Identifying The Berlin Bicycle Assassin: Russia's Murder Franchise (Part 2)

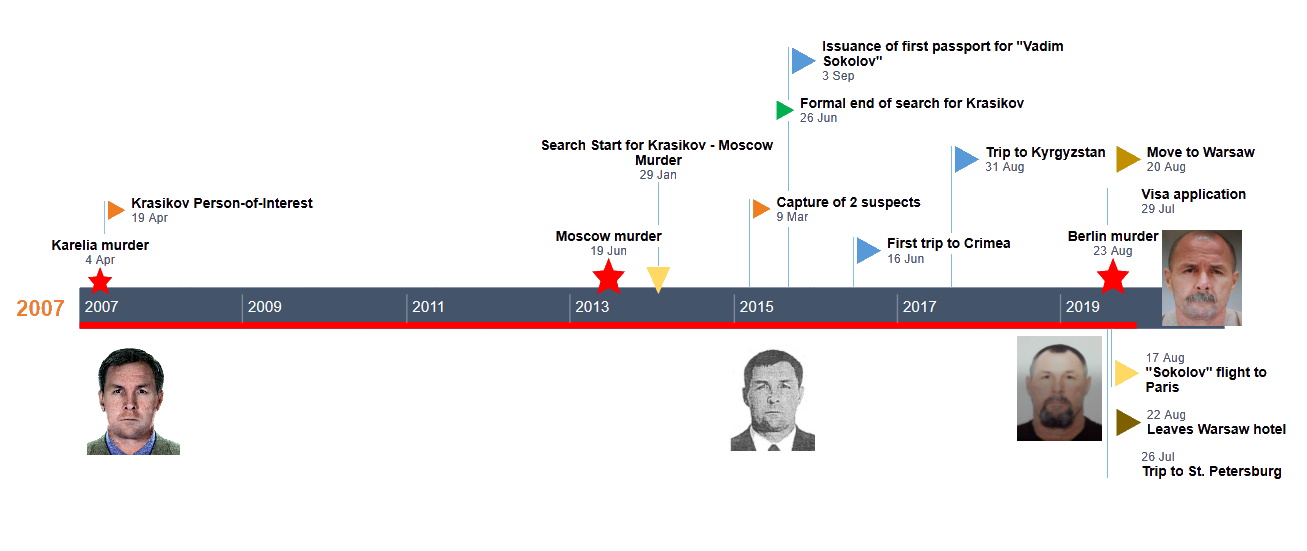

- In the previous part of this investigation, we identified the assassin of Zelimkhan Khangoshvili as Vadim Nikolaevich Krasikov, a 54-year old Russian citizen traveling with state-issued false identity papers. Khankoshvilli, an ethnically Chechen Georgian citizen who had fought against Russia in the Second Chechen War and was linked to Georgian military intelligence, was shot and killed at close range by a cyclist in broad daylight at a park near Berlin’s Kleiner Tiergarten. We disclosed that the detained suspect had been a key suspect in a previous murder in Moscow in June 2013, where the killer had also used a bicycle to approach his victim and escape.

- We also disclosed that Russia had terminated both domestic and international search warrants issued for Vadim Krasikov just over a year after their issuance, in mid 2015. This lifting of the warrants occurred only a couple of months before Krasikov’s fake identity papers were issued under the new, cover name of “Vadim Sokolov”.

- Following our publication, Germany’s Federal Prosecutor announced that it is escalating the investigation to a federal level, based on its assessment that the murder was likely commissioned by representatives of the Russian state. In its public statement, the Federal prosecutor’s office confirmed the key findings presented in our previous reports., including the true identity of the suspect and the evidence for the Russian state’s involvement.

In this part of the investigation we present newly discovered evidence that at the time Russian authorities detained Vadim Krasikov – presumably around the time his search warrants were revoked in 2015 – he was wanted for a second, previously unresolved murder in Karelia. A recidivist murder charge would have resulted in a severe jail sentence, in all likelihood a life jail term. This circumstance would have aggravated his personal prospects, and, coupled with his track record as a hitman, would have made him a suitable target for recruitment by Russia’s security services.

Crucially, we report evidence that as early as in 2007, Vadim Krasikov had close links to Russian security services and is likely to have been a member of one of FSB’s spetznaz units, the elite team known as “Vympel”.

