Olive Branch Military Outpost Built Atop Afrin Cemetery

Since the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) and allied Syrian Arab and Turkmen militias concluded “Operation Olive Branch” in Syria in late March of 2018, allegations of human rights abuses have widely circulated on social media.

Among these charges is the destruction of graveyards and accompanying shrines throughout Afrin. Videos and photographs have surfaced depicting Yezidi religious shrines looted and vandalised, as well as a cemetery housing of fallen People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) fighters being destroyed with construction equipment.

Using publicly available satellite imagery and photographs taken on the ground, we have examined one such case near the town of Anqele in Afrin. Following the town’s capture by TSK and allied Syrian opposition groups, a hilltop military position was constructed on top of a local shrine as well as portions of a cemetery (located here). The Ali Dada shrine was completely leveled, while numerous graves have disappeared underneath the recently moved dirt. Months afterwards, this occurrence was reported on by local media activists in Arabic and in English. Like many such allegations and reports, it did not receive wider attention.

A communal meal being eaten on the hilltop near Ali Dada shrine in 2014 (source).

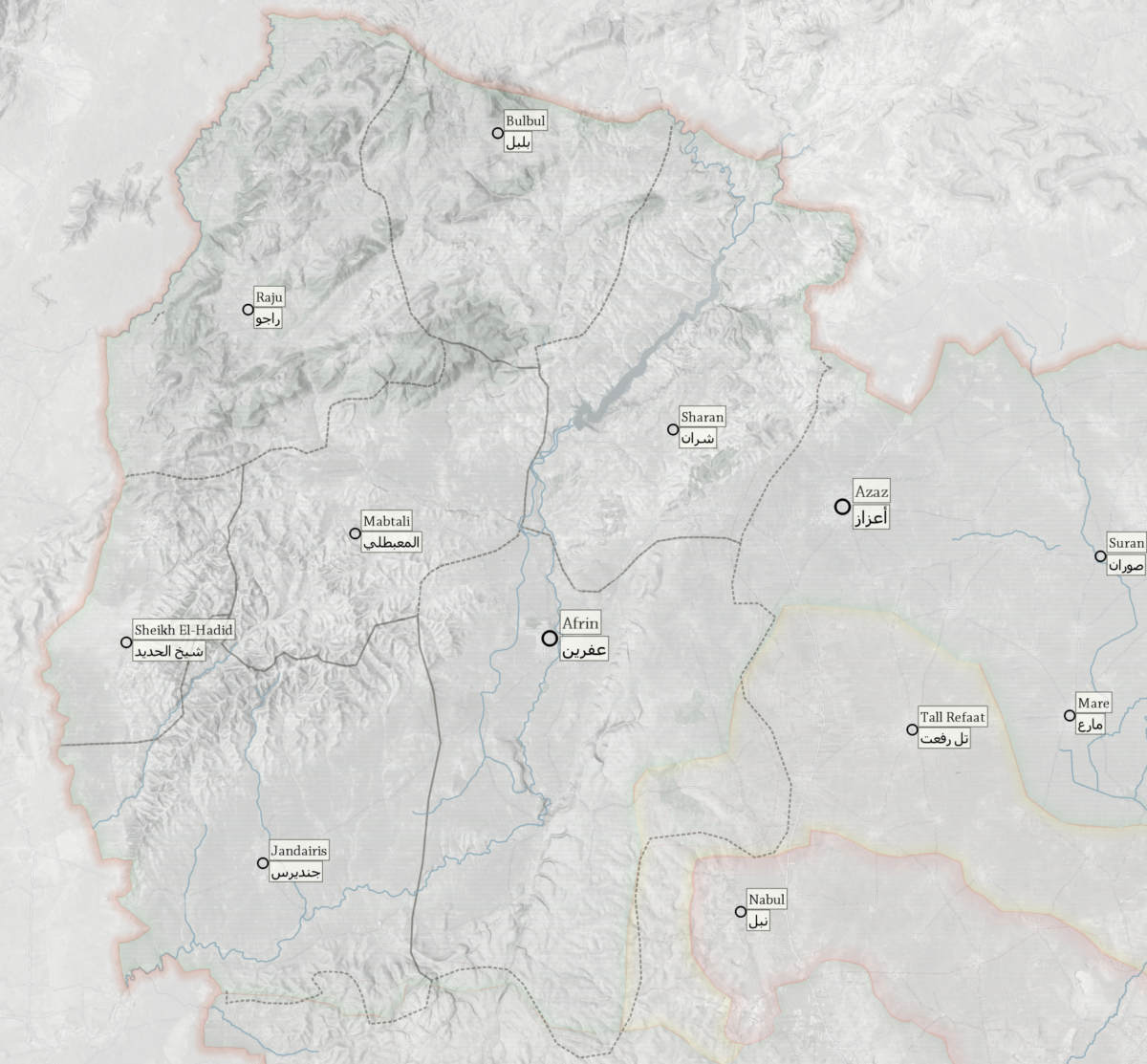

Anqele is situated in the Sheikh al-Hadid subdistrict of Afrin and sits on hilly terrain overlooking Syria’s western border with Turkey. It is adjoined in the north to the town of Senare, while the graveyard and shrine in question lie on a hilltop to the east. The hilltop is elevated approximately 60 meters above the town and 90 meters higher than the small valley further east, making it a natural vantage point over the surrounding area. On the other side lies a forested ridge which reaches out toward Afrin city. This portion of the countryside to the west had seen no combat prior to 2018 and, likely due to its relative low elevation and proximity to the Turkish border, had not been fortified by the YPG.

