Roadblocks in Turkey’s New Southeast Strategy: An Analysis

With the resurgence of direct military conflict with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 2015 and in the wake of the 2016 coup attempt, Turkey began to reinstall and reinvigorate the invasive security apparatus it constructed during the 1980s.

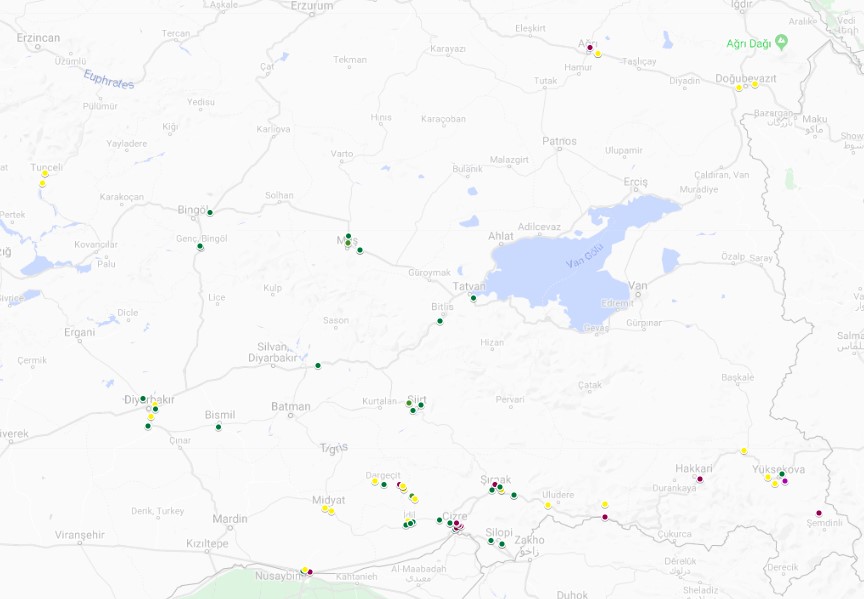

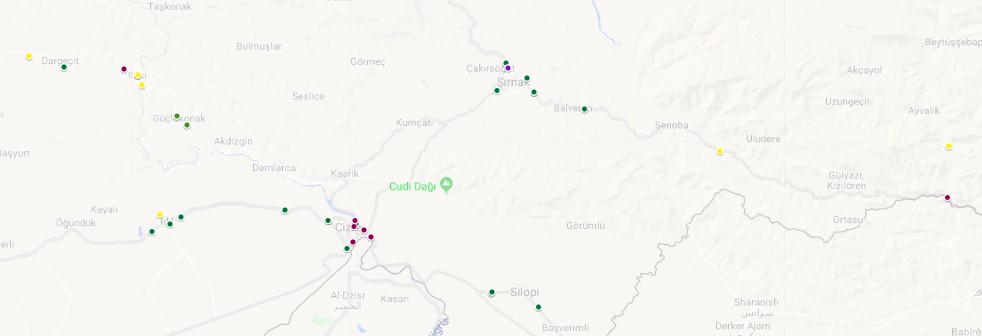

This report uses satellite imagery to track the development of 73 checkpoints across southeast Turkey, showing the evolution of the system in the aftermath of the failed ceasefire with the PKK.

Crucially, for most of the checkpoints observed, more permanent structures were developed after the end of major military operations in the area.

This report’s checkpoint map shows the shift from informal roadblocks in 2015 and early 2016 to more permanent and fortified checkpoints in both urban and rural settings.

The checkpoints are evidence of what has been described by The New Turkey as Turkey’s new strategy to employ “non-stop anti-terrorist security and military operations, not only in city centers where PKK-affiliated persons might live, but also in rural areas.”

Turkey’s new security strategy aims to penetrate rural society in the southeast by installing checkpoint structures, bolstering the village guard system, appropriating land for new security installations, blurring the lines between civil and military forces, and initiating a political crackdown to cement a long-term military presence.

This report shows that kinetic military operations are but a small part of a larger and more permanent security strategy.

Methodology And Map Of Checkpoints

Key:

Red = 2015 to June 2016 checkpoint appearance

Green = July 2016 to December 2016 checkpoint appearance

Yellow = January 2017 to 2018 checkpoint appearance

Link to map

This map shows checkpoints visible in the most recently available satellite imagery on Google Earth Pro and Terraserver. Every major highway in southeastern Turkey was examined for checkpoints using imagery from early 2017 or later. Checkpoints that were in place prior to 2017 but then removed are not recorded.

