Analysis of Clashes at Sari Tagh in Armenia, One Year Later

On July 17, Armenia marked the one-year anniversary of the armed takeover of the Erebuni police station in the capital Yerevan. Around three dozen radical anti-government gunmen, who called themselves the Daredevils of Sassoun, seized the police patrol service regiment area in Yerevan’s southern Erebuni district on July 17, 2016, demanding the resignation of Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan and the release of Jirayr Sefilyan, the jailed leader of the Founding Parliament opposition movement.

The gunmen occupied the police base for two weeks. In the course of the standoff, three police officers – Colonel Artur Vanoyan and officers Gagik Mkrtchyan and Yuri Tepanosyan – were killed, and a number of gunmen were shot at and wounded by security forces. The group finally surrendered to police on July 31.

The two-week standoff sparked off a protest movement involving a large number of Armenian citizens, who began to participate in daily gatherings on Yerevan’s central Freedom Square and near the police base on Khorenatsi Street to express their support for the gunmen. Despite the fact that the demonstrations were largely peaceful, police detained hundreds of protesters without justifiable reasons.

The most notable and violent demonstrations took place on July 20 and July 29, during which police used excessive force against peaceful protesters and the journalists covering the demonstrations.

On the evening of July 29, 2016, Armenian police, including plainclothes officers, used disproportionate and excessive force to disperse a group of peaceful protesters who had marched through the city to Khorenatsi Street and tried to approach the seized police station through the nearby Sari Tagh neighborhood.

Riot police, after blocking the adjacent streets to block potential protester retreat routes, attacked the protesters, using special means (stun grenades, tear gas) and physical force. As a result, a large number of demonstrators and journalists sustained first and second-degree burns and fragmentation wounds. Police also hindered journalists from filming and broadcasting the events, physically attacking them and damaging their equipment.

This article will analyze video footage of the events of July 29 and attempt to reconstruct how significant incidents took place, along with documenting excessive uses of force by riot police against protesters and journalists.

How the July 29 Attack Unfolded

At around 9pm, protesters who had gathered at Freedom Square started moving through the city to Khorenatsi Street. As they approached the area, the protesters decided to change their route and approach the police base through the Sari Tagh neighbourhood, which is located on a nearby hill.

However, when the protesters reached Sari Tagh, police officers, along with plainclothes men coordinating with them, began blocking off adjacent streets and used weapons, including truncheons, stun and gas grenades, to disperse the demonstrators.

It is worth noting that the officers did not first attempt to urge the crowd to disperse or warn them adequately that they were going to use force, which they are obliged to do under the Armenian Law “On Police.” In a statement released the following day, Armenia’s police claimed that the use of special means had been justified and necessary because the protesters attempted to forcibly break through a police cordon around the occupied police station. Video footage of the events, however, does not support this allegation.

According to an official statement from Armenia’s Ministry of Health, a total of 60 people were hospitalized following the attack. Among them was 16-year-old Sayat Harutyunyan, who was injured after a grenade exploded near him. Sayat was taken to a Yerevan hospital for surgery and subsequently lost his left eye.

Sayat Harutyunyan, who lost his left eye during the July 29 incident (source)

Protester Tamara Manukyan sustained severe burns on different parts of her body as a result of police violence.

“Grenades flew upwards in spirals with a whistling sound, then they fell down. One fell on my foot, and by the time I understood that it had hit me I was already in flames. I thought I would be able to run away from the grenade when I heard the explosion, but I was already burning and could not move,” Manukyan later told a group of monitors sent to Yerevan by the International Partnership for Human Rights to look into the events.

Graphic images showing Tamara’s injuries can be seen here.

