The OPCW Douma Leaks Part 2: We Need To Talk About Henderson

Executive Summary

- Henderson was an employee of the OPCW, but the organisation clearly did not consider him to be part of the FFM.

- Henderson delivered his report outside of protocol with less than a day before the final FFM report was published.

- Three independent engineering studies commissioned by the FFM contradict Henderson’s findings.

- Henderson’s report is fundamentally flawed by the assumption that these cylinders could not have fallen from an altitude of less than 500 meters.

- The methodology that Henderson employed for this report was not adequate for this task.

In our first article in this series, we examined the claims of “Alex” and the documents released by WikiLeaks. In this article, we will look at a report by a self-described “engineering sub-team” of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), headed by Ian Henderson.

Henderson’s report examines the impact of what appear to be two chlorine cylinders associated with a chemical attack in Douma on April 7, 2018. One of these cylinders was found on a balcony at Location 2 and one in a bedroom at Location 4. Henderson’s report concluded that it is more likely the cylinders were manually placed than dropped from altitude. Although Henderson’s report claims to have used the same data as the Fact Finding Mission (FFM) of the OPCW, it must be emphasised that three independent engineering studies commissioned by the FFM contradict Henderson’s findings.

Henderson’s report was first leaked on May 13, 2019, however, the Russian Federation appears to have had access to it well before this date. On April 26, 2019, the permanent representative of the Russian Federation to the OPCW sent a critique of the final FFM report to the OPCW, sections of which were remarkably similar to Henderson’s report. The Director-General of the OPCW said that he learned this report may have been leaked as early as March 2019.

Taking a closer look at Henderson’s report helps to explain why it is not consistent with the FFM’s conclusions. It is evident that Henderson’s methodology was fundamentally flawed, and that a major assumption was made about the altitude from which these cylinders could have fallen. There also appear to be several errors or inaccuracies in other aspects of the report.

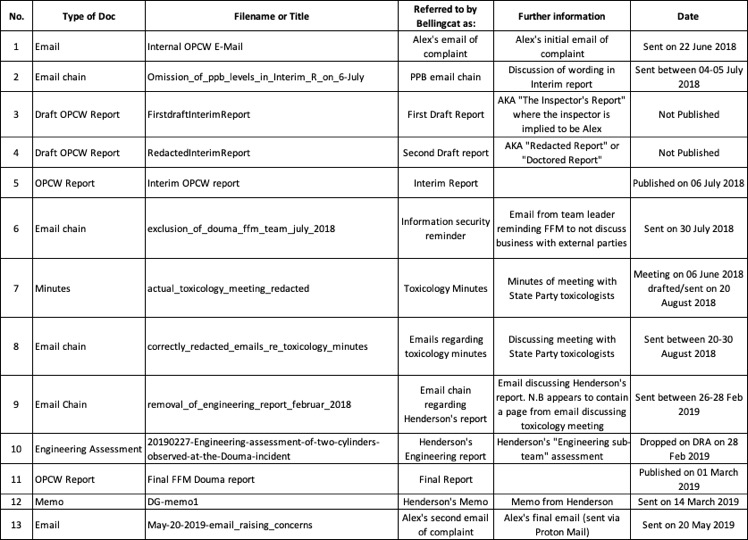

As with Part 1 of this series, we have included a list of the documents leaked by WikiLeaks in an attempt to make the timeline of this event more transparent.

- Alex’s initial email of complaint

- PPB email chain

- First draft report

- Second draft report

- Interim OPCW report

- Information security reminder

- Toxicology minutes

- Emails regarding toxicology minutes

- Email chain regarding Henderson’s report

- Henderson’s engineering report

- Final report

- Henderson’s memo

- Alex’s second email of complaint email

Who Is Henderson?

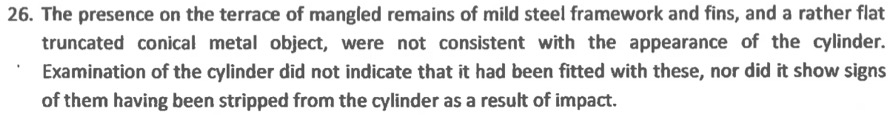

Ian Henderson does indeed seem to have been a real employee of the OPCW, and the leaked documents do indicate that he deployed to Douma in support of the FFM. A memo sent by Henderson, dated March 14, 2019, appears to be an email from Henderson and describes his work. He stated he had visited the scene in Douma, and afterward spent five weeks in charge of the OPCW control post inside Syria.

