GRU Globetrotters 2: The Spies Who Loved Switzerland

In the first part of this “GRU Globetrotters” series, Bellingcat and its investigative partner The Insider teamed up with BBC Newsnight to trace the London movements and potential role of Russian GRU officer Denis Sergeev during the time that the Skripals were poisoned in Salisbury. The research was made possible thanks to telephone metadata which Bellingcat obtained from a whistle-blower previously working for the mobile phone operator to whose services Sergeev’s fake alter ego “Sergey Fedotov” subscribed.

In this second installment, we teamed up with Swiss media group Tamedia to trace Sergeev’s multiple trips to Switzerland in the period of 2014 to 2018, with a focus on his 2016-2018 trips for which we have obtained telephone metadata.

- Bellingcat initially identified “Sergey Fedotov” as Denis Vyacheslavovich Sergeev, a senior GRU officer who had been decorated for being wounded in military action in the Caucasus where he served as a Spetsnaz field commander.

- In a follow-up publication, we reported that in 2015 he and a team of other undercover GRU officers flew under fake identities to Bulgaria during the days when a Bulgarian arms exporter fell into a coma in yet-unexplained circumstances. Following that publication, Bulgarian authorities announced that they have reopened the 2015 cold case, and confirmed that “Sergey Fedotov” was a person of interest.

- In the previous part of this investigation, we researched Sergeev/”Fedotov”’s data and voice communication during his London trip and concluded that he likely played a supervising and coordinating role in the clandestine operation of GRU officers Col. Chepiga and Col. Mishkin in Salisbury. Our reporting partner BBC also cited its own sources who disclosed that Sergeev has a rank of major general.

- In preparing the current report we reconstructed, often on a minute-by-minute basis, Sergeev’s multiple trips to Switzerland, the last of which was just over a month before his London trip at the time of the Novichok poisonings. Thanks to access to unprecedented granular data, we and our investigative partners, Tamedia and The Insider Russia, analyzed the GRU spy’s movements over a total of 39 days in the period of 29 September 2017 to 17 January 2018. For contextual understanding and to arrive at hypotheses for his missions’ purpose, our investigative partners assisted with information from police, judicial, and intelligence sources in several countries.

The exact reasons for Dennis Sergeev’s repeated clandestine trips to Switzerland remain unknown to us and our investigative partners. The analysis of his movements, however, allows us to formulate certain hypotheses. Through carelessness or overconfidence, Sergeev always used the same mobile device, and remained continuously connected to the mobile data network. During his travels in Switzerland, he connected a total of 12,708 times to various cell tower antennas, leaving a trace of digital crumbs we and our investigative partners meticulously followed. He also made 108 calls to a single number with odd characteristics: a “blank” number with no registered owner and no digital footprint. This was the same number with which Sergeev exclusively spoke 11 times during his trip to London in March 2018, including just before the Skripals were poisoned. In our previous report, we tentatively named Sergeev’s exclusive interlocutor “Amir from Moscow”, owing to the name that shows up against this number in GetContact, a phone contact sharing app popular in Russia.

Trip 1: 5 to 11 November 2016

Barcelona-Zurich

At the start of November 2016, Sergeev took his first trip to Switzerland, arriving initially to Barcelona and leaving via Zurich a week later, as evidenced by airline data previously obtained and reported by Bellingcat and our investigative partners. Unfortunately, in 2016, he did not yet indulge in full-time internet usage while in roaming, which prevents us from accessing details of his movements during his first trip. However, several text messages received by him on the day after his arrival to Barcelona contain cell-tower metadata. These few data-points show that he traveled from Barcelona to Switzerland on November 6, the day after arriving – a “detour” or “decoy” pattern that we will see repeated a year later.

