Seven Years of War — Documenting Syrian Rebel Use of Anti-Tank Guided Missiles

Written in cooperation with @SCW_Nuggie.

Over the course of seven years of war, Syrian rebels have been fighting an army that once had the 6th largest number of tanks in the world. This article will detail the collection of footage of Syrian rebel anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) use and their impact on events during the Syrian civil war.

Abu Hamza, from Free Syrian Army’s 1st Coastal Division, operating a TOW in early 2015. Famed for his skills in operating the BGM-71 TOW.

General Information about ATGMs in the Syrian Civil War

At the start of Syrian Civil War, the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) had stockpiled a large amount of both armoured vehicles and anti-tank weapons in case of war with Israel. These weapons and ammo were accumulated over several decades and spread throughout many army bases across Syria. While this protected them from potential Israeli preemptive strike, many of these bases were indefensible in case of civil war. (For more information, the “The Syrian Army: Doctrinal Order of Battle” report by the Institute for the Study of War is an excellent resource.) Syrian rebels also over time obtained significant numbers of anti-tank weapons from sympathetic foreign nations.

Most of the ATGMs in the SAA arsenal at the start of the Syrian civil war were of Russian/Soviet origin. Because the SAA has historically been a conscript based army and due to constant preparations for a war with Israel, the rebels immediately had access to people who were trained in using various ATGMs found in the SAA arsenal. This talent pool was further increased by the defections of active military personnel.

ATGMs used during the Syrian Civil War:

NATO reporting names are mentioned between brackets

- 9K11 Malyutka (AT-3 Sagger) — The Manual Command to Line Of Sight (MCLOS) wire-guided Anti-Tank Guided Missile (ATGM) system was developed in the Soviet Union and was the first man-portable anti-tank guided missile of the Soviet Union. It requires considerable training and practice to master since even a minor disruption in the gunner’s concentration would likely cause a miss. Suppressing fire significantly decreases the chance of hitting the target. Effective firing range: 500–3 000 m.

- 9K111 Fagot (AT-4 Spigot) — A Second-Generation Tube-Launched SACLOS wire-guided Anti-Tank missile system of the Soviet Union for use from ground or vehicle mounts. Effective firing range: 70–2 500 m.

9K113 Konkurs missile system (launcher and missile) and a 9M111M Faktoriya missile in the launch tube (standing).

- 9M113 Konkurs (AT-5 Spandrel) — a SACLOS wire-guided anti-tank missile of the Soviet Union. This is the most common ATGM in the Syrian arsenal. The 9K113 Konkurs uses the same launcher as the 9K111 Fagot which simplifies their use by rebels because of the shared ATGM launcher. Effective firing range: 70–4 000 m.

- 9K115 Metis (AT-7 Saxhorn) — a SACLOS wire-guided anti-tank missile of the Soviet Union. Effective firing range: 40–1 000 m.

- 9K115-2 Metis-M (AT-13 Saxhorn-2) — a Russian SACLOS wire-guided anti-tank missile. It uses the same launcher as 9K115 Metis. Effective firing range: 80–2 000 m.

Kornet prepared to be fired at landing Mi-17 Helicopter at Abu Duhur Air Base on 12 September 2014.

- 9M133 Kornet (AT-14 Spriggan) — a modern Russian laser-guided SACLOS anti-tank missile. It is the most powerful ATGM operated by the Syrian Arab Army. Effective firing range: 100–5 500 m.

A TOW missile on display at the White Sands Missile Range Museum, a United States Army military testing area in New Mexico. Photo via their website.

- BGM-71E TOW (“Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wire-guided”) — An American second generation ATGM. The launcher can be equipped with infrared cameras for night time use. Almost all TOW missiles that Syrian rebels obtained were TOW-2A variant, which is optimized to defeat reactive armor with tandem warheads. Effective firing range: 65–3 750 m.

Collecting Visual Evidence

As most of Bellingcat’s readers are likely aware, YouTube and other video and/or photo hosting websites have deleted countless footage related to the Syrian civil war as part of a broader effort to delete extremist content on their servers. Between false positives and malicious use of reporting content by supporters of all sides of Syrian civil war, this effort has resulted in many photos and videos being lost forever.

Nevertheless, YouTube is still the main source of visual evidence that has been collected for this database. The author has archived footage from the Syrian civil war since Spring 2015, mostly focused on documenting rebel ATGM use.

Another important source information has been the page regularly updated by Twitter user @yarinah1 which contains descriptions and links to videos for rebel ATGM launches since early 2015.

All of this and other sources have resulted in an archive worth of 105 gigabytes of data in 3,971 files, 85% of which are videos exceeding 100 hours of war footage.

The author would like to point out that monitoring ATGM shots based on visual evidence is much harder than counting armoured vehicle losses because cameras are not always present with ATGM teams. Videos documenting ATGM launches were only published more often after the first TOW-2 shipments, perhaps due to its propaganda value. This specific issue will be discussed later on.

As mentioned above, this article only includes ATGM launches by Syrian rebel groups and excludes such launches by the Syrian Democratic Forces and the YPG, as well as the so-called Islamic State (IS) not included.

Having discussed the methodology, the documented Syrian rebel ATGM launches will now be presented and discussed per year.

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2011

No ATGM launches have been documented in 2011, highly likely because of the lack of sophisticated weaponry in the infancy of the uprising.