Once a checkpoint was found, earlier satellite imagery was examined to determine approximately when it was established. Unfortunately, there are gaps in imagery of up to one year for some areas, making it difficult to know exactly when certain structures were put in place between 2015 and 2016.

Satellite imagery from after 2016 is also unavailable for many parts of the above map, particularly in the Hakkari region. It should be noted that the map only includes current checkpoints that are clearly identifiable by satellite imagery and does not reflect the more informal checkpoints erected in villages or those in districts where updated satellite imagery is unavailable.

Checkpoints outline the various intersecting highways in the southeast, surround big cities, and cluster around some high-conflict areas, as well as military and jandarma (the Turkish armed forces’ police and border control) bases. Checkpoints are visually identifiable by: Roadblocks, blast walls, lines of cars, diverted roads, military vehicles, and structure type. These identifying features usually change over time as the checkpoint evolves. Videos, local news reports, and land appropriation documents corroborate the existence of many of the checkpoints included on this map.

This report will begin with a brief overview of the renewed conflict to contextualize when and why checkpoints were built and updated. After detailing the evolution of checkpoints, it will then examine the village guard system and land appropriations to provide an analysis of the new security apparatus constructed following the conclusion of major military operations in the southeast. The report will conclude with case studies of checkpoints in both cities and villages.

The 2015 Conflict In Southeast Turkey

In 2013, following a series of secret negotiations, the government struck a deal for a ceasefire with Abdullah Öcalan, the founder and symbolic leader of the PKK. The agreement was supposed to mark the end of a conflict that has been raging since the PKK took up arms in 1984 and that had claimed more than 40,000 lives by 2015.

The July 2015 massacre in Suruç was the beginning of the end for the ceasefire. ISIL killed 32 people and wounded more than 100 in a suicide bomb attack on a cultural center in the Turkish town near the border with Syria. In response, two days later PKK militants killed two Turkish police officers whom they accused of “collaborating with Daesh.”

On the same day, the Turkish government launched Operation Yalçın Nane in Iraq and Syria. Many PKK members and sympathizers considered the operation a breach of the ceasefire.

The new operation was contentious not only because it targeted the PKK, but also due to the increasing relevance of the Syrian Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its armed affiliate, the People’s Protection Units (YPG). The PKK’s inherent linkage to the PYD and the YPG reinvigorated the perceived threat of transnational Kurdish affiliation and territorial sovereignty.

Furthermore, the ceasefire depended on the disarmament of the PKK, but their involvement in operations against ISIS in neighboring Iraq and Syria made this increasingly unlikely.

PKK retribution attacks in response to Suruç were the first in a chain of sporadic attacks across the southeast. The immediate targets were primarily Turkish police officers, jandarma, and soldiers. The conflict escalated as Kurdish militant attacks occurred in urban spaces in the southeast but also reached as far as Ankara and Istanbul.

In October 2015 an even more devastating ISIL attack took the lives of over 100 attending a peace rally in Ankara. Many saw both the Suruç and Ankara attacks as displays of negligence on behalf of the government to effectively counter ISIL and prevent attacks on Kurds within Turkey.

Others believed that the Turkish government and ISIL were directly collaborating. These allegations may have been further exacerbated by the controversy over Cumhuriyet’s scandalous article and photos published in May 2015 alleging that the Turkish government was secretly providing arms to “jihadist” groups in Syria.

In September of 2015 the Turkish military initiated a new domestic military operation following the reinstatement of curfews in places the Turkish government considered to be high security risks like the city of Cizre. By December over 10,000 troops were deployed in southeast Turkey, primarily in Silopi and Cizre.

PKK fighters sectioned off parts of the cities with booby-traps and barricades as Turkish armed forces demolished entire neighborhoods and created a civilian displacement crisis.

The UNHRC has documented significant human rights abuses carried out by government security forces while other human rights organizations have also reported PKK violations.

Turkey’s New Strategy

The Turkish government developed their own brand of counterterrorism strategy beginning in the 1980’s and evolving over time. This strategy employed village guards, curfews, province-specific martial law, and curtailing civil liberties through anti-terrorism legislation.

