Balkan Gambit: Part 2. The Montenegro Zugzwang

In Part 1 of this investigation, Bellingcat and The Insider reported on Russia’s intervention in the parliamentary elections in Republika Srpska in October 2014. In Part 2, we investigate the evidence for a possible Russian involvement in the alleged attempted coup following the parliamentary elections in October 2016 in Montenegro.

Montenegro, July 2016

On July 14 2016, the Russian Foreign Ministry tweeted what appeared to be a series of messages threatening the tiny republic of Montenegro:

#Zakharova: We took note of Montenegro’s Prime Minister Milo Đukanović statements on “Russian propaganda” published on July 12

— MFA Russia ?? (@mfa_russia) July 14, 2016

#Zakharova: The current Montenegro authorities will bear full responsibility for the consequences of their anti-Russian stance @AmbRusME

— MFA Russia ?? (@mfa_russia) July 14, 2016

These vague threats came from Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova as reaction to Montenegro’s prime minister statement that “people from the lowest classes in the Balkans falling prey to Russian propaganda.” This remark, in turn, was precipitated by increasingly hostile Russian rhetoric in the months following Montenegro’s decision to orient itself westward, and to accept NATO’s invitation to join the alliance – a political decision that was controversial from a popular perspective (between 40% and half of the population is estimated to be opposed to membership in the military alliance).

On December 2, 2015, Kremlin spokesman Peskov threatened that Russia would take “retaliatory measures” in case Montenegro accedes to NATO, and Russian parliament threatened to freeze all cooperation projects with the small Balkan country. Ignoring these Russian warnings, Djukanovic signed an accession protocol with NATO in May 2016, permanently depriving Russia of its only potential ally with naval access to the Mediterranean.

Despite all the warning signals, when on October 16th 2016 – the day of general elections in Montenegro – Prime Minister Milo Djukanovic announced that a day earlier, the republic’s special services had arrested twenty Serbian citizens who had been planning a paramilitary plot to throw the mountainous republic into chaos – and potentially have him assassinated. Global reaction was skeptical. The alleged plot, described over the next several days by prosecutors, ministers, and local media, in at-times contradictory renditions, sounded too cartoonish to be reported on seriously. The authorities alleged that two dozen Serb and Montenegrin conspirators, acting under foreign guidance, conspired to purchase arms, infiltrate parliament on election day dressed as policemen, initiate a false-flag police attack on crowds of protestors gathering outside the building, arrest – or possibly even assassinate the Prime Minister, and install a government led by the Democratic Front – the staunchly anti-NATO, pro-Russia opposition alliance. The story barely registered in the global news flow.

It was not until Serbia – initially just as skeptical of Montenegro government’s claims – on October 24th arrested two Russian citizens who – Serbian police said – were in possession of counterfeit Montenegro special-police uniforms, €122,000 in cache, and sophisticated encrypted telecoms equipment – that global media started paying attention to this story. On October 26th 2016, Russia’s Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev travelled to Belgrade on a previously scheduled visit. In early November, the Guardian quoted an undisclosed source close to the Serbian government as saying that Patrushev had apologized to the Serbian government for what he described as “unsanctioned rogue operations”, an assertion that Russia later publicly denied and called a provocation.

The Serbian Plot

Several days after Patrushev’s visit, on October 29th, Serbian police discovered a cache of weapons near Prime Minister Vucic’s family home in Jajinci, along the route the would be riding to work. The arsenal was hidden in a car parked in the forest approximately fifteen meters from the roadside, and included a grenade launcher, four hand-grenades and more than a hundred rounds of 7.62 mm ammunition, as well as ammunition for automatic weapons.

The startling discovery sent Vucic into hiding until the investigation was completed; an understandable reaction in a country that had already seen one of its prime ministers killed by a sniper in 2003. In a written statement to media, Foreign Minister Ivica Dacic alluded that the masterminds of the attempted assassination may have been powers from outside the country, unhappy with Serbia’s sovereign choices. “History has proven that a Serb hand is always available for hire to do their dirty work”, Dacic wrote.

At a press conference on the next day, Vucic downplayed the weapons find being a sign of an imminent assassination plot, but said that warnings and threats have been registered in the preceding days, and confirmed that investigators suspected a foreign link, but said that threats were “not as concrete and proven as the ones for the coup attempt in Montenegro”. Vucic confirmed that he had “seen and heard hard evidence as clean as a whistle” in support of Montenegro prosecution’s allegations. “I heard the conversations with my own ears; I was not satisfied with the transcripts, I wanted to hear with my own ears. Only after I heard them, do I dare confirm this to you”, Vucic said.

In the evening of the following day, November 1 2016, Serbian police, acting on the trail of the cache discovery, found an automatic “Heckler & Koch” gun with ammunition plus 200 grams of TNT, mobile phone paired to detonators, and a pistol. The weapons were stored in the trunk of a stolen Renault Megan parked in a garage in New Belgrade.

In the following days, Serbian media published unsourced information that two Russian citizens had been repatriated to Russia following Patrushev’s Belgrade visit.

The Montenegro Plot: The Prosecution Narrative

In the first press conference since the October 16th foiled coup announcement, on November 6th, Montenegro’s chief special prosecutor Milivoje Katnić provided details of the alleged plot. Per his narrative, the plot involved citizens of Serbia, Russia and Montenegro, and had the goal of changing the political system in Montenegro.

The plan had been hatched, he said, by two Russian nationals, who had recruited a Serbian national – now a key indicted defendant – as the main organizer of the plot. Via him, further Serbian and Montenegrin nationals were recruited, with the goal to recruit up to 500 persons by election date.

