Coercion and Corruption: Following Russia's 2016 Election Season

Russia’s parliamentary elections on September 18th come at a critical moment for Vladimir V. Putin, whose party, United Russia (Edinaya Rossiya), is losing popular support amid economic crisis. Though Putin himself has remained insulated from national dissatisfaction, United Russia has not, threatening the party’s dominance and Putin’s own interests. After all, it is from United Russia that Putin’s successor, should he choose not to run in 2018, will come; and it is United Russia’s deputies in the Duma, currently possessing a majority, who will push through controversial bills such as this summer’s anti-terrorism laws. The upcoming elections offer Putin a chance to re-legitimize his party and protect his interests in the parliament.

With stakes that high, it is unsurprising that attacks on the opposition and instances of electoral misconduct have spiked in recent months. But few individuals, if any, are being punished for it. Russia’s accountability vacuum is such that even with a reform-oriented official like Ella A. Pamfilova at the helm of the Central Election Commission (Tsentral’naya izbiratel’naya komissiya), those guilty of intimidating opposition politicians or engaging in electoral misconduct are unlikely to be prosecuted or penalized. It’s a situation made all the more egregious by the frequency with which perpetrators are caught on camera by journalists, bystanders, politicians, and activists.

Coercing Russia’s Opposition

Violence against the opposition, while mostly non-lethal, is becoming a norm in Russia. A report released this summer by the Center for Economic and Political Reforms (Tsentr ekonomicheskih i politicheskih reform) found that, halfway through the year, 2016 was already well on its way to becoming the most violent year for the opposition in recent history: while 2014 saw 60 attacks, 2016 had already witnessed 55 by the end of June.

Overwhelmingly, perpetrators of political violence belong to ultra-conservative elements in Russian society. Though these include Cossacks, for the most part, it is so-called national liberation groups that carry out attacks against the opposition. Organizations like Antimaidan and the National Liberation Movement (Narodno osvoboditel’noe dvizhenie, or NOD), see Russia as being perpetually at war with the West and Russia’s opposition as a fifth column. Opposition leaders such as Aleksei A. Navalny of the Party of Progress (Partiya progressa) and Mikhail M. Kasyanov of the People’s Freedom Party (Partiya narodnoy svobody, or PARNAS) are regularly harassed on the grounds that they serve foreign masters.

Throughout 2016, assailants have exploited knowledge of their targets’ campaigning schedules, which allows them to pursue candidates, most notably Kasyanov, across the country. From February to August, Kasyanov was harassed or attacked a total of six times. Of these instances, three took place in, or in front of, hotels where Kasyanov was staying; one occurred in an event hall he was due to speak at; and another saw him confronted in a restaurant he was dining at.

Other opposition politicians, including Navalny, who was assaulted after exiting a Novosibirsk courthouse in March and ambushed at an Anapa airport by Cossacks in May, have also had their itineraries used against them. More worryingly, some opposition figures, like PARNAS’ Aleksandr Bragin and Solidarity’s (Solidarnost’) Igor Ivanov, have been viciously assaulted in front of their very homes. In the former case, the attackers laid in wait for Bragin, who was attacked en route to his car; in the latter, Ivanov was lured out of his apartment when the assailants called him, claiming to have accidentally damaged his car.

Screenshot from a video posted by Alla Naumcheva showing attacks from the NOD and SERB movements. (source)

Attackers’ tactics include throwing eggs, feces, cakes, and condoms (a humiliating experience for any public figure), striking with blunt objects, punching, kicking, and even firing non-lethal “traumatic pistols.” One particularly creative incident involved an attempt at forcibly putting a quilted jacket saying “Misha is a thief” onto Kasyanov, and underscored the often-theatrical dimension of political violence in Russia.

Whether by means of violence or humiliation, attackers aim to coerce opposition politicians into withdrawal from the public eye at a time when visibility and outreach are key to political success. In Kasyanov’s case, safety concerns led to the cancellation of at least one campaigning event, in Nizhny Novgorod.

Subverting Russia’s Democracy

Ultimately, it is impossible to deter all of Russia’s opposition politicians using coercion, an obstacle circumvented by subverting the democratic process itself. Electoral misconduct takes many forms, and seems to be especially pervasive this election cycle: by September 9th, 1,330 complaints had been registered with Golos, an election-monitoring organization threatened with liquidation by the Ministry of Justice.

