Remnants Of The Deiri Opposition: Contention And Controversy In North Aleppo

Since the onset of its direct intervention in Syria, Turkey has struggled to create stability in northern Aleppo. Writing in mid-2017, Aaron Stein and others attributed this to the Turkish development and support of two conflicting security apparatuses; the newly created local police forces and existent militant opposition, as well as local council governance structures being held “subservient to Turkish political control, undermining their ability to represent the local population.”

Bouts of infighting between competing militant factions, in which several small groups originating from northeastern Syria have been heavily represented, have also frequently occurred.

These groups are Tajammu’ Ahrar al-Sharqiya (“Gathering of the Freemen of the East”), Jaysh al-Sharqiya (“Army of the East”), and Tajammu’ Shuhada al-Sharqiya (“Gathering of the Martyrs of the East”), three factions largely made up of fighters originally from the Syrian governorate of Deir ez-Zour.

As is common among Arab populations of eastern Syria, many of these fighters come from tribal backgrounds. However, it’s not clear how much of a role this plays within these groups exiled to northwestern Syria.

As the oldest and presumably largest, Ahrar al-Sharqiya has been particularly notorious since its formation, being at the center of incidents involving threatening U.S. special forces, an attempted Salafi proselytization campaign in Afrin, as well as a host of crimes and human rights abuse allegations.

While these “Sharqiya” groups exist under Turkish patronage and are thought of as potentially key proxies in rumored future campaigns against the Syrian Democratic Forces east of the Euphrates, the constant controversy surrounding them demonstrates how Turkey lacks control over them.

Syria’s east, particularly in the Euphrates river valley, was an opposition stronghold early in the war. This was due to a number of factors, such as the regime’s attention being focused on Syria’s western cities and coast, as well as a local population of largely economically-alienated Sunnis, often of conservative persuasions.

The region’s location turned it a key geographic node in the Sunni insurgency of the Iraq War, and with fighting against the Syrian regime broke out in late 2011, many of these Islamist networks proved to remain intact. As in other parts of Syria, the anti-Assad militant groups that sprung up in the east were an amorphous range of factions, including everything from secularist Syrian military defectors to outright al-Qaeda aligned jihadists.

The latter end of the spectrum soon came to dominate the opposition in Deir ez-Zour, particularly involving the well-known groups: Jabhat al-Nusra, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (a.k.a. ISIS), Harakat Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiya, and the Saudi-backed Madkhali–linked outfit Jabhat al-Asala wa’l-Tanmiya.

In early 2014, as open war broke out between ISIS and all other anti-Assad factions, the former quickly seized the east, leaving opposition militants the option of surrendering, dying, or fleeing.