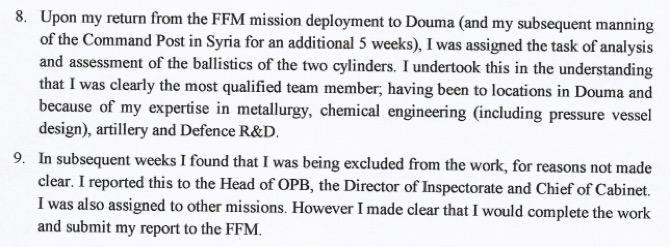

On return from Douma, Henderson claims to have been assigned the task of “analysis and assessment of the ballistics of the two cylinders”. After this point, Henderson claims to have been “excluded from the work”, presumably by the FFM team, but that he chose to continue working on his engineering report.

Extract from Henderson’s memo from 14th March 2019, claiming to have been excluded by the FFM “core team”.

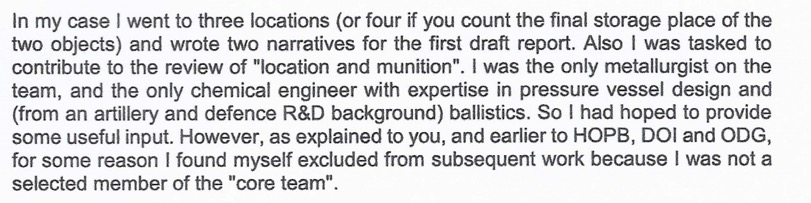

However, in an earlier email chain regarding Henderson’s report, dated from February 26, 2019, Henderson only mentions that he was “tasked to contribute to the review of ‘location and munition’”. He also explicitly states that he has been excluded from the work because he is not a member of what he refers to as the “‘core team’”.

Extract from Henderson’s email dated 26th Feb 2019, from an email chain regarding Henderson’s report.

In this earlier email from February, Henderson does not appear to mention being explicitly tasked to create this report. Without further information it is impossible to identify who told Henderson to do exactly what task, or why. However, he does claim to have received some form of authorisation from the Director of Inspectorate (DoI) in order to gain access to engineering computational tools to continue his work.

As such, it seems Henderson did have approval to do this work at some level of the OPCW. Without a detailed knowledge of the inner structure of the OPCW, it is not possible to assess whether this authority was sufficient for the work he was undertaking. As we will see, it seems at least one senior member of the OPCW was shocked when they found out Henderson had created this report.

Henderson’s Status As A Member Of The FFM

The main reason why Henderson may have been “excluded from the work” of the FFM is that the OPCW did not regard him as being part of the FFM team itself, and because the FFM is regarded as a highly confidential mission. Although he deployed in support of the FFM in Douma and was clearly involved in gathering evidence, this does not appear to qualify him as actually being a part of the FFM in the eyes of the OPCW.

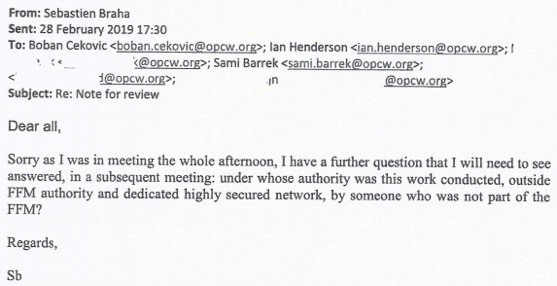

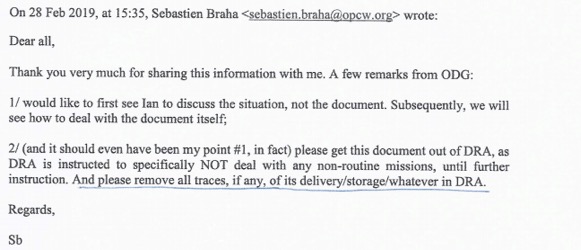

The OPCW has previously denied Henderson was in the FFM, explaining that he “was tasked with temporarily assisting the FFM with information collection at some sites in Douma”. WikiLeaks also leaked an internal email from the Sebastien Braha, Chief of Cabinet of the Director General of the OPCW, questioning why Henderson had carried out this work “outside FFM authority… by someone who was not part of the FFM?”. This email was clearly never intended to be public, and Braha had no reason to obscure Henderson’s role.

