Heavy Rains in Hasakah: An Open-Source Analysis of Catastrophic Damage

When the season of heavy rainfall began in war-torn Syria, the misery local residents and internally displaced persons (IDPs) have faced over the years was compounded by environmental setbacks. This open-source monitoring blog of the situation in north eastern Syria, currently controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), will look how the rains in the area have impacted the living and working conditions of civilians in local communities and IDP camps.

The information available is based solely on remote sensing and open source information collected over the period of November and December 2018. It is, overall, a quite telling collection of evidence of how climatic and environmental conditions impact conflict areas. It can serve as a warning for humanitarian agencies and relevant authorities to include the wider dimensions of geography, climate and conflict pollution in planning and reconstruction operations.

A rapid remote sensing and open-source scan of environmentally vulnerable areas as profiled in this piece demonstrates the following data:

- Oil spills at the Gir Zero oil station in northeast Syria that resulted in localized pollution

- Heavy rainfall causing local rivers and creeks contaminated with oil waste to overflow, affecting at least 2 km2

of agricultural land - Over a third of Arisha’s IDP flushed away by rising water levels in the Hasakah water basin, likely affecting thousands of people

Background

Oil forms the backbone of the economy in northeast Syria and the landscape in the Jazira canton in Hasakah governorate, also known as Rojava, is dotted with rusty pumpjacks. The Kurdish self-administration is struggling with outdated oil infrastructure that initially crumbled during the start of the conflict.

Due to limitations on import of equipment and lack of sufficient expertise, the local industry functions on a minimal level and is mainly focussed on exports of crude. Semi-professional and artisanal oil refining is controlled by the local authorities. We covered makeshift refining in our 2017 and 2018 open-source blogs Hazardous Legacies and Nefarious Negligence and in the 2016 PAX publication Scorched Earth and Scarred Lives. The lack of oil waste storage, proper pipelines, and processing facilities resulted in local hotspots of oil pollution throughout the region, as can be seen via open-source satellite imagery.

Rmeilan, a small town in the east of the canton, is the oil capital of Rojava. There, the Gir Zero oil station functions as the main crude oil collection point before the oil is transported by trucks to basically everywhere. Before the war, the crude was transported through a pipeline to the Homs refinery, which prevented unsafe practices such as makeshift refining and guaranteed a safe mode of transport. Now, daily truckloads of crude and semi-processed oil are transported to various end users via poor road infrastructure, and accidents occur frequently, as noted by local journalists traveling in the region:

An oil truck following a crash on the road from Qamishlo to Kobani. Posted on December 2, 2018 by Kamiran Sadoun on Facebook