Possibly coincidentally, shortly after this trip, the computer of a senior FIFA anti-doping official based in Zurich was compromised by GRU hackers. As reported in Mueller’s indictment in case 18-263, as of 6 December 2017, more than 100 sensitive documents were downloaded from his hacked computer, including internal papers on FIFA’s anti-doping strategy, laboratory results, medical reports, contracts with doctors and testing laboratories, information on medical procedures, and anti-doping tests. As we have reported earlier, Col. Mishkin and Col. Chepiga – whom we now know to be subordinates of Dennis Sergeev – were in Switzerland at that very time and departed Geneva on 7 December 2017. Furthermore, as reported in Mueller’s indictment shortly before his trip, in September 2016, another pair of GRU hackers, Evgeniy Serebryakov and Aleksei Morenetz, travelled to Lausanne to attempt on-site hacking of WADA’s servers. While it is not possible to firmly link Sergeev’s 2016 visit to these hacking attempts, his senior rank and his subsequent focused visits to WADA’s European headquarters imply he may have had a coordinating or other role for that GRU operation. Notably, the hacker teams subsequently arrested in the Netherlands in 2018 also consisted of a combination of computer experts and traditional espionage operatives.

Trip 2: 29 September to 9 October 2017

Barcelona-Geneva-Lausanne

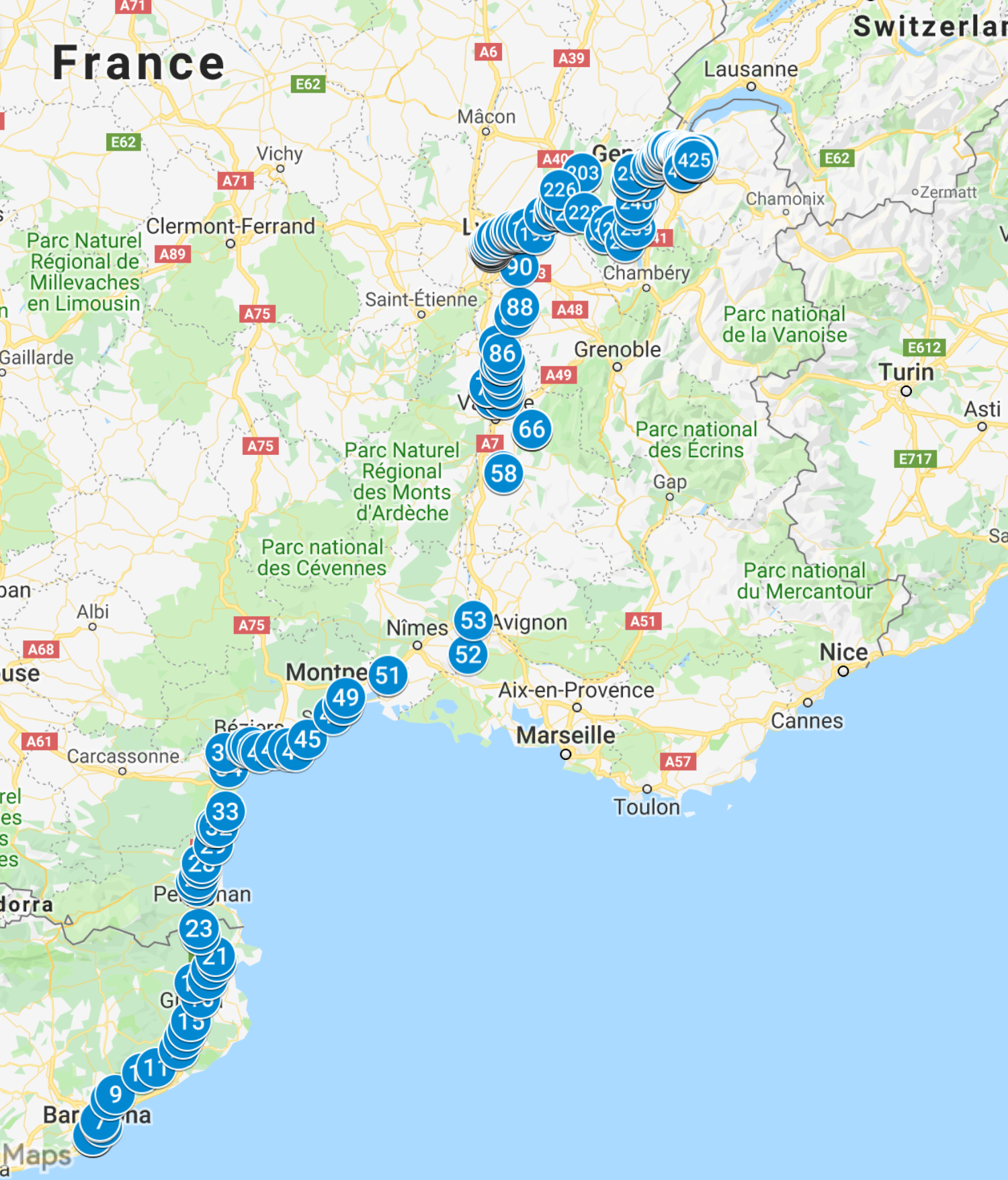

At the end of September 2017, Sergeev traveled to Switzerland again for about ten days. Similarly to a year before, he again flew from Moscow to Barcelona on Aeroflot flight SU 2638, this time just days before the Catalonia independence referendum. He stayed in Barcelona overnight on September 29, and after lingering near the central beach area for about an hour, he made his way to Geneva. Comparing the pattern and timing of his movement during the day and the fact that he stopped in Lyon around noon, we established that he travelled by train, changing trains in Lyons. His connections to the Geneva railway station cell towers coincides with the arrival time of the train from Lyon that day, near 16:40.

Sequential numbers show the movement of Dennis Sergeev’s phone on 30 September 2017 from Barcelona to Lyons and then on to Geneva

It is not exactly clear why in both these trips, Sergeev traveled first to Barcelona. He may have had brief meetings with contacts there, and may have wanted to combine trips; or it could be that he could not obtain a Swiss visa and instead had a Spanish visa. While both countries are in the Schengen area, a Russian person arriving to Switzerland on a non-Swiss visa is usually subjected to more questioning about the purpose of entry, and he may have wanted to avoid this scrutiny. His phone records prior to both trips show that he frantically called travel agencies and visa-support services, which may be an indication that indeed he could not obtain a Swiss visa and had to “settle” for a Spanish one.

Whatever the reason for the long detour, having arrived in Geneva on 30 September 2017, cell tower traces left by Sergeev’s phone indicate that he took tram 12 towards neighbouring France and crossed the Franco-Swiss border at Thônex. The hotel Appart’City, in Gaillard, where we later find data evidence he likes to stay at, is less than a three-minute walk from the border post.