Extract from email dated 28 Feb 2019, from an email chain regarding Henderson’s report.

Despite Henderson’s distinction between the “FFM team members” and the “core team” and Alex’s complaints, it is clear that as an institution, the OPCW only regarded what Henderson describes as the “core team” as being the FFM. This did not include Henderson.

When Did Henderson Submit This Work?

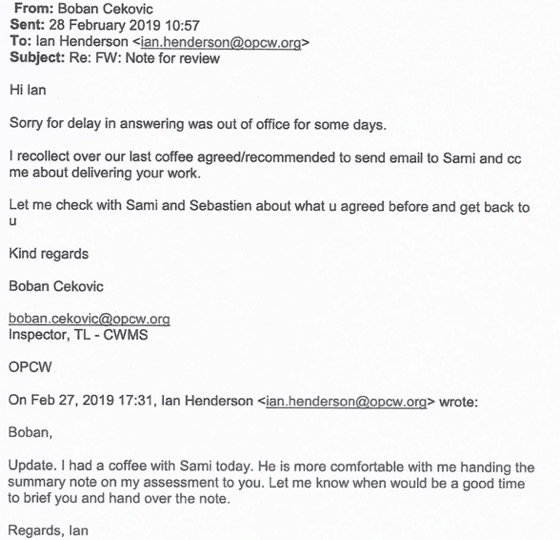

Henderson claims to have first attempted to submit his document “starting from 15 February 2019”, however, at the time of writing the earliest evidence we have of Henderson attempting to deliver his report appears to have been on February 27, 2019, two days before the final report was due to be published. The person he is emailing, Boban Cekovic, appears to have received contradictory information about how this report should be handled and offers to check.

Emails between Cekovic and Henderson, from an email chain regarding Henderson’s report.

(The pdF of the emails above, which were leaked by WikiLeaks, also, rather bizarrely, contain an email from a completely unrelated email regarding the minutes of a meeting with toxicologists. This does not appear to be part of the email chain discussing Henderson’s report.)

Henderson then informed Cekovic that he had “dropped” the report at the DRA. The DRA is referred to in multiple OPCW documents as “Documents, Registration and Archiving” and appears to be some kind of service that carries out these functions. Henderson claims he dropped off the document on February 28, 2019 at a quarter to three in the afternoon, the day before the final FFM report was due to be published. This would not have given the FFM or other stakeholders sufficient time to assess it before the publication of the final FFM report on March 1. As we have seen, Henderson’s report appears to have come as a surprise to others within the OPCW.

Once brought to his attention, Braha asked why Henderson had placed such a sensitive report in the DRA and asked for it to be removed. Although some have attempted to portray this as a cover-up, Braha’s motivations seem clear: the Douma investigation is a “non-routine mission”, and the DRA was not supposed to hold those kinds of documents.

Email from Mr Braha dated February 28, 2019, from an email chain regarding Henderson’s report.

Henderson’s Report

So far, the only documentation which has been published regarding the findings of Henderson’s “engineering sub-team” has been this report, which is a summary document: it does not include the simulation or large amounts of the data associated with the simulation. Indeed, even the technical drawings in both versions of his leaked report are too low quality to read properly. This makes it very difficult to assess the simulation itself.

However, we can look at the data and information that Henderson fed into this simulation and compare it against what we know about the Douma attack and previous examples of chemical weapons usage in Syria. Once we do this, it becomes clear that Henderson has based this entire simulation on one major assumption and several errors. Although his simulation may be accurate with the data provided, a simulation based on an assumption is unlikely to return reliable results.

The major assumption which potentially influences Henderson’s analysis was that the cylinders could not have fallen from an altitude of less than 500m. Although helicopters do usually operate at a higher altitude in Syria, it is entirely possible this helicopter was deliberately flying lower than 500m.

