"V" For “Vympel”: FSB’s Secretive Department “V” Behind Assassination Of Georgian Asylum Seeker In Germany

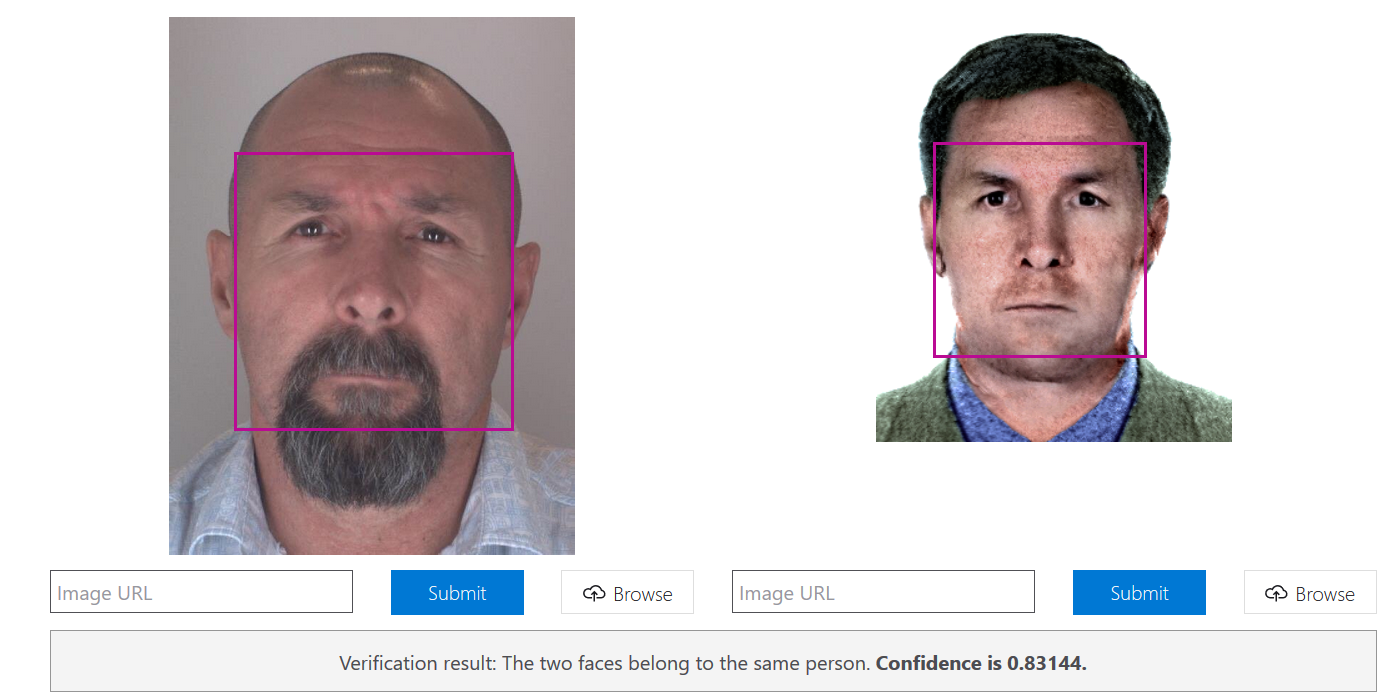

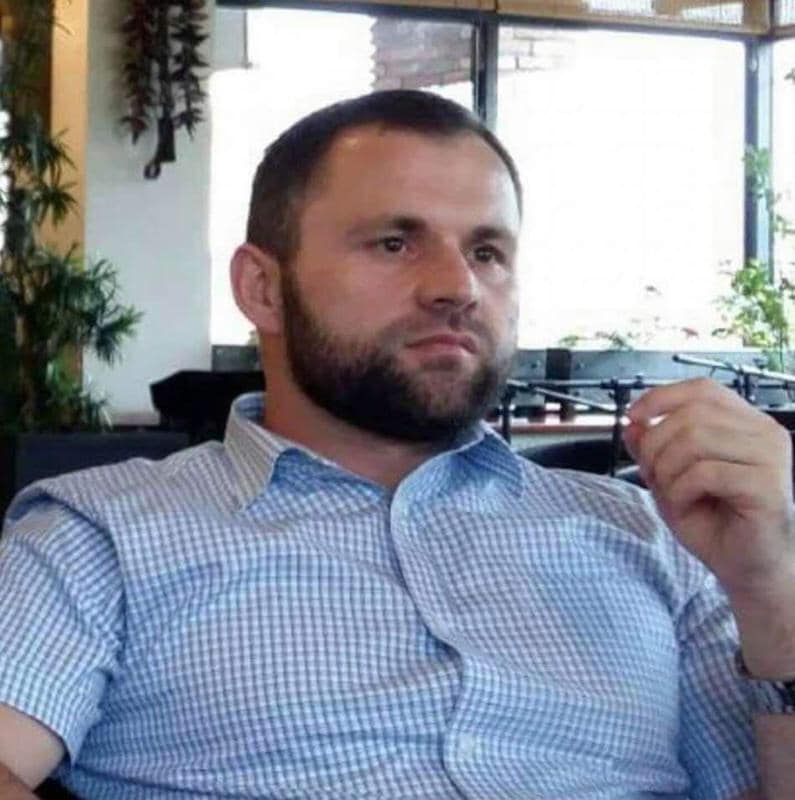

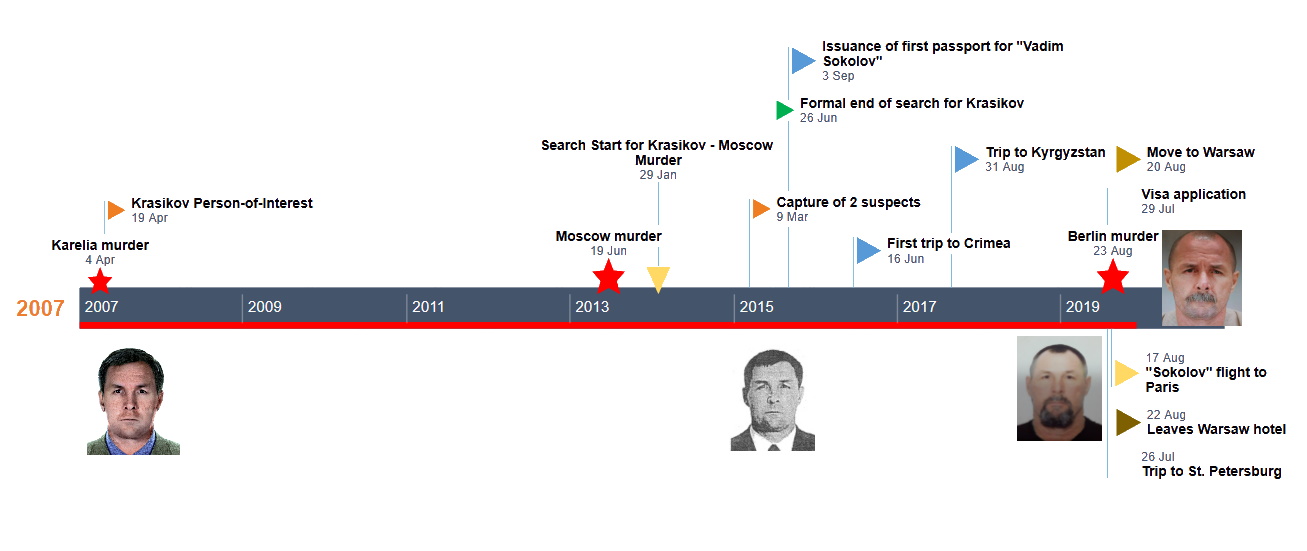

- In our previous investigation of the murder of Zelimkhan Khangoshvili on August 23, 2019 in Berlin, we identified the suspected assassin — who traveled under the fake identity of Vadim Sokolov, 49 — as Vadim Krasikov, 54. We disclosed that Krasikov had a prior criminal history that involved at least two contract killings, once in Karelia in 2007, and one in Moscow in 2013

- We disclosed that as of 2013, Krasikov had been wanted for murder by Russia under an Interpol Red Notice warrant. However, in 2015 the warrant was withdrawn and evidence of his criminal past had been cleansed from Russian databases

- We concluded that the sophisticated procedure of issuing valid documents in the name of a fake persona, along with the full registration of such non-existing person in all government databases, could not have been done without the direct involvement of the Russian State.

A months-long investigation by Bellingcat and its partners, The Insider and Der Spiegel, has uncovered that the assassination of Zelimkhan Khangoshvili in Berlin last August was planned and organized by Russia’s FSB security agency. The preparation for the murder was supervised directly by Eduard Bendersky, chairman of the Vympel Charitable Fund For Former FSB Spetsnaz Officers, and other senior members of the fund, apparently to provide a veneer of deniability. However, we have determined that essential support for the operation — both for training the assassin and for issuance of false identity papers — was provided directly by the FSB and on the grounds of the FSB’s so-called Center of Special Operations.

In addition, we confirmed that both the FSB and Russian police were aware of the true identity of the detained killer but chose to lie to the German authorities by denying that “Vadim Sokolov” was a fake identity. Russian authorities also attempted to scrub all public data relating to the killer’s true identity, as well as data linked to his immediate family.

This investigation conclusively establishes that the main security service of the Russian state plotted, prepared, and perpetrated the 2019 extraterritorial assassination in Germany’s capital. Alternative hypotheses linking the murder in criminal groups, to Chechnya’s ruler Ramzan Kadyrov, or even to a personal vendetta by rogue former or current security officers, can now be excluded as improbable.