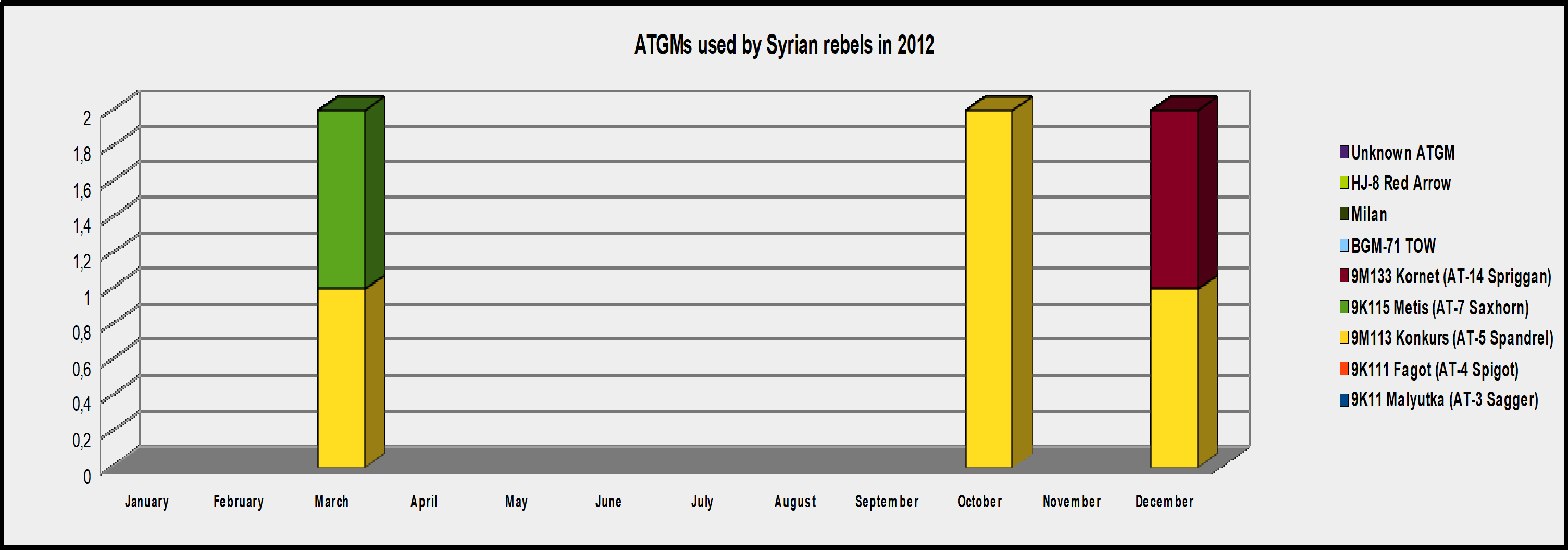

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2012

ATGM footage in 2012 was still very rare despite the fact that pro-government forces suffered 478 documented losses of armoured vehicles that year. While reports of ATGM use appeared from time to time, in most cases they lacked visual evidence. Based on the review of combat footage from 2012 it appears that before firm frontlines were established pro-government losses were mainly caused by RPGs, recoilless rifles, and other unguided weapons when rebels overran pro-government positions or ambushed army convoys. The total count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches for 2012 is just 9.

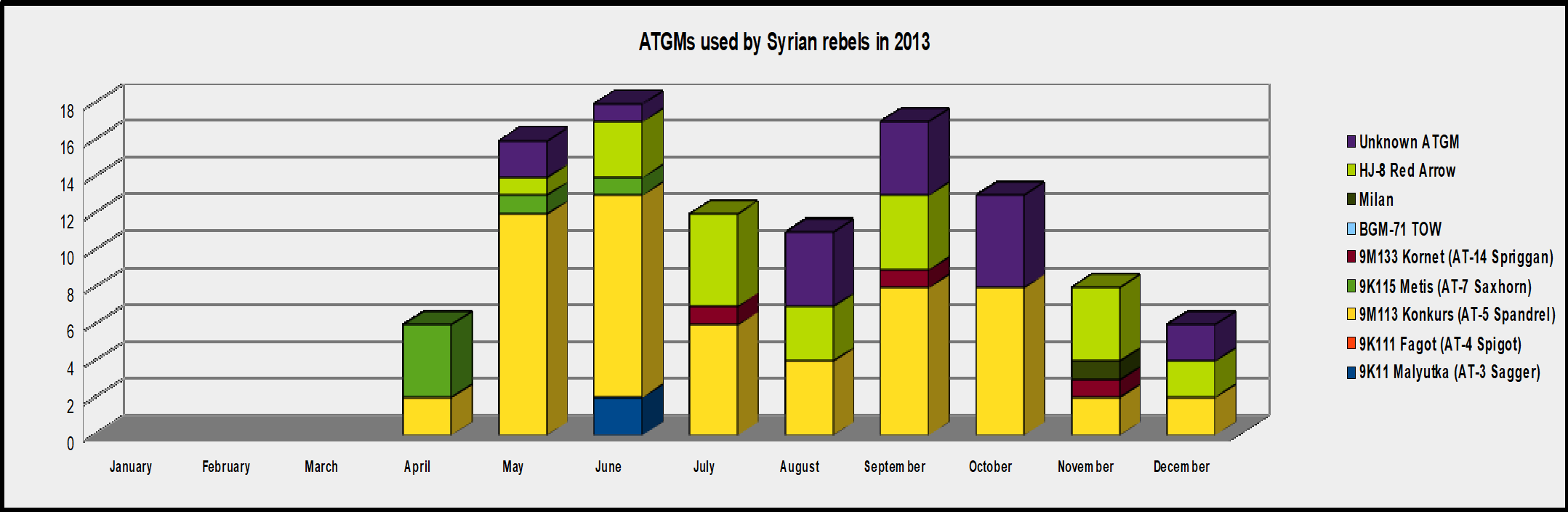

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2013

As the Syrian civil war progressed into a more conventional conflict with clear frontlines ATGMs became more important to rebels. The rebels managed to obtain a large quantity of ATGMs by overrunning government bases stockpiled with copious weaponry however the recording of ATGM launches was still not standardized.

Below is one example of a captured ATGM storage in the Eastern Qalamoun area in the Damascus governorate where rebels obtained approximately 200 ATGMs.

The total count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches for 2013 is 257.

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2014

A major change happened in terms of United States (U.S.) policy in early 2014 allowing the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to distribute TOW ATGMs supplied by U.S. allies in the region to vetted Syrian rebel groups. Because the U.S. tried to avoid issues with a large quantity of supplied weapons being transferred to third parties, they made a decision to demand a video to be filmed of the preparation and launch of each supplied ATGM. Only after supplying this evidence would rebels receive new missiles. Another decision was that rebels would get mostly TOW 2A missiles (with the rest being ex-Soviet ATGMs), which are powerful enough to destroy any armour in the Assad regime’s arsenal while also not posing a risk of technology transfer to U.S. enemies.

The U.S. stipulation regarding TOW launch footage made tracking rebel use of these ATGMs much easier since most groups decided that since the video has to be made anyway, they also released it as a propaganda tool. Since these videos turned out to be quite popular (several rebel groups and their TOW gunners became quite famous for their skill), a higher portion of other ATGM strikes started to be filmed as well even for missiles that were sourced locally.