***

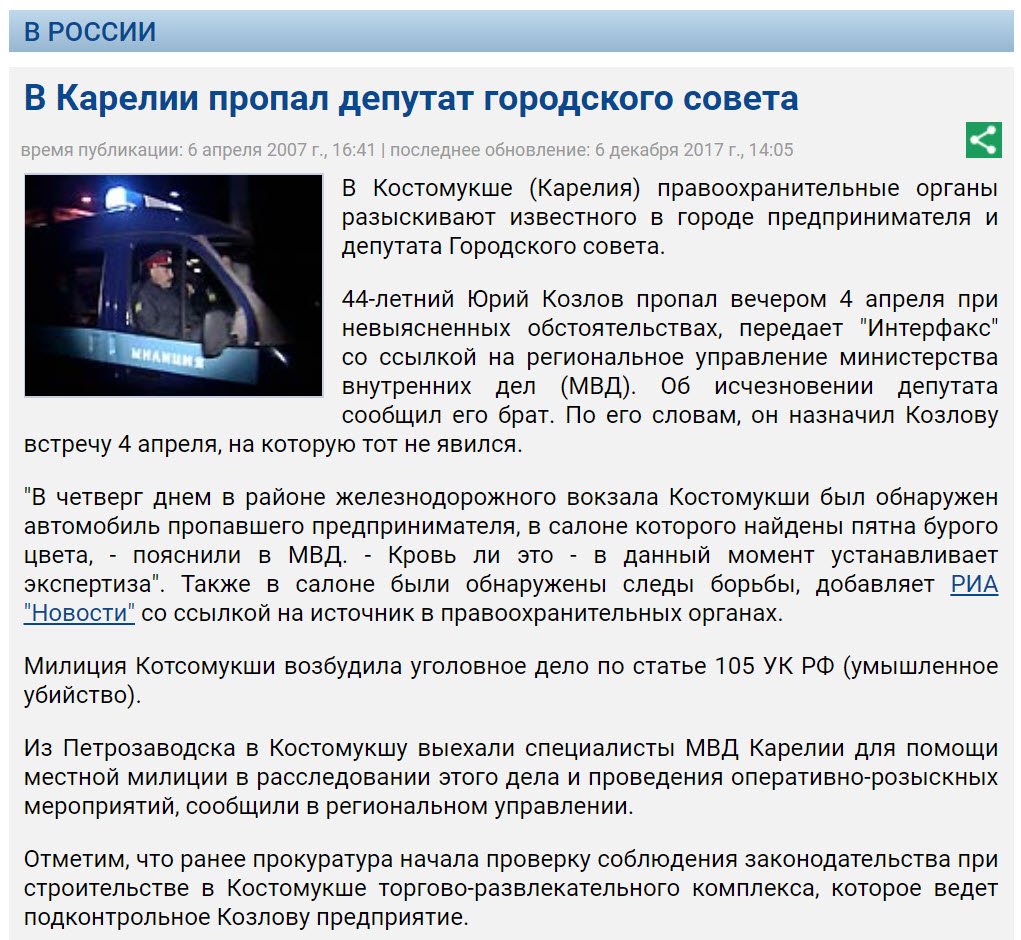

At 11pm on 4 April 2007, Yury Kozlov, a member of the city council in a small town in the northwestern corner of Russia, was not home when his brother came to see him. Yury Kozlov’s phone was switched off and his car was missing, and at the place where his car was usually parked, his brother Alexander could see dark damp spots that appeared like they might be blood stains. Alexander got worried when his brother failed to show up after midnight, and called the police.

Article from NewsRU regarding the disappearance of Yury Kozlov, from 2007

After an overnight search operation in the sleepy town of Kostomuksha in Russia’s Republic of Karelia, Yury’s car was found near the train station the next morning. It had been left deserted, and there were signs of fighting and blood on the car floor, as well as traces on the ground from a body being dragged. Witnesses living nearby claimed to have heard two shots that followed a noisy scuffle.

The search continued for the next few days, weeks and months, but to no avail, until on 23 July, mushroom-pickers found a decomposed body in the Karelian forest, about fifteen kilometers from the location of the car. Kozlov’s relatives were able to identify the body as belonging to Yury, age 44. Police reported that he had been killed with several pistol shots into his body.

Theories about the motive for the murder ranged from business strife between Kozlov and another local entrepreneur – both were building rival shopping malls in a town that hardly had a population for one – to a family feud with another local clan. No suspects in the murder were publicly announced, and the investigation slowly turned into a cold case.

But behind the public view, local investigators had been working on leads even before the remains of the body had been found.