Tracking down leaks

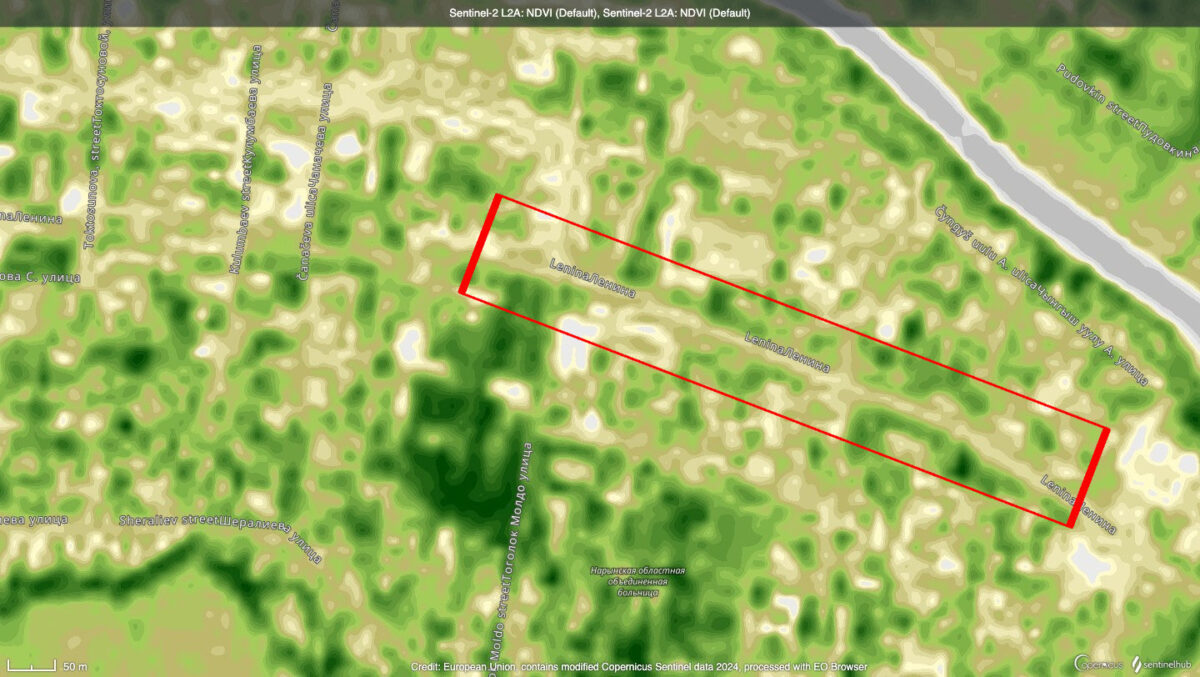

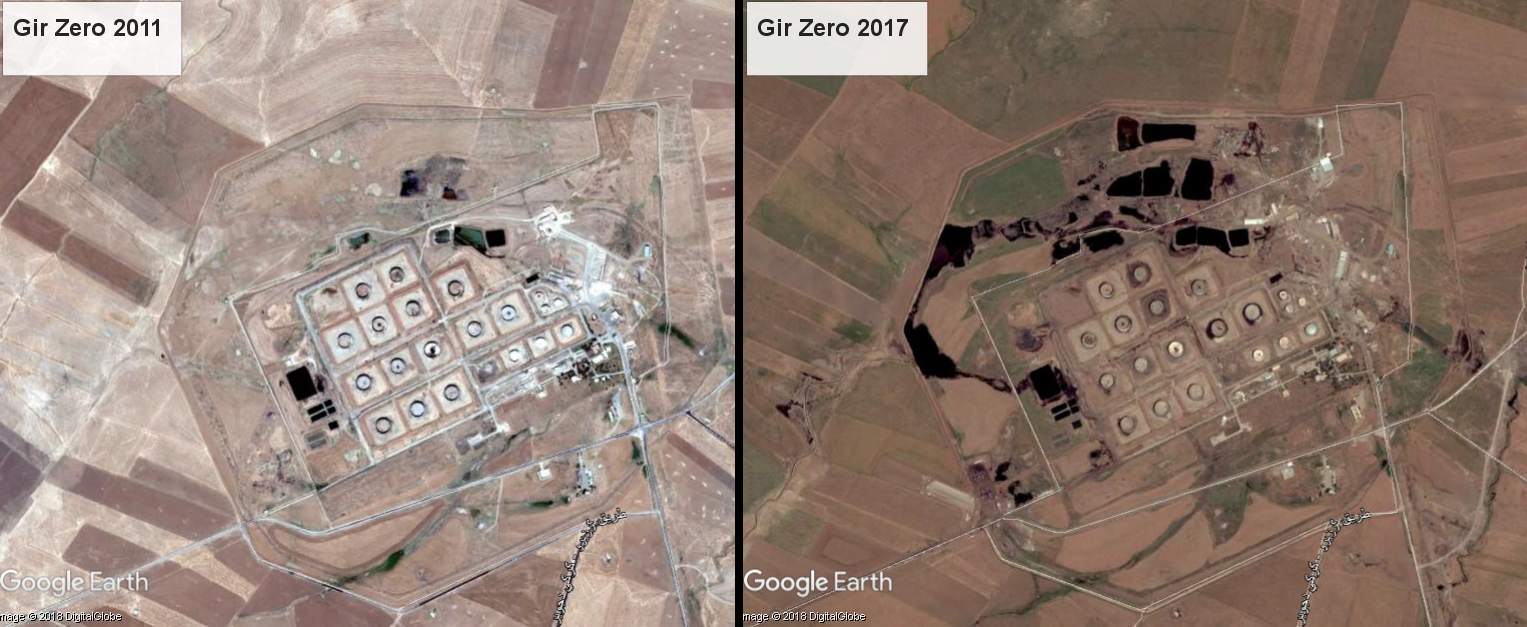

In early November of 2018, satellite imagery provided by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel 2 satellite through the Sentinelhub platform showed a leak at the oil storage reservoirs at Gir Zero. This collection point of crude was already undergoing difficulties both with the oil itself and with waste storage, with more open-air oil reservoirs built at the location, as visible through Google Earth from the period of 2011-2017.

Gir Zero Oil facility

With time, more leaks of sludge and/or crude oil occurred at this location. Provisional security through a soil barrier around the location should have prevented major accidents, but the oil waste found its way into local rivers and creeks, as can be seen from satellite imagery:

Sentinel-2 image with Vegetatoin Index (False Colour) of Rmeilan oil field, October 2018

Between November 13 and 16 of 2018, an incident occurred at Gir Zero, causing the spill of crude oil or oil waste, as satellite imagery provided by Planet Labs shows. This was likely due to the heavy rainfall, but other reasons cannot be excluded.

Gir Zero Oil spill captured with Planet Labs imagery, Nov-Dec 2018

Using the Sentinel Hub Earth Observation Browser with the vegetation index, the oil spill creates more contrast with the vegetation background.

Gir Zero oil spill captured with Sentine-2 by Sentinel Hub, Nov-Dec 2018

Sadly, the contamination didn’t stop there. As the black rivers of oil found their way south, heavy rains also resulted in flooding. At one location, close to the village of Tall Mashan, a massive flood of oil polluted water spread over the agricultural land on the first days of December 2018. As a result, at least 2 km2 of land was contaminated by oil. Again, Sentinel Hub’s EO browser with vegetation index shows the contrast of the spill.

