While it is not possible to conduct a proper forensic facial comparison given the partial visibility of his face on the African photos, when considering all of the other evidence, we found a sufficiently convincing match of the visible facial features, including ears, nose and skull shape, to conclude that this is the same person.

Who is Konstantin Pikalov

Based on a review of leaked offline databases, until at least 2007 Pikalov served as an officer at Russia’s military unit 99795, located in the village of Storozhevo near St. Peterburg. Russian open sources list this particular base as an experimental unit of the Ministry of Defense, tasked, in part, with “determining the effects of radioactive rays on living organisms”. Following his retirement, Pikalov continued to live on the military base at least until 2012, and ran a private detective agency. In 2016 he ran for office in local council elections in the district of the military base on behalf of the Just Russia, a pro-Kremlin political party. His participation was denied by the Central Election Committee for unknown reasons. However, this may have been the result of a criminal record, as his name is listed in a Central Bank blacklist with a note that he was “a suspect in money laundering”. Pikalov’s current criminal file is blank, which can mean either that the suspicion did not result in actual criminal charges, or that the records have been purged.

Based on reviewed travel records, in 2014 and 2017 Konstantin Pikalov traveled several times to destinations near the Ukraine border, sometimes on joint bookings with known Wagner officers – including with Vadim Gusev, the person who supervised the original Syrian endeavor of Slavonic Corps, and Nikolay Khamatkoev, a known Wagner operative.

“We’re The Dancers”

Pikalov’s international electoral experience does not seem to be limited to the African continent. On 27 September 2014, he flew to Belgrade, Serbia and traveled on to Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He returned via Belgrade on 15 October 2014. During this period, which coincided with the re-election bid of the Kremlin-supported President Dodik, a large group of Cossacks arrived to the small country and loitered around the streets for several weeks in full paramilitary attire. The theatrics of this visit were implausible: an all-male group, 144 strong, had ostensibly arrived to dance at a cultural exchange festival. However the trip was widely seen as an effort to interfere in the elections by suppressing an anti-Dodik vote. The spokesman for the group gave interviews in which he, half-smirking, repeatedly denied that the visitors were Russian Spetznaz. The Cossack group left immediately after the successful reelection of Dodik on 12 October 2014. As we reported in 2017, Konstantin Malofeev traveled to Republica Srpska during the same period and was photographed with Dodik on election day.

While we could not find Konstantin Pikalov in photographs from the 2014 events in Bosnia and Herzegovina (most “dancers” shied away from the cameras, as was reported by local media), his co-shareholder in the Convoy Military Security company, Vasily Yaschikov, did post photographs from Banja Luka.

A year after his trip to Republika Srpska, Pikalov took a twenty-day trip to Kazakhstan beginning on 20 June 2015. He also made a number of trips to Finland and Estonia, possibly to justify his freshly-issued Schengen visa.

Col. Konstantin Pikalov, seen getting progressively younger on different passport photos used for various travel documents since 2015

In and Out of Africa

While former employees of Prigozhin’s back office we interviewed on the condition of anonymity told us that “Mazay” was known to have been taken part in military operations in both Ukraine and Syria, we did not find corroborating data in the border crossing or flight records. This, however, does not indicate he did not travel to those destinations, as he would have done so either on military aircraft or by crossing the border with Ukraine illegally.

Pikalov’s first tour in Africa, based on commercial flight records, began on 7 July 2018 with a trip to the Central African Republic by way of Istanbul. It is not clear if and what other countries in Africa he may have visited during this trip, as he returned to Moscow two-and-a-half months later on 28 September 2018 by way of Amsterdam.

He stayed in Russia only two weeks and then returned to Africa for a second tour – this time flying by way of Qatar to Madagascar initially on 9 October 2018. He stayed in Madagascar until at least after the presidential elections in November that year, and returned – likely after spending time in the CAR – to Russia via Paris on 21 January 2019.

Pikalov’s third African tour began on 9 April 2019 and ended on 15 July 2019. During this trip he flew via Qatar and Lisbon, and spent a significant amount of time in the CAR, judging by references to Mazay in the leaked correspondence. His last trip to Africa was the shortest: between 26 November and 7 December 2019. He flew to and back from an unidentified location via Istanbul.

It must be noted that this trip history to Africa may not be exhaustive, as they may exclude flights on military aircraft, which are not subject to the same border-crossing logging as commercial flights.

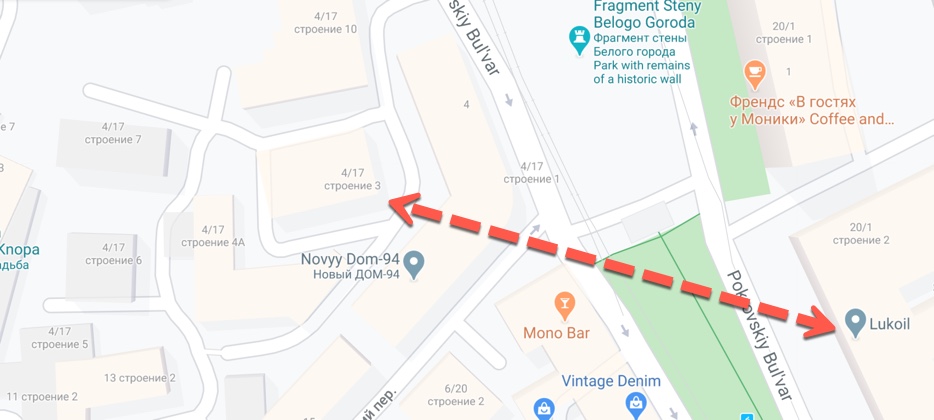

Pikalov’s last known trip was in February 2020. On 12 February he took a two-day trip from St. Petersburg to Pechory. Pechory, a small town of 10,000 near the Estonian border, houses the the GRU’s Second Spetsnaz Brigade.

Flying under the EU Radar

Despite being on the blacklist for money-laundering in Russia, his apparent key role in Russia’s hybrid military-mercenary operations, and interference in elections in Africa and the Balkans, and despite his possible – but not independently investigated – link to the murder of independent Russian journalists, as well as to torture of civilians in Africa, Konstantin Pikalov has been able to traverse Europe unimpeded. In the period 2015 to 2019, Pikalov has received three Schengen visas issued by the Finnish consulate in St. Petersburg, all granted for “tourism purposes”. His latest visa is valid through 16 March 2021. So far he has traveled, on his way to and back from assignments in Africa, via France, the Netherlands and Portugal.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, an arguably more menacing figure in Russia’s hybrid permanent war, is not under any EU sanction. The US indictment against him for fronting the electoral interference in the 2016 US elections has limited his personal travel possibilities. However, his proxies and associates continue unimpeded travel. European businesses continue conducting business with him. Following the US indictment against him and his group of companies, a German business trading with him sent the following email to his secretary:

“From now on, it will be hard to do business with Concord. Please pay future bills from any other unrelated company”

In Part 2 of this report, we will investigate Yevgeny Prigozhin’s history of illegally surveilling, threatening and harassing independent journalists, as well as fabricating false narratives to preempt Russian and foreign media’s attempts to peek into his relationship with the Russian military.

Correction: “This article was amended on 13 January 2022 to reflect the fact that Yevgeniy Prigozhin was not convicted of being involved in child prostitution but was in fact convicted of involving a minor in drinking and criminal activity”.