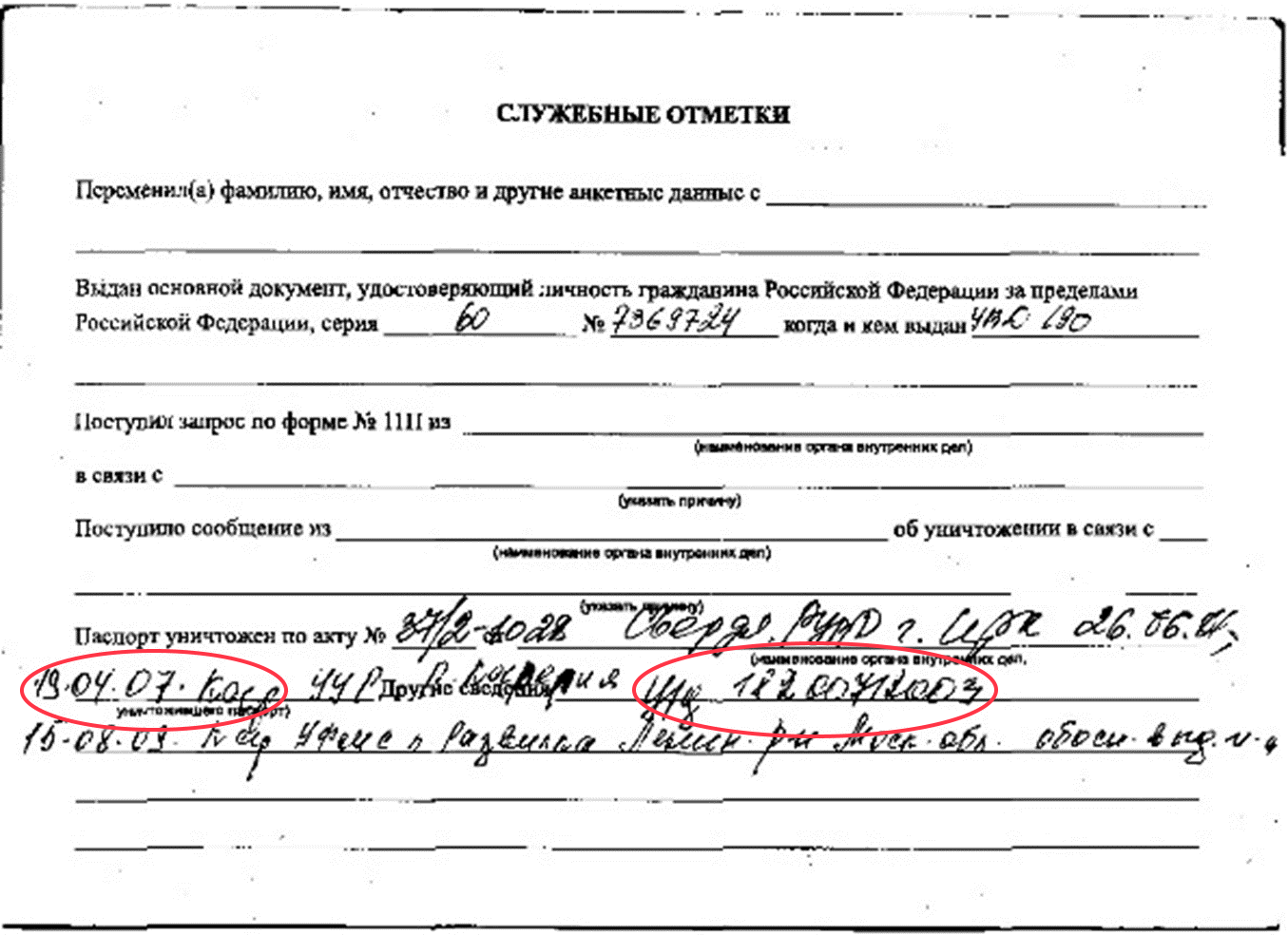

A form contained in Krasikov’s passport dossier showing markings requesting his file in connection with a 2007 criminal case

A review of hand-written notes on one form from Vadim Krasikov’s passport file, seen above, shows that on 19 April 2007 – two weeks after the entrepreneur had vanished- the local Karelian investigative office had requested a copy of Krasikov’s passport file. The marks on the form also reference a criminal case number in connection with which information was being sought: №18200712003.

We tried to obtain, via a whistle-blower with access to the local Karelian police database, a case file on Vadim Kasikov (the so-called IBD-R dossier that aggregates all information on suspects or victims in a given region). There was no file on Krasikov in the Karelian police records.