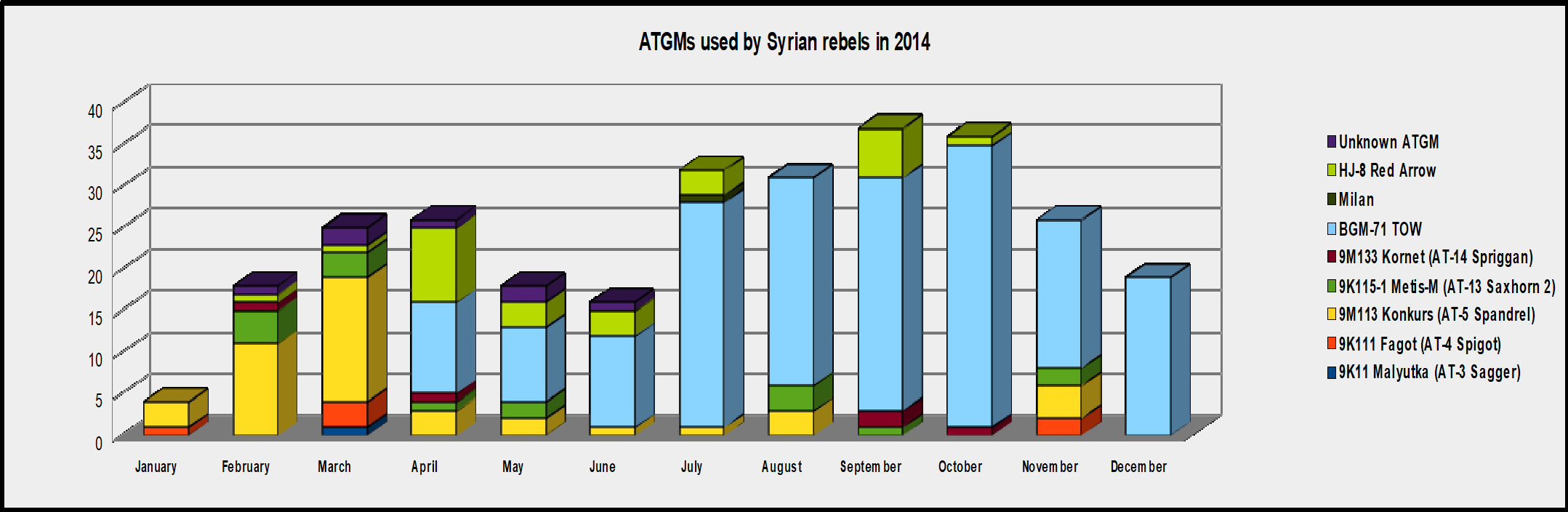

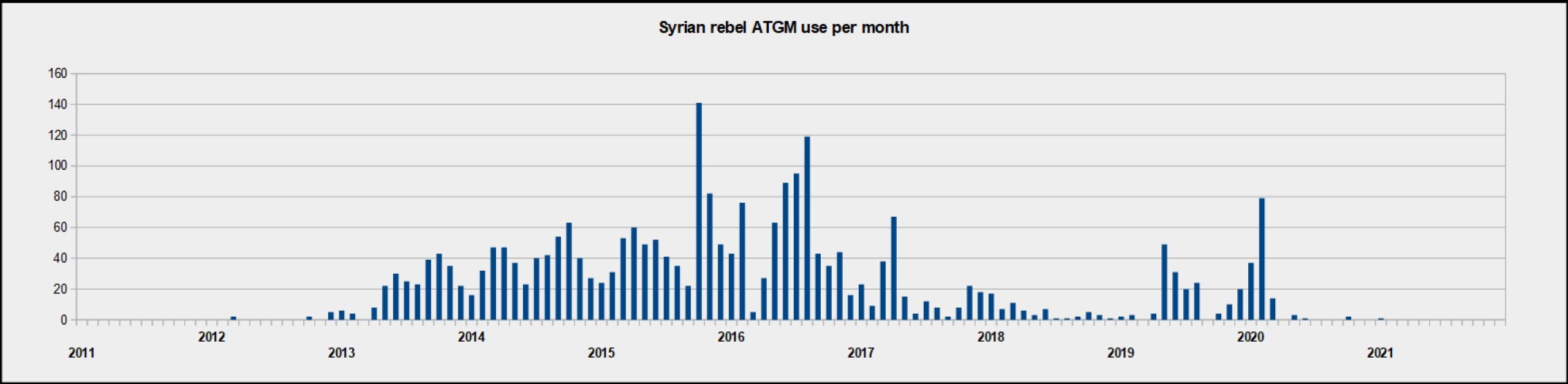

As seen on the graph above, the number of fired TOW ATGMs rose gradually — this is both due to the gradual increase in U.S.-supplied missiles as well as the increasing number of trained TOW crews (training itself happened in rebel-friendly Gulf Cooperation Council countries).

The first documented use of TOW ATGM by Syrian rebels is from 1 April 2014 by the Harakat Hazzm group.

For those interested in Syrian rebel groups (including info on which ones were authorized users of TOW ATGMs), reading the Bellingcat article “Syrian Opposition Factions in the Syrian Civil War” is recommended.

Captured T-62 tanks by opposition forces at the Wadi Deif base in the Idlib governorate on 15 December 2014.

The shipments of TOW ATGMs helped rebels bolster their defenses which were weakened due to heavy fighting with ISIS and by the end of 2014 TOWs provided a significant help in a takeover of several government bases – most notably the Wadi Deif base in Idlib.

The total count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches for 2014 is 468.

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2015

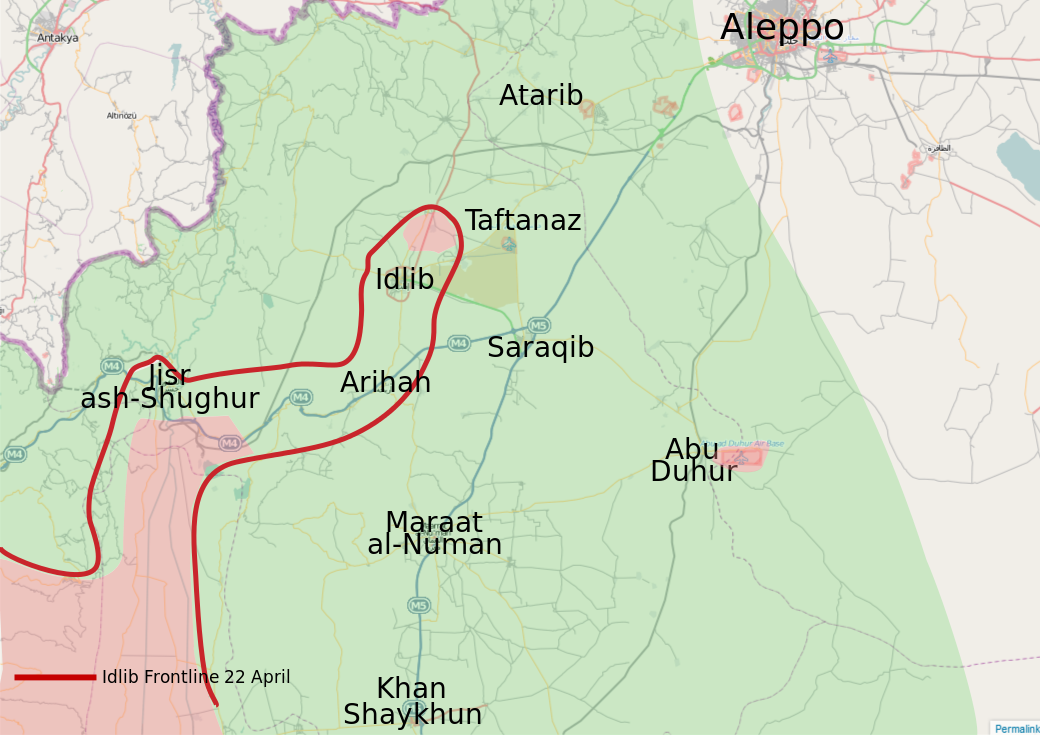

In early 2015, rebels formed an alliance of a large number of various ideological groups (from moderate FSA units to Jabhat al Nusra) called Jaysh al Fatah. This allowed the rebels to combine resources and various specializations which allowed the rebels to start a large offensive in the Idlib governate using combined arms operations. TOWs and other ATGMs eliminated a significant number of tanks that the government forces had in exposed defensive positions and defeated the pro-Assad usual tank-heavy counterattacks, allowing rebel infantry and artillery to attack and hold weakened positions. At the start of the rebel offensive, the government forces held onto a fairly long, exposed salient which allowed Jaysh al Fatah to effectively turn any pro-government movement inside the salient into a loss of material and manpower.