- Face comparison of detained suspect “Sokolov” and Vadim Krasikov

- Funeral of victim in Pankisi, Georgia. Photo: Sulkhan Bordzikashvili

- Zelimhan Khangoshvili (photo: his Facebook account)

- Known timeline of Krasikov’s activities preceding Berlin

Preparation For Murder

Phone metadata obtained by Bellingcat shows that the plotting for the murder of Khangoshvili — and the selection of Vadim Krasikov as the assassin — was in the works no later than March 2019. Billing records show that starting in early 2019 and ending just before his trip to Berlin, Krasikov was in frequent communication with as many as eight members of the Vympel Association of Former FSB Spetsnaz Officers, three of whom are in senior positions within the organization. (What is Vympel? Read below). One of the people Krasikov frequently communicated with before his Berlin mission was Eduard Bendersky, chairman of both this veterans association and the Vympel Charitable Fund.

Bendersky and Krasikov spoke by phone at least twenty times in the period of February-August 2019, with the phone calls becoming more frequent in the month before the assassin’s trip to Berlin. Notably, Krasikov called Eduard Bendersky on July 3, 2019, as he was driving back from the town of Bryansk, in western Russia, where, as we previously reported, he received ID documents for “Vadim Sokolov” and registered under his fake identity. Krasikov also called Eduard Bendersky on July 28, the day after he returned from St. Petersburg, where he collected his fake employment papers from a company called ZAO RUST, which he submitted as proof of employment as part of his French visa application. Krasikov’s last phone calls with Bendersky took place on August 13, just three days before he flew to Paris, on his way to Berlin.

What is Vympel?

The special operation group “Vympel” was formed as an elite KGB unit in 1981 with a mandate for overseas subversive operations. Its operational scope included illegal reconnaissance, subversion, kidnappings, freeing hostages, coups d’etat and assassinations of enemies to the state. Vympel training – which took a minimum of five years – involved hand to hand combat, shooting from various weapons, underwater and high-altitude survival skills, medical training, explosives improvisation and all-terrain parachute jumps. Specially modified weapons were produced for Vympel’s needs.

Notably, Spiegel’s sources familiar with the investigation say that the pistol Krasikov used in the Berlin murder was a modified Glock 26 with a replaced, unmarked barrel without a serial number and with a special “cut” permitting a sophisticated silencer to be latched on.

In post-Soviet Russia, Vympel was rebranded as special-ops “Department V” within the FSB, with a mandate to counter domestic terrorism. Its units were deployed in the two Chechen wars as well during key hostage situations in the North Caucasus, such as the Beslan school and Budyonovsk hospital operations. Officially, Department V does not engage in extraterritorial assassinations, but a 2006 anti-terrorism law exempts officers from criminal liability for killings made “during counter-terrorism operations”.

Who Is Eduard Vitalevich Bendersky?

While Eduard Bendersky presents himself publicly as a former FSB Spetsnaz officer and current owner of several private security companies employing ex-Spetsnaz soldiers, he often appears in Russian media as a de-facto spokesman for Department V — the FSB successor to the former KGB Vympel unit which, in his words, has re-profiled itself from overseas subversive operations into domestic anti-terror operations against insurgent groups active in Russia’s North Caucasus region. The security companies Bendersky owns and operates carry the name “Vympel,” with his flagship enterprise being “Vympel-A” — a private security services provider to many state-owned companies which has received government and parliamentary recognition.

Bendersky’s initiatives meander between private and state interests. While he has no official position in government, he bills himself as an aide to a member of the Russian Parliament, and is also chairman of the Russian-Iraq Business Council, a subsidiary of the Russian Chamber of Commerce. The Russian government accorded one of his private security companies exclusive rights to protect Russian oil company’s operations in Iraq.

Eduard Bendersky (left), in his role as President of Russia’s Hunting Association, with President Putin (2012)

In a series of letters allegedly written by disgruntled Russian Spetsnaz officers and sent to Russian independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta in 2003, Eduard Bendersky, who was not a public person at the time, was described as a proxy for Col. General Alexander Tikhonov, hero of Russia and head of FSB’s Center of Special Operations (CSO).

The CSO incorporates FSB’s two Spetsnaz units: Department “A” (formerly known as Alfa) and Department V (formerly known as Vympel). The anonymous letters alleged that Bendersky (who had served in Department V as a relatively junior officer and retired with a rank of senior lieutenant) had been assigned the role of an unofficial proxy for the CSO upon retirement, and ran the “Vympel-A” security company under the guidance and instruction of General Tikhonov. The authors also alleged that Bendersky was a frequent visitor to the highly secured compound of the CSO, and often received highly classified information about ongoing FSB operations that he selectively shared with the media to ensure complimentary coverage of CSO’s actions.

The Novaya Gazeta journalist who published the series of letters from disgruntled Spetsnaz officers, Yuriy Shchekochikhin, died days before the publication of the latest of the three letters outlining Bendersky’s role. His death, which was the result of an unidentified poisoning, was investigated as murder, but ultimately the investigation was terminated due to lack of clues. Shchekochikhin was known for his investigations of both organized crime and FSB.