However, the same source was able to pull up data on the case file 18200712003: indeed, this was a criminal case launched on 5 April 2007 in connection with the disappearance of Yury Kozlov, the Kostomuksha entrepreneur. The criminal case was initiated pursuant to article 105 of Russia’s criminal code, which means that even before finding the dead body, the investigators were presuming Kozlov had been murdered.

The fact that the police had a suspect so early in the investigation had never been publicized. The missing local IBD-R record on Krasikov makes it impossible to study why investigators thought Krasikov a person of interest in the case. For the next few years, no further public information about the process of the investigation was made public.

***

Eight years later, on 10 April 2015, a local news website brought news of the cold case being revived. The site reported that the investigation had been resumed when, “a short time ago”, police had detained two persons in Moscow who had reportedly made confessions to the murder, and had even been brought to Kostomuksha in the process of the investigation. The website also reported that searches were being held at the offices of an influential local family who had run the rival shopping mall project in 2007.

While it was impossible, given that Krasikov’s police file was purged, to find hard evidence that he was directly linked to the 2007 murder, a number of circumstances clearly pointed us to that conclusion.

First, it was known from Krasikov’s passport file that he was a person of interest in the case. Second, there is no file for Krasikov in the local IBD-R Karelia record. This absence is abnormal in the event he was a person of interest, which is established from the markings on his passport form. What was even more unusual, however, was that in the victim’s own local police file – Yury Kozlov’s IBD-R dossier – there exists no data relating to his disappearance and murder. In other words, both local police files in Karelia that would have had a reference to the local 2007 murder – just like Krasikov’s own national police dossier – had been thoroughly, and apparently manually, purged. Thirdly, several months after the detention and alleged confession in Moscow (which would have taken place in late 2014 or early 2015), Krasikov’s national and international search warrants were taken down.

We concluded that Krasikov was either one of the two captured suspects, or a third accomplice that the two suspects pointed to after their arrest in Moscow.

The Untouchables from Vympel

Faced with purged records of any of the crimes and associated court cases (no reference to the criminal case mentioned in Krasikov’s passport file exists in the Karelian court system), we approached Alexander Kozlov, Yury Kozlov’s brother. He confirmed to us that shortly after his brother’s murder, investigators had focused on three suspects who – hotel records showed – had arrived and stayed in the town hotel in Kostomuksha the evening his brother vanished. One of the suspects was indeed Vadim Krasikov.

Alexander told us that on 20 November 2014, police detained the other two suspects: Oleg Ivanov (born 23 July 1976) and Vladimir Fomenko (born 23 June 1976). Police were already searching for Krasikov on an arrest warrant in connection with the 2013 Moscow bicycle murder. At some point in 2014 or early 2015, Krasikov was also detained. All three of them were brought by investigators to Kostomuksha, and they all admitted to having been in town on the night of the murder, but claimed that had nothing to do with the crime itself – arguing that they flew in and out as tourists.

Alexander tells us that only Ivanov and Fomenko were formally charged with the murder, and were brought before court in Karelia’s capital Petrozavodsk (Alexander himself attended the court hearings). Krasikov was never brought to court, and Alexander Kozlov never understood why.

In arguing for their release on bail, the defense told the court that they could not have committed the gruesome murder, as they were highly decorated veterans of FSB’s Vympel spetsnaz team. Several other veterans from the elite Vympel unit came to offer the court character testimony, and even offered bond payments to ensure their comrades would be let out on bail.

