Investigating Information Operations in West Papua: A Digital Forensic Case Study of Cross-Platform Network Analysis

These findings were made by BBC open source investigator Benjamin Strick and Elise Thomas, a researcher with the International Cyber Policy Centre at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

A new open source investigation has analysed a well-funded and co-ordinated social media campaign aimed at distorting the truth about events in the restive Indonesian province of Papua has been operating on major social media platforms, and identified those likely to be responsible.

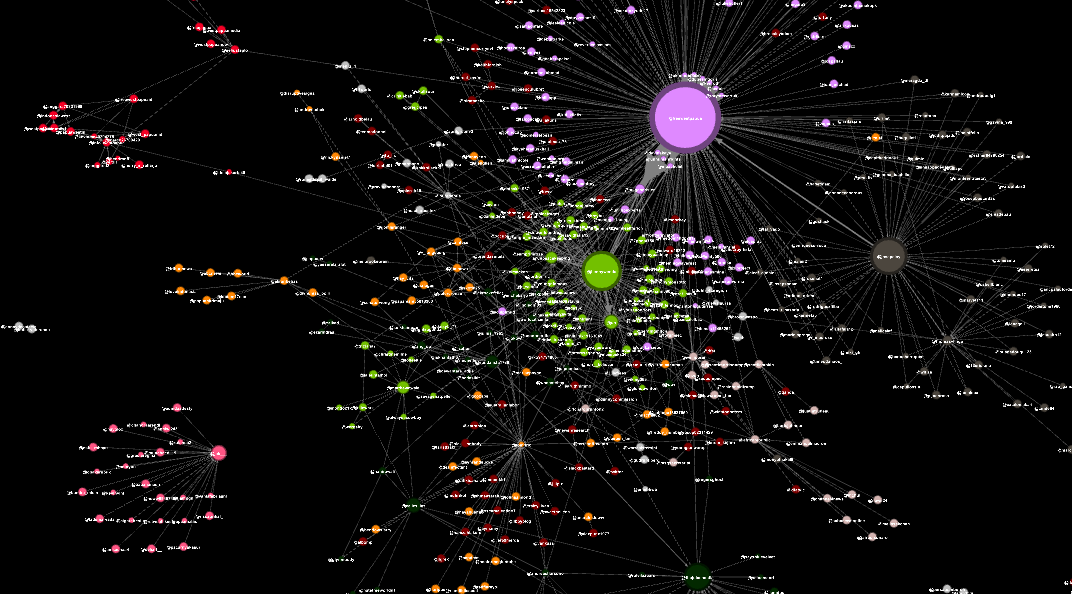

The disinformation network was initially discovered when I captured data over a five-day period in September. When I looked at the accounts posting the content, I noticed something very odd.

At first glance, it appeared as if K-pop star Kim Jennie was tweeting lots about Papua. After a closer look, however, it became clear that while the profile picture was of the pop star blowing a kiss to the camera, it was actually a fake automated account, otherwise known as a bot.

After the publication of my earlier research, Twitter took action against those accounts and suspended all of them — but then more started to pop up.