Map of territory changes in Idlib governate during the rebel offensive during Spring 2015. Map by Alhanuty via Wikipedia.

In late April, Jaysh al Fatah besieged around 250 pro-government troops in the Jisr al Shughour hospital prompting Assad to appear on TV promising to lift the siege. Despite moving a significant amount of troops and heavy weapons (primarily from eastern Homs) all attempts to lift the siege failed with heavy losses. Part of the failure can be contributed to the surrounding ideal for ATGMs – forested hills rising high above the plain left any government attempt to advance exposed to ATGM teams.

View on the Ghab plain from a nearby hill. The villages of Ghaniyah, Kufayr, Frikka, and Al-Sirmaniyah are clearly visible. Source: Eyad Alhosain.

When pro-government forces were unable to break the siege and defenders became desperate they launched a breakout towards their positions which only 10-15% survived.

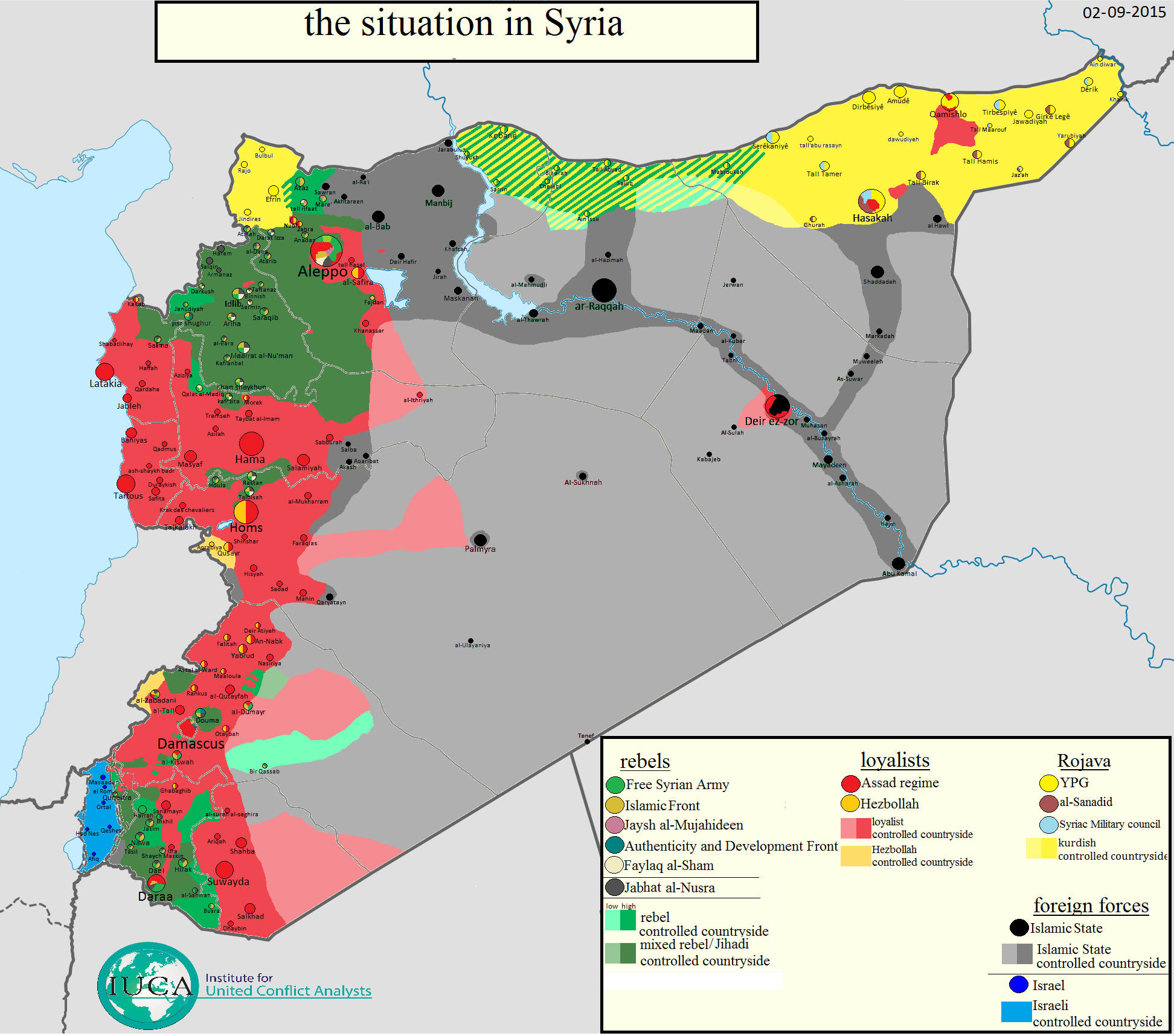

Part of the pro-Assad forces’ response to defeats in Idlib was to move its last half-decent units from the eastern Homs governorate. ISIS, quick to exploit a weak enemy frontline, exploited this to launch at first localized attacks around Sukhnah. Due to better than expected results, this localized attack became a proper offensive leading to the rather quick fall of Palmyra and the area around it.

In late summer, while the pro-Assad forces managed to defeat the FSA‘s Southern Front long announced Daraa offensive, they were bleeding manpower and equipment on multiple fronts. Jaysh al Fatah not only captured the besieged Abu Duhur Air Base and made progress in Latakia, but also started preparations for a large-scale offensive aiming to capture the Hama governorate. This would not only result in a large loss of valuable territory, but it would also come close to splitting the pro-government forces into three areas: Aleppo, Damascus plus southern Homs and the coastal areas.