Flooded oil rivers captured with Sentinel-2, Nov-Dec 2018

Satellite imagery of eastern Syria by Digital Globe, dated December 15, 2018, also partly shows the spill, with the nearby abandoned makeshift oil refineries in the picture:

Oil spill captured by Digital Globe preview, Dec 15, 2018

PAX visited this exact location in late November, and images gathered confirmed the rivers of oil. Meanwhile, shepherds were seen herding flocks of sheep on garbage dump sites nearby, highlighting the ways in which local environmental conditions affect residents. Local security personnel and civilians all raised concerns over the potential health impact of the continuous flows of oil waste through the creeks, while the thick black clouds of burning oil waste from local refineries darkened the horizon.

River with oil at Tall Mashin, November 2018. Wim Zwijnenburg

Rojava’s oil industry is regularly affected by similar incidents, and the outdated equipment, lack of sufficient expertise, certain climate conditions, and the threat of renewed conflict are capable of creating a far more devastating environmental disaster. Oil spills contaminate agricultural land, as well as surface and ground water, while the poorly functioning industry remains a risky working environment for local staff.

Semi-professional oil refineries on the road to Tall Mashin, November 2018. Wim Zwijnenburg

Both Increased droughts and excessive rainfall seem to further impact environmental conditions and the social-economic opportunities among residents of local communities.

The need for access to agricultural land is important to the local area. This is why limiting further setbacks to production of wheat and grain is crucial for recovery and reconstruction.