The plan was, Katnić said, for dozens of conspirators to infiltrate crowds protesting in front of the Parliament building after 23:00 on election night. Then a certain politician from one political group (later defined as the anti-NATO, pro-Russian Democratic Front) would take the stage, and would trigger the crowd and the terrorists to storm Parliament by force. The infiltrated crowds would retain control over the building for 48 hours, and shooters would aim to assassinate Prime Minister Djukanovic. The end-game of the plot would be to change Montenegro’s political course and prevent its accession to NATO.

Katnic said a core group of fifty armed and trained terrorists with “military experience from fighting in third countries” had been recruited from within Montenegro, Serbia and Russia. He declined to confirm explicitly if that was a reference to Eastern Ukraine. Fifty automatic rifles and fifty pistols had been acquired to the criminals group.

The prosecution presented a three-minute video, provided by Serbian authorities, showing large quantities of riot police gear, Topcom and Motorola communication equipment, pepper spray, batons, gas masks, rolls of barbed wire, and drones; all allegedly captured in possession of plotters detained in Serbia at the request of Montenegro.

Katnic told reporters that the two Russians had been apprehended by Serbia’s special prosecution, and that they had been monitored surreptitiously by Serbia’s secret service and thus “the evidence could not be used in court”, as a result they “could not keep them in detention”. The two had already left the territory of Serbia, he said without specifying if they were in Russia.

The special prosecutor was careful to disconnect the accusations towards the suspected Russian nationals from Russia as a state. “We believe this was the work of Russian nationalists who wished to prevent Montenegro’s Euro-Atlantic integration. We are cooperating with both Serbia and Russia on this case”, he said.

However, Montenegro’s position on Russian state involvement changed after it transpired that one of the two Russians whom Montenegro was searching via the Interpol red-notice alert system, had travelled under a false family name on an officially issued, fresh Russian passport. Furthermore, it transpired that the person – Eduard Shishmakov – had until recently served as deputy military attaché in the Russian Embassy in Warsaw. According to a former head of government of another Balkan country familiar with the matter (speaking to us on condition of anonymity), both the Serbian and Montenegrin prime ministers had initially taken Patrushev’s assurances that the initiatives were those of Russian nationalists unrelated to the state, at face value, and the discovery that at least one of them was linked to GRU came as a shock.

Russia has denied the allegations and has refused Montenegro’s request to extradite the wanted Russian citizens. On March 2, 2017, Montenegro requested official legal assistance from Russia to permit the interrogation of the Russian citizens on Russian territory in the presence of Russian and Montenegrin prosecutors. Russian reaction to this request is still pending at press time.

Terrorists Turned Informants

Montenegro’s prosecution’s narrative rests primarily on witness testimony provided by two self-confessed plot participants: Montenegro national Mirko Velimirovic, who surrendered and became a police informant four to five days prior to October 16th, and Alexander Sindjelic, a Serbian former convict who had fought on the side of separatists in Eastern Ukraine, and was the leader of a staunchly anti-NATO, pan-Slavist and pro-Kremlin paramilitary organization called the Serb Wolves.

Sindjelic was initially detained in Serbia based on Velimirovic’s testimony fingering him as his recruiter to purchase weapons and to participate in the take-over of the parliamentary building on election night. After giving testimony to the Serbian Prosecution on November 6th, Sindjelic agreed to be transferred Montenegro to testify under a promise fora “protected witness” deal with both Serbian and Montenegrin prosecutors. On November 22, the High Criminal Court of Montenegro approved the suspension of his criminal liability in return for testimony on his alleged handlers.

Before the Montenegrin prosecution, Sindjelic recounted that he had been recruited by Russian citizens who he believed to be working for the special services. He in turn hired Bratislav Dikic, a former chief of Serbia’s Special Police, and the two organized a criminal group which had prepared riots after the elections in Montenegro on 16 October, with an ultimate plan to assassinate PM Djukanovic and forcibly seize power in Montenegro.

Sindjelic had also recruited a Montenegro-based contact, Miro Velimirovic to purchase weapons from Kosovo and recruit further local participants in the coup. By the time Velimirovic was expected to deliver the weapons, he was already collaborating with the police, and was instructed to report to Sindjelic and Shishmakov that the weapons had been bought. Shishmakov then asked for a photo of weapons as proof. The prosecution team borrowed weapons from Montenegro police to stage the photograph, and a photo was sent to Shishmakov. At the last moment, Sindjelic sensed something odd, and decided to replace Velimirovic with Dikic as key field organizer. Velimirovic had to hand over to Dikic the encrypted phone, upon which Dikic went to the safe house where he was told the weapons were stored. Montenegro policed were waiting there, and detained him.

Montenegrin Politicians

Based on Sindjelic’s testimony, the Montenegrin prosecution alleges that two leaders of the anti-NATO and pro-Russian Democratic Front, Andrija Mandic and Mladen Knezevic, were complicit in preparation of the coup, were planning to act in sync with the plotters on election night, and would be the ultimate beneficiaries of the coup. The special prosecutor has asked for them to be deprived of parliamentary immunity and to be indicted. Mandic and Knezevic have denied any link to, or knowledge of, a planned coup, and have challenged Sindjelic as a provocateur acting on behalf of their political foe Djukanovic. Despite an earlier consent to face Sindjelic in witness confrontation, both refused to meet him on March 20, 2017, citing the need for further time to prepare.