Indirect confirmation about Bendersky’s ongoing links with the FSB can also be found in travel records reviewed by Bellingcat, which show that in 2016, he traveled on joint flight bookings with Col. Gen. Alexey Sedov, chief of the FSB’s Constitutional Protection Service.

Curiously, Bendersky is also the father-in-law of Maxim Yakubets, FBI’s most wanted hacker with a $5 million bounty on his head. FBI has charged Yakubets with major cyber fraud as head of the Evil Corp organization, and has alleged he has been working for the FSB since 2017.

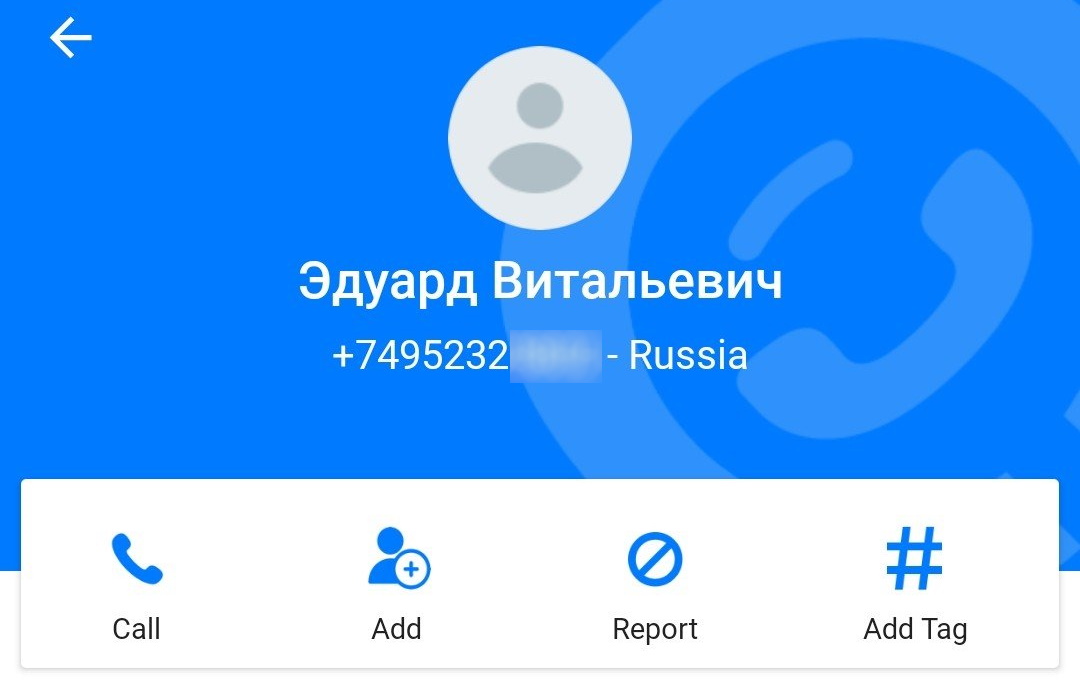

Reached for comment before this publication, Eduard Bendersky told our partner publication The Insider that he had never heard of, or was familiar with Krasikov. He was reached via the same telephone number that communicated with Krasikov based on the analyzed metadata.