Anqele and Senare as seen from the west, with the cemetery hilltop marked with a red pin (source: Google Earth/DigitalGlobe).

The two towns were taken on February 26, 2018, a month into Operation Olive Branch, and were among the last YPG-held towns along on the border. Judging by rebel media focused on related topics, Anqele and Senare were seized with little to no resistance. The towns were also largely empty as most the inhabitants appear to have fled east, first to other parts of Afrin and then on to the Shahba region north of Aleppo city.

The factions that broadcasted their involvement in its capture were the Syrian National Army’s First Legion, a loose configuration largely made up of ethnically Turkmen groups, and Liwa al-Vaqqas, a small, relatively unknown newcomer faction. Judging by its symbology and the use of Turkish in their name and logo, Liwa al-Vaqqas is presumably made up of Turkmen as well. Such groups often enjoy close ties to Turkey from where they receive military support and training.

Soon after the capture of the towns, two fortified military positions were constructed, the aforementioned one to the east, and a less developed one on a hill just west of the towns. The frontline to the east was not to move until mid-March, after Turkey and their allies captured Afrin city and then quickly captured the encircled rest of the district. Since then, not much news has come out of Anqele and Senare, perhaps due to their small populations and relatively isolated location. Pro-Kurdish media has reported that Liwa al-Vaqqas was in control of the town as of late June 2018.

1st Legion fighters in Senare, on February 27, 2018 (source, approximate location).