Denials and Skepticism

The leaders of Democratic Front, Bratislav Dikic and the Kremlin have all decried the Montenegro narrative as a fabrication aimed at discrediting the opposition and cementing the political power of Milo Djukanovic. Certain Serbian and Montenegrin commentators have also expressed skepticism to the official version. The key lines of attack are the fact that the prosecution in Montenegro has not shown evidence of the allegedly seized weapons, as well as the absence of hard evidence tying the opposition block to the plot.

Bellingcat and The Insider have analyzed all currently available open source data in order to assess the Montenegrin claims of Russian (state) involvement in the alleged coup, to assess the plausibility of the events as described in the Montenegrin narrative, and to identify further the Russian entities that may have been involved. This investigation does not aim to provide a conclusive assessment of all facts asserted by the Montenegrin authorities; its focus is to assess the plausibility of effective Russian intervention in Montenegrin domestic politics, in the context of a larger review of Russian active measures in Southern Europe.

Key alleged perpetrators

Alexander Sindjelic

Sindjelic claims he was initially approached by “Russian nationalists” whom he met while fighting on the side of separatists in Eastern Ukraine in 2014 and 2015. He was invited to travel to Moscow to meet with representatives of the “special services”. Sindjelic says his trip was arranged and paid by a person he knew as Eduard Shirokov, who met him at the airport arrival gate in Moscow and arranged for him to bypass passport control at Moscow airport, in order to not leave evidence of Sindjelic’s presence in Russia.

At a meeting on September 26th in a “luxurious apartment” in Moscow, Sinjelic says he met with Shirokov and another Russian, Vladimir Popov. They offered him the opportunity to participate in a plan to derail Montenegro’s accession to NATO–a concept that appealed to him ideologically, as he had engaged in pro-Russian and anti-Western political activism for years. During the meeting, Shirokov showed Sidnjelic a detailed architectural plan of the Parliament building in Podgorica, and outlined the plan for entry and takeover on election night. He then ordered him to buy weapons and ammunition, for which he provided funding, initially in cash, and subsequently via Western Union transfers.

Upon returning to Belgrade, Sindjelic says he contacted and recruited Velimirovic to procure weapons from Kosovo, and to rent a house in Podgorica, to be used by the conspirators for storage and as a safe-house. Sindjelic says that gave Velimitovic €25,000 in cash plus three boxes of ammunition.

Sindjelic and Velimirovic both testified that in early October, Shirokov and Popov arrived in Serbia and provided encrypted Lenovo telephones with pre-programmed numbers to Sindjelic, who passed one of them to Velimirovic. Police sources allegedly leaked to Montenegrin media that the Lenovo telephones were purchased online from a web-site based in Bulgaria.

Sindjelic claims he and and Dikic further recruited Nemanja Ristic, a former convict from Serbia who had also travelled to and fought in Eastern Ukraine.

Nemanja Ristic behind Serb nationalist politicians and Bratislav Dikic at anti-NATO rally in Belgrade

Nemanja Ristic taking a selfie with Lavrov in Belgrade, December 2016

Via encrypted VOIP calls, Sindjelic says he communicated instructions to Velimirovic and Dikic to infiltrate the parliament building at the end of election day, dressed as policemen but wearing blue ribbons as identifiers for their co-conspirators. They were to expect further instructions depending on outcome of elections.

Open Source Evidence

Open source data does not contradict, although it does not necessarily prove, Sindjelic’s version of events.

As his social media accounts (primarily on the Russian social network VK) show, Sindjelic has been a vocal opponent of NATO, the EU and, conceptually, of the West since at least 2013. His social network feed is replete with Russian-manufactured anti-US, anti-Ukraine and anti-EU imagery, and posts showing adulation of Vladimir Putin. He runs an online radio station dedicated to these same values.

Sindjelic did indeed travel to Crimea in early 2014 as part of the Serb volunteer dispatchment patrolling check-points in the days preceding the “referendum”; and he did travel to the Donbas in early 2015. In a Skype video conversation dated March 11, 2015, leaked by his counterpart in the chat, Sindjelic is seen bragging about an upcoming trip to Moscow to meet with “important people at the Ministry of Defense” to discuss the case of Serbian chetnik leader Zivkovic (who appears to be wanted by the GRU for unclear reasons). He is further seen asking for “more cash”, but his Belgrade-based counterpart, a Serbian political scientist, tells him this will be very difficult to arrange “following the Crimea situation”.

An analysis of Sindjelic’s VK timeline shows that he was an avid poster or re-poster, and averaged 7-8 posts per week. On September 25, 2016 – the day of his alleged meeting with Shishmakov and Popov in Moscow – he posted a selfie from an unknown location. It is impossible to geolocate the photo due to the generic interior background.

Notably, following this post, Sindjelic did not post anything until October 20th, 2016, when he re-posted a generic pro-Russia message (on October 20th Sindjelic was still at-large and being sought by Montenegro and Serbian police). This long gap of four weeks of social media silence is inconsistent with Sindjelic’s prior online behavior, but consistent with a period of working on a project that required full focus and minimum traceability.

On October 19th, 2016, Montenegrin newspaper Dnevne Novine and several news sites obtained leaked transcripts and recordings of alleged phone calls between Sindjelic and Dikic (transcripts only), and Sindjelic and Velimirovic (transcripts and audio).

The phone call between Sindjelic and Velimirovic was ostensibly made on the day before election date. In the call, Velimirovic expresses concerns that he has not received clear instructions on the expected course of events the following day, and complains he has not yet met with the person who is supposed to give such instructions. The translated audio call is below:

Vocal comparison between Sindjelic’s voice in this call and his (authenticated) voice in a Skype video call, confirms that the person on the call is indeed Sindjelic. The balance of audio levels and bandwidth implies that the recording device/app was on the telephone originating the call, that is Velimirovic. This would be consistent with the prosecution’s narrative that at the presumed time, Velimirovic was already a police informant.