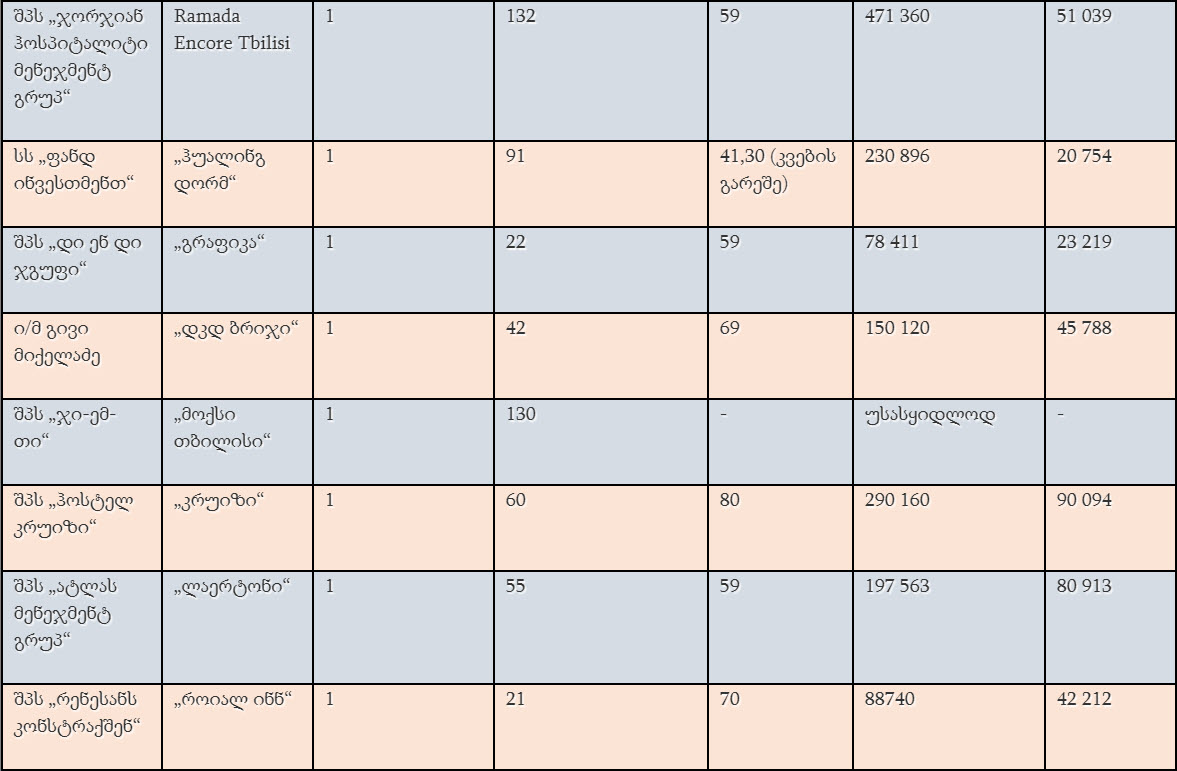

For one, United Russia’s dominance enables candidates to use government resources for campaigning, a violation that is technically grounds for de-registering a political candidate, with impunity. Aware of their immunity, candidates, like Gennady G. Onishchenko and Ivan M. Teterin, tend to do so openly.

In August, Onishchenko was caught on video meeting with voters in a governmental social welfare center in Moscow. In the video, the center’s director, Ilya R. Bestavashvili, made no secret as to the fact that Onishchenko was holding a campaign event, and even invited the journalist filming to register as an Onishchenko supporter. When he refused to, Bestavashvili promptly asked that someone call the police. The following day, Yabloko candidate Dmitry G. Gudkov filed a complaint against Onishchenko with the Central Election Commission, which has yet to exclude the United Russia candidate from the September elections. Onishchenko also appears to have enlisted public service workers to put up campaign ads around Moscow.

Screen capture of a meeting with Bestavashvili and Onishchenko in Moscow. (source)

Teterin, another Moscow candidate, isn’t particularly subtle, either. Using his position as president of the Academy of the Ministry of Emergency Situations’ (Ministerstvo po chrezvychainym situatsiyam) State Firefighting Service (Gosudarstvennaya protivopozharnaya sluzhba), Teterin secured a fire truck in order to cut his travel time in half when campaigning.

Footage captured Teterin driving the fire truck down ulitsa Akademika Korolyova and meeting with the residents of house 8. “I suggest that, in these elections, you support our president,” Teterin told them, conflating Putin and his party. After all, he reasoned, “the president should have [a majority in] the Duma in order to execute his decisions.” Demonstrating United Russia’s legal immunity, a nearby policeman refused to hear out the formal complaint of the opposition activists filming. Like Gudkov, the Party of Progress’ Nikolai N. Lyaskin has filed a complaint against his United Russia opponent. Like Onishchenko, Teterin has yet to be de-registered as a candidate.