Although a low-flying helicopter puts it within range of small arms, it can also make it more difficult to target, especially if it were deployed at night, as was the case in Douma. There are circumstances which may have led to this helicopter flying below 500m, and Henderson’s decision to exclude that as a possibility is based not on evidence, but assumption.

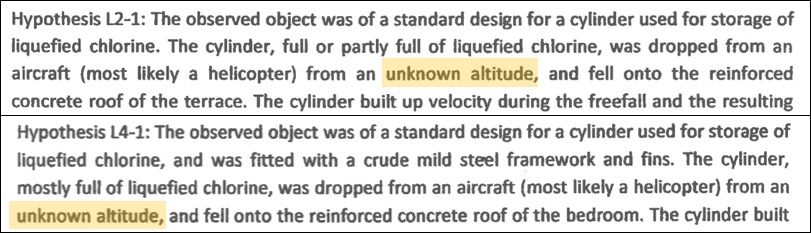

Indeed, Henderson explicitly says in the hypotheses section of the report that these cylinders should be considered to have fallen from an “unknown altitude”. By arbitrarily setting the minimum altitude to 500 meters for his simulation, Henderson is not only introducing a fundamental assumption into his analysis, he is not even testing his stated hypothesis in the simulation.

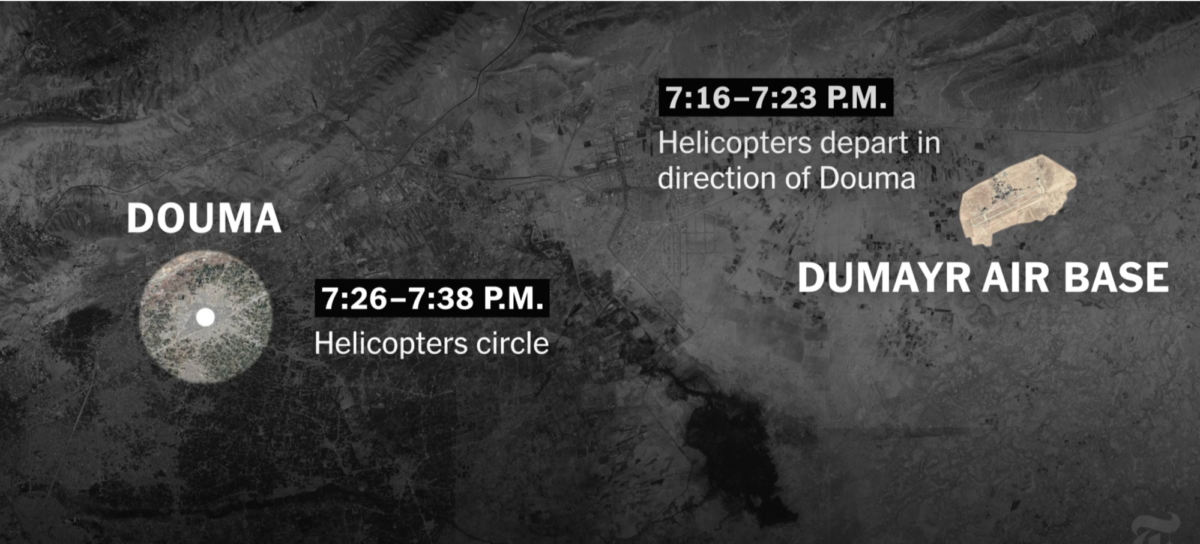

Due to a network of plane-spotters who operate in the ground in Syria, we even know there were reports of two Mi-8 Hip helicopters taking off from Dumayr airbase, followed by two of the same kind of helicopters above Douma at the rough time this attack took place.

Graphic from the New York Times Visual Investigations Team investigation into Douma

Analysis Of Location 2

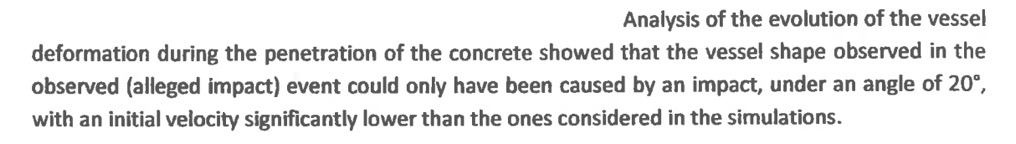

Henderson’s assessment about Location 2 is flawed from the outset by the assumed minimum altitude at which the cylinder dropped. Bizarrely, the report does in fact state it was possible to simulate an impact that was consistent with Location 2, but that the velocity was significantly lower than cylinders dropped from 500 m or higher.