The transcript of the call between Sindjelic and Dikic suggests it was made ostensibly a day before election date. In the call, Dikic complains he cannot reach via phone someone whose phone, according to Sindjelic, is in roaming. Dikic was to infiltrate parliament dressed as policemen, then wait out the result of the elections, and not to act in case either the opposition Democratic Front block wins, or if Djukanovic relinquishes power voluntarily (which the parties on the calls appear to hope will be the actual outcome). They make a reference to “politicians” who appear to be part of the plan. The call also explicitly refers to the “Russians”.

We have talked to the Dnevne Novine’s political editor who obtained the transcripts, and he stands by the credibility of his source. Notably, Dikic’s lawyer, while not confirming the authenticity of the transcripts, accused the prosecution of permitting “frivolous leaks to the media”, thereby indirectly adding credibility to the content.

The leaked transcripts have not been authenticated by the Montenegrin authorities, and the Minister of Interior suggested they may be part of a distraction campaign. This may be a sincere warning, but it may also be the result of concern of actual leaks of an ongoing investigation, especially at a time when the nature of the foreign (Russian) link was still undetermined.

The content of the transcripts tallies with Sindjelic and Velimirovich’s testimony to prosecutors that in case electoral victory was claimed by the ruling party, a separate group of conspirators, mingled with the crowd of expected protestors, would trigger a storming of the Parliament building. Per Velimirovich’s testimony, his group of faux policemen would have then reacted by firing shots towards the crowd, thus initiating chaos and encouraging the crowds to take over the building, and creating conditions for a take-over of power by members of the Democratic Front.

Russian nationals

Eduard Shishmakov

Eduard Shishmakov travelled to Serbia with a Russian passport under the name Eduard Shirokov, and this was the name under which Montenegro issued his red alert warrant via Interpol. On February 19, 2017, the Montenegro special prosecutor announced that Shirokov’s real name was Shismakov, as discovered via a tip received from the Polish partner services.

Copies of two concurrently valid passports issued to the same man appear to use two different family names. Notably, the passport in the name Shirokov was issued in August 2016, one month before the alleged recruitment meeting in Moscow. The authentic Shishmakov passport was issued in 2012.

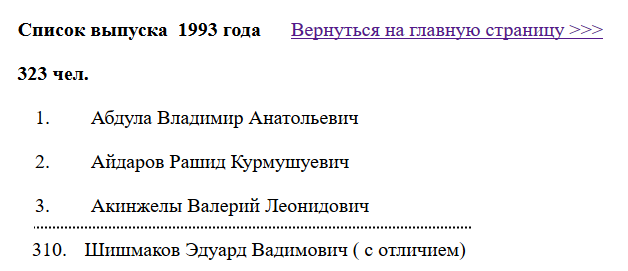

We have confirmed that Eduard Shishmakov is indeed the actual name of the person wanted via Interpol. Shishmakov was born in 1971 in an army officer’s family, and finished secondary school at a Soviet military base school in Halle, East Germany. In 1993 he graduated “with distinction” from the Black Sea Military Navy Institute in Sevastopol.

Extract from Military Navy Institute graduation roster 1993, showing Shishmakov under #310

Following navy school, he studied at the Military-Diplomatic Academy at the Russian Defense Ministry, a training institution for military attachés as well as GRU’s school for intelligence officers operating under diplomatic cover. Shishmakov’s course mates include, among others, Igor Kostyukov – GRU’s first deputy chief, and Sergey Zapadaev, commander of Military Intelligence Unit 62986, identified by Ukraine as a key GRU player in Russia’s intervention in Eastern Ukraine.

As of 2013, Shishmakov was serving as naval military attaché at the Russian embassy in Warsaw. On January 24, 2014, Shishmakov took part in a high-level security meeting with the Polish Security Council (BBN). On the Russian side, the meeting was also attended by the vice-secretary of Russia’s security council Yevgeniy Lukyanov (deputy to Nikolai Patrushev), as well as by the Defense Research Director of the Kremlin’s Russian Institute for Strategic Studies Grigoriy Tisschenko. A Russian version of the report on meeting by the Russian Security Council omits the name of Shishmakov.

In November 2014, Polish media reported that a Russian diplomat was declared persona non-grata and expelled. In March 2017, Polish authorities confirmed to Sky News that that diplomat was Eduard Shishmakov. The Russian embassy in Poland has not removed Shishmakov from the list of embassy officers, which is standard intelligence practice to disguise the identity of outed spies.

Eduard Shishmakov (right) at event commemorating Soviet Army’s victory over Nazi Germany, Poland, March 2014

Shishmakov was accused by Polish military counter-intelligence of recruiting a Polish officer working in the Ministry of Defense, Lt Col. Zbigniew J. According to a court verdict from May 2016 sentencing the Polish officer to eight years, he was tasked to provide GRU data on hundreds of Polish military personnel with history of misdemeanors, past criminal indictments or other disciplinary problems. These were deemed easier targets for recruitment as spies. The colonel confessed in court that he had received a payment of 17,000 Zloty (€5,500) and been given a special encrypted phone to communicate with Shishmakov.

At the same time in October 2014, a Polish-Russian lawyer Stanisław Sz was arrested and indicted for economic espionage in favor of Russia’s GRU. According to his indictment, he was recruited and handled by the same GRU officer as Lt. Col .Zbigniew J, thus presumably by Eduard Shishmakov.