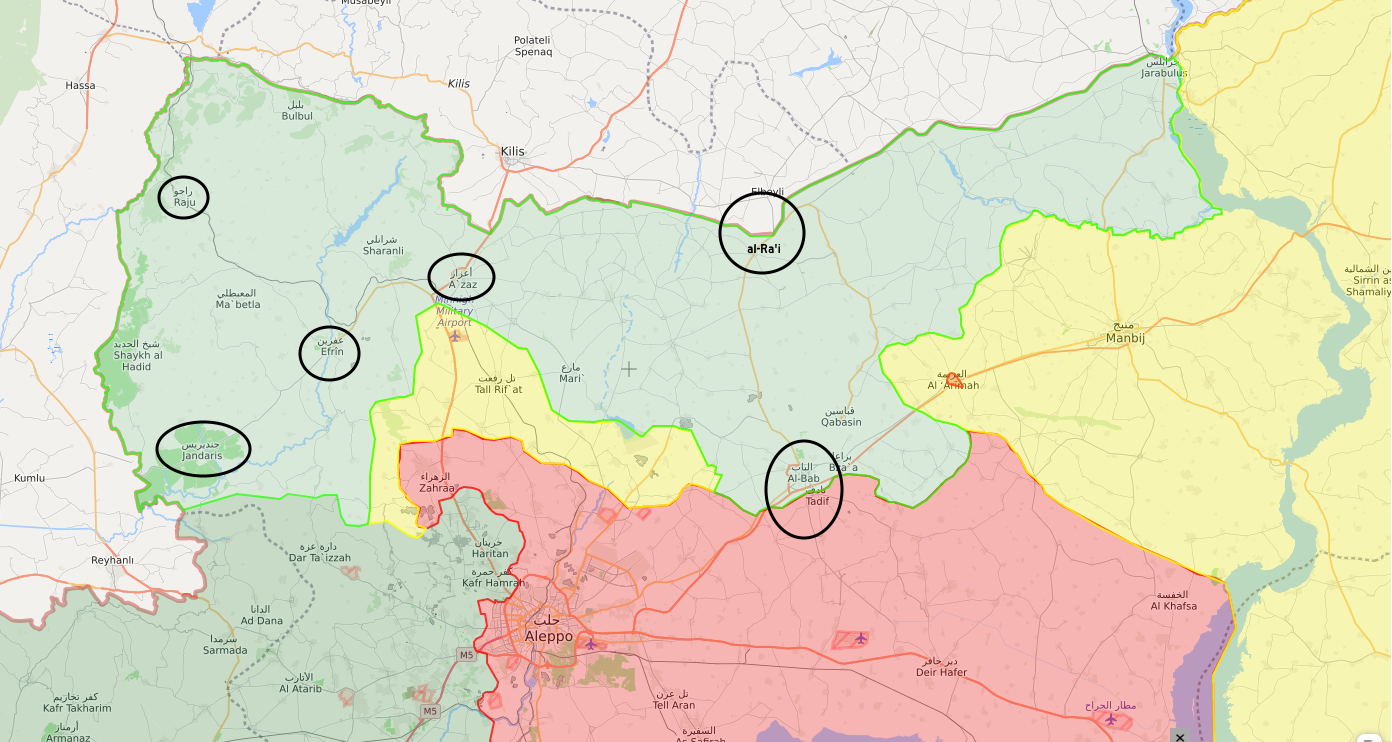

Map showing the directions opposition fighters fled, following the ISIS capture of eastern Syria, summer 2014 (map by Aram Shabanian)

Those that fled made their way across the desert to the west — to opposition-held parts of Syria such as Dara’a, Qalamoun and the Badiyah (the sparsely populated regions to the north and east of Damascus), as well as Idlib.

Dara’a attracted a major Jabhat al-Nusra contingent, including Iraqi-born Shura Council member Abu Maria al-Qahtani. Qalamoun and the Badiyah fronts saw the creation of new Deiri exile formed factions, such as Jaysh Usud al-Sharqiya, while established local groups absorbed fleeing fighters as well.

Less is known about the flight to Idlib, however it appears that many fleeing militants belonging to nationwide factions, such as Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham, maintained their membership upon arrival.

Tajammu’ Ahrar al-Sharqiya’s formation was formally announced by video in January 2016. Shot in rural northern Aleppo, it features a short statement read in front of approximately 50 fighters and six technicals.

While it has long been rumored that aforementioned Jabhat al-Nusra commander Abu Maria al-Qahtani was involved in the group’s creation, there is appears to be no evidence proving a direct link. What is clear is that much of the group and its leadership had been members of hardline Islamist faction Ahrar al-Sham prior to and following the ISIS takeover of Syria’s east.

Many Ahrar al-Sharqiya fighters had been involved in the Deiri opposition early on, and given Jabhat al-Nusra’s prominent role, it’s likely the group includes former Nusra members, as well as others who had been in close contact with Qahtani back then.

It’s unclear what incentivized the split from Ahrar al-Sham and the creation of a new faction, however, it’s likely that the group’s eastern roots motivated them to focus on the fight against the Islamic State at the time occurring in northern Aleppo.

Early in their history, Ahrar al-Sharqiya reportedly maintained a presence in Idlib, Latakia, and western Aleppo, yet its activity soon appeared to be relegated to northern Aleppo.