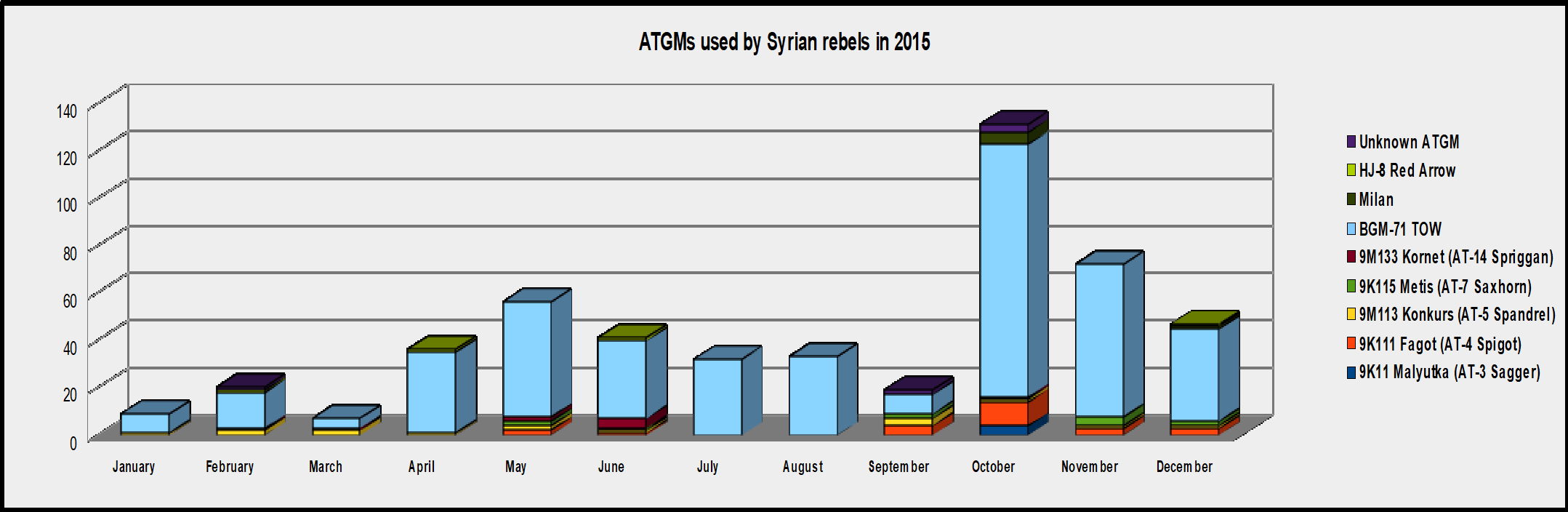

Shortly after Jaysh al Fatah’s victories in Idlib, Russia decided to intervene on behalf of Assad. Russia moved dozens of planes and helicopters to the Khmeimim Airbase in Latakia while Iran moved increasing numbers of military advisors, as well as Iraqi, Afghani, and Hezbollah reinforcements into Syria to stabilize the situation. Emboldened by this increase in support, in October 2015 the SAA started a major offensive to retake northern Hama and advance into the Idlib. This resulted in a major battle against rebels who used around 140 ATGMs in that month alone, inflicting large losses on pro-government armored units and even some territory in northern Hama, notably the town of Morek. However, increasing airstrikes and ground attacks forced the rebels to cancel plans for an immediate Hama offensive.

Another important event to note is the Southern Aleppo offensive in which the Iranian pro-government proxies reached al Eis. A lot of ATGMs were used both against armored vehicles and groups of soldiers to try to stop this offensive.

Rebel positions in Latakia also experienced a large government offensive in late 2015 during which FSA First Coastal Division (well known for its TOW usage) suffered significant losses.

The total count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches for 2015 jumped to 637*.

* Around the time of the Jaysh al Fatah offensive in Idlib, online pro-government supporters started to mass-reports rebel YouTube channels (and other photo/video sharing websites) which resulted in many videos and whole channels being deleted. Since at that time archiving, Syrian Civil War footage wasn’t very common a disproportionate percentage of combat footage has been presumed lost.

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2016

In 2016, thanks to foreign reinforcements provided by Iran, air support from Russia, and small shipments of modern T-72 variants and T-90 tanks, the Syrian government began to slowly start to gain the upper hand in the Syrian Civil War.

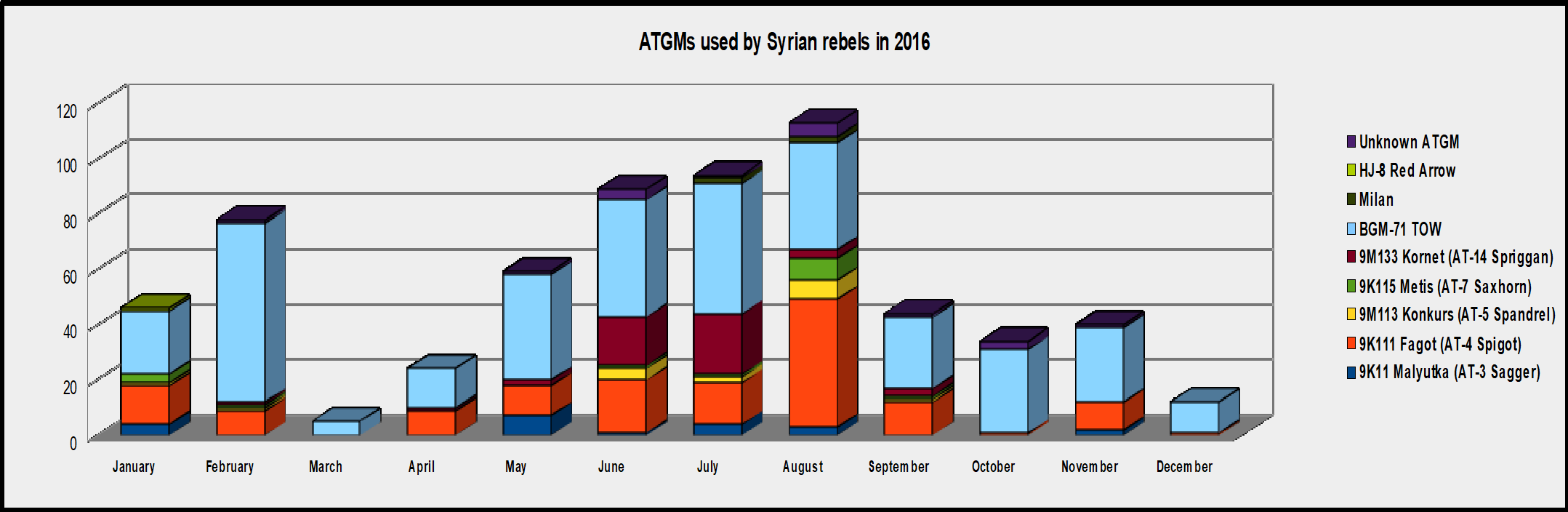

Pro-government offensives resulted in intensive use of ATGMs by rebels, especially around Aleppo city. The government forces first fought to reach the besieged pro-regime towns of Nubl and Zahraa and later pivoted to cut off rebel-held Aleppo City from other rebel territories.