The apart-hotel’s seven-story building, badly worn out, is not really a dream resort. But at rates starting at 67 francs per night, and with good public transport connections to the center of Geneva, the hotel’s value for money is hard to beat.

The exterior of Apart’City Hotel on the French side of the Swiss-French border, where Sergeev repeatedly stayed during his trips. Credit: Sylvain Besson

In the following days, Dennis Sergeev obviously had only one target: Lausanne. But unlike his subordinates a few months later, he was not interested in the famous Lausanne cathedral. On Monday, October 2, he went to Thonon by car, then boarded a passenger boat to Lausanne, where he arrived around 11:30 am. He left Lausanne also by boat an hour and a half later: this gave just enough time to make a round trip to Ecublens, near the EPFL, the Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, one of the most renowned science and technology institutions in Europe and the home of over 350 on-campus laboratories.

Two days later, on Wednesday, October 4, he returned to Lausanne by car and stayed about four hours in the area between Vidy, Ouchy and the south of the train station, where most of the international sports organizations in the city are located. At that time, the Court of Arbitration for Sport was just about to decide the fate of Russian Anna Chicherova, an Olympic high-jump medalist accused of doping. Crucially, Sergeev’s telephone also connected to the cell antenna inside the Maison du Sport, where the Lausanne office of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) is located.

Finally, on Friday, October 6, Dennis Sergeev came to Lausanne for about ten hours: he exited the highway into town at Ecublens at 8:14 in the morning and left back by the same route at 18:06. The data from his phone places him this time on the EPFL campus.

By a curious coincidence, the American ambassador to Switzerland, Suzan LeVine, who left her position a few months earlier, gave a public lecture that afternoon at the Rolex Learning Center, and stayed for a while longer to give awards to students. At this precise moment, Sergeev’s phone connected several times to the Rolex building’s indoor antenna. As testing conducted by investigative partner on the spot proved, it is only possible to connect to this cell tower antenna inside the virtual Faraday cage of this concrete building.

We have not been able to establish the reason for Sergeev’s interest in staying proximity to the former U.S. ambassador. Was he keeping an eye on Suzan LeVine and her husband while another team tried to introduce a virus or hack into a laptop computer left at the Palace Beau-Rivage where the couple had left their luggage? No longer in office, the diplomat was not entitled to any special security, so perhaps this was seen as a low-hanging opportunity by a GRU team that was already in town. Targeting foreign former government officials – who may or may not come back into positions of political relevance under a future administration – appears to be compatible with the long-term strategy of an intelligence service.