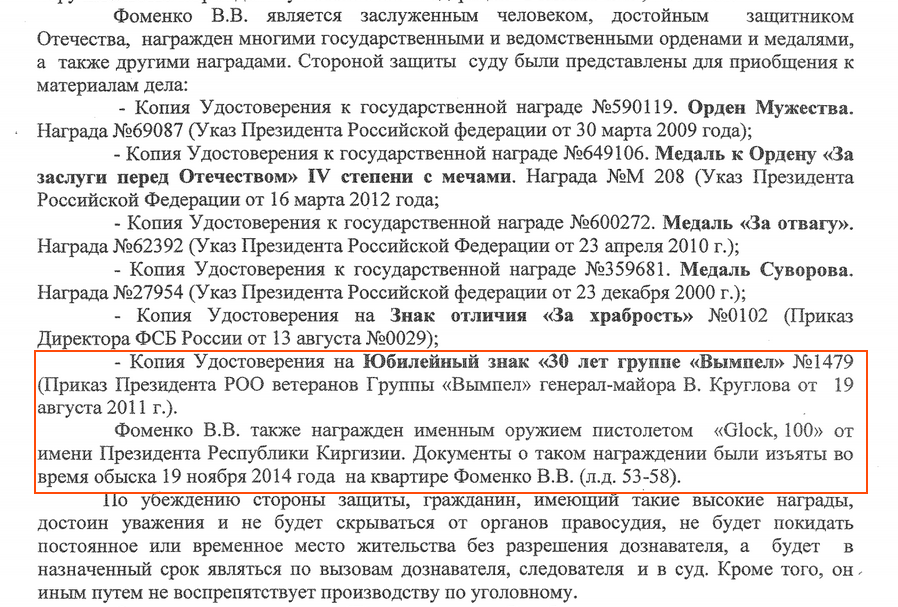

Even the court decision to extend their imprisonment, which Alexander shared with us, refers to their legacy at the elite special operations group in its decision to acquit:

“Fomenko is an honorable defender of the fatherland, decorated with multiple state orders, including the Courage Order, the Services to the Fatherland Medal, the Suvorov Medal…..and also a named Glock-100 pistol awarded personally by the President of Kyrgyzstan”

Extract from a court decision from Petrozavodsk’s court, listing the awards bestowed to Fomenko – including a Glock-100 from Kyrgyzstan’s president.

In 2015, Alexander was told that the case has been taken up by the Directorate for investigation of extraordinarily important cases of Russia’s central investigative committee, or SledCom. He was later told that the case had been dropped due to insufficient evidence against the suspects and no further new leads. We have reviewed letters sent from SledCom to Alexander Kozlov that confirm his statements.

Alexander Kozlov appears to have no doubts that all three suspects – including Krasikov – shared a common past in Russia’s elite FSB unit. Court documents show that Alexander wrote to the court stating he fears for his life, given that the third suspect – Vadim Krasikov – was still at large. While there is no paper-trail of his work for the spetsnaz group, there is also no record of any gainful employment he had pursued. Krasikov’s former wife, approached by our partner Der Spiegel, said she did not know what his job had been while they were married, as it was “some business women are usually not informed about”. We also found flight booking record showing that Krasikov flew to Kyrgyzstan – the place where at least one of the other accomplices in the Karelia murder had earned a high award- on two occasions, once in 2011 and a second time in 2017.

Alexander Kozlov tells us that having seen coverage of Krasikov’s arrest in Berlin, he plans to write to the SledCom chief and insist on a re-opening of the cold case, now that it is clear that Krasikov is indeed a murderer.

The Petrozavodsk court system does not yield any results under either the case number of the criminal case Alexander personally attended, nor under any of the names of the charged – and acquitted – suspects.

Catch and Release

The most plausible hypothesis of what happened in 2015 was that Krasikov – who was already wanted under the 2013 murder arrest warrant – was detained at some point in 2014 and was forced to confess not only to the Moscow 2013 murder but also the Karelia 2007 murder. This, in turn, likely led to the arrest of the other two accomplices in the Karelia murder.

In this scenario, Krasikov would have known that he was facing prospects of a lifetime in prison. This would have made him highly susceptible to recruitment as a hitman for Russia’s security’s services, especially under Alexander Kozlov’s hypothesis of his elite spetsnaz background. Russian security services are known to have used criminals – some with FSB or police background – in similar predicaments for extraterritorial assassinations in at least two other cases we have researched (see Public Private Partnerships, below).

***

Following the capture of Vadim Krasikov and the release subject to whatever arrangement he achieved, there is a blank period until the end of 2015 where he does not pop up in any data sources we have reviewed. However, three months later, on 3 September 2015, the first trace of another persona – Vadim Sokolov, born 20 August 1970 – appears in the Russian legal universe. That is when the first domestic passport (a rough equivalent to an European ID card) was issued to “Sokolov”, the fake persona who at that moment would have been 45.

Living a parallel life to his new persona as “Sokolov”, Vadim Krasikov continued his own life, out of prison and ostensibly out of trouble with the law. The annual tax report for Vadim Krasikov for 2015 shows that he earned 140,000 rubles (approx EUR 2,000) from employment at a company named ORD Ltd. Later years’ tax filings show that he continued to be “employed” by this firm through 28 February 2018. A review of the Russian companies register shows that there are three companies with that exact name. When approached by us, none of the three said they employed, or knew of a Vadim Krasikov. If that is true, Krasikov’s employment status was entered into the tax database without grounds – something that, like many other things in this case, would have required an intervention from a state actor.