Other interviewees told the monitors that they had witnessed police officers storming the properties of Sari Tagh residents, carrying out searches and beating some inhabitants. One Sari Tagh resident, who wished to remain anonymous for security reasons, told the monitors:

“When the police started throwing stun grenades I ran with other protesters, almost 12 people, and entered the first house we came to. The police threw a grenade on the house and the fence caught fire. Then a second grenade was thrown into the house and exploded inside. Many people were injured, everyone was panicking. After 10 or 15 minutes the owners asked everyone to move to the next house and go into the basement as police officers were entering houses and taking people. I and several other protesters stayed in a basement for around an hour.”

In a video published by CivilNet, it is clearly visible that police officers are throwing grenades in the direction of residential houses, where there were no protesters, let alone violent ones, in sight.

The same video also shows a woman treating a fragmentation wound on a young boy’s neck. “[The grenade] exploded right under my feet, just a meter away. I was standing [by our house] and the grenade fell on our stairs,” the boy says.

Types of Grenades Used

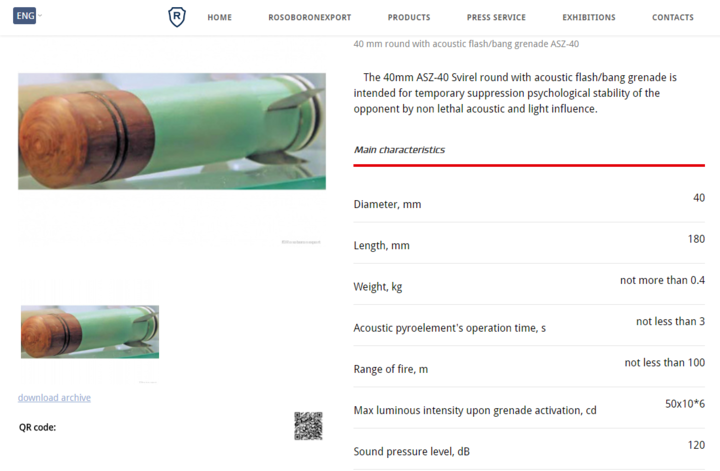

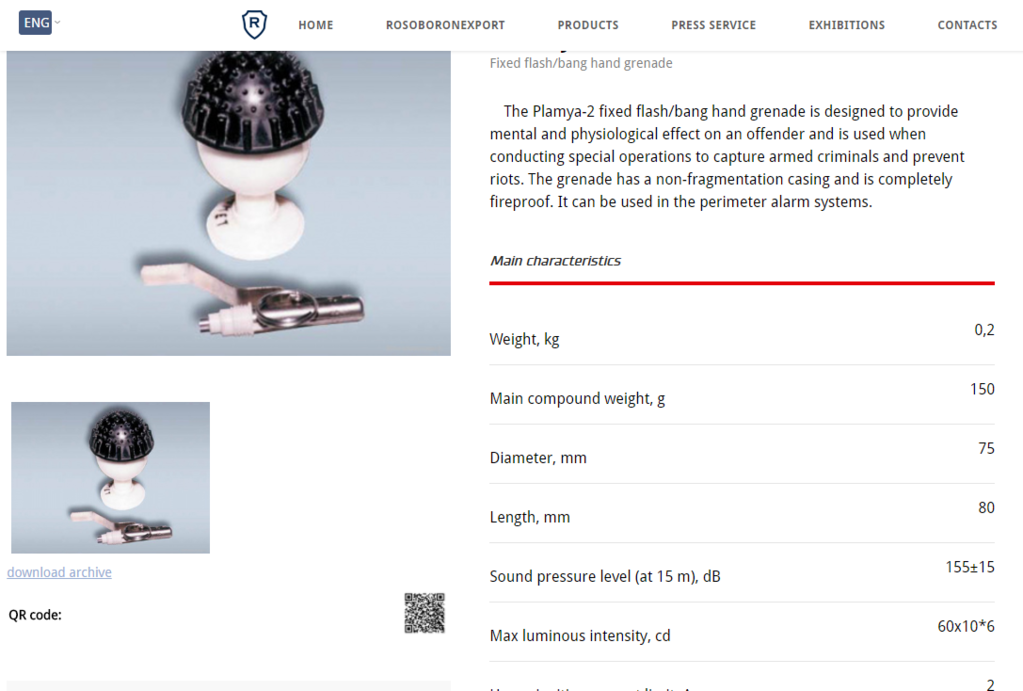

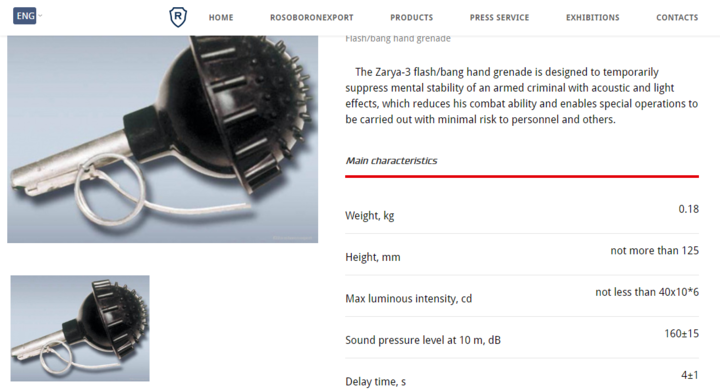

According to Health Ministry-approved safety standards, these types of grenades – Zarya-3, Fakel-S, Drofa, Plamya-M and 40mm ASZ-40 Svirel flash/bang bombs – should not be exploded at a distance of at least 2.5 meters from a person. Most of the video footage, however, shows police throwing these grenades directly into the crowds.

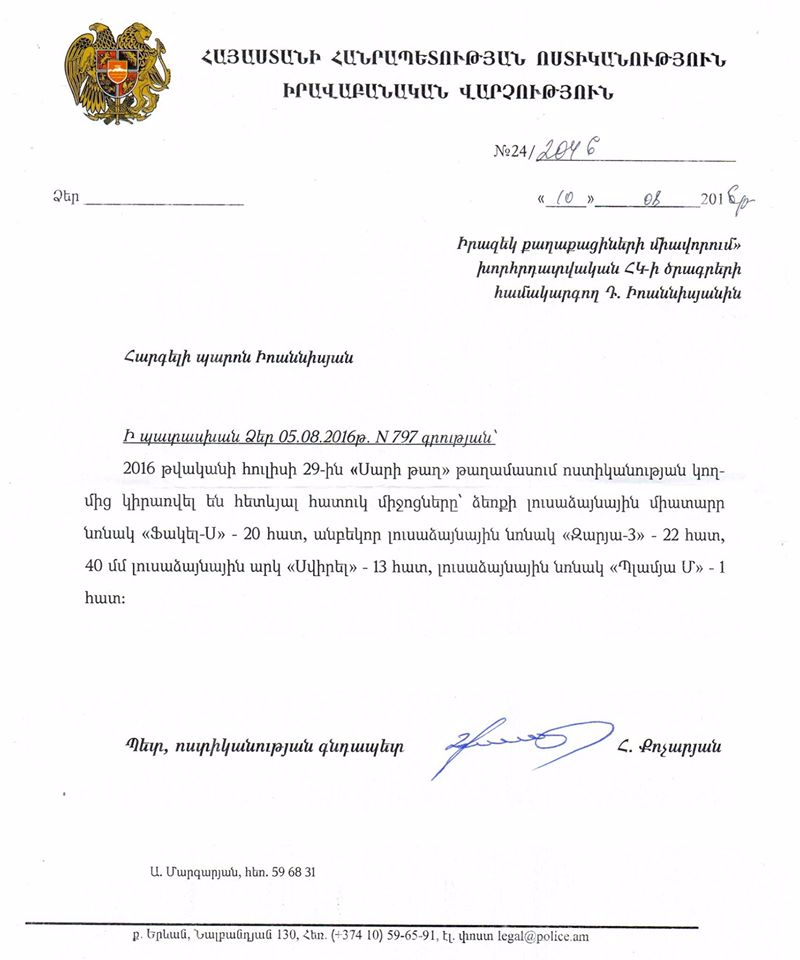

The police described which grenades were used during the protest in a response to the Union of Informed Citizens.

