Fuel to the Fire: Satellite Imagery Captures Burning Oil Tanks Libya

Recent eruptions of violence in Libya’s so-called ‘oil cresent’ between armed forces loyal to Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) and rival armed groups resulted in another row of burning oil tanks. In the areas around oil terminals at Es Sider and Ras Lanuf, clashes continued for days. As a result of the shelling, various oil tanks at the Fida Oil Farm, west of the Ras Lanuf oil terminal were hit and caught fire. These clashed demonstrates the dangers associated with fighting in and nearby industrial facilities storing large quanitities of potential hazardous substances and the wider risks associated with a chemical incident in armed conflicts. This blog will provide a brief outline on open-source reporting and satellite imagery from the area and a brief background the ongoing targeting of the oil infrastructure in Libya and their associated wider socio-economic and environmental consequences.

First attack on Ras Lanuf

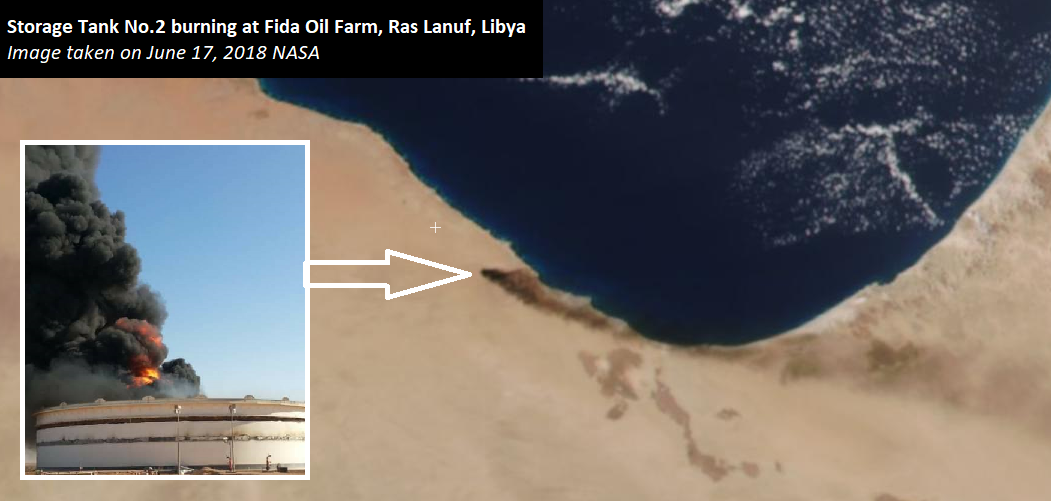

On Thursday June 14, oil tanker nr. 2 at the Fida oil farm was reported burning, first mentioned on social media and later confirmed through geo-location.

Clashes continue near al-Sidrah amid reports that an oil storage tank was hit by a shell said to have been fired by 'Benghazi Defence Brigades' and Ibrahim Jathran’s tribal fighters. #Libya pic.twitter.com/5dtzZWPEC6

— The Libya Times (@thelibyatimes) June 14, 2018

Geolocated the image of burning oil: it's taken from the housing area north of Ras Lanuf oil facility, confirming it's not As Sidra. pic.twitter.com/JKJRp5TH1K