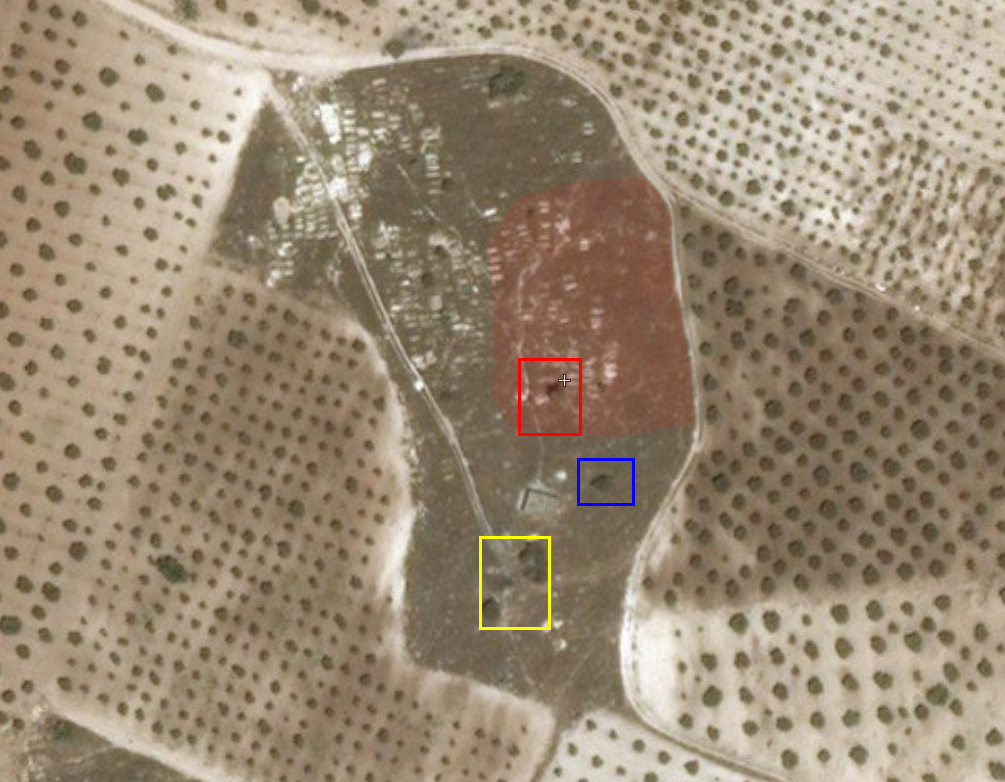

The construction of this military position to the east of Angele took place between the town capture and March 5, 2018, satellite imagery courtesy of Planet shows.

The military position stretches a little over 100 meters north to south, and is approximately 45 meters at its widest. The position has housed several military vehicles and structures since its construction.

The Turkish Armed Forces’ military position on top of a hill. The initial construction of March 2018 is marked in red, and further addition is marked in purple (analysis: Bellingcat, source: Google Earth/DigitalGlobe).

Between April 12 and 14, the military position expanded towards the southwest and new vehicle paths emerged on the western side of the hill. Its size has remained static since then.

Many similar fortifications were built in non-urban areas of Afrin during Operation Olive Branch, including one a kilometer west, located here. However, since the formal end to hostilities, many of these have been abandoned in favor of larger, more fortified bases within Afrin’s larger towns.

News of the above-mentioned incident first appeared April 9, 2018, on a Facebook page run by locals of Senare reporting on the area. This corresponds with when many of the town’s inhabitants began returning.