Screen capture of a fire truck going down ulitsa Akademika Korolyova in Moscow en route to a meeting with voters. (source)

A tweet, posted several days before, suggested that the fire truck incident hadn’t been Teterin’s first offense that week. On August 23rd, Teterin attended the unveiling of a Moscow playground, an accomplishment that he attributed to United Russia, not the government, whose funds had been used to build it. A similar situation occurred on the 20th, when United Russia’s Vladislav Lyumin joined party volunteers in restoring a Novosibirsk playground. When locals approached the team, filming them and pointing out that bribing voters (such as by “providing services free of charge or on favorable terms”) is illegal, the policemen present tried to de-escalate the situation and send the locals on their way rather than acknowledge the violation taking place. Meanwhile, the volunteers called the locals (their constituents) “scum” and “shameless,” with one advising that the woman filming should “get off the road, fat creature.”

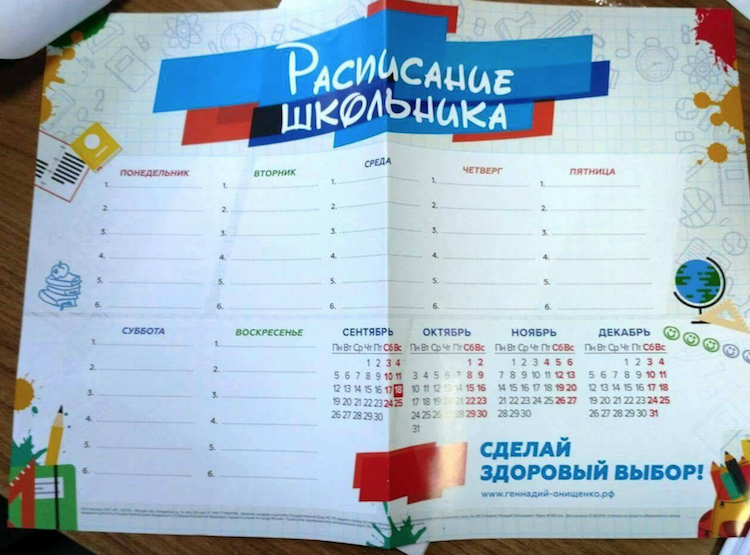

Even less subtle was United Russia’s drive on September 1st, the start of the academic year in Russia. The “Day of Knowledge” was marked by the party’s efforts to insert itself into the first day of school across Russia, in clear violation of a law prohibiting party activities inside state or municipal educational institutions. In Moscow, schools 820 and 1515 distributed calendars to schoolchildren featuring the slogan “Make the sound choice!” and a link to Onishchenko’s website. School 31 in Kaliningrad celebrated by parading with United Russia flags, while in Berdsk, children received schedules with the United Russia logo. Meanwhile, the headmaster of a Moscow school took a unique approach to abusing his authority to help United Russia, conscripting schoolchildren to campaign for candidate Pavel G. Zelenkov.

Photograph of a calendar given to schoolchildren at School No. 820 in Moscow by United Russia. (source)

In a sign of a topdown propaganda campaign, members of the Sverdlovsk regional government were instructed to promote United Russia during school visits on September 1st, giving prepared speeches that outlined the government’s accomplishments. “It is absolutely necessary to come to the elections and vote,” an excerpt from the speech read. “It is absolutely necessary to support President Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin and the president’s party. Only then will our plans … materialize.”

As indicated by the high number of complaints registered with Golos, misconduct is taking place on an astonishing scale. Some incidents suggest that election commissions themselves may also be compromised. In May, Natalia N. Ovcharenko, a member of a vote-counting commission in Sevastopol, harassed people registering to vote, telling them to support United Russia’s Dmitry A. Belik. When criticized by a volunteer, she warned that “Dmitry Anatolyevich will speak to you later.” Whether credible or not, Ovcharenko’s threat speaks to the fact that corruption is present throughout Russia’s electoral institutions, and represents a potent force benefitting United Russia, whatever Pamfilova says.

Speaking at the Carnegie Moscow Center in July, researchers Andrei Kolesnikov and Boris Makarenko predicted that after the protests of 2011-12, creating an air of legitimacy would be chief among the government’s priorities in September. Between the incidents described above and the recent coup de grâce dealt to Russia’s Levada Center for its research on United Russia’s falling support, there is little legitimacy to speak of so far. With the 2016 election season marked by acts of violence, attempts at intimidation, and blatant violations of the law, all highlighting the Russian government’s disregard for its own legal regime, September 18th is unlikely to end with a victory for the opposition.

Loose Threads

Going forward, there are multiple routes for additional open source investigation into these incidents and into this month’s parliamentary elections in Russia. Some of these topics that need additional investigation, and are topics for aspiring open source researchers looking for a subject to research, are…

- Are there any particular individuals who can be tracked among multiple videos showing attacks against opposition figures?

- Can we monitor potential instances of “carouseling” (transporting buses of people to vote at multiple locations) through live video streams during the elections?

- On the 18th, will election monitors be subject to the same violence encountered by opposition politicians? As with carouseling, can we track the treatment of monitors on election day?

- Are there Central Election Commissions that have responded to local complaints about electoral misconduct? In these voting areas, how well did opposition parties fare?