Following Operation Olive Branch, in which Ahrar al-Sharqiya primarily fought on the northwestern front, the group has been primarily located in Afrin city, the Afrin subdistrict of Rajo, as well as in al-Ra’i and al-Bab to the east.

In November of 2018, Ahrar al-Sharqiya’s media office claimed that the group had grown to 2,000 fighters and had lost 500 in the battle against the Islamic State. While they have undoubtedly grown since their founding, particularly with the increasing of Turkish support for the northern Aleppo opposition since the start of Operation Euphrates Shield, numbers of this magnitude cannot be verified through open source material.

It is generally assumed that Ahrar al-Sharqiya fields somewhere between several hundred to a thousand fighters. Part of the appeal the group has had is due to their perceived combat proficiency in comparison with other groups in the area, often working as the “spearhead” of rebel offensives.

As a part of the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army initiative, Ahrar al-Sharqiya receives material support from Turkey. This support constitutes some small arms and at least one APC used in Olive Branch. However, unlike a handful of groups particularly close to Turkey, such as Furqat al-Hamza, until very recently there appears to have been little effort to standardize and professionalize Ahrar al-Sharqiya fighters’ uniforms and kits.

The group has also not been the beneficiary of certain heavy weaponry and vehicles, such as F9 Panthera’s and new Turkish-manufactured technicals, that certain other groups have received since early 2018.

Unlike Furqat al-Hamza, with a truck-mounted Grad MRLS in its possession, Ahrar al-Sharqiya filmed itself in early May of 2019 firing a single Grad tube mounted on a tripod.

While a short video was published on June 8, 2019 showing an Ahrar al-Sharqiya fighter using what appears to be a US-made TOW ATGM system in southern Idlib, what this indicates is that stocks of this weapon still float around northern Syria. It is not an indication of a renewed external supply.

Despite this, the group’s leadership appears to enjoy good relations with Turkey, as commander Abu Hatem Shaqra was invited to meet with President Erdogan following the completion of the Afrin offensive. In February 2019, Abu Hatem posted a photo to his personal Twitter account showing him receiving an award from the local Turkish-backed security forces in the Afrin town of Rajo.

Ahrar al-Sharqiya commander Abu Hatem receiving an award from a representative of the Turkish-backed police force in Rajo

Ahrar al-Sharqiya first gained widespread notoriety for an incident that occurred on September 16, 2016 along the Syrian-Turkish border. Two videos came out that day from the town of al-Ra’i, one showing a convoy of local Aleppo group Liwa al-Mu’tasim that included embedded U.S. Special Forces, and another showing a crowd of angry rebel fighters protesting the American presence and denouncing their Syrian allies, calling them “American agents,” “dogs,” “pigs,” and part of a “Christian coalition.”

According to a statement released (English version here) by the group afterwards, their main objection to American presence in the area stemmed from American support for the Kurdish PYD, who Ahrar al-Sharqiya accused of adopting a “plan to destroy the unity of the Syrian land.”

This incident was widely framed as the U.S. being chased out of Syria by the opposition, and while that might not be an accurate portrayal of what occurred specifically that day in al-Ra’i, the limited DoD support for a select few northern Aleppo rebel groups ended soon after.

The group again gained mass attention in June of 2018 through its launch of a billboard campaign in Afrin. Several of the posters, put up on a few of Afrin’s main streets, urged female residents to follow hyper conservative interpretations of Islamic dress code, and were produced in conjunction with Idlib-based Salafi proselytization organization Markaz Idha’aat.

While in largely jihadi-dominated Idlib it is not uncommon to see women wearing the niqab — as in, being covered from head to toe in black — such style of dress is much less common in Euphrates Shield territory, and was likely non-existent in Afrin prior to the arrival of IDPs from suburban Damascus.

After causing an uproar, Ahrar al-Sharqiya’s signage was soon taken down by citizens and the local police, but the incident shows how Ahrar al-Sharqiya’s radical ideological inclinations have not dissipated, despite leaving the more Salafi-friendly climates of Deir ez-Zour and Idlib.