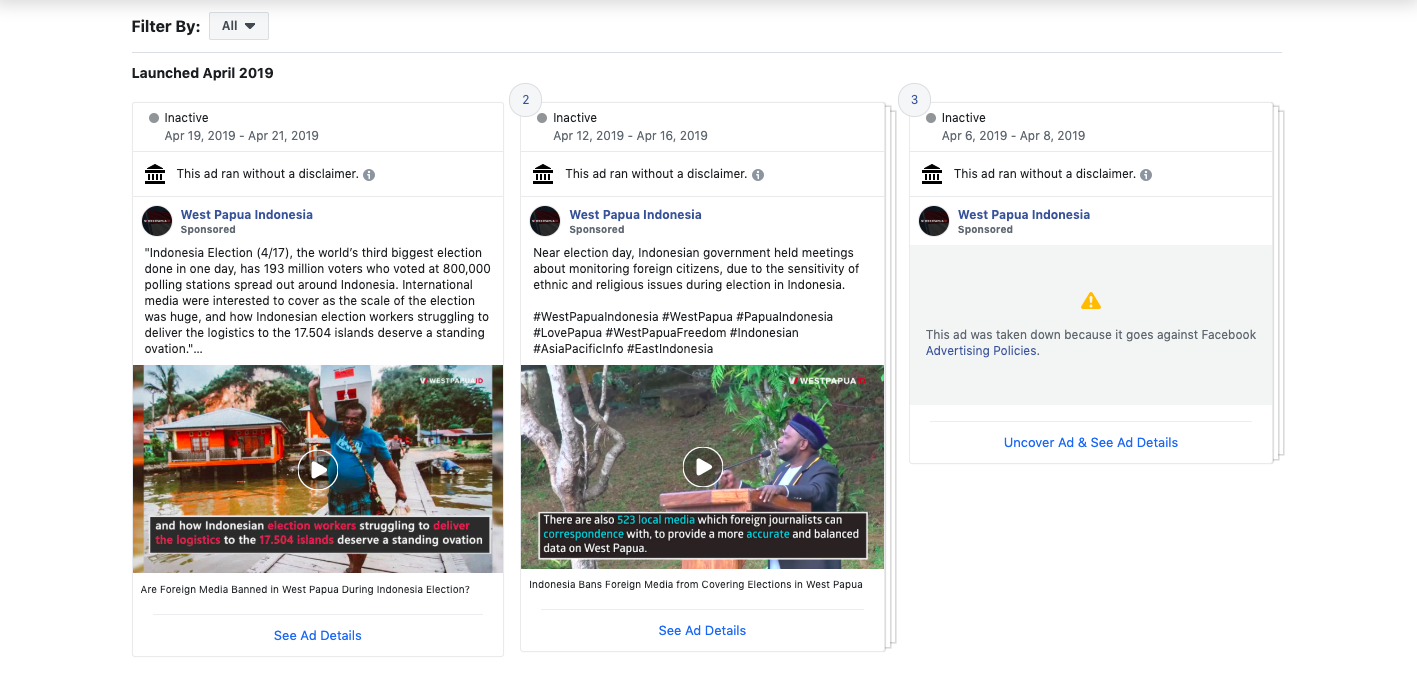

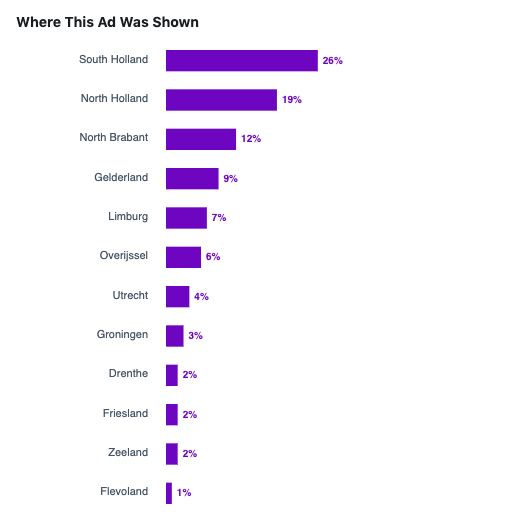

I took a further dive into the data to find out where else these accounts were linking to. I looked at the Facebook pages of the network, and found they were running propaganda advertisements in Europe, UK and the US.

On October 3rd, Facebook took action and deleted more than 100 accounts and pages, which had spent about $300,000 on ads alone. Facebook said the accounts were “involved in domestic-focused coordinated inauthentic behavior in Indonesia” and that the campaigns “created networks of accounts to mislead others about who they were and what they were doing”.

Over the past month, in a joint open source investigation with Elise Thomas, a freelance journalist and researcher with the International Cyber Policy Centre at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, we travelled far down the rabbit hole into the murky world of marketing firms, domains, shell accounts and korean pop stars to find who was behind these information campaigns.

Why Is This Important? The Danger Of Disinformation

The region of West Papua has a complex history. The former Dutch colony declared independence in 1961, only to be annexed in 1969 by Indonesia. A highly controversial vote on West Papuan independence, referred to as the Act of Free Choice, was overseen by the United Nations. Only 1025 people, reportedly selected by the Indonesian military, were allowed to vote. While the result formalised Indonesian control over the region, many have criticised this process for being deeply flawed.