Krasikov did not travel commercially for the 14 months following his presumed detention (the travel databases consulted by us for this research capture all commercial forms of travel but not personal auto travel). He resumed air-travel in July 2016, when he flew to Simferopol (Crimea) on 17 July and stayed until 1 August 2016. A year later, on 31 August 2017, he flew from Moscow to Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan. He stayed there five days and returned to Moscow on 4 September 2017. In the next year, he flew from Moscow to Crimea a total of four times, each time staying between 5 and 7 days, with the last trip returning him to Moscow on 12 July 2018. We have not yet been able to correlate his travel dates to significant events in either Kyrgyzstan or Crimea during the times of Krasikov’s trips. However, shortly after the annexation of Crimea, Krasikov’s two 2007 partners in crime established a private security company in Crimea, and his trips may have been related to that enterprise.

On 26 July 2019, Vadim Krasikov made a one-day return trip from Moscow to St. Petersburg. This was a Friday; on the following Monday, Krasikov would appear at the French consulate in Moscow, carrying documents – including fake employment papers issued by the St. Petersburg company RUST – that would misrepresent him as St. Petersburg resident Vadim Sokolov, an engineer earning 80,000 Rubles (EUR 1,100) a month who wanted to see Paris. The French consulate would naively buy into this fiction and issue him a visa the next day.

Purge, Rinse, Repeat

Bellingcat already reported that many previously existing records of Vadim Krasikov have vanished from Russian registries at some point in the last months or years, while others have been falsified. These include records of his driver’s license, criminal records (both national and local), and residential records.

We have since also discovered that records relating to Krasikov’s second wife have also been purged from registries. While offline data sources show that Krasikov married his second spouse in Moscow in 2010, there are no records of such marriage in the current version of Moscow ZAGS (family status database). Records of two cars owned by his wife from offline sources downloaded as recently as 2018 currently cannot be seen by sources with access to the traffic-police database. Similarly, residential records from the two addresses where his spouse has been listed as registered in the last five years show no entry for Krasikov’s wife, including in historical checks.

Public-private partnerships

The use of criminals as proxy assassins by Russia’s security services is not without precedent. In April 2019, a car bomb exploded prematurely as it was being placed under the car of an officer from Ukraine’s military intelligence at his home in Kyiv. The Ukrainian military intelligence officer had played a crucial role in incapacitating Russian military activities in one critical military confrontation in the Donbas a few years earlier.

The person who was placing the car – and who lost his limbs in the explosion but despite severe blood loss, was saved by Ukrainian medics – had traveled to Ukraine under a fake identity.

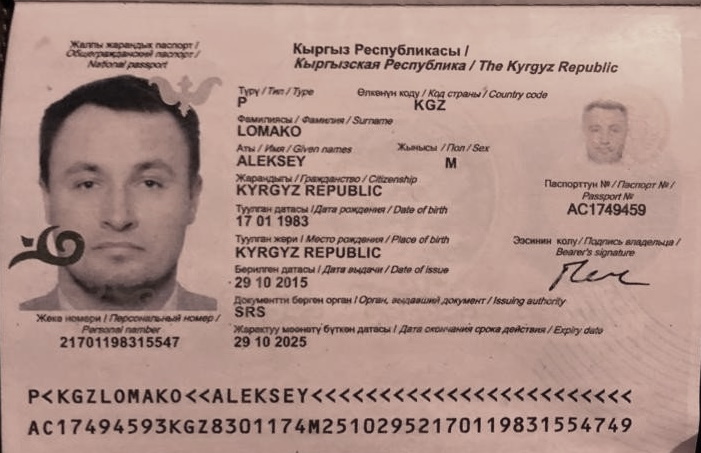

The would-be assassin traveled under the fake identity of Aleksey Lomako, a non-existing Kyrgyz citizen born in 1983. In fact, back then Bellingcat identified him as Alexey Komarichev, a Russian citizen born five years earlier, in 1978 (coincidentally, Krasikov’s fake alter ego is also five years younger).