Polish special police arrest Col. Zbigniew S., October 17, 2014

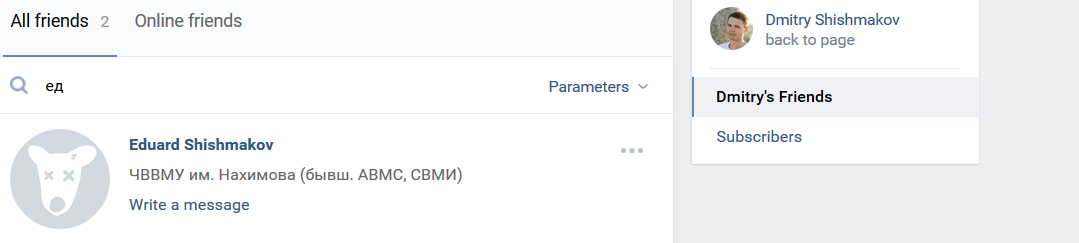

Eduard Shishmakov had a social media account on the Russian social network Vkontake (VK); which was deleted at some point in late 2016. We were able to identify his deleted account among the friends of Dmitriy Shishmakov, whose patronymic is Eduardovich, which suggests this may be his son. Dmitry Shismakov is an IT entrepreneur and from St. Petersburg.

Eduard Shishmakov has a listed residential address in St. Petersburg. This address, according to our sources, belongs to a corporate apartment compound owned by GRU.

The GRU apartment compound in Pavlovsk, St. Petersburg, where Shishmakov is officially domiciled.

Dmitriy Shishmakov has refused to answer our questions about his relationship with Eduard Shishmakov and the latter’s scope of activities, and has denied to another publication that he is even related to the Eduard Shishmakov wanted by Interpol. However, it appears beyond doubt that he is related to the GRU officer Shishmakov, as evidenced in this photo of the two, as well as from the visual similarity between the young Eduard Shishmakov and the young adult Dmitriy.

Dmitriy Shishmakov was visiting Poland at the time Eduard Shishmakov served as Navy attaché there, as seen from a photo of him visiting Krakow that was posted on his Facebook timeline in June 2014.

Following our attempt to interview him, Dmitriy Shishmakov deleted this photograph from his timeline along with all of the photographs from his visit to Poland.

Eduard Shishmakov’s mobile number has been switched off since disclosure of his identity in mid-February. His home number rings, but is never answered.

Vladimir Popov

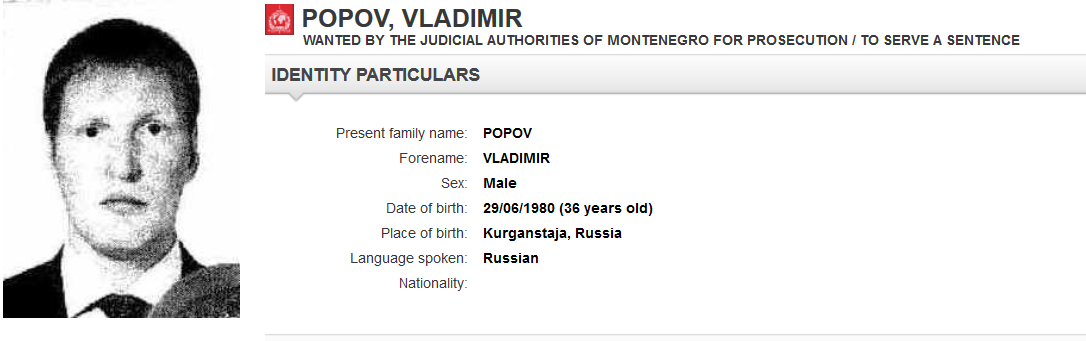

Popov’s role, if separate from that of Shishmakov, is not explicitly described by the prosecutor. He was described as one of the two Russian nationals who recruited Sindjelic in Moscow. He is assumed to have travelled to Serbia in October 2016, as the Montenegrin authorities had access to his passport photo which was used for the Interpol warrant.

We have not been able to receive confirmation of Popov’s background and/or education, and whether this is indeed his real name. However, a social network account in the name of a person with the same name and birthdate existed on VK until March 4th when it was deleted. However, independent Russian news site MediaZona retrieved a photograph of the account holder that bears strong similarity to the Interpol photograph.

A review of Popov’s timeline prior to deletion showed that he travelled and posted frequently from European locations including Germany, Switzerland, Georgia, Turkey and Greece. He appeared to have participated in several international conferences on marine insurance topics, and his account alleged he worked for a now-defunct marine insurance publication.

A Moldova-based publication alleged that a person with the same name and birthdate was tracked by Moldovan security services during a visit to that country in May/June 2014, where he met with Gagauzian separatists and anti-EU activists. The national Security Service of Moldova has not responded by press time to our request for confirmation.

A source within the Bulgarian border control service has confirmed to us that a person with the same full name and nationality, and using a Schengen visa, was registered as travelling into and out of Bulgaria on October 10, 2016.

GRU vs. Russian Nationalists

There appears to be no doubt that Eduard Shishmakov was present in Serbia in October 2016, as Serbian and/or Montenegrin authorities had access to his freshly issued, false-name passport which they submitted to Interpol in October 2016.

There appears also to be no doubt that as of his expulsion from Poland in October 2014, Eduard Shishmakov was in active service with the GRU. Following his outing as a Russian spy, it is unlikely he could have travelled under his real name without being monitored by Poland’s partner services. Based on his access to a new passport under an alias (which is not permitted to civilians under Russian law), it is highly improbable that Shishmakov had left GRU service as of August 2016. This fact is circumstantially supported by his current registered address being at a GRU-owned residence.

