Investigating Houthi Claims of Drone Attacks on UAE Airports

Any news suggesting a Houthi “drone strike” or “ballistic missile” attack should not be downplayed by any of the parties involved in the conflict in Yemen. The last two years have seen the rise of the Houthi’s asymmetric capabilities, especially against Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Houthi sources, however, should not be used exclusively as evidence when investigating claims of drone attacks.

The asymmetric warfare strategy of using ballistic missiles and drones was announced by Abdul Malik Al-Houthi, leader of the Houthi group, last year. The group is facing off with the Saudi-led coalition which began its military campaign in Yemen back in March 2015. An official document was shared on social media, including open source platforms, to warn the coalition of its air strike campaign. The document warned international companies operating in the region to take necessary precautions.

Drone Capability

Open source investigation on the Houthi group’s official Telegram channel surfaces one claimed attack on Abu Dhabi Airport and six on internal fronts in Yemen such as Mockha, Marib and Al-Baydah. Ten other drone attacks were claimed to have been executed in the west coast against Yemen forces battling for Hodeidah governorate.

Here is the alleged Houthi drone strike data and information on active capability published on the Houthi Telegram channel on July 26, 2018:

Since July 26, the Houthis have claimed they have executed 21 drone related attacks and incursions. The Houthis claim to possess five different drone models according to the infographic disseminated on their official Telegram channel — if real, all should be capable of posing asymmetric security threats.

The Houthi group claim they possess the Hudhuh-1, Qasef-1, Raqeeb, Rased, and the Sammad drone which comes in three different configurations. According to the Conflict Armament Research (CAR), the Qasef-1 drone is not indigenously designed or constructed. CAR found that the drone was Iranian-manufactured in design and construction, based on one of their field investigations. This appears to support the claim by the Saudi-led coalition that Iran is providing material support to the Houthis. The other drones named by the Houthis have not been assessed for parts or origin.

Claims of Abu Dhabi Airport Attack

On July 26, the Houthi group claimed to have attacked Abu Dhabi Airport (AUH) in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with a drone dubbed Sammad-3, possessing a range of more than 1400 km, according to the Houthis. There is no verification, however, on whether the range stated by the Houthis is operationally factual. The Houthi group have not published any form of evidence to this day to support their claim of an attack at AUH. Instead, there are only infographics and statements to persuade the world of such an attack.

The UAE government denied that an attack occurred, Abu Dhabi Airport appeared to deny an attack had taken place, and tweeted about an “incident” involving a supply vehicle which had impacted the service of operations:

Abu Dhabi Airports can confirm that there has been an incident involving a supply vehicle in Terminal 1 airside area of the airport at approximately 4:00 pm today.This incident has not affected operations at AUH and flights continue to arrive and depart as scheduled. (1/2)

— Abu Dhabi Airport (@AUH) July 26, 2018

Following the “incident,” there was no immediate comment from the UAE government on reports of a drone attack. At the time, the Houthis posted on several open source platforms, including Telegram and Twitter, that an attack had taken place at the Abu Dhabi Airport.