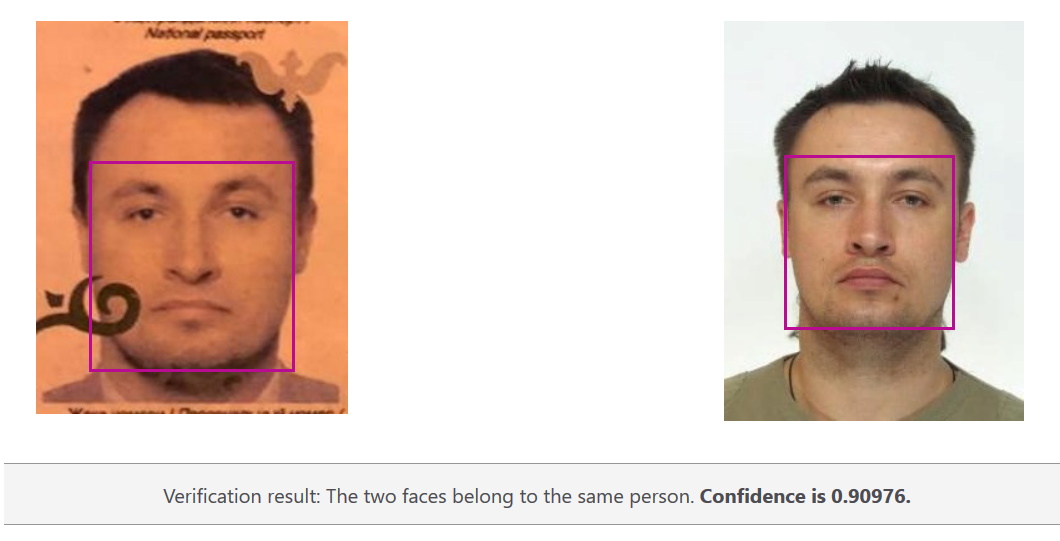

Fake Kyrgyz passport used by Russian hired operative Alexey Komarichev to travel to Ukraine in April 2019

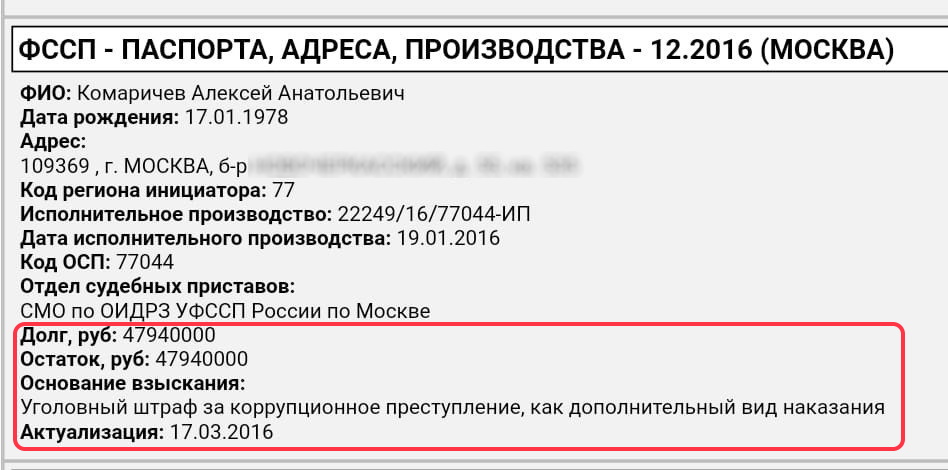

Facial comparison between “Lomako” and Komarichev using Microsoft Azure Face API confirms both are the same person. In analyzing open source data and leaked Russian databases, we then identified the most plausible reason for this operative’s acceptance of, what turned out almost literally, a suicide mission. While a former police officer investigating drug crimes in Moscow, Alexey Komarichev had been caught accepting a bribe. This resulted in a criminal charge that – in addition to a prison sentence – required him to pay a criminal fine of nearly 48 million rubles (approximately EUR 700,000). The hefty fine plus the prison term are likely to have appeared as a less attractive option to accepting a risky mission abroad, in return for absolution.