Such tendencies amongst the group’s members have also manifested themselves in the singing of songs (the fighter interviewed in the linked article was identified as an Ahrar al-Sharqiya member by author Louisa Loveluck) aligning their fight in Afrin with historic transnational jihad and issuing violent threats directed against “the atheist Kurds.”

Outside of these two noted incidents, Ahrar al-Sharqiya members have been involved in dozens of violent disputes with other northern Aleppo factions as well as local civilians. Most notable was one such bout of infighting, taking place just days after the capture of Afrin, in which fighting with Furqat al-Hamza broke out in multiple locations across northern Aleppo, allegedly over loot. Members of Ahrar al-Sharqiya have both committed and been accused of a litany of crimes and abuses, such as looting, kidnapping, and murder.

Images and videos have been posted by official and affiliated social media accounts showing fighters having beheaded enemy corpses, as well as committing field executions.

For example, this video from September 2016 shows that members of the group executed an alleged ISIS fighter, while the December 2017 video detailed in this report by pro-opposition SMART news agency shows a civilian accused of assisting the SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces) being tortured and executed.

Much less information is readily available regarding Jaysh al-Sharqiya. The group’s formation appears to have been declared by press release (English version here) on September 23, 2017, which identified its membership as made up of Deir ez-Zour, Hasakah, and Raqqa natives and named a Major Hussein Hamadi as its commander.

However, a month prior, a group of the same name was mentioned in a document as forming an interim committee of military and political leaders from the eastern provinces, signed by a Major Hussein Abu Ali.

Days after the official announcement, Hussein Hamadi was interviewed by pro-opposition Nedaa’ news agency. Hamadi stated the groups intentions of returning to Deir ez-Zour, claimed that they field 1,000 fighters, and listed fifteen pre-2014 Deiri factions represented within Jaysh al-Sharqiya.

While we were only able to find information on several of these factions, they include Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Asala wa’l-Tanmiya affiliated groups. While unconfirmed by other sources, a February 2016 Facebook post by a news organization focused on eastern Syria mentions a Major Hussein Hamadi as being injured in a northern Aleppo battle and identifies him as a member of Ahrar al-Sharqiya. It’s quite possible that the group was largely formed by other former Ahrar al-Sharqiya fighters as well.

Despite Hamadi’s September 2017 claim of commanding over a thousand fighters, it’s unclear whether this is an accurate statement, Judging by media put out by Jaysh al-Sharqiya over the last year and half, their manpower appears significantly smaller than Ahrar al-Sharqiya’s. However, both these groups did attract a new batch of displaced Deiri fighters, following the collapse and withdrawal from the rebel-held Eastern Qalamoun, northeast of Damascus.

During Operation Olive Branch, Jaysh al-Sharqiya fought on the Cindirese/Jandaris front in the district’s southwest, either alongside the Turkish 2nd Army or using vehicles with 2nd Army license plates (see APC in video).

Some of their videos from the campaign show them using one of the new Turkish-built technicals that only a few rebel groups have received, also indicating good relations with Ankara.