At the same time, rebels launched an offensive to revert territorial gains of Iranian proxies from late 2015 in the south of Aleppo.

Shortly after pro-government forces besieged rebel-held parts of Aleppo, rebels launched a large-scale assault on southern Aleppo centred at the Aleppo Artillery College and surrounding urban areas. This offensive resulted in the lifting of the siege of rebel help parts of Aleppo for a few weeks before the regime managed to recapture this area at a cost.

A notable incident took place in early September 2016, when during rebel advance in northern Hama (which exploited the fact pro-government forces pulled a lot of troops from Hama to Aleppo for its offensives) rebels got close to Hama Airbase and TOW crew from Jaysh al-Izza was able to hit a pro-government Gazelle SA 342 helicopter during its low and slow flight near the frontline.

Video of SyAAF Gazelle being shot down by a BGM-71 TOW pic.twitter.com/DKPYmREJjr

— BM-27 Uragan (@bm27_uragan) September 2, 2016

Around this time rebels also received a new supply of Soviet model ATGMs (mostly 9K111 Fagot (AT-4 Spigot)) in addition to their now regular shipments of TOWs.

Drone footage of a failed pro-government assault on the Artillery Faculty, at the time held by Jaysh al-Fatah, in southern Aleppo, 28 August 2016.

By the end of 2016, forces loyal to Assad captured all of the rebel-held parts of Aleppo City. However, all those months of heavy fighting resulted in significant losses for both sides and rebel ATGM use was critical in defeating many pro-government assaults and delaying their advance. During high-intensity fighting sometimes 10+ ATGMs were used by rebels per day.

T-90 tank after it was hit 2016.02.26 at Sheikh Aqeel, northeastern Aleppo, by a TOW ATGM. The left side of the tank, which was hit, is not shown in this photo.

In these intense battles, the TOW 2A encountered T-90 tanks that Russia provided to some pro-government units for the first time. This became the first government tank that was able to withstand a hit from TOW 2A warhead, at least from some angles, which was demonstrated in at least three cases where it remained operational despite a TOW ATGM hit.

Drone footage of disabled or destroyed T-90 after it was hit by TOW ATGM near El Eis in the Aleppo governorate, 10 May 2016.

At the same time, poor training of pro-government units and some luck resulted in two damaged T-90 tanks to be captured (and later used) by Jabhat Fateh al-Sham. At least one T-90 was disabled or destroyed when a TOW penetrated its side armor and was abandoned by its crew in an area that was later lost to rebel advance. Three other tanks that were destroyed by TOW ATGMs were suspected to be T-90s, but due to the long distance from those vehicles, identification was not conclusive. (The T-90 is an evolution of the T-72, so from a long distance it is hard to distinguish from a T-72 unless the Shtora jammer is visible).

Realizing the effect of rebel ATGMs on their armour, the pro-government forces attempted to create it’s own ATGM defeating devices. In early 2016, the Sarab-1 (Mirage) jammer was introduced on some pro-government-operated tanks (it was also rarely seen on other vehicles). It was followed by the Sarab-2 at the end of 2016 and Sarab-3 in 2017. All variants of the Sarab system are using powerful infrared lights in an attempt to disrupt TOW ATGM guidance. This system is mostly ineffective because it has no means of detecting incoming ATGMs and is unable to operate for a significant amount of time. Despite being introduced 2 years ago, the Sarab systems have not been widely deployed on pro-government tanks – most likely due to its poor results.

T-72M1s, one with a Sarab-2 APS, and a slat armored T-72 in Harasta, Damascus, on 29 January 2018. Source: RT via Jason Jones.

What turned out to be a far more effective way of fighting rebel ATGM teams was deploying a large number of its own ATGM teams with spotters on fronts where rebels had active ATGM crews. For this purpose, the pro-government mostly used Kornet ATGMs that had superior range compared to the TOW ATGM (5 500 meters vs. 3 750 meters). This countermeasure resulted in significant losses among rebel ATGM crews in the past 2 years.

The total count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches for 2016 rose to 655.

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2017

After the loss of Aleppo in late 2016, many of the rebel‘s external nation-state supporters largely gave up on materially supporting Syrian rebels. At first, this resulted in lagging shipments, but a few months later the new U.S. administration decided to terminate the program Timber Sycamore – including shipments of TOW missiles to Syrian rebels.

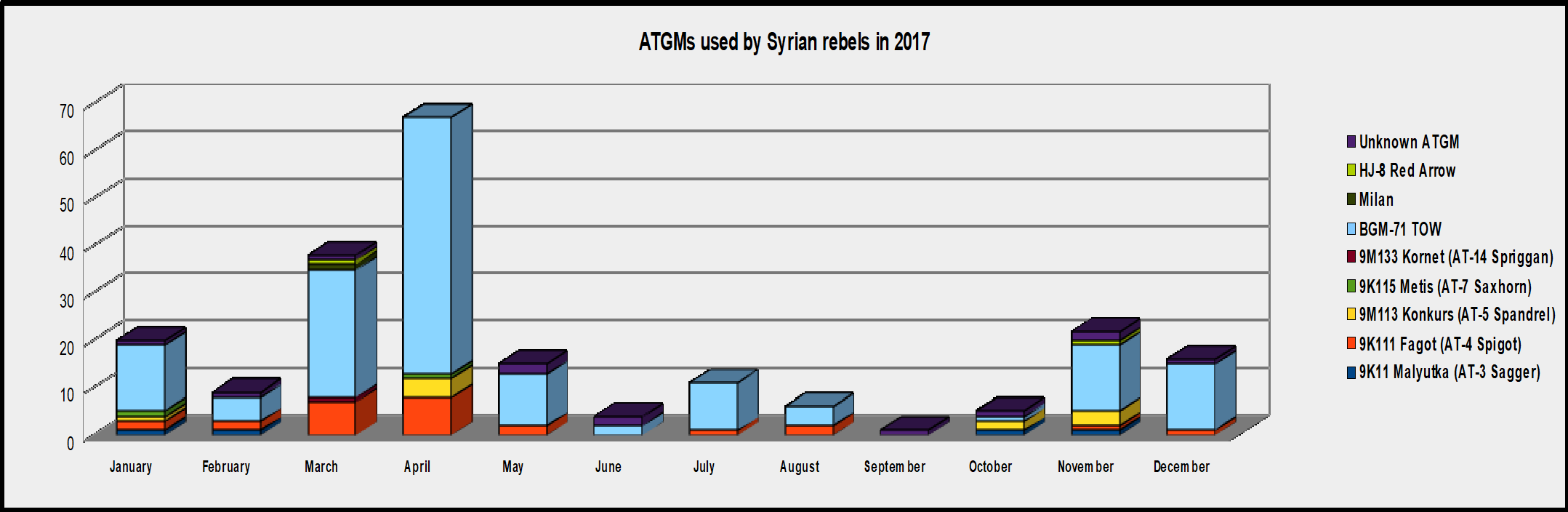

As a result, rebel use of ATGMs in 2017 declined significantly. This combined with increased rebel infighting made it far easier for the government forces to advance in areas like northern Hama governorate, where previously any advance came at a heavy material cost.