FSB’s Direct Role In The Planning

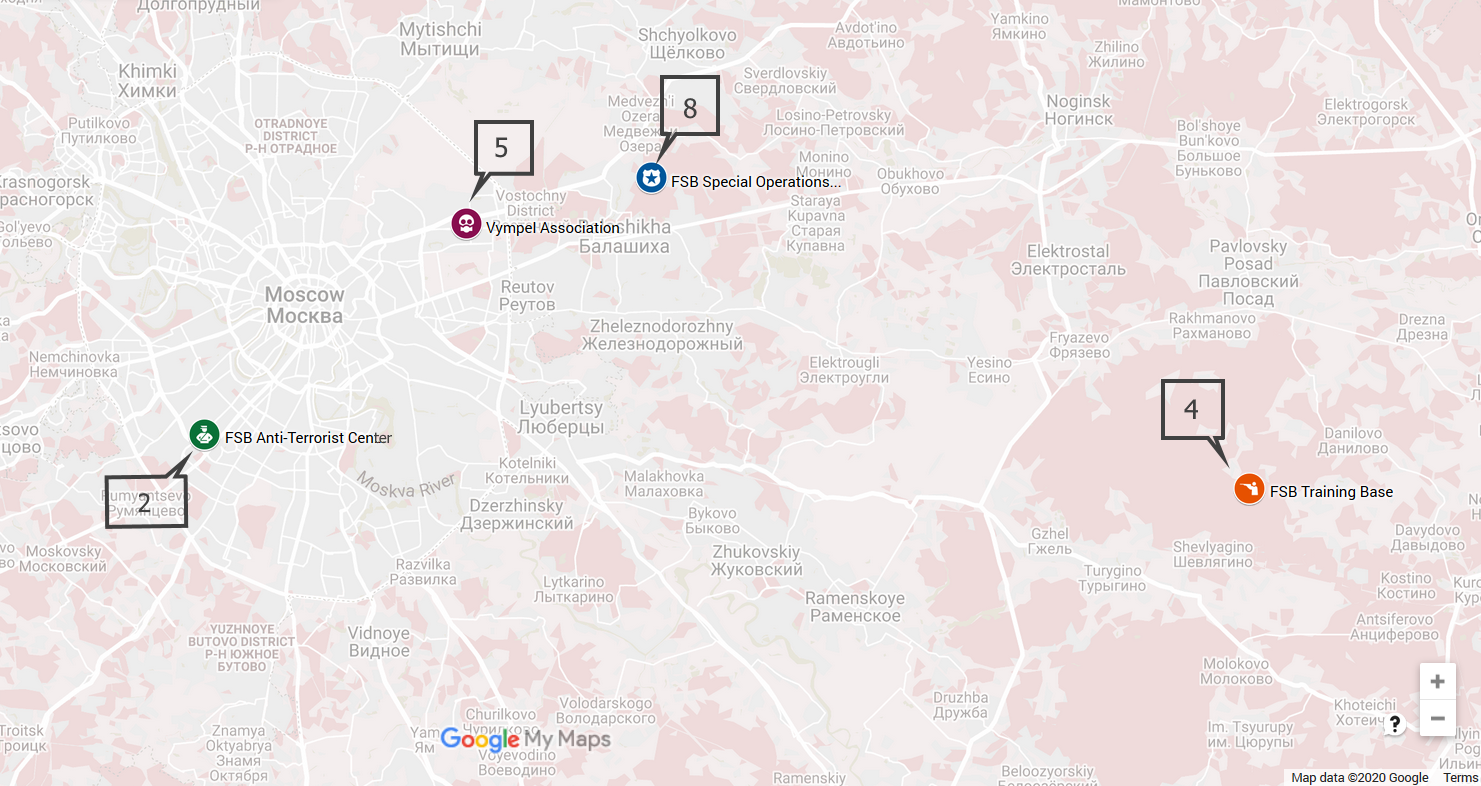

Cell tower connection metadata obtained by Bellingcat shows that Krasikov interacted directly with the FSB in the months preceding the assassination. In addition to his phone connecting to cell towers next to Vympel Veterans’ Association and the Vympel-A security company several times each month, his visits on FSB grounds were no less frequent.

Most frequent were Krasikov’s visits to FSB’s highly secure Special Operations Center in Balashikha, a suburb just outside Moscow. This heavily guarded facility, known as Military Unit 35690, was the original military base for the KGB’s Vympel Spetsnaz unit, and now serves as headquarters for the FSB’s CSO, as well the home-base of the elite and secretive Departments V and A.

- FSB’s Center for Special Operations (Unit 35690)

- Satellite view of the CSO

- FSB CSO

- Main building of CSO

- A container with RPGs that appears to have fallen from a truck near the CSO base. Photographed and uploaded to VK by a teenager living near the base.

Krasikov visited this facility a total of eight times between February and August 2019, the last time on August 8, just days before his trip to Berlin. Cell phone metadata shows that each time he stayed there between two and five hours.

The commander of the FSB’s CSO, which is also known as military unit 35690, is Col. Gen. Alexey Tikhonov, the person who was linked to Bendersky and the the Vympel-A private security company in the 2003 letters to Novaya Gazeta.

Tikhonov received the Hero of Russia award through a secret presidential decree from January 2003, reportedly over his role in resolving the Nord-Ost theater hostage crisis in Moscow in 2002. Tikhonov, along with other FSB leaders, was accused by survivors and relatives of killed hostages in mismanagement of the crisis that resulted in 130 hostage deaths. This case and another hostage situation supervised directly by Tikhonov, which also ended with a shocking high amount of casualties — the 2004 Beslan School Siege — were both referred by relatives to the European Court of Human Rights, with the court concluding in both cases that excessive force had been used by the CSO.

Left, an official CSO poster. Right, CCO’s commander Col. Gen. Tikhonov in 2012

In addition to his visits to the FSO’s headquarters, Vadim Krasikov’s phone also connected on two different days to a cell near FSB’s anti-terrorist center at Prospect Vernadskogo: once in the afternoon on April 2, and a second time in the morning of July 2, 2019. Notably, immediately after his morning visit on July 2, cell phone data show that he drove straight to Bryansk, where his fake identity papers were to be issued.

FSB’s anti-terrorism and analytical center, a high-rise tower on Prospekt Vernadskogo

Krasikov’s most notable trip to FSB’s Spetsnaz facilities, however, was his multi-day visit –— apparently as part of a training session — to a highly secure FSB training facility outside Moscow.

At 7:45 a.m. on April 9, 2019, he arrived at the doors of the FSB Special Operations Center in Balashiha. Shortly before 10 a.m., he drove on, 60 km to the east, to FSB’s Spetsnaz Training Base, which is near the village of Averkyevo.