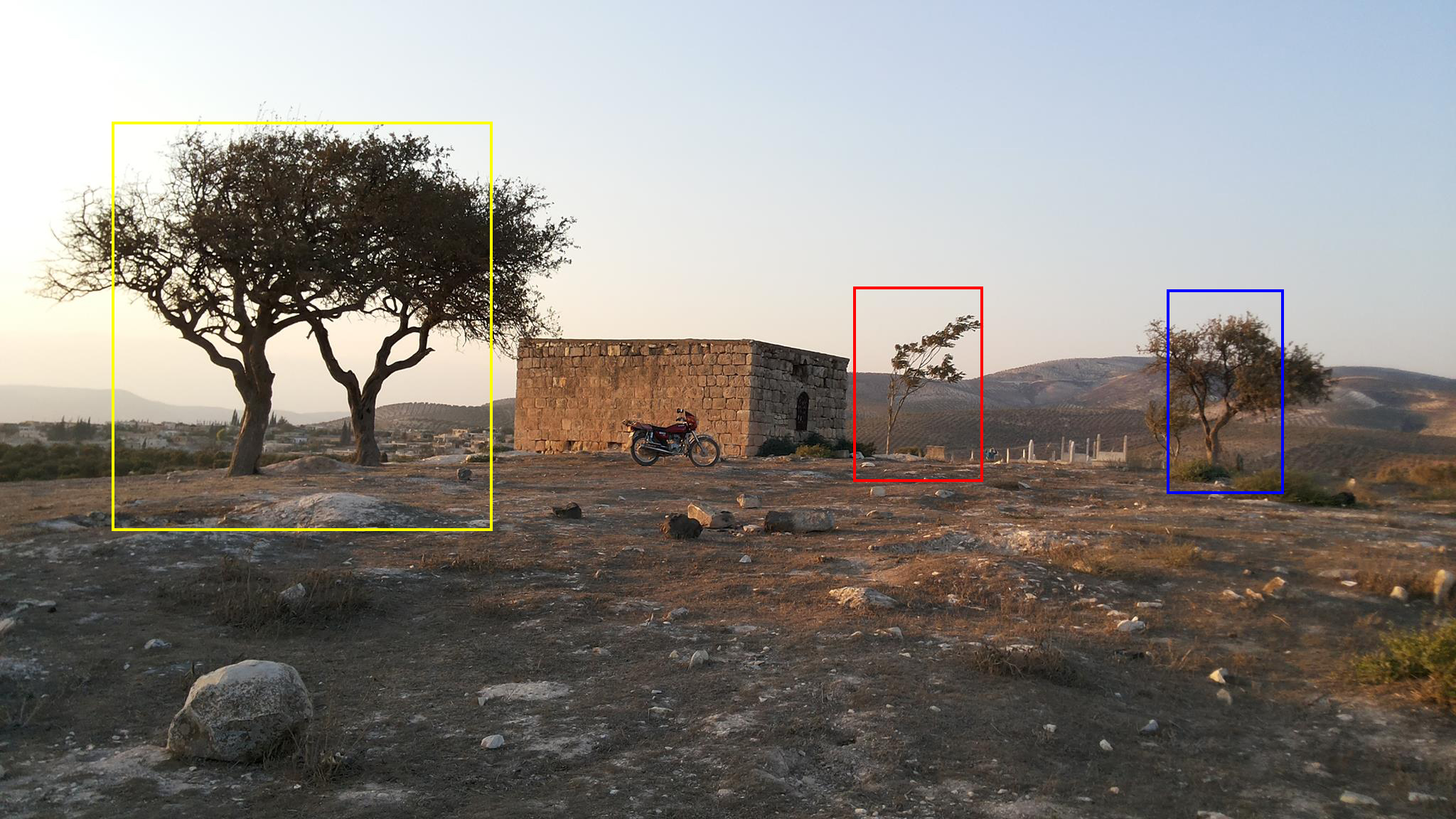

During the same week the page Senare Town News was posting videos from locals entering their homes for the first time since late February and finding them looted. A picture referred to as “Ali Dada’s graves” was posted of the hilltop in the distance, in which one can make out the defensive berms. One can make out the trees located within the cemetery in front of the position, meaning the picture was taken from the north, most likely in Senare itself.

Another local Facebook page posted two images of the fortification on May 3, 2018, taken from the west, in Anqele. One offers a much clearer view of the hill, while the other is from a slightly different angle and more zoomed in. The caption, however, does not make reference to the obvious changes that have occurred to the hilltop and its shrine. Due to the visibility of the more recent path down the hill, at some point after April 13 or 14 was when the expansion of the position occurred.

Image of the hilltop taken from a distance, pointing out the cemetery, posted on April 9, 2018:

One of the images from May 3, 2018. Note the new path, visible on the right edge:

It was not until mid-June 2018 that more detailed reports began circulating in Afrin-focused media activist circles. Such reports mention the destruction of the Ali Dada shrine, as well as numerous graves being disturbed. These accounts mention 500 or more graves as being destroyed, however that may likely be an embellishment, mainly due to the lack of more recent photographs from the site itself.

The Ali Dada shrine appears to be the small rectangular building on the southern end of the property. According to local reports, the shrine was 250 years old and contained a grave dating back to the 17th century. One can see both through satellite imagery and the photos taken since construction that the shrine, as well as the trees to the south of it, has been leveled.

Photo of the hilltop from March 2016 (source).

Same photo from May 3, 2018, image overlaid.

The damage done to the cemetery itself is not as extensive. Most of the graves are located in the northwestern corner of the property, below the hilltop. It is unclear exactly how many of plots are now buried under the fortification.

However, when comparing the before and after satellite footage, we can see that approximately a third of the graveyard has disappeared. This eastern uphill portion is less densely filled than the rest, but a significant amount of the plots have been destroyed (source):

More here (source):

Analysis: Bellingcat, source: Wikipedia.

In the months since Operation Olive Branch ended, locals as well as international monitors continue to report, on the troubling human rights situation within Aleppo’s Afrin district. This case is just just one example of the destruction of graveyards and shrines local to the area. Further open source investigation and documentation of such reports is required in order to fully understand the scope of what is being done to Afrin.

Bellingcat’s research for this publication was supported by PAX for Peace.