Burning Villages: Violence Escalates as Myanmar Military Reacts to Territorial Losses

Over three years since the February 2021 coup that toppled a democratically elected government in Myanmar, the military junta is losing large swaths of land to anti-coup resistance fighters and ethnic rebel groups. Several opposition forces have formed alliances, taking back key junta strongholds. A coordinated offensive ‘Operation 1027’ that began on October 27, 2023 in Shan State, on the eastern border with China, has now spread across the country.

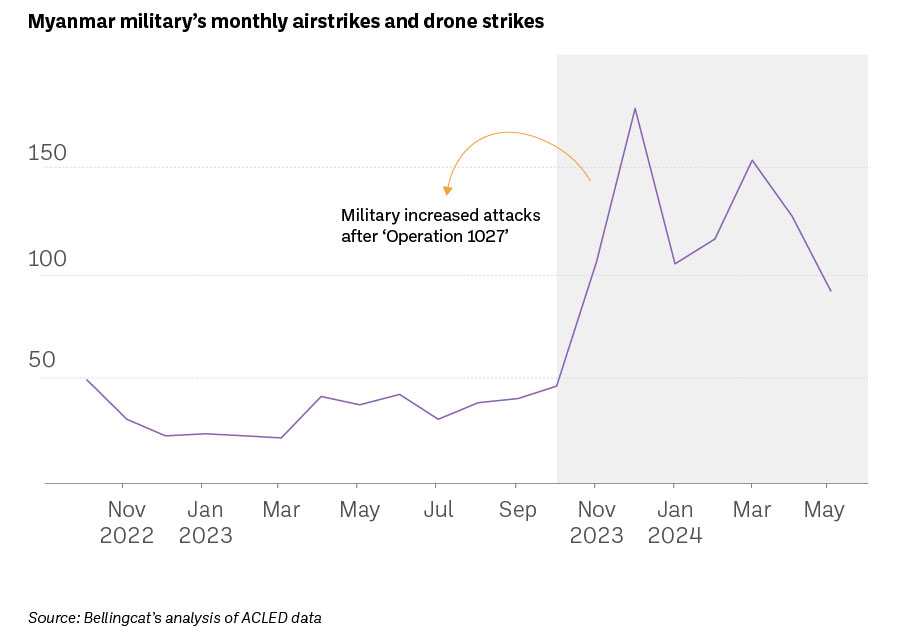

The junta, which calls itself the State Administration Council (SAC), is in a crisis and civilians in different parts of Myanmar are still bearing the brunt of the fighting between the military and armed opposition groups. In particular the military’s response to losing ground has been characterised by increased attacks against civilians. “Over the last five months, there has been a five-fold increase in airstrikes against civilians,” the UN reported in March.

Airstrikes

Bellingcat has geolocated some of the villages and towns affected by the ongoing violence that stretches across the country. Furthermore, our analysis of data compiled by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) reveals that the military has conducted nearly 100 airstrikes (including drone strikes) each month since November. ACLED’s data comes from multiple sources including media and social media–and while the data is incomplete, a broad trend can be identified. You can read further details and caveats about the data, here.

“They’re conducting a lot of strikes. Multiple strikes every single day. And so the vast majority of these airstrikes are the ones that are conducted by fixed wing planes using unguided munitions. And the typical munition, their go to, is a 500 pound bomb which they manufacture domestically…but there are other munitions in their arsenal as well,” Richard Horsey, Senior Adviser on Myanmar at Crisis Group- which monitors conflicts in different parts of the world, told Bellingcat.

“The use of drones by the military is really in its infancy. They’re playing catch up with the resistance. But they do have a lot of help from Russia,” he added.

Rakhine State

Fighting has intensified in Rakhine State where the military’s widespread human rights violations and crimes against humanity against Rohingya people led the International Court of Justice to issue an order in 2020 requiring the country to prevent genocide.

A conscription law that only applies to Myanmar citizens, enforced in February 2024, is allegedly being used to coerce young men and women into the military. Though the Rohingya, who predominantly reside in Rakhine, are denied citizenship under the 1982 Citizenship Law, reports of their forceful conscription are widespread.