Turkey’s counter-insurgency strategy has historically involved large-scale military operations. In the past Turkey’s accession process to the EU put certain restrictions on these policies. Now that Turkey has all but given up on the accession process these restraints are less relevant.

In mid-2016 the Turkish government began implementing a new security strategy. In September, Milliyet described the three major functions of this strategy as: “deployment, prevention and immediate intervention.” Turkey sought to expand local security apparatuses, emphasize preemptive security measures, and conduct new operations in Syria and Iraq to stop the flow of supplies and support to the PKK.

According to the government-linked think tank SETA, the new strategy has shifted toward “…non-stop anti-terrorist security and military operations not only in city centers, where the PKK-affiliated persons might live, but also in rural areas.” This new strategy also aims to “neutralize the PKK threat in its base.”

Other reports show increases in special operation forces with new tactical training, changes in command chains in order to improve adaptability, and higher levels of military-police collaboration. Blurring the line further between military and local police forces, in July of the same year the jandarma moved from the Turkish Armed Forces to the Ministry of the Interior. In accordance with this new strategy, government presence sprawls several levels of interaction from checkpoints to village guards to militarized operations to curfews.

Checkpoints

The revival of the conflict in 2015 prompted the resurgence of the village guard system, appropriation of land, new bases, and an intricate system of checkpoints along intersecting highways and villages. The use of internal checkpoints is certainly not novel: Human rights organizations have noted similar Israeli-run internal military checkpoints in the Palestinian West Bank.

The shift in 2016 to both an increase in number of checkpoints and in structure size demonstrates the new policy of containment and surveillance. Crucially, the bulk of the checkpoints observed develop more permanent structures after the end of major military operations in the area. We can see checkpoints appear in both urban and rural settings further corroborating the government’s shift to penetrating rural PKK strongholds with checkpoints at important junctures between villages and isolated communities.

Using available satellite imagery from February-May 2019, we can identify 1 mobile checkpoint, 7 “roadblock” checkpoints, 32 checkpoints with “outposts”, and 33 “overhead structures” across 11 provinces in southeast Turkey.

Types of checkpoints observed

*Roadblock Checkpoints: Obstructions in road to redirect traffic. No permanent structures.

*Outpost Checkpoints: Structures, towers, small buildings that function as guardhouses.

*Overhead Structure Checkpoints: Large structures primarily at the base of large cities characterized by metal roofs covering at least one lane of traffic through which vehicles drive through

Total number of checkpoints per year by type:

| Type | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Roadblock | 19 | 16 | 8 | 7 |

| Outpost | 2 | 33 | 33 | 32 |

| Overhead structure | 0 | 1 | 25 | 33 |

Between February and September 2015 only five observable new roadblock and outpost checkpoints appeared across the conflict zone. It is likely that informal checkpoints as well as local curfews were more prominent during the early phases of the conflict.

In 2015 through mid-2016 the checkpoint structures observed appear in the provinces of Şırnak, Diyarbakır, and Hakkari where the TSK (Turkish Armed Forces) initially devoted its resources. In the provinces of Mardin, Siirt, and Muş checkpoints do not appear en masse. In these provinces PKK militants were allowed to entrench themselves in the cities as the TSK conducted operations in the previously mentioned hotspots.

By April of 2016 reconstruction projects were already being discussed in Cizre demonstrating that large scale military operations had ceased in Şırnak province. By June 2016 the conflict returned to rural settings from urban attacks, yet we can see more formalized checkpoint structures begin to develop around cities.

The checkpoints constructed in mid to late 2016 include more permanent features like outposts and towers. New roadblocks and outposts continue to appear in Şırnak and Diyarbakır beginning in July 2016. The majority of these checkpoints notably appeared after the government retook these cities. In May 2016 the TSK turned its forces toward Nusaybin and by late 2016 and early 2017 the majority of checkpoints were retroactively erected around the city. None of the checkpoints appeared in Nusaybin before July 2016.

The end of 2016 and early 2017 marks the beginning of the phase in which metal overhead structures appear around entrances to cities, marking the last phase in the observable evolution. Checkpoints that often began as roadblocks or checkpoints with small temporary buildings now added an additional tin overhead structure. Roadblock and outpost style checkpoints continued to be expanded with overhead structures through mid-2018.