His prior modus operandi in Poland, in particular his (or GRU’s) preference for recruiting targets with a felonious background, and his communication methods appear consistent with the alleged methods used in Serbia and Montenegro.

Furthermore, the issuance of a passport under a false name in August 2016, only two months before travelling to the Balkans on the eve of elections in Montenegro, adds further credibility to the hypothesis that Shishmakov was fulfilling a GRU mission targeting interference with the Montenegro elections.

There is less hard evidence for Vladimir Popov’s link to Russia’s intelligence services. His role, if any, is likely to have been junior to Shishmakov’s. His trip to Bulgaria may have been linked to the delivery of the encrypted telephones, which according to investigation leaks in Montenegro media were purchased via a Bulgarian website.

Public-Private Partnership?

As we wrote in Part 1 of this investigation, following his successful paramilitary intervention in Eastern Ukraine, Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofeev reveled in a brief period of pan-European hyperactivity as a deniable proxy for the Russian state. Based on multiple sources, in late 2014, the Kremlin restricted his geopolitical power-of-attorney to the Balkans.

In the period of 2014-2016, in addition to his intervention in the elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Malofeev was linked to media acquisitions and political engineering in Greece; an attempt to take over strategic media, arms manufacturing and telecommunications companies in Bulgaria, with the goal to use them to sponsor a new, pro-Russian political party; and an acquisition of a large media group in Serbia. In pursuing his regional strategy, Malofeev has worked in close cooperation with Kremlin’s quasi-academic think tank RISS, headed until recently by General Reshetnikov, KGB’s former regional resident for the Balkans. RISS and Malofeev have so far been linked to joint political engineering in at least Bosnia Herzegovina, Greece, and Bulgaria.

Given the role of a regional firewall assigned by the Kremlin to Malofeev, it would be unlikely for any active measure, especially one having the blow-back potential of a political coup, to be funded and conducted directly by Russian intelligence services without his mediation.

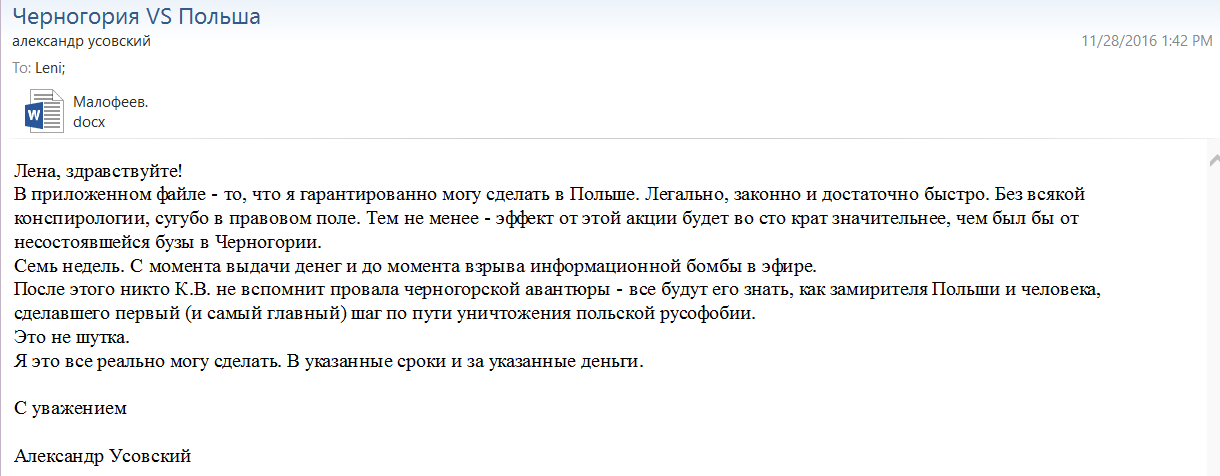

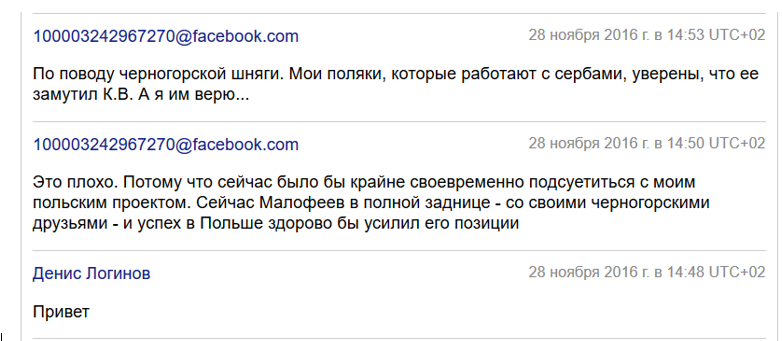

The recent email and VK hack of Alexander Usovskiy, who freelanced for Malofeev’s active measures in CEE in 2014 and 2015, appears to provide circumstantial evidence that the Russian oligarch was indeed involved with the failed Montenegro coup. In a series of emails and Facebook messages, Usovskiy appears convinced that Malofeev was behind “the unnecessary Montenegro fiasco”. In one email from November 28, 2016 to Malofeev’s close associate and TV Tsargrad chairwoman Alena Sharoykina, Usovskiy bluntly proposes a new initiative that will wash the egg off his face following the Montenegro failure.