“In Rakhine State, we have heard reports that displaced Rohingya youth are being offered money, food and even citizenship if they join the ranks of those who displaced them years ago. They are threatened with punishment if they refuse. And reports of forced recruitment, including child recruitment, have already proliferated among many warring parties,” said UN Human Rights Chief Volker Türk in March.

In April independent news outlet The Irrawaddy and local news outlet Western News reported that civilian houses and the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) office in the town of Buthidaung were allegedly burned down by the military using pro-military groups and Rohingya recruits. MSF confirmed its office and pharmacy were destroyed in fire on April 15. Bellingcat was not able to verify who was responsible for the attack but we were able to geolocate images of the fires in Buthidaung.

A photo shared by Western News on April 17 on Facebook that depicts smoke rising due to apparent fires was geolocated by Bellingcat to the coordinates 20.873542, 92.524165.

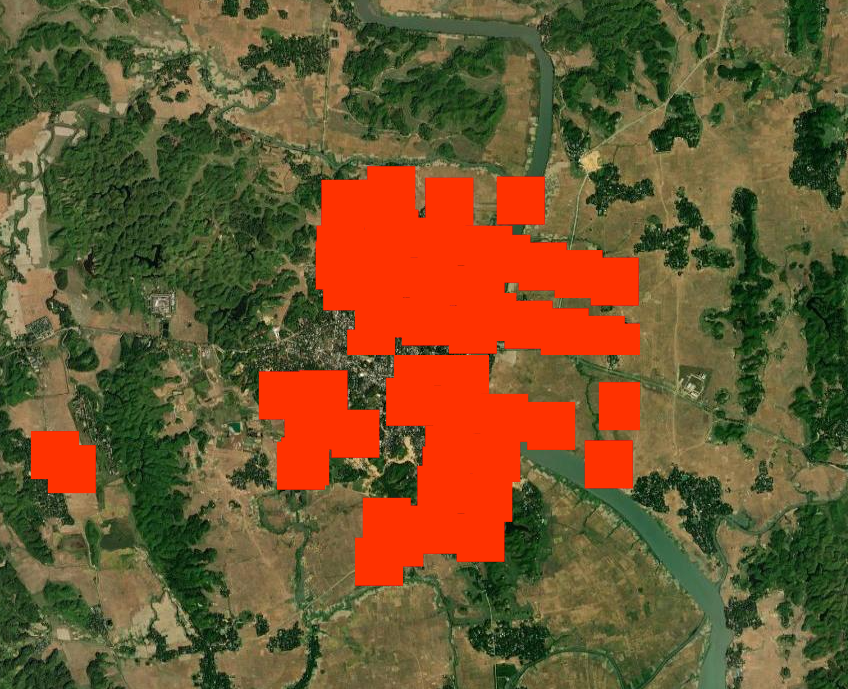

Satellite images also corroborate reports of widespread fires in Buthidaung.

“A part of the [military’s] message is you can take the town, but we’ll bomb it, and there will be no people in it because they will flee, and there will be no infrastructure left. So good luck with that town you [anti-junta groups] have got,” said Horsey.

Another neighbouring village Tha Yet Taung was reportedly hit by an airstrike on March 23 and the aftermath was geolocated by Myanmar Witness, an initiative of the Centre for Information Resilience.

However, the military is not the only one perpetrating violence against civilians in Rakhine.

Arakan Army Accused of Violence Against Rohingya

Violence continued to escalate in Buthidaung in May as the Arakan Army (AA), a powerful armed ethnic group in Rakhine, reportedly gained control of the town.

The AA has been fighting the junta since November, after breaking a year-long ceasefire agreement, for greater autonomy of the Buddhist-majority Rakhine which is also home to an estimated 600,000 Rohingya. It has now reportedly gained control of over half of the towns in the state and Rohingya activists have accused the AA of violence against their community, Reuters reports.

The UN said that hundreds of homes in Buthidaung were set alight on the night of May 17 forcing thousands to flee–though the AA has denied its role.

Bellingcat was able to detect heat signals indicative of large scale fires in Buthidaung via NASA’s Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) on May 17.