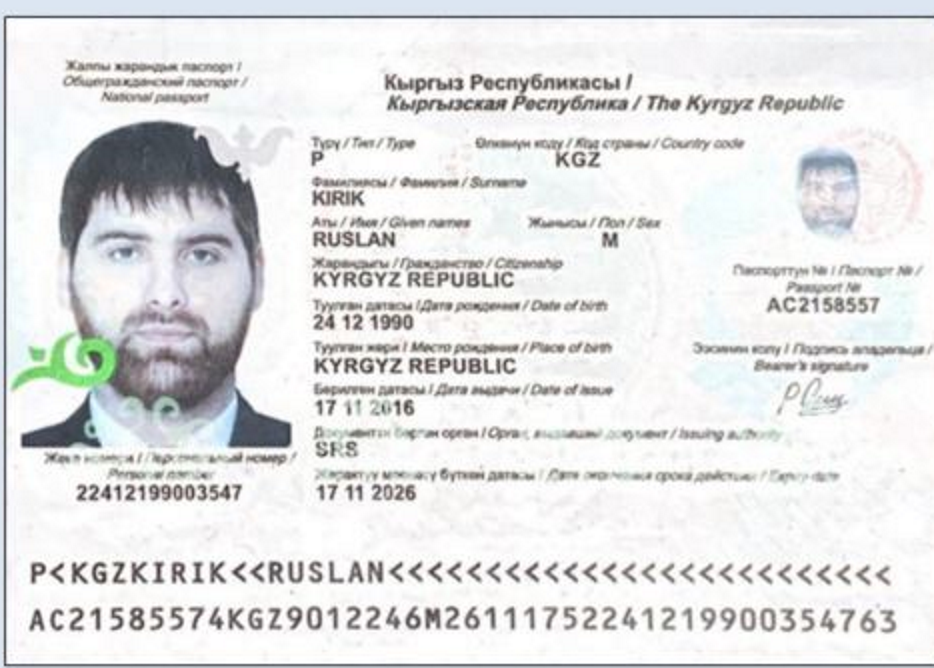

While at the time of the explosion there was no information to help decide which of Russia’s security services would have recruited Komarichev, an arrest of another Russian operative in Kyiv a few days later provided the answer. The contents of Komarichev’s mobile phone contained reference to another person with a Kyrgyzstan passport, which Ukrainian authorities found out to be still in the country. A reverse face search in open source data led to the real identity of the accomplice: Timur Dzortov, a former Spetznaz officer in Ingushetia. He was detained in Kyiv and confessed that he and Alexey had been recruited by the GRU in 2017, underwent additional weapons, sabotage and bomb-making training in Moscow, Rostov and Donetsk, and were deployed to Kyiv with the express mission to assassinate a Ukrainian military counter-intelligence officer. Previous unsuccessful attempts, by Dzortov’s confession, included a knife attack that was planned to appear as random street crime, and murder by firearms. When they found out that the target could not be easily approached within striking distance, the instruction from their GRU handler in Moscow was changed towards placing an IED under the target’s car.

Fake Kyrgyzstan passport issued by GRU to Timur Dzortov.

At the time of Dzortov’s arrest in Kyiv, all data about his existence had been deleted from Russian state-run databases. Both Dzortov and Komarichev are still in Ukrainian custody.

Important: Russia has deleted all records of the existence of Timur Dzortov from RU databases. No such person in the central passport database (anymore). No such person with tax ID or driving license (anymore).

Yet, he existed in Sept 2018, as he is in our offline databases:)— Christo Grozev (@christogrozev) April 17, 2019

In a recent investigation, the New York Times disclosed another case of Russia’s security services using ex-convicts to liquidate targets were believed to have spited Russia years earlier. In 2015, after being wounded in fighting in the Donbas, a Russian citizen with a hefty prison record was recruited by Russian security officers in Moscow after he tried unsuccessfully to join the Wagner PMC to go and fight in Syria. A year later he found himself in the Western Ukrainian town of Rivne, where he profiled, tracked, shot and killed an unsuspecting Ukrainian prison guard. The killer had received a list of six targets, and had been trained in the basics of trade-craft, using floral code-words to decipher instructions he would receive as text messages from Moscow. After he killed the first target, he flew back Moscow to claim his award and prepare for his next assignment, but was captured during a cursory trip to Ukraine to surprise his Ukrainian girlfriend on her birthday. Having found about the murder, she tipped off Ukrainian police.

An analysis of the six targets that were on the laymen assassin’s list showed that they shared only one thing in common: all of them had assisted, in roles of military advisers or volunteers, Georgia’s army during its 2008 war with Russia.

These two recent state-commissioned assassination attempts bear certain common features with the Berlin murder, and may produce clues as to the most likely motive behind it. In both cases Russian security services used ex-criminals, supervised by actual staff officers, to try and create a layer of deniability. And in both cases the motive was not national security concern or operational necessity. Rather, the motive appeared to be revenge for prior actions by the targets that had been seen as hostile to Russia, in one case during the war in eastern Ukraine, and in the other during the Georgian-Russian war. This may well have been the motive in the case of Khangoshvili, who took active part in the second Chechen war, but was also involved in the Georgian-Russian war when he reportedly acted in service of Georgia’s military intelligence.