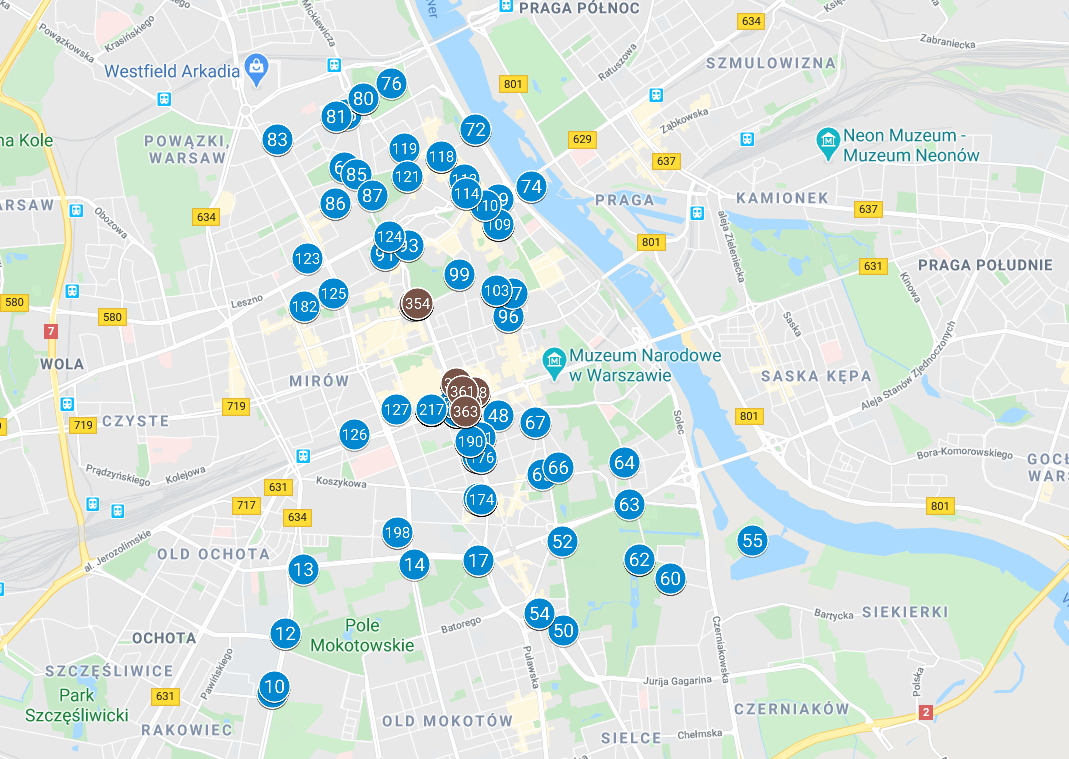

Locations linked to FSB and Vympel frequently visited by Krasikov. Number indicates number of different dates he visited the location

The Averkyevo FSB training base is equipped with multiple interactive shooting ranges, and is intended to train FSB’s Spetsnaz officers in advanced shooting techniques, as demonstrated in this TV report from a 2018 competition among various FSB teams.

Vadim Krasikov stayed at the Averkyevo training base for the next four days, driving back to the Balashiha Special Operations Center, and then on to his Moscow home, on April 12.

Following his latest visible trip to the Special Operations Center on August 8, Krasikov’s telephone was turned off for four days, until August 12. We could not establish his whereabouts during this period, nor could we do it for August 16, the day before his trip out of Russia, when his telephone was also turned off. During these “dark periods” just before his crucial mission, he may have made further trips to the FSO or to its training base at Averkyevo.

Possible Accomplices

It is notable that during the last three weeks before his trip, Krasikov communicated with three people — all current or former members of Department V — who were not among his circle of contacts from the previous months, and were junior to the officers he usually communicated with. It is possible that some of these officers played a supporting role in the Berlin mission. Bellingcat and its partners will continue investigating these people’s possible role in the operation.

Reconstructing The Mission Trip

While Krasikov left his regular phone at his home in Moscow, on August 15, two days before his trip, he activated a separate telephone, registered in the name of his newly acquired fake identity as “Sokolov”. Bellingcat also obtained this phone number’s call logs and discovered that the data had been severely manipulated, with both connection timestamps and cell-tower locations having been altered. However, we were able to reverse engineer the data-altering algorithm and reconstructed a large part of the assassin’s movements on the eve of the Berlin operation.

The “Sokolov” telephone had minimal usage in Russia, and a single phone call was made to a travel agency at 13:46 on August 15. We have matched this travel agent to “Sokolov”’s hotel bookings in Paris and Warsaw.

Like with his regular phone number, no data exists for August 16, implying that on the day before his mission trip Krasikov was at a location that required his phones to be turned off completely. On August 17, his phone locked in to his home address for much of the day, and at 17:45 it could be traced approaching Sheremetyevo airport. His last ping from Sheremetyevo airport was at 19:13, just as the Air France airplane to Paris was taking off.