Some cities, like Midyat, did not develop visibly identifiable checkpoints until late 2017 while other cities that had experienced violence never appeared to have satellite-visible checkpoints at all. There are several reasons why some checkpoints could be “missing.” As checkpoints have become frequent targets of attacks some cities may utilize mobile or informal checkpoints. Resources may also have been concentrated on the most contentious places of conflict (as we see with Cizre and Silopi). Lastly, updated satellite imagery may simply be lacking for many parts of the southeast.

Total number of checkpoints per province by type using satellite imagery from May 2019:

| Province | Roadblock | Outpost | Overhead |

| Agri | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Batman | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bingol | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Bitlis | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Diyarbakır | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Hakkari | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Mardin | 1 | 3 | 5 |

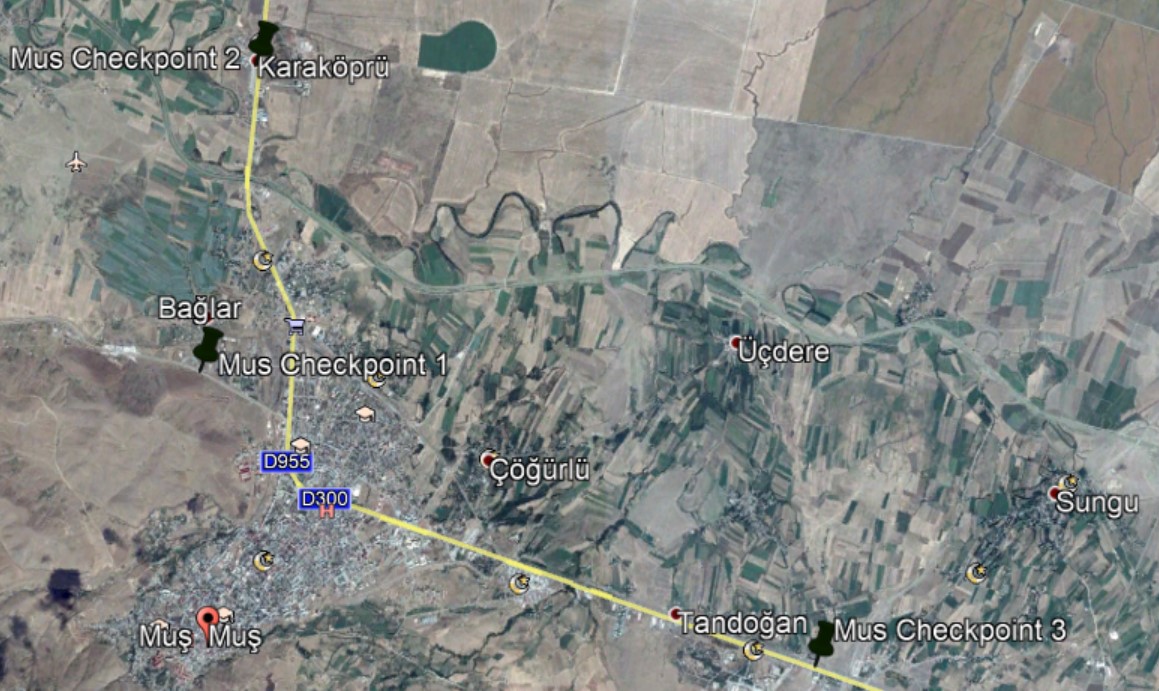

| Muş | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Siirt | 0 | 3 | 0 |

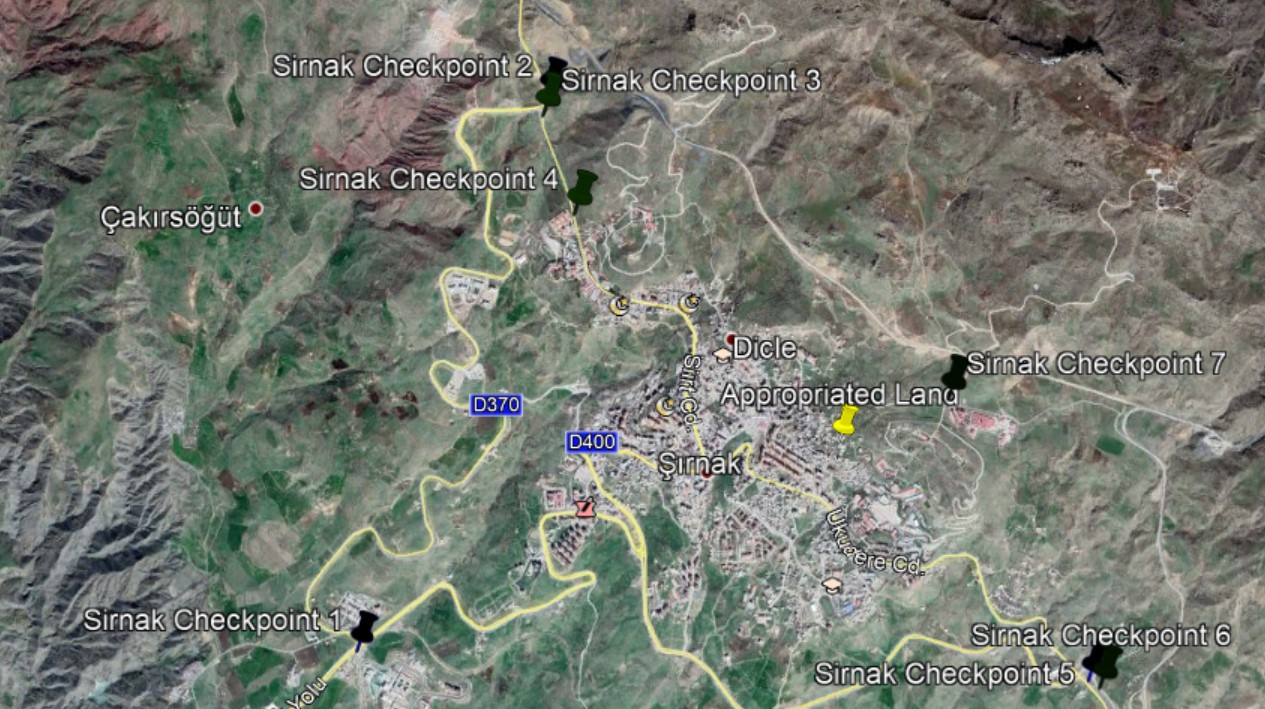

| Şırnak | 3 | 10 | 19 |

| Tunceli | 0 | 2 | 0 |

Village Guards

Since 1985, village guards have become a staple of Turkey’s counterterrorism strategy in the southeast. Village guards, often Kurdish, are used to legitimize surveillance and security in predominantly Kurdish rural areas by utilizing locals to take up arms. However, they have also played a controversial role amongst locals. Many accuse the village guard system of giving impunity to those who join. This allegation extends to drug trafficking and human rights abuses among what the PKK describes essentially as mercenaries of the Turkish government.