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) June 14, 2018

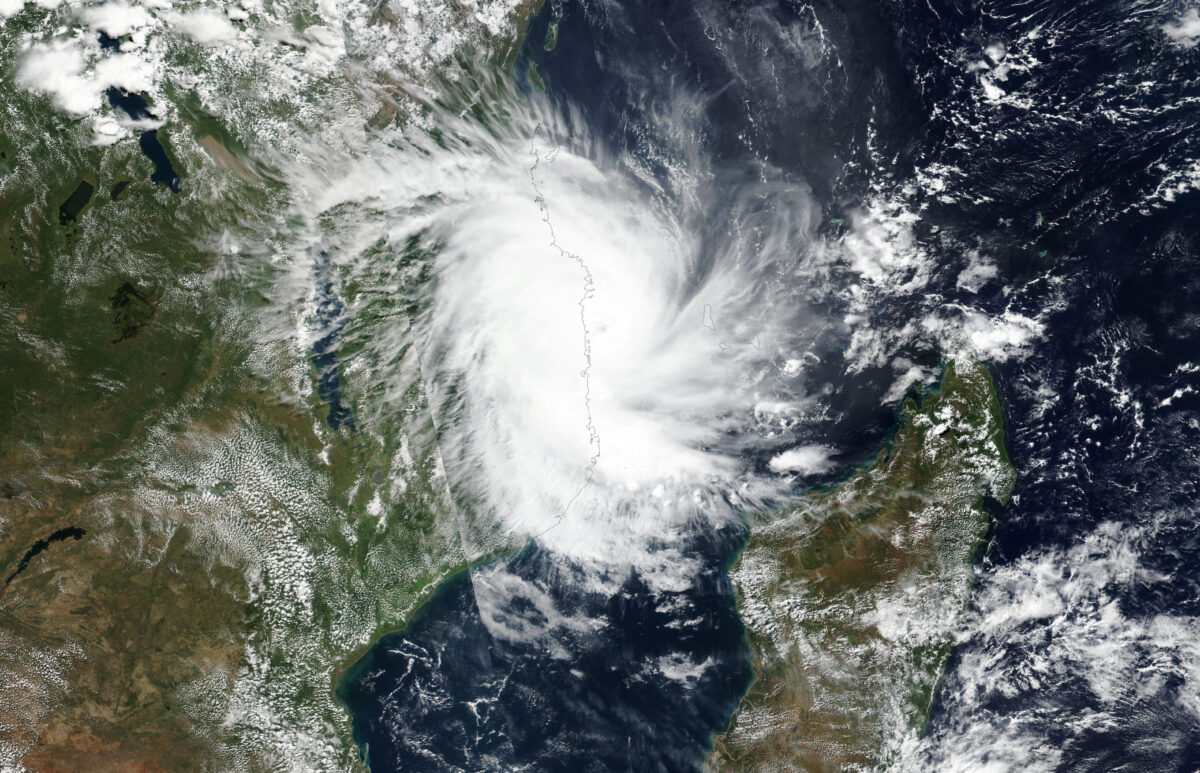

This was also later confirmed with NASA and ESA Sentinel 2 imagery.

Ras Lanuf it is! Image just arrived from NASA. cc: @wammezz #OOTT #Libya #@@NOC_Libya pic.twitter.com/VtfoX0qnMN

— TankerTrackers.com? (@TankerTrackers) June 14, 2018

Libya’s National Oil Corporation put out a warning for a looming ‘environmental disaster’, as the fire threatened nearby oil storages, and lacked sufficient resources to contain the fire. The facility has the capacity to store over 980.000 barrels of crude oil. Images were put online by the NOC, showing the destruction at the storage facility from the initial shelling.

Images showing Al-Harouj oil storage tanks today as clashes between #BDB/ Jathran & #LNA Forces continue in #RasLanouf. Oil tanks are being destroyed almost every year in #Libya since 2014 thus damaging the already ailing economy. pic.twitter.com/AtaEYBMyWd