A Russian “Tourist” in Paris

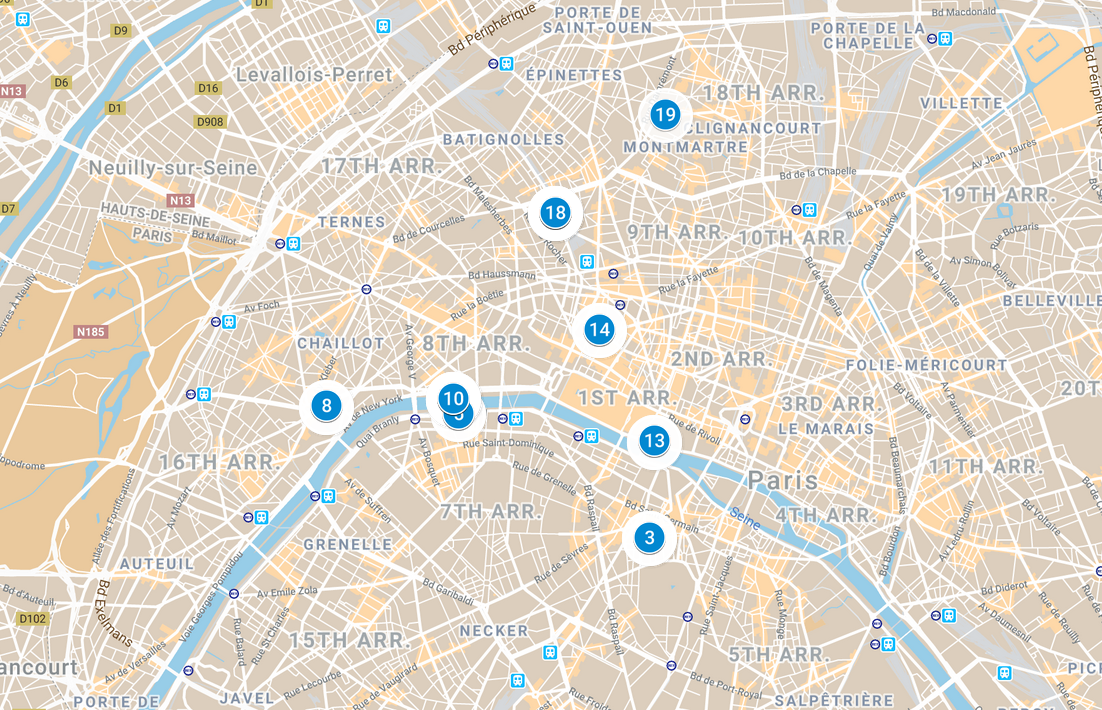

Krasikov’s first two days in Paris are missing from his phone’s connection logs. His first visible connection to a cell tower appears to at 13:15, in downtown Paris, next to Église Saint-Sulpice. This means that either he did not turn on his phone for the initial two days of his Paris stay, or that the data for this period was entirely scrubbed from Russian mobile operators databases.

Places in Paris visited by Krasikov on August 19, 2019

Based on the available cell data, the remainder of August 19 was a veritable exercise in sightseeing. Before going back to his hotel at Charles-de-Gaulle Airport at 5 p.m., Krasikov fully lived his undercover persona of the tourist “Sokolov”, and visited Paris’s most famous landmarks, including the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, Champs-Elysees, the Sacre Coeur Cathedral, Les Invalides and L’église de la Madeleine. This landmark-packed half-day poses an unanswered question as to what Krasikov did — and where he was — between his arrival in Paris on the evening of August 17 and noon on August 19.

On August 20, Krasikov spent the morning at his airport hotel Le Bourget, and last connected to a cell tower in France at the airport at 12:43, just as his flight to Warsaw was departing.

The Famous Palaces Of Warsaw

“Sokolov”‘s phone first connected at Warsaw airport at 3:21 p.m. on August 20. From the airport, he drove straight to his hotel, which he had booked for one week. At 5:30 p.m., he took a taxi to Lazienki Royal Residence park, where he stayed for about 45 minutes in the vicinity of the Lazienki Royal Castle. After that, again by car, he moved on to Warsaw’s Old Town area. He walked back to the hotel at about 8 p.m., and later in the evening walked towards the area of the Sexy Duck restaurant, where he stayed until about half past 10 p.m. before returning to his hotel

The next day around noon he made a few local phone calls which we have been able to trace to a local Russian-speaking tourist guide. It appears that he met the tour guide at his hotel at 3:45 p.m., as he can then be traced riding in a car towards the King Jan III’s Palace at Wilanow. He stayed in the area of the palace until its closing time, and drove back to the hotel around 8 p.m.

On the following day, August 22, the last movement of the phone was registered early in the morning, after which it remained stationary for the next few days, during which it showed periodic GPRS activity, consistent with background synchronization of a phone left unattended. Apparently, Krasikov left his telephone in his hotel room, expecting to return to Warsaw after the Berlin execution, and possibly hoping to use his phone’s location data as an alibi.