In 2007 the Turkish government began phasing out the village guards by offering competitive retirement plans, but the village guard system never truly diminished. Remnants of the 1980’s security structure remain in place today.

In 2017 an executive order expanded the role of village guards announcing 25,000 new positions. As of 2018 there were 52,395 village guards in Turkey and 19,912 volunteers. These new village guards are significantly younger (like most new hires in the police and military forces in Turkey since the start of the post-coup purge attempts). These guards play a psychological role in the conflict and are often targets of PKK attacks. A recent video distributed by a national Turkish news outlet emphasizes the addition of women village guards.

Land Appropriation

A series of official documents in 2016 show that the Turkish government approved the appropriation of a total of about 45 acres of land specifically allotted for new “Police Security Points.” The government passed four pieces of legislation detailing the appropriation of land in eleven districts for “police security points”:

January 25, 2016: 16,807,663.1 square feet

April 5, 2016: 2,400,674.94 square feet

April 25, 2016: 460,167.93 square feet

June 20, 2016: 69,427.22 square feet

Total land appropriated: 19,33,833.19 square feet

These plots of land vary from locations on hilltops overlooking cities to small inner-city sites. Most of the appropriated land is in southeast provinces and corresponds to hotspots of conflict similar to the current system of checkpoints. While construction of these new bases and checkpoints has already begun in some provinces, most of the appropriated parcels remain empty. These land allocations and their slow construction indicates Turkey’s long-term strategy to keep a strong military presence in the areas. Unlike mobile checkpoints, these structures insinuate permanent fixtures in these cities.