In 2019, separatist groups continue to fight for independence and are making calls for a new referendum. In July, the separatist groups joined forces behind United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) leader Benny Wenda. In response, Indonesian security forces have engaged in an increasingly repressive crackdown on the region.

When the worst violence in decades erupted in Papua in August over allegations of racism and renewed calls for independence, the government blocked internet access to parts of the province, in a move they claimed was to stop hateful messages and fake news that were fuelling unrest.

Confirmed: Internet disrupted in #Papua #Indonesia to counter mass-protests amid rising calls for independence referendum; data show escalation of information controls as of Wednesday morning #Jayapura #Sorong #Timika #WestPapua

? https://t.co/uH2w2c76sG pic.twitter.com/b1rrfBvrGq

— NetBlocks.org (@netblocks) August 21, 2019

The Indonesian government has taken significant steps to restrict information about the situation in West Papua from reaching the outside world. Foreign journalists, humanitarian workers and diplomats have been restricted from entering the region and long-standing requests by the United Nations human rights officials to visit remain outstanding. The UN has called for the Indonesian government to end the excessive use of force and protect the rights of pro-independence activists to freedom of speech and access to information, including access to the internet.

Social media has become a key source of information about what’s happening in West Papua, and has become a battleground for propaganda and control over the narrative from both sides.

In a context like this in which independent media is restricted and verified information is scarce, the potential for an organised disinformation campaign such as the one we have uncovered has the potential to have a substantial impact on how the situation is perceived by the international community. This in turn could have implications for policies and decisions made by other governments, and in international forums such as the UN.

From our investigation, we know that someone was willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars and invest many months of work into this effort to influence international perceptions about the situation in West Papua in favour of the Indonesian government. The scale of the operation is an indication of how determined they were to win the battle over the international narrative, as a component of the broader conflict.

The implications of this go beyond these specific case studies, and beyond the West Papuan context, to reflect the way global social media platforms and the power of international narratives are increasingly becoming a key battleground in local conflicts.

What Did We Find?

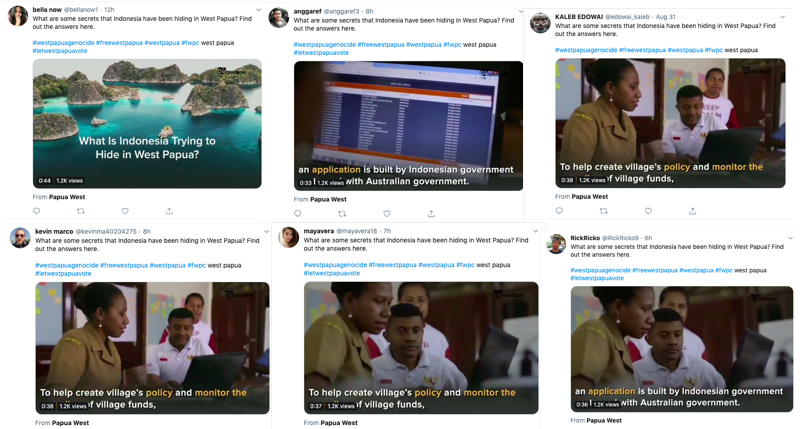

We have investigated two overlapping but independent information campaigns, conducted primarily in English, which appear to be targeting international audiences, with the goal of promoting a pro-Indonesian narrative whilst condemning pro-independence forces.

The networks operated like this: content including articles, infographics and videos was posted on the brand websites. The content was then promoted by core branded accounts on Twitter, and amplified by a network of inauthentic and/or automated accounts, as exposed in the previously published investigation.

In some cases, the content presented was factually true but significantly slanted in favour of the Indonesian government’s position. In other cases, the content itself was simply false.