Extract from Henderson’s report

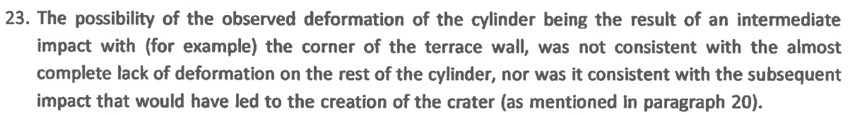

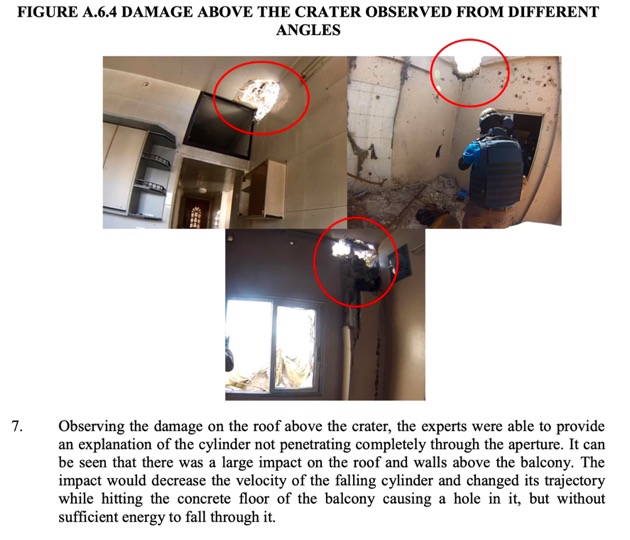

The report also appears to dismiss other circumstances that could have affected the impact. For example, the report does consider the possibility of an “intermediate impact” with the corner of the terrace wall. However, this scenario was dismissed due to lack of observed damage on the rest of the cylinder, as well as the perception that this intermediate impact would not have been consistent with the secondary impact that created the crater. It is not made clear in the report whether Henderson actually simulated this scenario or not.

Extract from Henderson’s report

It should be noted that the final FFM report did simulate this scenario and the damage to the cylinder did appear to be consistent with an intermediate impact.

Extract from final FFM report

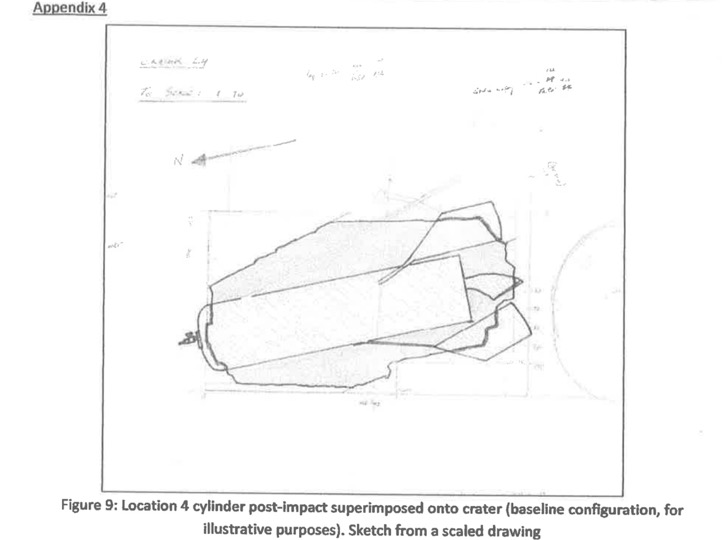

Henderson also dismisses the idea that the cylinder was fitted with the framework found on the roof.

Extract from Henderson’s report

However, Forensic Architecture recreated this framework and identified that the mild steel framework not only fits onto the munition perfectly, but is also almost identical to that seen at Location 4, and indeed many other examples of chlorine munitions used in Syria. This framework being attached to the cylinder was entirely consistent with the hypothesise that Henderson was supposedly testing, yet he chose to ignore it.