In mid-2017 we can see construction of what appear to be bases on some of the land allocated in 2016. The photos below show the construction of a base in Ergani, Diyarbakır on a parcel of land listed in one of the pieces of legislation passed in 2016:

Case Studies

These case studies show the variety of checkpoints across the region from urban to rural settings. Many of the checkpoints observed by satellite imagery also appear in reports, videos, or photographs. Each example displays a type of checkpoint (roadblock checkpoint, checkpoint with outposts, checkpoint with overhead structure) and a more in-depth description of the context of the installment of the checkpoints in each city.

Muş

Since 2015 several bombings and PKK attacks have occurred in this mountainous province northwest of Lake Van. In 2016 a bombing killed two soldiers, an attack on a train in Yorecik derailed a passenger train, and an attack on a police station in a village in Muş injured 3 village guards. From 2015 to 2018 curfews were imposed in the province seven times in Varto, Malazgirt, and Merkez. Conflict between the PKK and local military and police forces continues. In 2018, five people were killed in Varto, Muş and in February of this year Muş provincial authorities banned demonstrations for five days.

As of May 2018 one news agency reported that there are 11 checkpoints in the city of Muş. The three that are observable by satellite imagery follow the standard pattern of transition from no visible checkpoint to construction of limited structures and blast walls in mid-2016 to the addition of tin-roof overhead structures in early 2018. Additional sources corroborate the use of other less formal checkpoints throughout the province of Muş in the “forest”.

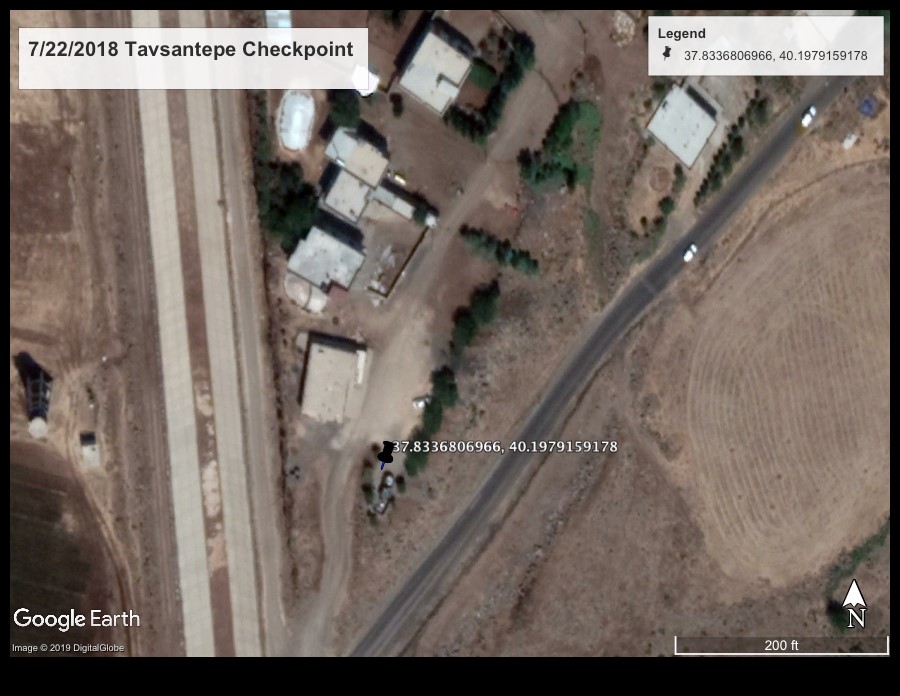

Village Guard: Tavşantepe

A video shared in July 2018 shows an Otokar Cobra at the entrance of the small village of Tavşantepe which is home to about 500 people in Diyarbakır’s Bağlar district. Security infrastructure, either in the form of armored vehicles or small temporary buildings, is visible via satellite imagery in this spot from May 2017 up until the most recent imagery in 2018. Conflict with security forces is not new to Tavşantepe and the continued and intensified quasi-military presence has had a negative effect on the town according to some locals.

A local news station interviewed residents who complained that the police used the mosque as sleeping quarters, threatened and physically abused them, interfered in voting procedures, and generally frightened the town. One resident explained that if the checkpoint is not removed he, and the rest of the town, would have to leave. Tavşantepe is only one example of potentially amplified consequences of checkpoints in more rural settings.