When contacted by our team and informed of the presence of a GRU officer at the event she spoke at, Suzan LeVine was perplexed: “I have no idea what he may have wanted,” she told us.

Many questions about Sergeev’s multiple visits to Lausanne remain unanswered: Were there any other officers with him? Did they again attempt to hack into World Anti-Doping Agency computers, as other GRU members had already attempted on 19 September 2016? As reported in the U.S. indictment, it was on that day, during a WADA-organized anti-doping conference at the Alpha Palmiers Hotel in Lausanne, that two GRU hackers managed to infect a Canadian official’s laptop via a close-range Wi-Fi attack. Via his e-mail box, they then infected and accessed the computer network of the Canadian Center for Ethics in Sport where the official worked. They retained access to that network in the course of more than a month.

The same hacking team that performed the September 2017 intrusions remained active until at least April 2018, when they were arrested in The Hague and deported after unsuccessfully attempting to hack into the Wi-Fi system of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). As disclosed by Dutch counter-intelligence who forfeited their personal belongings and laptops, the team had planned to return to Switzerland in order to try and apply the same method to hack into the Spiez Laboratory, which at that time was one of the labs analyzing the poison used on the Skripals in Salisbury. In the meantime, both hackers were indicted in the United States in March 2017, while in September 2018 Switzerland itself opened proceedings against them, as well as against a third, unnamed person.

While Dennis Sergeev and his subordinate team are not known to engage in cyber operations, and Sergeev’s career profile and domestic work travel itinerary suggest he is a traditional “human operations” security service operative, cross-functional operations appear to be a modus operandi for the GRU, if the four-member team captured by the Netherlands is any indication.

Trip 3: 30 October to 9 November 2017

Geneva-Chamonix

At the end of October 2017, Dennis Sergeev returned to Geneva. This time, he obtained a visa and landed directly at Cointrin Airport. This time again he returned for the night to Gaillard, probably to the same accommodation at Appart’City. The hotel was unable to trace his history of stays due to a change of management in July 2018, according to two receptionists we and our investigative partners interviewed.

But during this trip, Col. Alexander Mishkin and Col. Anatoli Chepiga, the accused perpetrators of the Novichok attack, were also present in Geneva, as our review of their travel records (previously disclosed by Bellingcat) indicate. The two men flew from Moscow to Paris on October 25, but they returned on an Aeroflot flight from Geneva to Moscow on November 4. They are likely to have traveled from Paris to Geneva by train or car, given that we did not find airline bookings for the Paris – Geneva leg. Notably, on October 31, Sergeev was geolocated near the Geneva railway station for a long period, just at the time when the second daily super-fast TGV train from Paris was scheduled to arrive.

There is no specific evidence of a meeting of the trio on the shores of Lake Geneva. But it would be implausible that three high-ranking GRU agents who have a history of joint travel would be in the same city at the same time without being in contact with each other.

We have not been able to establish the purpose of their joint operation. However, we have confirmed that on November 2, when all three were in town, Major General Sergeev’s telephone was located in the ski resort area of Chamonix between 11:30 a.m. and 3 p.m. A team-building mountain retreat, a surveillance operation, or something more sinister? To be investigated further.

Whatever the operation goals were, something unplanned must have happened. Sergeev had booked a return flight from Geneva to Moscow for 9 November 2017. On the afternoon of November 7, his phone was located in the neighbourhood of the Russian consulate. From there he left for the airport where – airline booking data shows – he bought a new ticket. On November 8, he flew to Moscow – a day earlier than expected.

The Russian Embassy in Switzerland via its spokesman Stanislav Smirnov told our reporting partners from the Tamedia Group that it was not familiar with any person having the name either Sergei Fedotov or Dennis Sergeev, and by a now-established tradition warned our Swiss colleagues to distrust any information coming from Bellingcat whom the embassy described as a “drainpipe for British authorities’ information”.

Trip 4: 23 December 2017 to 2 January 2018:

Geneva-Cologny-Paris

In December, the frequency of travel by the three undercover GRU officers increased again. On December 23, Alexander Mishkin flew from Geneva to Moscow after ten days in France and Switzerland. On the same day, Sergeev “took his shift” and arrived in Geneva.