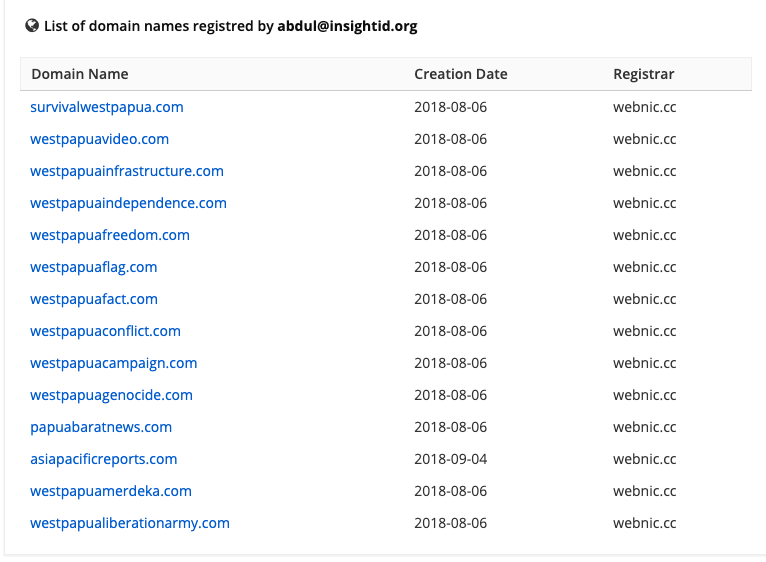

Using open source investigation techniques, we discovered that the first of the two campaigns was conducted by Jakarta-based media company InsightID. Our findings were confirmed by Facebook in a blog post on October 3rd 2019.

The company used a team of trained designers, ads analysts, English-speaking marketing specialists and IT professionals to produce high quality content in English and Indonesian promoting a pro-Indonesian narrative about the situation in West Papua, including emphasising the government’s efforts to improve Papuan infrastructure and support Papuan society, while condemning pro-independence forces as criminals and terrorists.

The company then used its networks of sites and inauthentic social media accounts to push its content out and distort the social media conversation, including hijacking search terms and hashtags, attempting to game the Google search algorithm, and flooding social media platforms with their content about West Papua.

In addition to promoting content, this campaign also engaged in targeted harassment of journalists, political leaders and pro-independence activists. They did this through the use of automated bot accounts on Twitter.

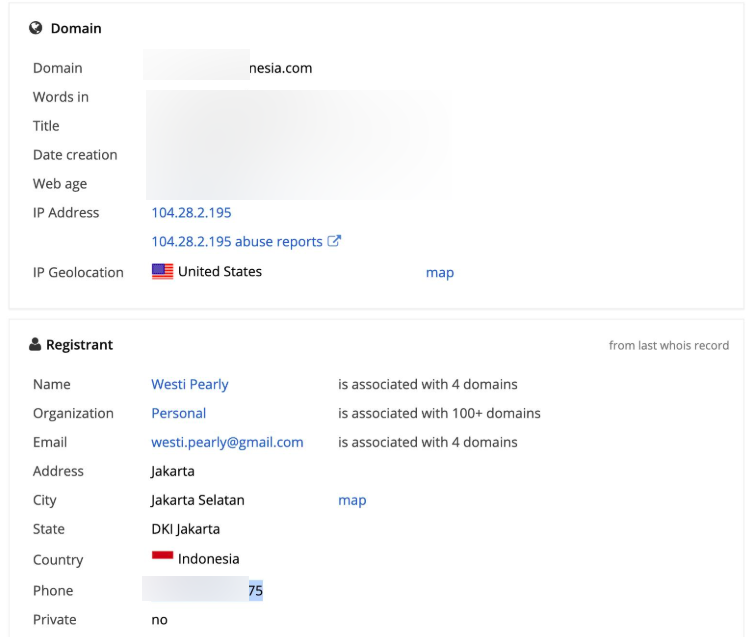

In the course of investigating the first campaign, we also uncovered a second, similar but much smaller network. We have not found conclusive evidence connecting this campaign to the operation run by InsightID.

We were able to track this campaign back to a specific individual, who has since acknowledged being responsible for some parts of the campaign to the BBC. This individual has political connections, but has said that his actions in promoting pro-Indonesian disinformation about West Papua were a personal project and not connected to his political work.

How Did We Uncover This?

All of the findings in this report have been made and are supported with open source evidence, using digital forensics to find the trails left behind by the individuals involved.

While much of the evidence has been removed by social media platforms and the campaign operators themselves, where possible we have included examples and links to archived copies of websites and social media profiles.