Planet imagery taken April 8 – before both military and AA reportedly attacked- and May 20 shows the scale of devastation in Buthidaung.

Strikes Across Myanmar

Although Rakhine state has been one of the epicentres of the recent escalation, many other regions in Myanmar have been subjected to airstrikes that have killed civilians and destroyed residential areas.

North: Chin State

North of Rakhine is Chin State where a hospital in Wammathu village, Mindat Township was destroyed in an alleged military airstrike on April 25. Bellingcat geolocated the hospital to the coordinates 21.493653,93.951789. This matches the geolocation first done by Myanmar Witness.

According to The Irrawaddy, four civilians were killed and 15 more injured in the hospital attack. Bellingcat could not verify these details.

East: Kayah State

To the east is Kayah or Karenni State which borders Thailand. Khit Thit Media, a local Burmese news outlet, shared pictures [Warning: Graphic Content] of an alleged military airstrike in Kone Thar village in Loikaw Township, Karenni State on April 20. According to the Facebook post, three 300 pound bombs were dropped on the village, killing six civilians and injuring 10 others. Khit Thit Media also posted footage [Warning: Graphic Content] of the aftermath which shows several destroyed houses.

Bellingcat stitched the frames of the video with a photo of the same area for a panoramic view and geolocated the incident to the coordinates 19.762245,97.159691 in Kone Thar village.

The images show significant damage to multiple structures, including some which are completely destroyed.

Zachary Abuza, professor of national security strategy at the National War College in Washington DC, told Bellingcat that the military, for the most part, uses gravity bombs.

“These are usually 250 or 500 pound bombs. There’s no precision and guidance. So they have very limited utility against dug-in guerrilla forces,” said Abuza, adding that the military’s strategy is about terrorising the civilian population into submission.

A June 2023 report by the UN Human Rights Council’s Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar said, “The Myanmar military has attempted to justify several aerial bombardments that have led to substantial loss of civilian life, on the basis that there was a military target in the vicinity of the attack.”

Armed anti-junta groups have typically used modified drones to drop bombs but these should not be compared with regime airstrikes as they are significantly smaller and more targeted, according to experts.

“The resistance is using drones that they make themselves with a small artillery ammunition or a series of munitions attached,” he said adding that the destruction capability is not the same as the regime’s which also uses modern combat aircrafts acquired from Russia. Bellingcat has previously reported on improvised drones used by rebel groups.

Religious Buildings

Civilian homes are not the only buildings being damaged and destroyed. Bellingcat’s analysis of social media posts reveals strikes on places of worship.

On April 21, airstrikes allegedly damaged a monastery in Par Hat village, Naung Cho Township in northern Shan State. Bellingcat geolocated the monastery to the coordinates 22.278979,96.540648 based on a photo uploaded by Khit Thit Media on Facebook. Another monastery destroyed in Naung Cho Township was geolocated by Myanmar Witness.

On May 1 a Buddhist temple in southern Shan State was allegedly attacked by the military, geolocated by Bellingcat to the coordinates 20.035582,97.192672 in Hsihseng Township. Khit Thit Media uploaded photos of the damaged temple complex on Facebook. This was also recently geolocated by Myanmar Witness.

Bellingcat also geolocated a damaged church to these coordinates 23.268286,94.018419 in Pyin Khon Gyi village, Kale Township in Sagaing. The images appeared on Facebook in April. Local media Mandalay Free Press reported on Facebook that the military had allegedly been raiding villages in the northern part of Kale Township since April 19, however satellite imagery of this location was not sufficient enough for Bellingcat to verify these reports.

While the military is losing ground to resistance and armed groups, Horsey said that it is unlikely they will face an immediate defeat. “The strongest anti-regime, anti-military forces are ethnic armies in the periphery of the country, whose objective is not revolution, not seizing national power or changing power at the centre. Their objective is to take control of their ethnic homelands, secure them and administer them.”

“I think a much more likely scenario is that the military will gradually be pushed out or withdrawn from the periphery, consolidating in the centre of the country…but we’re in uncharted territory and I wouldn’t like to make firm predictions,” Horsey added.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter or follow us on Instagram here, YouTube here, Facebook here, Twitter here and Mastodon here.