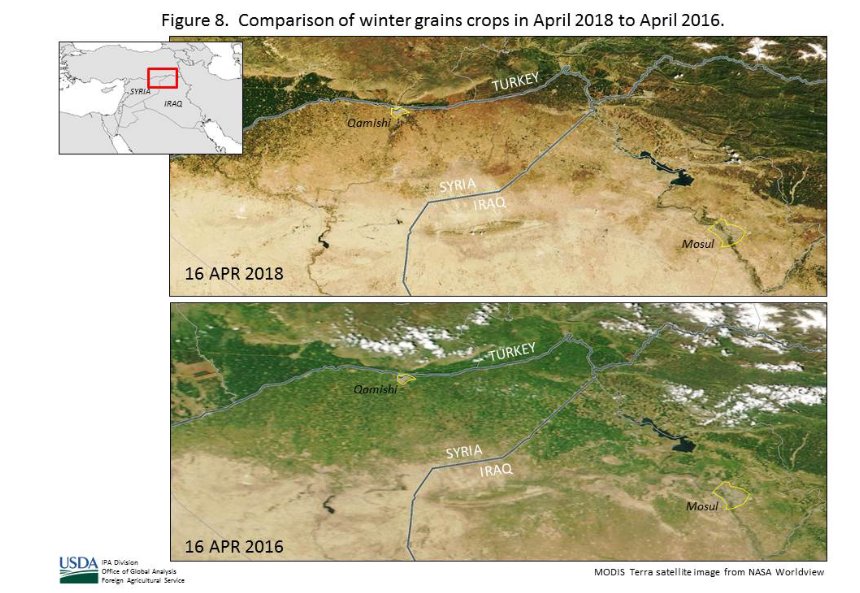

The U.S. Department of Agriculture released a report in May of 2018, warning of how the conflict impacts the growth of winter crops, and using satellite imagery to show the decrease in production of wheat and grain due lack of planting by farmers as well as less rainfall. The report states:

“Much of this region depends on irrigation so a lack of equipment and fuel due to the on-going conflict is expected to be a contributing factor rather than lack of water. (…) Syria and Iraq are food insecure nations that depend on imports of winter grains to meet domestic consumption demands. This year’s drought is a cause for concern. Syria’s winter grain production will be dramatically impacted”

As stated by the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) during the 2018 donor pledging conference on Syria, millions of Syrians depend on the agriculture sector:

“Much of the conflict has been concentrated in Syria’s main agriculture areas and the agricultural sector has been badly affected. FAO estimates total damage and losses to the sector in excess of $16 billion since the start of the conflict. Massive displacement, large-scale livestock loss, and widespread infrastructure damage have led to enormous declines in food production and record high food prices.”

In sum, poor maintenance of oil infrastructure, combined with changing climatic conditions, has resulted in a growing number of incidents that could seriously affect the environment, health and socio-economic conditions of the local population, with long-term, reverberating effects challenging recovery efforts.

Rains Affecting IDP Camps

Heavy rainfall has also had devastating impact on civilians who fled the violence in their hometowns and cities throughout Syria. According to a UN news report, over 250,000 people were affected by the record rainfall in northern Syria’s IDPs camps in Idlib and Aleppo, while another Flash Report by Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU) Syria, a national NGO coordinating humanitarian response, describes more specific issues with conditions in the camps.

The problems in northwest Syria are likely compounded by the massive scale of deforestation taking place due to the fact that people there need firewood, and to the fact that forests have been cut down for the smuggling of charcoal. The lack of forest to keep the soil in place during rainy seasons has resulted in increased soil erosion. Limited attempts are meanwhile undertaken for reforestation — in both the Kurdish part of northeast Syria as well as in Idlib and southern Syria.

Local opposition activists and media outlets have posted images and video footage from floods in the camps in both Idlib and Hama, northwest Syria, although the specific sites have not been located and/or verified.

Words can’t describe the devastating videos coming from the camps in northern Idlib. The situation is miserable and heartbreaking.#Syria #Idlib #Displaced #Refugees pic.twitter.com/BvrVx68FCN

— Husam Hezaber (@HusamHezaber) December 27, 2018

FLOODS sweeping thousands of IDP’s tents in northern Syria.#Syria #Idlib

YouTube link:https://t.co/KiIuxg8x02#MMC pic.twitter.com/GcDEk6hGYD

— مركز المعرة الإعلامي MMC (@maaramc12) December 27, 2018

One of the most starkly visual cases of the impact of heavy rainfall that can be observed using satellite imagery is the Arisha IDP camp. The camp, which is located south of the city of Hasakah at the bottom of the South Dam Reservoir, was set up in the beginning of July 2017, with the first tents appearing in August, as can be seen using Sentinel 2 data.