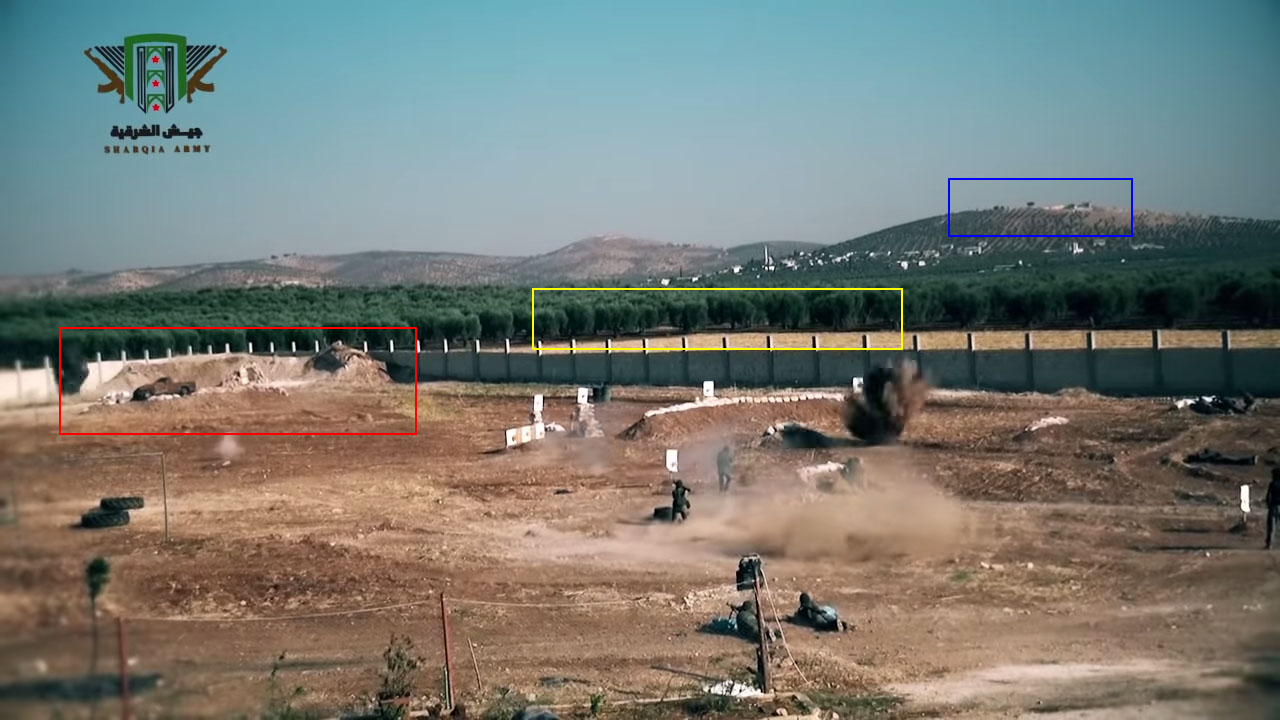

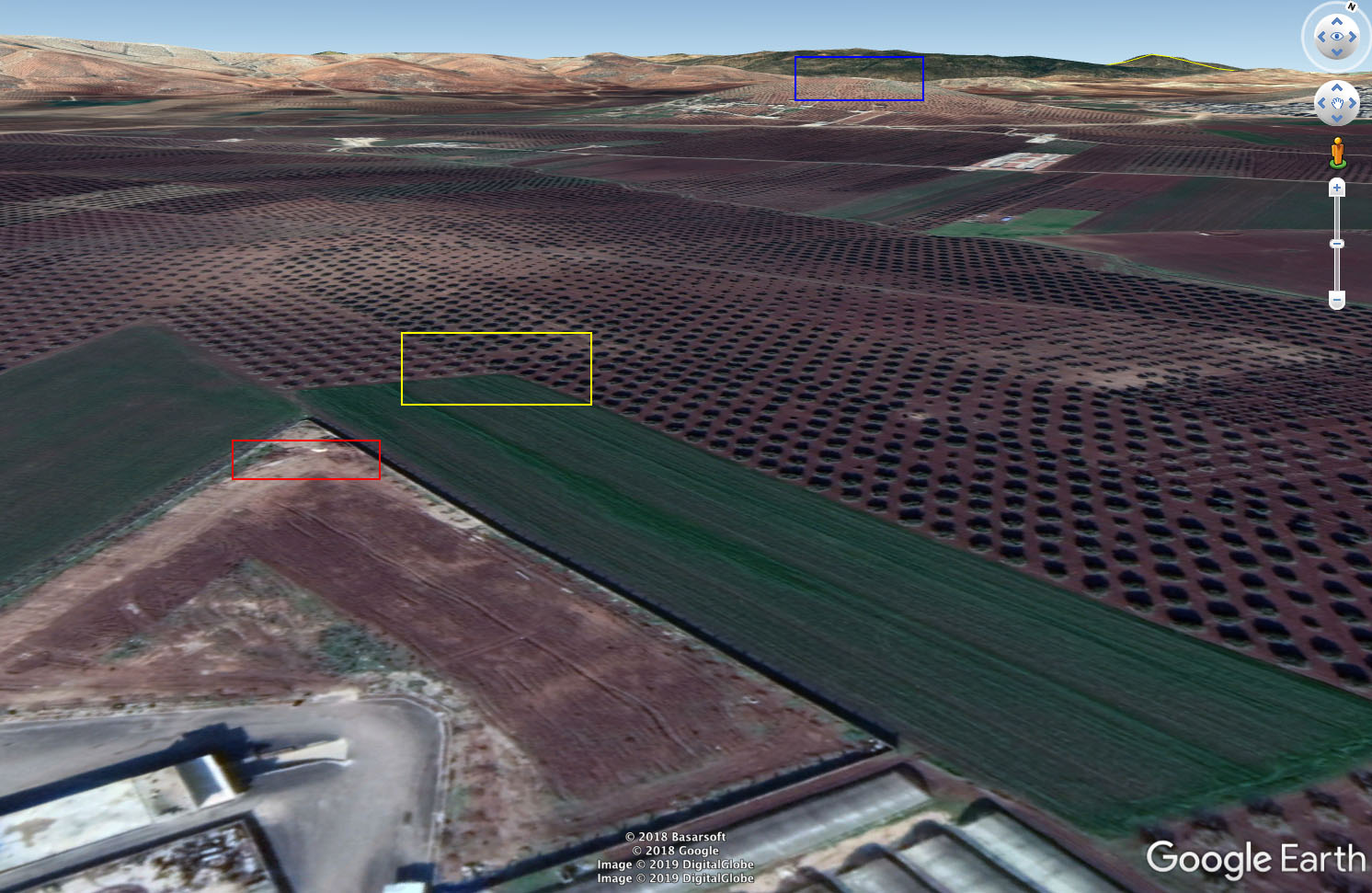

Since the end of Olive Branch, Jaysh al-Sharqiya has primarily remained within the Cindirese area. However, a video published in November 2018 shows the group using a training camp located just two kilometers southwest of Afrin city.

Jaysh al-Sharqiya has not been implicated in nearly as many controversies as Ahrar al-Sharqiya, though the two groups appear to enjoy close relations.

There have been multiple instances of them releasing joint statements on an array of topics since early 2018.

Several times, when Ahrar al-Sharqiya has gotten into violent disputes with other rebel factions, Jaysh al-Sharqiya has both voiced their support and worked as a mediator. Like many of the Turkish allied groups active in Afrin and the rest of northern Aleppo, Jaysh al-Sharqiya members have been accused of kidnap and torture, such as the April 2018 case of Farah al-Din Mohammed Othman reported by both pro-opposition and pro-YPG sources.

Othman had been kidnapped and tortured in the vicinity of Jandaris, allegedly by Jaysh al-Sharqiya fighters who demanded he turn over his house to the militants.

The third prominent eastern group active in northern Aleppo is Tajammu’ Shuhada al-Sharqiya.

Shuhada al-Sharqiya gained notoriety in November 2018, due to intense clashes between them and other opposition groups in western Afrin city, initiated by a Turkish “anti-corruption campaign.”

The group is a former Ahrar al-Sharqiya subfaction, once known as Katibat al-Hamza, and led to this day by a commander named Abu Khawla.

It’s unclear when the group was initially formed and whether it had always been a part of Ahrar al-Sharqiya. In July 2018, Shuhada al-Sharqiya launched an attack on regime positions in the al-Bab/Tadef area which led to their banishment from Ahrar al-Sharqiya for “violating command orders and acting individually.”

In a later statement, Abu Khawla blamed his banishment from Euphrates Shield territory on the group being prevented from “continuing the liberation of the whole of Syria…because of the international understandings,” referring to Turkish and Russian agreements.