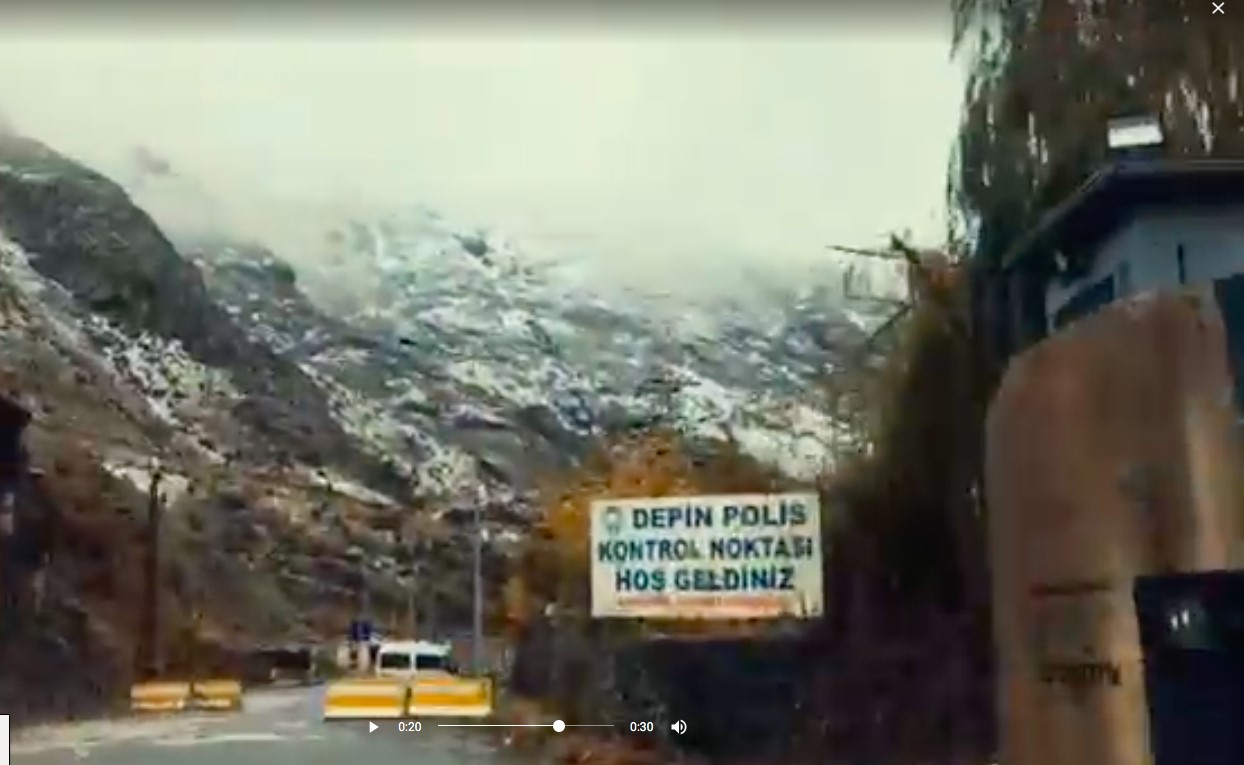

Unmanned Checkpoint: Bitlis

According to one local newspaper, 24 hour unmanned checkpoints were installed at all entrances to the city Bitlis in November 2016. However, only one two-way checkpoint could be found via satellite imagery. This checkpoint appears to be the same as the one pictured in the Ilka article. The creation of unmanned checkpoints is a response to the resurgence of PKK car bomb attacks on checkpoints. This checkpoint also points to greater collaboration between the militarized jandarma, local police officers, and village guards. Each of these security personnel operate the checkpoints at different times from a structure 50 meters away.

Tunceli Checkpoint Shooting May 2017

Tunceli has been a hotspot for PKK conflict since the 1980’s. One year before the end of the ceasefire in 2015 300 residents of Tunceli protested the construction of two new “kalekol” stations on top of a nearby mountain in the village of Sutluce. Two people were reportedly injured and gas bombs were used to break up the crowd.