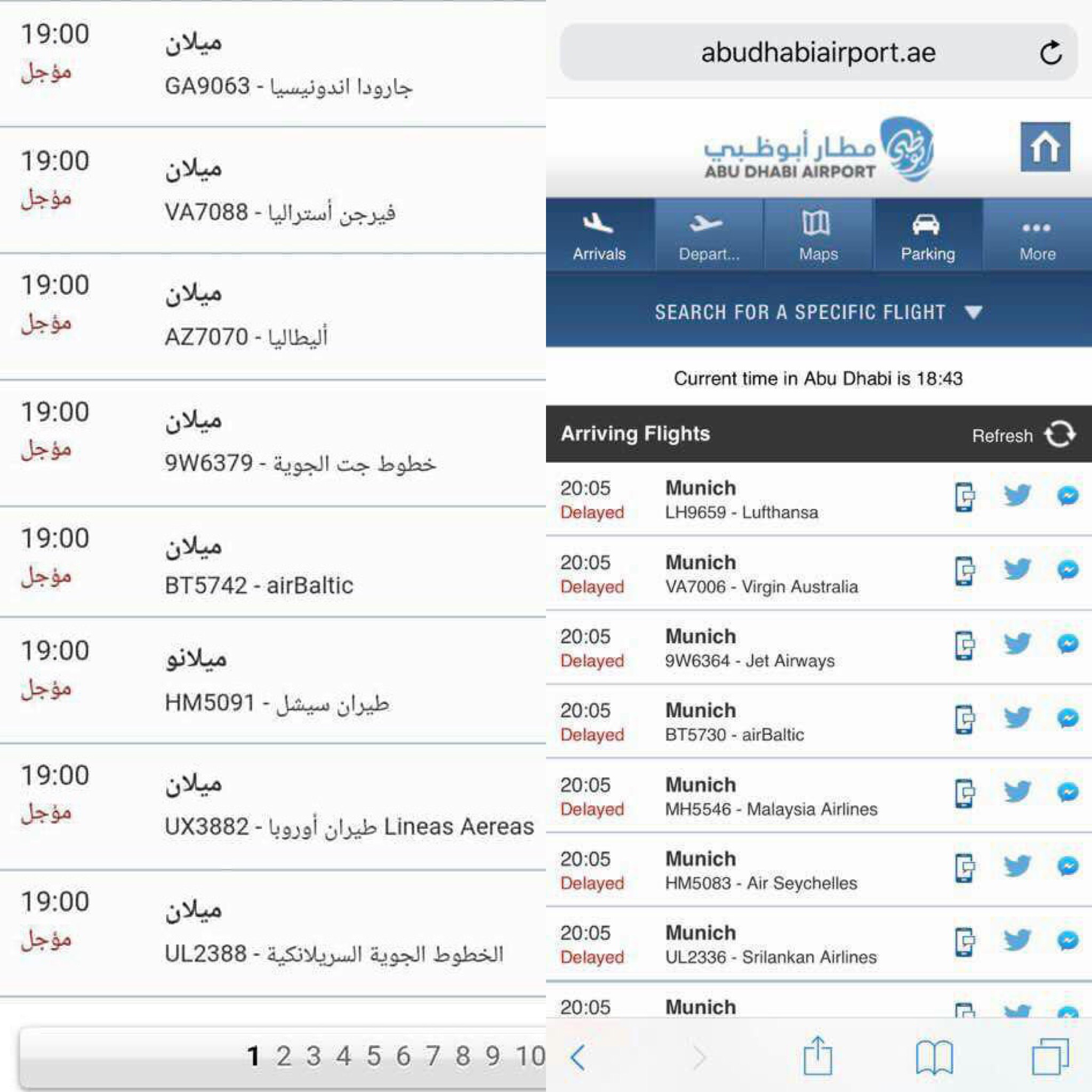

The official Houthi open source platforms and pro-Houthi chat forums began notifying followers, sending pictures of a list of flights the drone was alleged to have disrupted at AUH. However, the group failed to publish any video or images of this attack — and none have emerged from any other source.

Currently, there is no open source proof that any damage was inflicted at AUH, which calls into question whether an attack took place. Adding to this, thousands of civilians pass through AUH airport each day, no doubt in possession of a mobile phone with photo and video capability. The fact that no mobile capture evidence was uploaded to social media and that not a single passenger that day noticed an attack suggests that the attack did not take place.

Houthi propaganda images were shared on open source networks, including a screen grab of disrupted flights in Abu Dhabi:

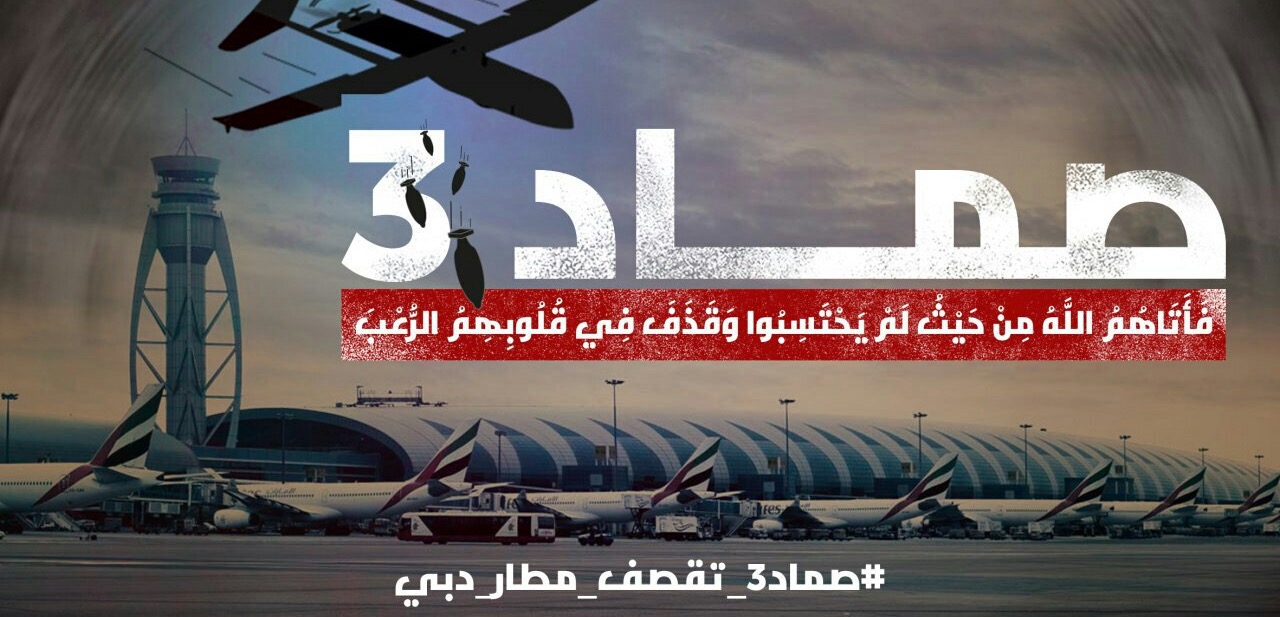

Houthi drone propaganda was on the increase hours after announcing the attack, and graphics were shared to support the group’s attack claims, yet they still do not support or verify whether an attack actually occurred.

Claims of Dubai Airport Attack

On August 27, the Houthis claimed they had attacked Dubai International Airport (DBX) in the UAE with a Sammad-3 drone. Dubai is some 1,200 kilometres away from Yemen and has the third busiest airport in the world, according to Airports Council International.

The Houthi-run Al-Masirah news site wrote about the alleged strike, while the armed group’s official Telegram and other open source platforms publicised that an “air strike on Dubai International Airport confirms that all areas of the UAE are in the range of strikes.” Adding to this, the Houthis claimed that “a blow” was achieved by interrupting airport activity for some time. A “blow” could insinuate a strike or DBIED attack, but there is no evidence again of a post-strike/attack scene or drone recovery from the alleged mission.

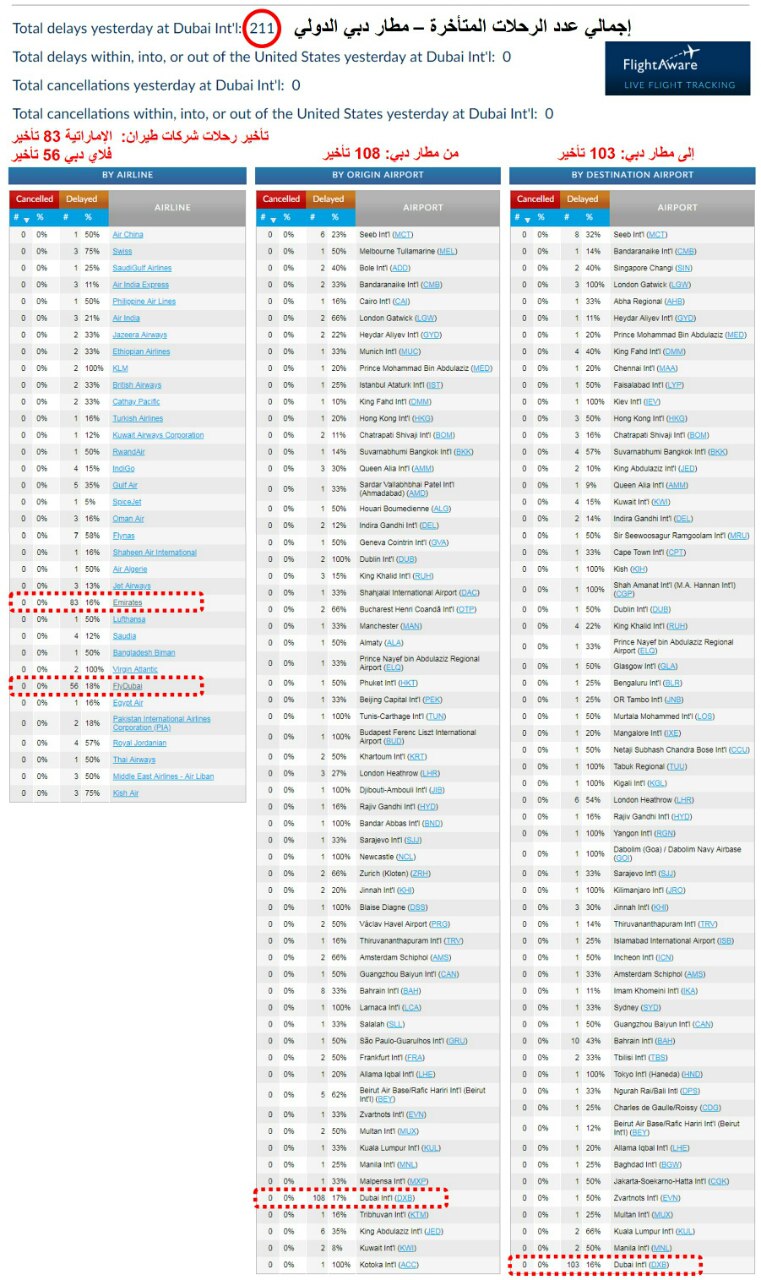

The following screen grab was shared on Houthi official and pro-Houthi open source platforms, claiming that disruption to flights in Dubai occurred as a result of the attack:

Although a disruption of some kind clearly took place, no evidence of an attack besides Houthi claims exists. And while DBX is much busier than AUH, no passenger seems to have recorded any potential evidence either. As seen with the alleged AUH attack on July 26, there was an increase of propaganda and pictures shared to highlight drone usage. Continued open source investigation has uncovered no evidence of an attack. Media posted to social media does not appear to show any damage caused to DBX.

Here is a Houthi propaganda image used in claims of an attack on DBX:

The UAE’s General Civil Aviation Authority responded by denying Houthi claims of an attack on DBX in a statement made via UAE-state run news agency WAM.

Yet previously, on July 18, the Houthi-run Al-Masirah claimed that Houthi “drone air forces” targeted Saudi Arabia’s Aramco oil refinery in Riyadh using an armed Sammad-2 drone – this time causing a fire.

Mohammad Abdu Salam Saleh, the Houthi military spokesman, weighed in on social media, claiming that the “operation by the drone air force is a strong start in a new stage of deterring the aggression”, echoing the asymmetric policy adopted by the Houthis. Aramco responded by saying there was a “limited” fire at the refinery due to “an operational incident”:

Saudi Aramco fire protection crews and Civil Defense have successfully controlled a minor fire due to an operational incident at the Riyadh Refinery today. No personnel are injured and no impact on operations.

— aramco | أرامكو (@Saudi_Aramco) July 18, 2018

Again, despite clear injury to Saudi Arabia’s Aramco oil refinery, the Houthis failed to publish any evidence on drone usage in this claimed attack — and one can conclude that this was possible a propaganda effort, designed to drive fear into parties to the conflict.

Analysis & Conclusion

Based on the open sources available, it is highly likely that a Houthi-led drone attack did not take place in Abu Dhabi or Dubai. Propaganda usage in the form of infographics, pictures and statements by Houthi leaders were pronounced following each claim, following a propaganda pattern. Yet parties to the conflict should not ignore the potential threat, and here is why:

On April 11 of this year, Saudi Arabia’s air defence systems downed two Houthi drones in Abha International Airport and Jizan, southwest of Saudi Arabia.

According to the Saudi-led coalition’s spokesman, Colonel Turki Al-Maliki, an “unidentified body” was flying towards Abha International Airport at 7:40 a.m. Saudi local time. The object was destroyed by air defence systems, the remnants alleged to be those of a Houthi drone. On the same day in Jizan, the Saudi defence claimed to have destroyed another Houthi drone. According to Al-Maliki, the drone was identical to the remnants of the one downed at Abha International Airport. The incidents show that, at the very least, the Houthis do possess enough drone capability to enter Saudi Arabia.

A growing risk to the Saud-led coalition’s aviation and hydrocarbon industry exists, as seen with Houthi ballistic missile attacks in Saudi Arabia. This includes international companies operating in coalition countries and using maritime lanes in the Red Sea’s Bab Al Mandeb water straight. Despite there being an investigative question over Houthi drone use beyond Yemen’s borders and into the UAE, Houthi ballistic missiles have already caused casualties – killing three civilians in Saudi Arabia in June 2018.

Last month, the Houthis published for the first time a recorded drone live-feed of an artillery attack targeting Saudi-led coalition backed forces in the west coast of Yemen.

Here is a screenshot of the attack (source: OSINT):

This demonstrates Houthi capabilities when it comes to recording asymmetric attacks – and makes the alleged high profile attacks against the UAE even more questionable, while also raising the question as to why no such recording was posted after the attack on Saudi Arabia.

The Houthi group’s stated asymmetric strategy is to disrupt the Saudi- led coalition’s economy versus large scale attacks in comparison to other non-state armed groups in Yemen. It could be reasonable to assume that Houthi drones are thus used for DBIED attacks, which wealthy Gulf states would be reluctant to admit intruded upon their airspace — especially when it comes to threats to international airport terminals — hence making it difficult to access available open source evidence for interrogation and verification.

Ultimately, parties to the conflict must take these threats seriously, as the Houthi weapons capabilities continue to grow — increasing the sophistication of potential asymmetric attacks amid an ongoing conflict that’s currently at a stalemate.