“In the attached email is what I can guarantee in Poland. Legal, legitimate and quite fast. Without any conspirology, fully within the legal domain. And yet, the effect of such measure will be hundred times bigger than would have been from the failed mess in Montenegro. Seven weeks. From the moment of allocating the money until the explosion of the information bomb. After this, no one will remember K.V. [initials of Konstantin Valereevich Malofeev] with the failure of the Montenegro adventure – everyone will remember him as the pacifier of Poland and the man who made the first step on the way to destroy Polish Russophobia. This is not a joke”

Alena Sharoykina did not reply to Usovsky’s proposal. She has refused to answer Bellingcat’s written questions about this email and its context.

Malofeev and Montenegro

On September 10-11, 2014, at an international gathering in Moscow devoted to “traditional family values” and sponsored by Malofeev, the billionaire hosted Strahinja Bulajic, a Montenegrin MP known for his anti-NATO positions. Several months later, Bulajic became a member of the leadership of the Democratic Front coalition. Throughout 2015 and 2016, Bulajic advocated and organized protests against the “NATO mafia” and called for Djukanonvic to resign. Throughout 2016, Malofeev’s Tsargrad TV gave extensive airtime to DF leaders Andria Mandic and Milan Knezevich (both currently key suspects in the alleged Montenegro coup). In a Tsargrad TV interview from February 2016, Mandic predicted perpetual street protests and violent conflicts in Montenegro in case there would be no referendum on NATO membership. During this interview, Mandic said that at his meeting with Duma speaker Sergey Naryshkin, he was promised that pro-Russian forces in Montenegro “can count on Russian support”.

Konstantin Malofeev’s geo-commercial activities inside Montenegro were restricted by Montenegro’s adherence to EU sanctions, resulting in his inability to travel to the country. Nevertheless, during the Orthodox Easter celebrations in April 2015, he sponsored the bringing of the Holy Fire to Montenegro, earning the blessing of Montenegrin arch-bishop Amfilohije. “If Malofeev has sinned [in Ukraine], the Holy Fire has saved him”, Amfilohije said at the time. Malofeev supported the Holy Fire procession once again in 2016, this time also sponsoring a trip to Jerusalem for none other than the DF’s Andrija Mandic.

Malofeev had previously used the Orthodox Church in Ukraine as cover and conduit in preparation for the secession of Crimea and separatists revolts in Eastern Ukraine. In January 2014, he sponsored the bringing of the “Gift of the Magi” to Ukraine’s Orthodox Church, which welcomed it with gratitude similar to Amfilohije’s. Malofeev sent his chief-of-security, then unknown ex-FSB colonel Igor Girkin, to accompany the gift’s procession from Kiev through Crimea and onto Eastern Ukraine. During the procession, Girkin transformed into “separatist commander-in-chief Strelkov”, and did not return from his successful business trip until August 2014.

Malofeev’s interaction with the Montenegro’s arch-bishop Amfilohije has been similarly symbiotic. After blessing Malofeev, Amfolohije negotiated to sell him a TV station in Montenegro. The mitropolit has been one of the most vocal anti-NATO and pro-Russian public figures in Montenegro, repeatedly calling for the dropping of anti-Russian sanctions.

Given his staunch anti-Djukanovic and anti-NATO militancy, it appeared counter-intuitive that in the evening of October 16, 2016, archbishop Amfolohije called on the public not to gather in front of Parliament to protest the outcome of elections, but to stay at home. This unexpected mellowness even caused special prosecutor Katnic, in his statement announcing the foiling of the coup, to thank Amfolohije as contributor to peace in Montenegro.

Notably, at the time of Amfolohije’s public call for restraint, Dikic and Velimorovich were in police custody, and Sindjelic and his handlers would have known that the plot had been outed. Any further adherence to the previous plan for violent protests would have been futile, and become a liability for the organizers.

RISS and Montenegro

On November 28th, Alexander Usovskiy messaged a nationalist contact to inform him that

“my Poles who work with the Serbs, are convinced that K.V. is behind the Montenegro mess….Malofeev is now in a complete shithole – thanks to his Montenegro friends”

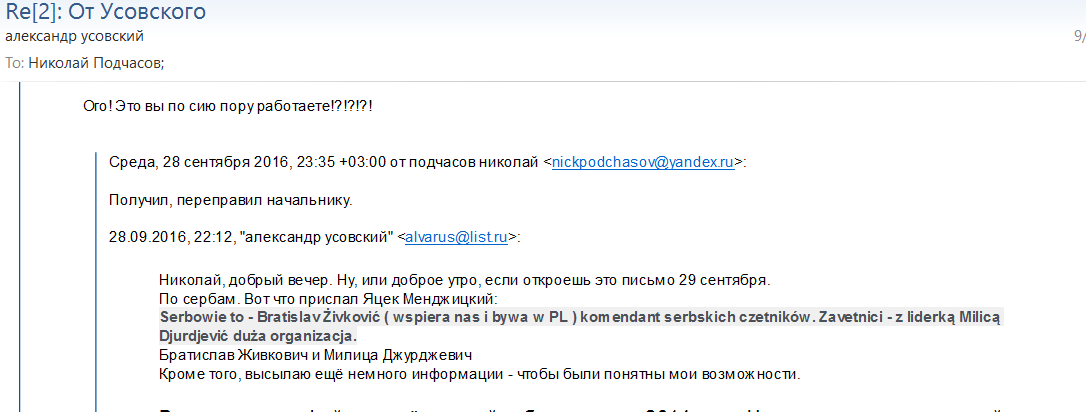

Usovskiy’s reference to “My Poles who work with the Serbs” appears to correlate to an email he sent two months earlier to a RISS employee, Nikolay Podchasikov. The email included names of two Serbian nationalists, including Zivkovic – the leader of the Serbian chetniks referenced by Sindjelic in his Skype call. From the message context, it appears that these names were requested by Podchasikov’s boss, the Chief of RISS’s Balkan desk, Nikita Bondarev. Usovskiy wrote that the Serbian names were provided by his Polish sub-contractor Jacek Medrzycky, the organizer of Malofeev-sponsored anti-Ukraine pickets in Poland in 2014. Usovskiy further asked if these are “the right Serbs”, and if so, when he could “come for the money for the gathering”.