PKK attacks on checkpoints are historically commonplace. In May 2017 a PKK insurgent drove up to a checkpoint in rural Tunceli (map below) with a VBIED (vehicle borne improvised explosive device) and was killed by two security officers. The bomb did not go off. Local news sources showed a video of the shooting as well as blurred images of the insurgent’s body.

A still from a video showing Turkish officers exchanging fire with a PKK combatant at an outpost checkpoint in Tunceli

Overhead Structure: Şırnak

The province of Şırnak incurred some of the heaviest structural damage and was the scene of some of the most intense urban fighting. According to Ahval, this checkpoint (pictured below) is one of 29 in the Şırnak province as of July 2018. HDP representative Huseyin Kacmaz Mezopotamya Ajansi’s article on Twitter noting that OHAL has ended yet the checkpoints remain.

Cizre Checkpoint: Transformation Into A Base

Cizre, a city also located within the Şırnak province, was at the center of the 2015 conflict. In 2016 a two-way outpost checkpoint appeared along an important interlocking highway northeast of the city of Cizre. In January of 2017 construction began on a large base. By late 2018 satellite imagery shows a fully constructed base and an overhead structure. This checkpoint evolved from a roadblock into a fortified base with a watchtower indicating that there is now a more permanent military presence in Cizre in the aftermath of the conflict.

Hakkari Bridge Checkpoint: Cobra Visible

Hakkari is a province with limited satellite imagery and important areas of conflict. Satellite imagery is missing in much of the province, including in a band around a prominent military base in Çukurca.

Hakkari contains many mountainous outposts in which the PKK hides and conducts attacks. However, imagery and video show a two way checkpoint on the main highway at the bridge approaching the only entrance to the city of Hakkari. The first checkpoint at this bridge appears in 2013 and the second in 2015. A video (screenshots below) uploaded to Google Maps appears to show an Otokar Cobra armored vehicle at the entrance to the checkpoint.

Conclusion

The local municipal election in Turkey on March 31, 2019 showcased an interesting development in the southeast: the province of Şırnak, an HDP stronghold, elected an AKP mayor. In the 2014 municipal elections and the 2018 general elections Şırnak had voted overwhelming for HDP. President Erdoğan said that Şırnak voted for “security” and against the PKK. In essence Erdoğan claims that the new counterterrorism strategy in Şırnak was recognized for its success in providing stability to the province and that the AKP win reflects that residents trust in the government to end the conflict and safeguard local interests. Alternative explanations provide, perhaps, a more all-encompassing diagnosis of the electoral win.

Ankara’s response to the resurgence of the PKK in Şırnak isn’t limited to checkpoints and security measures. Erdoğan has also attempted to alter the political administration. In the aftermath of the 2015 conflict 11 mayors were detained and jailed in Şırnak. In total 84 co-mayors and 17 deputies from the HDP were detained in the southeast since 2015. In addition to these arrests HDP deputy Hüseyin Kaçmaz shared a video alleging that security forces were deployed to Şırnak Merkez to distribute illegitimate voters to the polls. Many other residents shared photos of large convoys of soldiers allegedly being transported to and from the polls. Moreover the fact that many people have not yet been able to return to their homes adds another layer of complexity to the election results. Perhaps most representative of the current state of Şırnak is this video of HDP officials driving past several HESCO barriers through a checkpoint on their way to Şırnak in preparation for the election:

The checkpoints observed in this report are only one component of a larger counterterrorism strategy focused on rupturing PKK leadership structures, destroying strongholds, and demoralizing local populations. The future of the YPG will play a defining role in the fate of the PKK in Turkey. Turkey will do whatever it can to prevent an autonomous Kurdish region across its border. Turkey’s anti-PKK operations have continued to expand, both inside its borders and out. Increased military activity Syria and Iraq, such as the May 2019 Operation Claw demonstrate the increasing importance of these checkpoints not just for monitoring domestic populations, but also for surveilling transnational movement.

The resurgence of the Turkish government’s armed conflict with the PKK necessitated that the government consider a new counterterrorism strategy. Yet, despite their claims otherwise the Turkish government has shown little creativity in implementing new policies to effectively prevent conflict. Their policies stipulate short-term military procedures coupled with restriction of movement, political oppression, and greater reach into all aspects of life in the southeast insinuating that the administration has no intent to demilitarize the region in the near future.