Based on the timestamps of the last active use, it can be assumed that Krasikov left the hotel — and made his way to Berlin — just after 8 a.m. on August 22. As there are no airplane records for his flight from Warsaw to Berlin, he must have traveled by car, or more likely, given the location of his hotel near the central Warsaw train station, by train. A train ride would have gotten him to Berlin that Thursday afternoon.

He shot Zelikhman Khangoshvili twice in the head with his modified Glock 26 pistol the next day at 11:58 a.m.

Status Of Investigation

A Government-Sanctioned Operation

Based on our findings, the hypothesis that Khangoshvili’s murder was a criminally motivated gang-style execution can be conclusively eliminated. Similarly, the operation cannot be linked to retribution from Chechnya’s ruler Ramzan Kadyrov, as none of the people Krasikov communicated with in the run-up to the operation can be traced to Chechnya’s security apparatus, which is competitive and oftentimes hostile to the FSB.

A scenario in which the execution was planned as a private vendetta by former Spetsnaz officers who had personal revenge motive is also improbable. Krasikov’s systemic interaction with the FSB, including training at the security service’s most secure locations where each visit is subject to express access approval and logged, cannot plausibly be explained by private initiative from rogue FSB officers.

Equally implausible would be the ability of a private operation within the FSB to ensure the paper creation of a complete new fake persona, with all requisite registrations in all government databases, such as tax and residential registries. The comprehensive purging of these same registries following Krasikov’s arrest, the manipulation of cell-phone metadata, and Russia’s insistence in communication with German authorities that Krasikov is in fact “Sokolov”, can all be explained only by a government operation planned and sanctioned at a central level. Russian president earlier disclaimed any direct involvement in the murder, attributing the killing to an undefined “criminal milieu“. Officially, Russian authorities continue to allege to German prosecutors that Vadim Sokolov is an existing person traveling under his real name and with valid documents.

A question without a definitive answer as yet is whether this operation was solely planned by FSB. While the direct evidence points to the FSB’s crucial role, certain clues – such as the issuance of Krasikov’s fake employment documents by a company that can be linked to the Ministry of Defense, and his interactions with at least one former GRU Spetnaz officer, imply that operation may have received intra-agency support from the GRU. Vympel (now Department “V”) and GRU have a long history of collaboration, both during Soviet time and in the two Chechen wars.

Contract Killer Or Spetsnaz Officer

Based on our latest findings, our earlier uncertainty whether Krasikov is a (former) Spetsnaz officer, or simply a contract killer who was co-opted by the security services for this operation, appears to be resolved in favor of the former. It is implausible that an assassin with a criminal background of at least two known contract murders would be permitted regular access to FSB’s CSO and the service’s most secure locations. Equally unlikely is that such a person would have a circle of contacts almost exclusively from among current or former Vympel members (or a former GRU Spetsnaz member, as in the case of one of Krasikov’s contacts).

Other details from Krasikov’s biography also contribute to the (former) Spetsnaz hypothesis. As we wrote earlier, our review of various archived databases show that his first passport appears issued at age 27, with no information about the history of prior ID documents. This would be consistent with using a military ID prior to the first passport, although other explanations for this discrepancy are also possible.

A significant clue that Krasikov may have been a decorated former Spetsnaz officer comes from a trip to Kyrgyzstan he took in 2011. Flight records show that he made the three-day trip to the former Soviet country’s capital Bishkek together with Vladimir Fomenko, a highly decorated FSB officer. Krasikov and Fomenko flew to Bishkek on November 30, 2011 and returned on December 2, 2011. Court documents related to the 2007 murder of a Karelian businessman — in which both Krasikov and Fomenko were indicted before their case was suddenly dropped — show that Fomenko had received a special government award from the President of Kyrgyzstan, a Glock 10 pistol. The November 2011 trip was the only time Fomenko visited Kyrgyzstan under this name, and it is therefore likely that was the trip during which he received the award. December 1, 2011 was the last day in office of outgoing president Roza Otunbaeva, which would be consistent with a period for bestowing state awards. In this hypothesis Krasikov either traveled with Fomenko to keep him company, which is rather unlikely, or to receive an award of his own. Through The Insider, we have posed a question in this respect to the former president of Kyrgyzstan but have received no response at press time.

How We Investigated

Initially we needed to find out which telephone numbers were used by the suspect. A check with sources at the Russia’s four major mobile operators in Russia showed that he does not have a contract with any of them under his real name Vadim Krasikov. We did discover, however, that there was a phone issued to his cover persona of “Vadim Sokolov”. However the sim card for this number was issued only in mid-August, and while it would provide useful data for the days following his departure to Berlin, it would not shed any light on his movements and interactions during the preparation for the execution.

GetContact number entry for “Eduard Vitalyevich”, the name and patronymic for Benderski. We reached him via this number