It is not clear what gathering Usovskiy is referencing.

RISS had been intensively analyzing and commenting on the political situation in Montenegro in the months preceding the elections. In February 2016, Nikita Bondarev predicted a post-election scenario which chillingly resembled the planned chaos described in Sindjelic and Velimirovic’s confessions: crowds of protesters attempting to storm the Parliament building, police dispersing them with rubber bullets, yet protesters against Djukanovic persisting. Bondarev further predicted a hypothesis in which Djukanovic loses the support of EU and NATO, however, for that to happen, in his words:

“The process of protests activity in Montenegro must move to a different stage. Currently, we see peaceful protests, but they may escalate to something similar to what happened in Kiev on the Maidan”.

Bondarev further warned that the only way to ensure a peaceful resolution of political tensions in Montenegro required Djukanovic’s government’s resignation.

“The government should listen to the people and compromise, in order to prevent unnecessary casualties and submerging the country into an even bigger chaos”

RISS’s chairman, General Reshetnikov has been an unrestrained critic of PM Djukanovic, at one point, at a joint event with archbishop Amfolohije, calling the PM “a traitor who will answer for his treachery to Russia on Judgment Day”, and repeatedly predicting an “anti-Western rebellion on Montenegro if Djukanovic wins the elections”

General Reshetnikov and Archbishop Amfolohije, November 2014

On October 12, 2016, Bondarev and Reshetnikov hosted in Moscow the “Atamans of the Balkan Cossack army”, a pro-Moscow union of veteran-volunteers from recent wars, including Eastern Ukraine. The union was established a month earlier in Kotor, Montenegro, and by its own description, was a Russian paramilitary outpost on the Balkans. “Supreme Ataman” of the army became Victor Zaplatin, Balkan Representative of the Donbass Volunteers’ Union, and one-time commander of Igor Girkin during their stint as Serb-side volunteers in the Bosnian war in 1991-1992. In November 2015 in Belgrade, Zaplatin and Malofeev’s associate Alexander Boroday established the Serbian branch of the “Donbass Volunteers Union”.

Reshetnikov (center), with Bondarev (left), host Serb chetniks and Donbas military commander Zaplatin (second right)

Given that the alleged coup did not materialize, it is uncertain what role, if any, the “Balkan Cossack Army” was meant to play in post-election events in Montenegro, and whether Usovskiy’s search for Serbian nationalists on behalf of RISS in September 2016 was linked to any such plans. Our attempts to receive comments from RISS remained unanswered.

Several days after the public disclosure of the failed coup, and the extraction of the Russian citizens from Belgrade, President Putin announced the replacement of RISS’s chairman Leonid Reshetnikov with Mikhail Fradkov. Sources close to RISS confirmed to us that Reshetnikov was due for retirement on his 70th birthday, which would have been in February 2017. The decision to announce the change in early November 2016 appeared surprising, especially given the fact that Fradkov, a former chief of foreign intelligence, had been previously earmarked as chief of Supervisory Board of Russian Railways.

Alexander Sytin, former colleague of Reshetnikov who was fired in 2014 following his statement criticizing Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, told us that he believes Reshetnikov’s role in Montenegro’s events has been one of a “ideologue and consultant”:

“He is very close to Milosevic’s brother and widow. He has a large network on the Balkans, indeed primarily in Bulgaria and Greece, but certainly with a lot of contacts among the “former” Yugoslav secret service operatives of his generation. The ideas to conduct provokatsyas – in Ukraine, Moldova, Greece (he was an active supporter of Tsipras) – are among Reshetnikov’s favorite ideas. I believe that in this case, the main communication [with the State] went not along RISS lines, but, for instance, via the Security Council where Reshetnikov is a consultant, as well as his own contacts at the President’s administration. It’s most likely that he offered this idea: to organize a coup in Montenegro, and might have pointed to possible executors; if not at the level of people, at least at the level of pro-Russian organizations. The actual plans were developed, of course, by others. He could not have taken upon himself the operative activity, although he always longed for the days of his active service as rezident in Bulgaria and Greece”

To our question if it is conceivable that the alleged coup might have been a purely private initiative – for example by Konstantin Malofeev, using Reshetnikov’s network without coordination with the Kremlin, Sytin was dismissive: “No one would dare conduct international geopolitical activity without coordination with the Kremlin. Such initiatives would be severely punished.”

Our attempts to receive a comment from Konstantin Malofeev and Gen. Reshetnikov on the Montenegro events remained unanswered. When first approached with questions about Montenegro, Malofeev’s TV station Tsargrad and related media outlets responded with a barrage of ad hominem reports against the authors of this report.

***

On January 31st 2017, Putin met with Leonid Reshetnikov to thank him for his work as head of RISS.

“You did a lot in the past 7 years”,

Putin said to Reshetnikov. The outgoing general responded:

“I want to say that over these years we worked as best we could to implement and realize your line in foreign policy. This was always our cornerstone– the line of Russia, the line of our President”

Correction: an earlier version of the story mistranslated a word in the summary of the Skype call between Serb political scientist Vencislav Bujic and Sindjelic. In fact, the latter asked Mr. Bujic for more “cash”, not for “munitions'””. The translation in the embedded video was and is correct.