Police response to the Union of Concerned Citizens, describing which grenades were used during the protest (source)

These weapons are all Russian or Soviet in origin, with the majority sold by the Russian firm Rosoboronexport.

40mm ASZ-40 Svirel round on the Rosoboronexport site

Plamya-2 on the Rosoboronexport site

Zarya-3 on the Rosoboronexport site

Drofa, by Vitaly V. Kuzmin [CC BY-SA 4.0 or CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Fakel-S (source)

Injuries to Journalists

At least 20 journalists and cameramen were injured during the police crackdown. Some of them subsequently claimed that they had been chased and beaten up by plainclothes officers with truncheons. Marut Vanyan, a cameraman with Lragir.am, told RFE/RL’s (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty) Armenian Service (Azatutyun.am) that a large group of men “continuously hit me. I protected my face with a backpack. But they hit me in the hands and legs.”

A1+ TV station reporter Robert Ananyan sustained leg and hand injuries from fragments of stun grenades. He told Human Rights Watch (HRW) that, while live streaming from the Sari Tagh demonstration, he saw high-ranking police officers warning protest leaders to disperse within five minutes. The officers, however, did not make any public announcement to the other protesters and about 15 minutes later, they told journalists to step aside as something was about to happen:

“This was the only warning we got, and within two minutes, stun grenades started exploding. There were so many of them that you could not escape.”

A number of other reporters, including 1in.am cameraman David Harutyunyan, 1in.am journalist Mariam Grigoryan, and freelance journalist Anushavan Shahnazaryan, have told HRW virtually the same story.

“Police started beating batons on their shields and moved forward on demonstrators; also throwing stun grenades. They would take the safety pin out and throw the grenade right away toward the protesters. The grenades caused shrapnel and that’s how I got wounded. I was still filming as the attack started, but was able to move for only few meters when shrapnel hit me on my right leg,” Harutyunyan said.

He also added that as he continued filming, several men in civilian clothes began chasing him and proceeded to beat him with wooden clubs.

Mariam Grigoryan, in turn, said:

“[Police] started throwing stun grenades at the public before they moved on the crowd…. Soon they threw them toward the area where the journalists were gathered. One of the grenades exploded in front of me. I could not see or hear anything; I thought I was dead. Then I realized that I could move my hands and only had difficulty moving my leg, and I realized that I was alive.”

Three RFE/RL Armenian Service journalists – Karlen Aslanyan, Hovannes Movsisyan, and Garik Harutiunyan – were attacked by plainclothes men armed with sticks and metal bars. According to the journalists, the men “were clearly aware that they are assaulting reporters.”

(source)

(source)

The Aftermath

A few days after the Sari Tagh events, Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan publicly apologized to the journalists, urging them to forget about those incidents because he was “really sure” that they would not be happening again.

National police chief Vladimir Gasparyan, for his part, ordered his subordinates to identify and locate “the civilians” who had assaulted the journalists. Law enforcement authorities have since identified nine men – though they have refused to publicly reveal the names – responsible for the violence. However, they have pressed criminal charges only against two of them; the others have gotten away with only fines.

In August 2016, nearly two dozen police officers, among them Yerevan police chief Ashot Karapetyan, were subjected to disciplinary action for their poor handling of the events and failing to prevent the violence against protesters and journalists. Karapetyan was subsequently sacked from his position.

Although a year has passed since the violent events, no police officer has been prosecuted over the attacks on either peaceful protesters or journalists. A number of protest participants, on the other hand, are currently on trial for resisting police and several have already been sentenced to prison terms.