He spent his time between the center of Geneva and the chic suburbs of Cologny and Collonges-Bellerive, a place of residence of many wealthy Russians on both sides of the Kremlin-friendliness divide. On that same day Anatoly Chepiga also arrived from Moscow, returning from Geneva to Moscow on December 30 with the evening flight. Sergeev, on the other hand, stayed in Geneva for New Year’s Eve and returned to Russia on 2 January 2018 – but this time not on a direct flight. He took the train to Paris via Lyon. From Paris-Charles de Gaulle airport he flew to Moscow that same evening.

Trip 5: 10 to 17 January 2018:

Geneva-Cologny

In January 2018, Sergeev returned to Geneva for one last trip before Sergei Skripal’s assassination attempt. But he stumbled into an unexpected logistical problem. The senior GRU officer landed late on the evening of January 10, his flight having been delayed. Unfortunately, after 10 p.m., the reception of the Gaillard apart-hotel is unmanned and the doors are locked. Cell tower data and the calls metadata show that that upon arrival at the hotel, Sergeev called its number several times without success. Then he made a phone call to “Amir”, his presumed handler in Moscow. After a short ride back to Geneva, Sergeev apparently booked a room in another hotel in Gaillard, just before midnight.

On January 13, Sergeev drove to the famed French ski resort of Les Gets, a 1 hour 40 minute trip through Thonon. He stayed there for about four hours and then returned to Geneva late in the evening. The next day he again drove to Les Gets: in total spending, more than three hours behind the wheel, to stay just two hours on-site. These consecutive trips to Le Gets must have been of critical importance, because during these two days, Dennis Sergeev made nearly fourteen calls to “Amir”, an unusually high number even by their standard.

Epilogue

Some of Sergeev’s movements within Switzerland have an unmistakable linkage to previously known GRU targets, such as the European offices of WADA and possibly the International Court for Sports. Those operations may have been in support or preparation of hacking operations performed by other GRU units, or they have have targeted human factors, such as preventing delivery of information by would-be whistle-blowers (indeed, shortly after Sergeev’s October 2017 trip to Lausanne, WADA announced it had just received a valuable database of Russia’s state-sponsored doping program).

Yet other movements cannot easily be matched to would-be cyber targets. Could some of these trips have been linked to the Novichok attack on 4 March 2018 in Salisbury, which occurred less than two months after his – and his two Salisbury-visiting subordinates – series of Swiss trips? There is no direct evidence of such connection, yet a new book on Sergey Skripal suggests a possible link.

Officially, Sergei Skripal, 68, retired in Salisbury after being pardoned by Russia in a spy swap in 2010. In actual fact, he admittedly continued to consult for Western secret services. In 2017, British journalist Mark Urban (who partnered with Bellingcat on the previous installment from this series) conducted several interviews with Sergey Skripal. Mark Urban reports in the book, and confirmed to us that at the end of June or beginning of July 2017, Sergey Skripal had to cancel a previously-scheduled interview on the grounds that he had to travel to Switzerland to meet with the local intelligence services. Contacted by our partners from Tamedia, Swiss Intelligence Service SRC said it does not comment on its operational activities and does not confirm or deny a possible meeting.

If Sergei Skripal was indeed in Switzerland in the summer of 2017 (and possibly for repeat visits later), the Russian secret services would have found out rather quickly. The GRU could then have sent Major General Sergeev to try to find out what the double agent had told the SRC, or to anticipate and prevent a follow-up meeting.

Since the failed assassination attempt at Salisbury, Dennis Sergeev has not traveled abroad. His telephone is inactive as of February 2019 – the time Bellingcat identified him publicly. It was the day after that publication that BBC journalists telephoned Sergeev’s wife in Moscow. When asked about her husband’s espionage activities, she just said that these stories are “a fairy tale”. Today, her phone number is disconnected.

Note: An earlier version of the article said that on 19 September 2016, GRU agents hacked the WADA computer network in Lausanne. In fact, on that day GRU agents hacked a laptop of a Canadian official from the Center for Ethics in Sport who attended a WADA-organized conference in Lausanne. Later they used the infected laptop to hack the network of the Center for Ethics and Sports. GRU had obtained access to WADA’s ADAMS database in August that year.