— Nadia Ramadan (@NadiaR_LY) June 16, 2018

Second strike

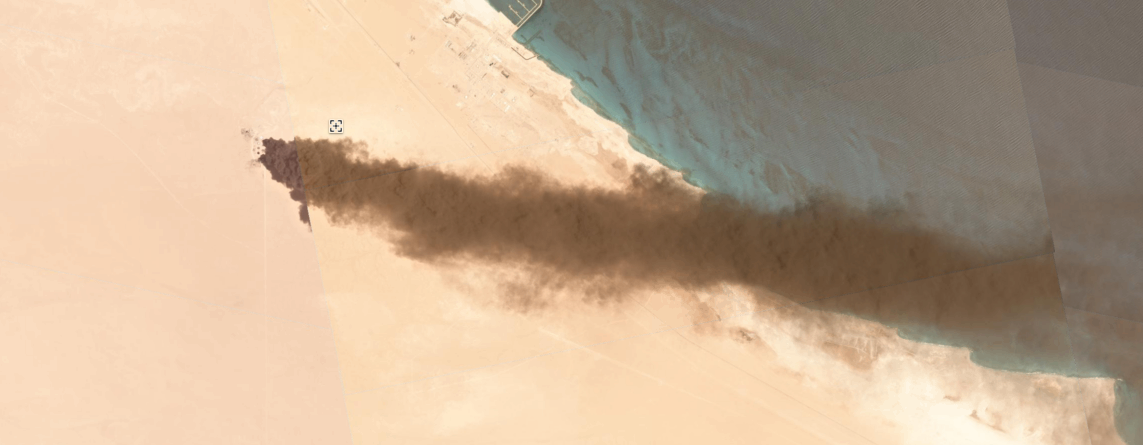

On Sunday June 17, another attack resulted in Tanker No.12 catching fire. Satellite imagery from NASA and Planet Labs captured the burning oil tank.

Planet Labs imagery from June 17, 2018 showed the intensity of the firesat the Fida oil farm and the wider smokeplume heading eastwards.

In statement put on on Monday June 18, the NOC warned of spread of the fires to nearby oil storage tanks.

Catastrophic damage at #RasLanuf terminal https://t.co/5O3yFxOVdu pic.twitter.com/1A24niNBjk

— National Oil Corporation المؤسسة الوطنية للنفط (@NOC_Libya) June 18, 2018

This overview by Twitter User @mazighie provides an overview of the oil tanks conditions at the Fida farm that have been damaged in previous attacks and the ones that are currently burning

#Libya Ras Lanuf tank blazes#Status

1⃣ Ok.

2⃣ Burning?

3⃣ Ok

4⃣ Completely burnt

5⃣ Partially burnt

6⃣ Ok.

7⃣ Under construction

8⃣ Collapsed

9⃣ Partially burnt

? Ok.

1⃣1⃣ Completely burnt

1⃣2⃣ Burning?

1⃣3⃣ Collapsed

Aerial image dated 2017 via @TankerTrackers pic.twitter.com/d1QtMCc98a— Khaled Butou (@mazighie) June 17, 2018

Repeated targeting of oil infrastructure in Libya

Oil facilities have been targeted on multiple occasions during the ongoing conflict by a number of warring parties. In particular the so-called Islamic State had an appetite for destruction, and ordered direct attacks against oil facilities, as analysed in our previous Bellingcat article from 2016. Various attacks have taking place in 2017 and 2018 against oil pipelines coming from the south towards the Es Sider oil storages

As demonstated using open-source data on ship movements by Tankertrackers, the facilities at Ras Lanuf and Es Sider are an important oil hub for Libya’s oil exports.

Home to light sweet oil, Ras Lanuf exports have lately gone mostly to Italy but also UK and even Australia! Libya is definitely one of the main reasons why southbound Suez Canal crude oil traffic has picked up over the past year in particular. #OOTT pic.twitter.com/1GRPM6jtht

— TankerTrackers.com? (@TankerTrackers) June 14, 2018

Environmental damage and health risks

Apart from the economic damage, as the country lacks income from oil revenues, there have been repeated concerns over the wider environmental health risks caused by the destruction of oil facilities. Burning crude oil tanks and attacks on pipelines could have larger environmental risks for nearby communities and the fragile ecosystem.

Oil fires release harmful substances into the air – including sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and lead. These can be transported over a large area before deposition in soils, potentially causing severe short-term health effects for people and wildlife, especially people with pre-existing respiratory problems. Damage to oil storage sites and processing facilities can lead to the release of a range of dangerous substances. Groundwater contamination can threaten agricultural land and the people who rely on ground and surface water for irrigation, drinking, and domestic purposes. Long-term exposure to hydrocarbon pollutants may lead to respiratory disorders, liver problems, kidney disorders and cancer.

This reflects the wider problems caused by conflict-pollution, and these concerns have been addressed in last year’s UN Environmental Assembly’s resolution on conflict pollution, calling for States to provide support to the relevant Libyan authorities with assessing and cleaning-up pollution at these location and ensure protection to prevent and mitigate further risks to the environment and human health.

Bellingcat’s research for this publication was supported by PAX for Peace.