In September and early October, Shuhada al-Sharqiya grew in size, folding three small groups of easterners into its ranks. However, on October 27, 2018, Abu Khawla announced the group was disbanded, a development attributed by others to Turkish pressure, which had continued following the Tadef incident in July of 2018.

This “disbandment” does not appear to have actually occurred. Intense clashes between the group and other rebels occurred in western Afrin city on November 18, 2018, preceded by the announcement of a Turkish-backed curfew and the “anti-corruption” campaign.

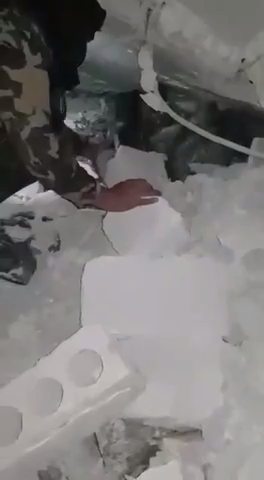

This day of clashes, largely occurring within Afrin’s Mahmudiyah neighborhood, included the use of heavy weapons leading to the destruction of buildings with Shuhada al-Sharqiya fighters trapped under rubble. After at least 25 fighters and civilian bystanders were reported killed, it appears that Jaysh al-Sharqiya stepped in and facilitated a deal in which Shuhada al-Sharqiya fighters and their families were guaranteed safe passage into Idlib.

After months of social media inactivity, Shuhada al-Sharqiya updated their Facebook page on May 16, 2019, changing their profile picture to an image featuring the logo of Hama-based rebel group Jaysh al-’Izza. Rather than the name they had been going by, Tajammu’ Shuhada al-Sharqiya, this emblem read Liwa’ Shuhada al-Sharqiya (“Eastern Martyrs Brigade”).

On the same day, they posted a document calling on fighters to immediately join them on the Hama frontlines. Jaysh al-Izza has subsequently denied that Shuhada al-Sharqiya has become one of its component groups.

The following week, Abu Khawla turned up in northern Aleppo seeking to recruit more fighters for the Hama battle, despite the existence of an outstanding arrest warrant for this rebel commander. Abu Khawla was arrested on May 27 by the Turkish-backed Military Police at a checkpoint between A’zaz and Afrin.

News of Abu Khawla’s arrest soon reverberated through Syria’s north, leading to clashes in multiple locations between Ahrar al-Sharqiya and the military police supported by non-Deiri opposition groups. Shuhada al-Sharqiya members have since threatened to abandon their frontline positions and return to northern Aleppo unless Abu Khawla is released.

Map of northwestern Aleppo, including Afrin and ‘Euphrates Shield’ territory (map by Aram Shabanian, base map by liveuamap)

Developments following the Turkish-backed invasion of Afrin have further demonstrated the internal instability existing within the northern Aleppo opposition.

While other, more prominent groups have contributed to this factional discord and the widespread allegations of human rights abuses, the Deiri outfits have demonstrated remarkable proficiency in creating their own controversies.

The fighters of Ahrar al-Sharqiya, the largest of the three, have repeatedly displayed violently opportunist and ideologically radical behavior, but despite this track record, its leadership still appears to maintain good relations with Turkish officials and their civilian proxies in Syria.

As a smaller and perhaps even more chaos-inducing faction, Shuhada al-Sharqiya drew the ire of the Turks by attacking the regime without Ankara’s permission and was quickly tossed aside.

Jaysh al-Sharqiya, which seems to have the closest operational relationship with Turkey, still shows close affinities to both groups, presumably out of Deiri loyalty, and has acted as an interlocutor between them and the rest of the Turkish-backed opposition in northern Aleppo.

Turkey clearly hopes to develop dependent indigenous proxies in case of a future anti-SDF campaign east of the Euphrates. However, the Deiri rebels’ freewheeling independent streak shows no sign of being corralled.

With Ahrar al-Sharqiya and Jaysh al-Sharqiya’s recent entrance into the Hama battle, it appears that both Turkey’s designs on eastern Syria as well as its attempts at deconfliction have only been further obstructed.