However, rebels were still capable of advancing into government-held territory, which rebels did in northern Hama in spring 2017 when rebels were able to advance again in northern Hama governorate. Rebels were at least temporarily able to hold their gains until government forces shifted some remaining half-decent units which in combination with RuAF airstrikes were able to recapture lost territory in the following weeks. During this rebel advance and later a pro-government counter-offensive, forces loyal to Assad again took significant losses from rebel ATGMs.

The total count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches for 2017 declined to 226.

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2018

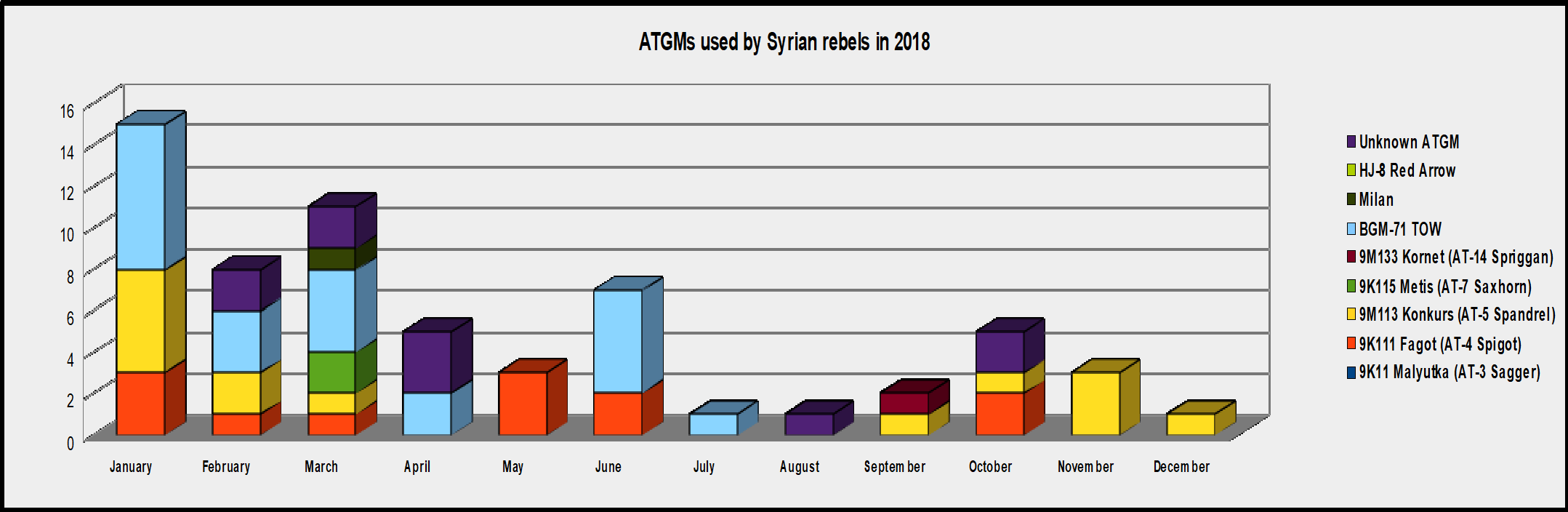

2018 started with an externally imposed calm on most fronts that began to warm up as the government forces gradually began eliminating rebel-held pockets as well as some areas in northern Hama and southern Idlib.

Due to the deployment of the Turkish Army between rebel and government positions opportunities for further offensives on the Idlib front are significantly limited for both sides. Rebels are now spending most of their effort on infighting, primarily between Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (al Nusra) and Ahrar al-Sham. This involves using the remaining stocks of ATGMs against each other.

In the past, rebels were able to capture ATGMs from pro-government positions, but because that is rarely possible anymore and the external supply of ATGMs was stopped, we can expect a further decline in the use of ATGMs by rebels as they gradually spend their stocks either due to infighting or in an effort to slow down pro-government offensives in various areas.

The number of ATGMs used by rebels in the second half of 2018 was minimal, due to the calm frontline and stop of infighting.

The total count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches for 2018 plummeted to just 64.

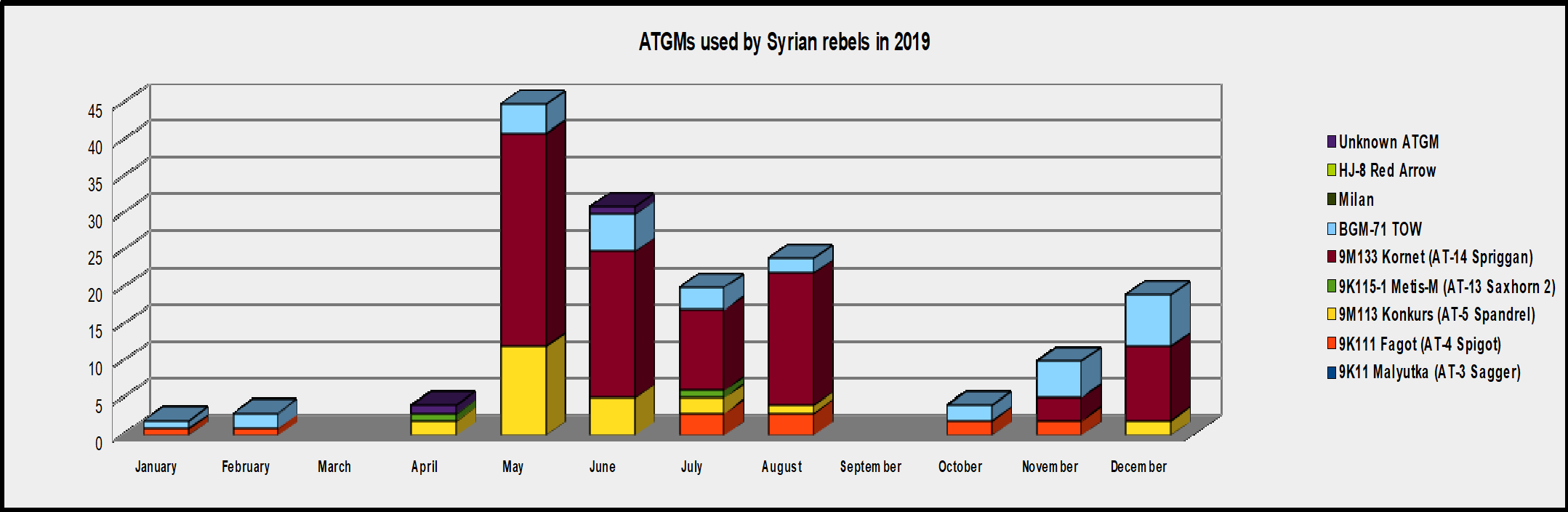

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2019

Early 2019 continued with externally imposed calm on the frontline (all rebel pockets have been eliminated by this time). That changed in late April when high-intensity fighting restarted. When that happened regime forces started a slow and costly advance in northern Hama. Since Turkey opposed regimes advance but didn’t want to be directly involved in fighting, they restarted shipments of ATGMs to rebels. While some of those ATGMs were familiar TOW-2A, a substantial % of new shipments were 9M133 Kornet (AT-14 Spriggan), which are slightly more powerful than TOW-2A and have better range (5 500 meters for Kornet versus 3 750 meters for TOW-2A). This didn’t stop the regime’s advance but imposed an increased cost for the regime’s advances and fighting mostly stopped again.