Forensic Architecture recreation of the framework.

Henderson’s statement that the cylinder did not appear to have been fitted with the framework is also odd: no example we have identified of this kind of framework appears to be bolted, welded or otherwise physically attached to the cylinder. Rather, the framework is held on by the tension of the securing bands, leaving no obvious trace on the cylinder itself. Henderson’s decision to simply discount this framework is not supported by what we know about this kind of munition.

Henderson also states that the crater on the balcony at Location 2 is “more consistent with that expected as a result of blast/energetics (for example from a HE mortar or rocket artillery round)”. In support of this he mentions several points: the way the rebar in the roof has deformed, a crater of similar appearance on a roof close to the balcony (which he does not confirm was created by a blast), an “unusually elevated, but possible” fragmentation pattern, indications of concrete spalling and black scorching underneath the crater.

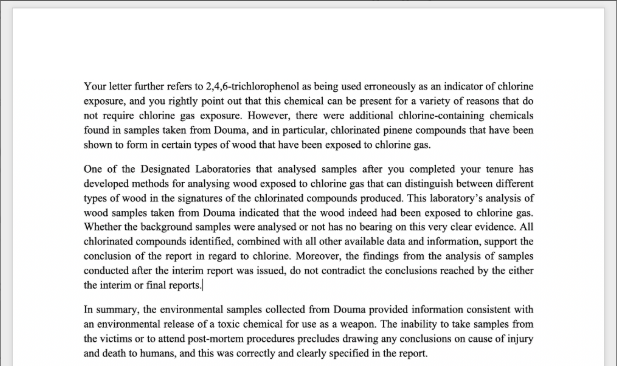

The final FFM report directly disagrees with these findings. They also considered the possibility that the crater was a result of an explosive device, but concluded that it was “unlikely given the absence of primary and secondary fragmentation characteristic of an explosion”. We also know that the scorching under the crater was likely not from an explosion: the final FFM report includes an interview where a witness states that the black scorching underneath the crater was as a result of someone lighting a fire in the room in a crude attempt to decontaminate it.

Analysis Of Location 4

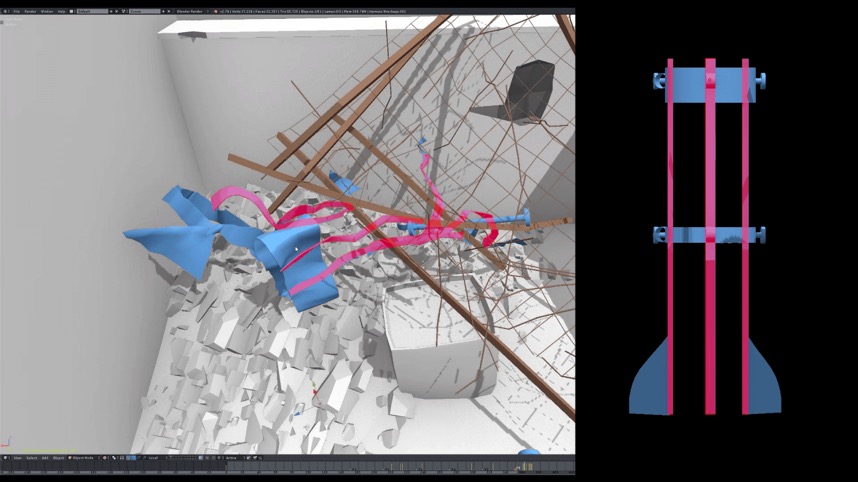

Henderson included a graphic in his report that showed the cylinder at Location 4 overlaid on the hole in the roof. Although this was included for “illustrative purposes”, the manner in which it has been placed, with the front of the cylinder jutting out over the hole, appears to support Henderson’s claims that this cylinder could not have passed through this hole with the “valve still intact… and the fins deformed in the manner observed”.

Extract from final FFM report

Bellingcat and Forensic Architecture worked together to re-create the cylinders based on dimensions found in various OPCW reports. The final FFM report noted the height of both cylinders found at Douma to be 1.4 m. They also noted the width of the cylinder at location to be 0.35 m. Additionally, the final FFM report reported the dimensions of the hole in the roof to be 1.66 x 1.05 m. We assessed these measurements and noticed that the cylinder used in the image above appears to be approximately 8 cm too long, a notable difference in the stated measurements.