Arisha IDP first tents early August, captured with Sentinel-2, surrounded by the makeshift oil refineries

The camp developed rapidly as can been seen on by Planet Labs satellite imagery, with active makeshift oil refineries at the west side of the camp

Time lapse of the Arisha IDP camp build-up, July-August 2017

In February 2018, the camp was host to over 16,000 IDPs, while the current population is around 10,000. One main concern with the location of the site is that it was built between three major clusters of makeshift oil refineries, and is hence at risk from toxic waste which is the byproduct of oil refining. This was noted by the ICRC when they visited the location early August 2017:

“One of the camps, Arisha, is on the site of an old petroleum refinery. Toxic waste contaminates the water. But people have no choice and drink it anyway.”

This is how babies have a bath: In polluted water, full of insects and garbage. These children from #Raqqa & #DeirEzzor deserve better. pic.twitter.com/D4DdgxZySo

— ICRC Syria (@ICRC_sy) July 31, 2017

Sentinel-2 imagery with ICRC photo’s of Arisha IDP camp, next to the makeshift refineries, the black dots surrounding the site

When the rainy season started, the water levels in the South Dam Reservoir started to rise as well. Heavy rainfall in late December of 2018 destroyed a significant part of the location, flooding the tents and facilities at the site.

They have survived bombardment, the loss of loved ones, and desperate hunger. Now freezing winter floods are the challenge for almost 10,000 people stuck in Areesha camp in northeastern #Syria. pic.twitter.com/cONpZihyrr

— ICRC (@ICRC) December 20, 2018

Using data from Planet Labs, a time lapse of the period between November 20 and December 29, 2018 shows the devastating effect of rising water levels which wiped out at least a third of the campsite.

Planet Labs time lapse of the Arisha IDP camp flooding, Nov-Dec 2018

A small new settlement was quickly set up after the first major flood, as is visible from the December 29 imagery:

Planet Labs Imagery from Dec 29, 2018 showing newly build settlement

The rising water also swept away the abandoned makeshift oil refineries and the toxic waste left at these sites, spreading oil sludge and tar over the nearby lands. The long term implication of what happened is unclear, yet should be investigated to ensure that further exposure to hazardous materials could be avoided.

This situation should indeed strengthen the call made in 2017, in the Third United Nations Environmental Assembly (UNEA) resolution, titled “Pollution mitigation and control in areas affected by armed conflict of terrorism”. The resolution calls for states to closely cooperate in preventing, minimizing and mitigating the negative impacts of armed conflict or terrorism on the environment and participate in preparing national plans and strategies, as well as setting priorities for environmental assessment and remediation projects, including better data collection for identifying health outcomes and ensuring that the data is integrated into health registries and risk education programs.

Conclusion

Heavy rainfall has had a destructive impact on conflict affected northern Syria, causing polluted rivers to overflow onto agricultural lands in the oil rich Jazira canton, as well as causing local spills at oil storage sites. The weak regulatory system and crumbling oil infrastructure have worsened the situation, and if not addressed properly, the future will bring more of these serious environmental threats directly or indirectly caused by years of conflict. Meanwhile, rising water levels in Hasakah water basin resulted in the flooding of Arisha IDP camp, which is hosting over 10, 000 displaced Syrians. This site was already vulnerable spot due to the nearby situated toxic remnants of hundreds of makeshift oil refineries, which were polluting local water sources and exposed camp residents to hazardous materials.

These findings should reiterate the need for taking into account the careful planning for IDP living sites, as well as the need for improved data collection on potential environmental damage caused by crumbling critical infrastructure, including oil and water systems.

The author would like to thank Twitter user @obretix for additional feedback and Kamiran Sadoen for use of the damaged oil truck photo.