Meanwhile, the regime (mostly 4th Armored Division) also started a series of offensive to try to advance rebel-held in the northeastern part of Latakia governate, with the main objective being hills around Kabanah that dominate the area. Harsh terrain and dug-in defenders managed to prevent the regime from reaching its objective. While ATGMs weren’t as commonly used (compared to fighting in northern Hama) in this battle, they have helped to damage or destroy multiple regime armored bulldozers and tanks which the regime was using to clear path towards rebel fortified position. This has been the first regime offensive in several years that completely failed.

By December, the regime has shifted the bulk of its forces to the main frontline in northern Hama and southern Idlib and started relatively fast advancing there.

The total count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches for 2019 increased to 167.

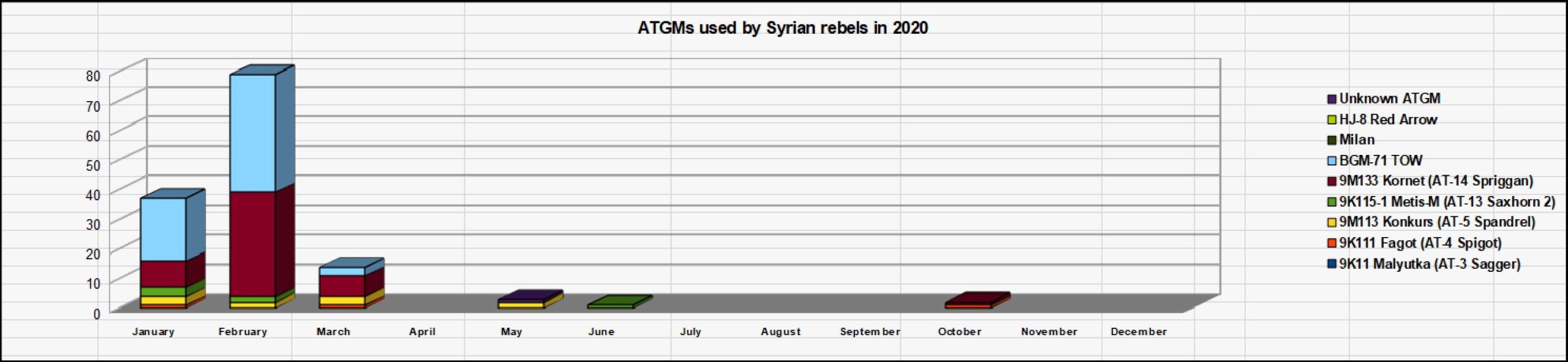

Syrian Rebel Use of ATGMs in 2020

2020 started with regimes hard push into southern and south-eastern Idlib and western Aleppo. By late February, the regime has managed to capture about a third of the rebel-held territory. During this time shipments of ATGMs from Turkey intensified as the regime forces advanced. While rebels have been quickly losing territory, especially in southern Idlib, they have used suppled ATGMs (and all other weapons they still had in reserves) to inflict heavy losses on advancing regime units. By late February (numbers from 2020.02.24) rebels have fired more ATGMs since the start of the month, than at any time since August 2016. The fighting mostly stopped in early March when Turkey and Russia agreed on a ceasefire and forced their allies to mostly accept it.

The total count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches for 2020 increased to 136.

The current count of visually confirmed rebel ATGM launches since the start of the Syrian Civil War is 2623.

Summary and Analysis of Rebel Use of ATGMs during the Syrian Civil War

While tracking rebel ATGM use during the Syrian Civil War has been more difficult than tracking pro-government armour losses which I covered in my previous article (tracking vehicle losses was made a lot easier by using after action footage), we can still derive significant information by analyzing the available data.

Any ATGM type, short of museum pieces like the 9K11 Malyutka (AT-3 Sagger), has a very good chance of hitting their target even if handled by non-nation-state actors. Based on the analysis of TOW strikes, rebels achieved a 76% hit rate, with 16.5% unclear result, 6.5% missed shots, and just 1% missile failures during the launch. It is likely that they achieved similar results with other SACLOS (Semi-automatic command to line of sight) ATGMs, while hits using obsolete MCLOS (Manual command to line of sight) ATGMs like 9K11 Malyutka (AT-3 Sagger) are likely in single-digit percents.

Armoured vehicles on any modern battlefield should expect to encounter powerful ATGMs and RPGs and if they do not have either modern ERA or a modern hard-kill active protection system, like Trophy APS, they are likely to take heavy losses if their opponent is either a nation-state or even just a competent militia with a nation-state sponsor.

Poor defensive preparations of Syrian Arab Air Force airbases on multiple occasions allowed rebels (and ISIS) to use ATGMs against operational planes and helicopters

HJ-8 operated by Liwa al-Tawhid used to target a government helicopter near Nairab Air Base in the Aleppo governorate, 16 November 2013.

Flexible opponents will gladly use ATGMs on targets against which they are not designed for, if they don’t have a desperate need to preserve those ATGMs for armored vehicles, since even with warheads designed against armored vehicles, ATGMs are a very effective way to eliminate targets like machine-gun nests, groups of infantry or artillery pieces which are near the frontline.

Pro-Assad forces rarely deploy smoke to hide from enemy fire either due to poor training and situation awareness or due to logistical issues. These forces are also quite poor at combined arms warfare, and as a result, their tanks are often exposed to enemy fire from a side where tank armour is much weaker compared to frontal armour.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=63ehKu7tYlY

When lacking a persistent aerial frontline reconnaissance and accurate artillery or quickly available combat aircraft, the most practical defense against enemy ATGMs is in many cases deploying your own ATGM teams and spotters.

The author would like to thank the following people for their invaluable help, with special thanks to @MENA_Conflict, @oryxspioenkop, @QalaatAlMudiq, @adambrayne7, @SCW_Nuggie, @DLAMNscw, @Mr_Ghostly, and the whole Bellingcat Investigation Team. Lastly, the author would like to thank the ‘SFM’ group (you know who you are) for sharing working links to footage that was likely to be quickly removed from public websites.