It is also notable that Henderson used an image of the cylinder post-deformation to “illustrate” his work, when it is much more informative to compare the pre-deformed cylinder to the hole. In short, this “illustration” is unsuited to show the cylinder in relation to the hole. Its format in the report is potentially misleading.

We can also call into question Henderson’s statement that “The observed deformation… were clearly consistent with a cylinder having impacted in a flat configuration on a horizontal surface, and not that of a cylinder having penetrated through a crater.”

Images of the cylinders with their framework clearly show that the fins have been bent in a manner that suggest it has passed through a gap, while at least one of the securing bands has ruptured in a way that indicates it was pulled apart, which could have been the case if the cylinder had passed through a hole in the roof.

Bottom: Location 4. Note the manner in which the rear-most securing band has ruptured and deformed. The top image is an example of a virtually identical munition found in Aleppo in 2017.

Although Henderson noticed the heavy corrosion on the cylinder, he states that this corrosion would “most likely not have degraded to such an extent in the case of it being inside the bedroom” and that it seem unlikely that such an “old, rusty, already damaged cylinder” would be deployed from an aircraft.

The implication of this is that the cylinder has been recycled from another attack, indicating a “false flag”. However, in Part 1 of this series we demonstrated without doubt that the framework of this cylinder was initially clean and un-corroded. The rapid corrosion was almost certainly as a result of the metal having come into contact with chlorine gas, which results in rapid corrosion.

1: Still from video by Forensic Architecture, 2: Still from video by Forensic Architecture, 3: Image taken on 8th or 9th April, 4: image from Russian news report aired on 26th April, 5: image of cylinder in FFM final report, 6: image of cylinder in Final FFM report after tagging, indicating it was taken on the 3rd June 2018.

The Methodology

The report’s methodology describes how an attempt was made to create two clear opposing hypotheses which were then tested against each other. The problem with this methodology is that Henderson didn’t actually apply it properly.

We have already seen that Henderson did not even simulate his stated hypotheses. Instead, he arbitrarily set the minimum altitude from which these cylinders could have fallen at 500 m. It is also evident that although Henderson has examined the impact of the cylinders in detail, he does not appear to make any attempt to examine the actual likelihood of the cylinders having been placed manually.

Indeed, the report provides no actual information directly supporting the hypothesis that the cylinders were been placed manually: it only provides information that might detract from the likelihood of the cylinders falling from height. Comparing two scenarios and deciding one is unlikely does not necessarily make the other more likely.

Needless to say, this is a major oversight. The reality is that the circumstances which would lead to the cylinders having been placed manually (thereby implying the attack was faked), are extremely complex. Any analysis of how the cylinders reached their positions must take this into account.

As such, we decided to complete Henderson’s analysis for him. Part 3 of this series will examine all we know about this event and identify what exactly it would take for the Douma attack to have been faked.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Henderson’s report is flawed from the outset by a major assumption which undermines the validity of his simulation. Trust in his report’s findings are not reinforced by the implication that it was written without proper authorisation, by someone the OPCW did not regard as being part of the FFM. Henderson then attempted to submit this report, which appears to have been unexpected, outside of protocol, and without time for anyone to reasonably review it. This document then appears to have been leaked shortly afterwards.

Henderson’s assumption that a helicopter could not have operated under 500m is a major assumption upon which he bases his simulation. There is no direct evidence about the height that these cylinders were dropped, yet Henderson arbitrarily decided it could not have been under 500m.

Despite Henderson including a seemingly rational methodology, it is completely inadequate for this task. In this situation, the question of how the cylinders reached their locations cannot be rid of context — attempting to do so is misleading. At no point does Henderson consider in detail what it would mean for the cylinders to have been placed manually. Indeed he does not touch on that hypothesis until the conclusion, where he decides that it is in fact the most likely scenario.

Finally, there is the elephant in the room. The fact the FFM carried out three independent engineering analyses, by three independent teams, all of which contradict Henderson’s findings.