Hazardous Legacies: An Open-Source Overview of the Destruction of Deir ez-Zor’s Oil Industry

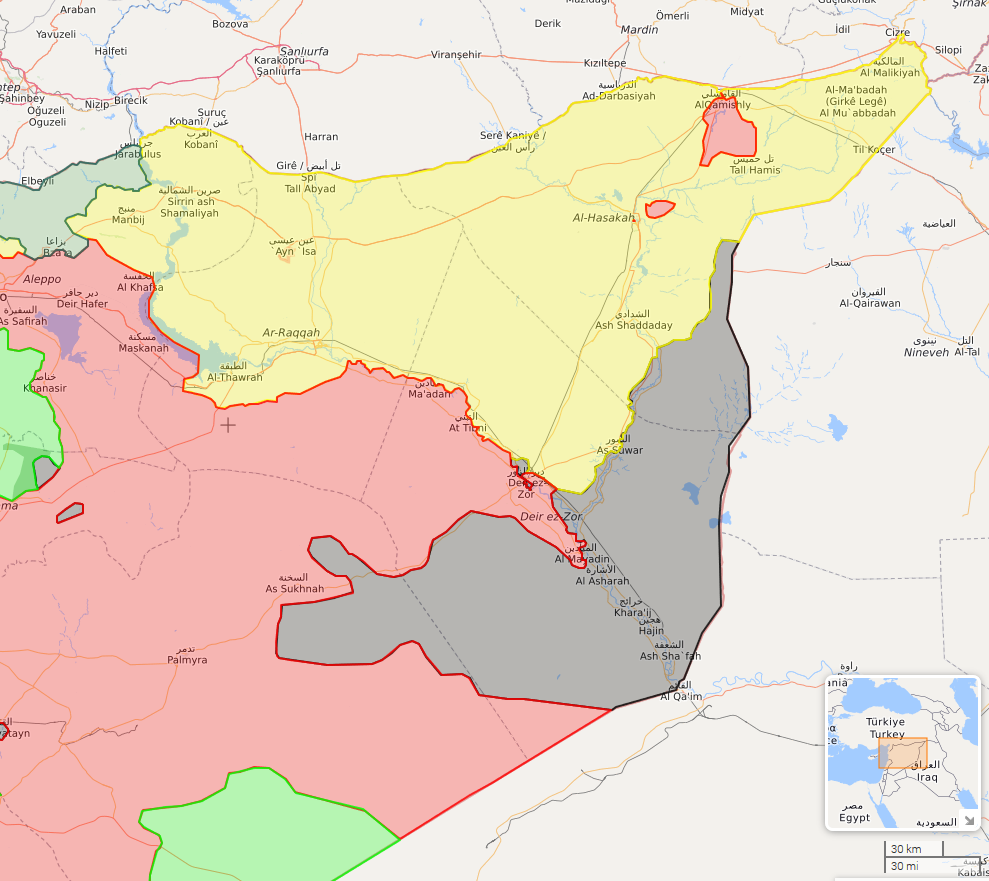

Now that the so-called Islamic State (IS) is rapidly losing terrain in eastern Syria, a race is underway to capture the oil-rich Deir ez-Zor governorate. The Syrian Arab Army (SAA) and militias loyal to the Syrian government, under cover of the Russian airstrikes, rush towards the fields east of the Euphrates River; but so does a contingent of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), backed by the United States-led Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR).

In the months and years before, air campaigns waged by both the Russian Air Force and CJTF-OIR have heavily targeted the same oil infrastructure their allies are now racing for. At the same time, scorched-earth tactics by the Islamic State accumulated the piles of pollution. These actions have left an environmental toxic footprint that is already posing health risks to local communities.

In this article, Wim Zwijnenburg and Christiaan Triebert explore the key development related to the key oil fields in Syria’s east by using open source information such as satellite imagery and local media reports. This analysed information suggests that there will be long-term consequences for social-economic reconstruction of the region, which has already become a power play between tribes, armed groups, and State actors. One question, however, remains: Who will deal with the environmental pollution and subsequent human health risks for affected communities in the aftermath of the conflict? Probably few, if any.

Deir ez-Zor: Syria’s Oil-Rich Governorate

Syria has never been a major oil player, but after Iraq it is still the largest producer among its neighbours such as Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, as Fanack notes. Before the war, in 2010, Syria’s produced around 2.5 million barrels per year according to the Survey of Energy Resources issued by the World Energy Council. The Deir ez-Zor province contains roughly 40% of the country’s oil reserves, and there are several natural gas fields. Despite the rich oil revenues, Deir ez-Zor saw little of the oil wealth returning to the city and its surroundings.

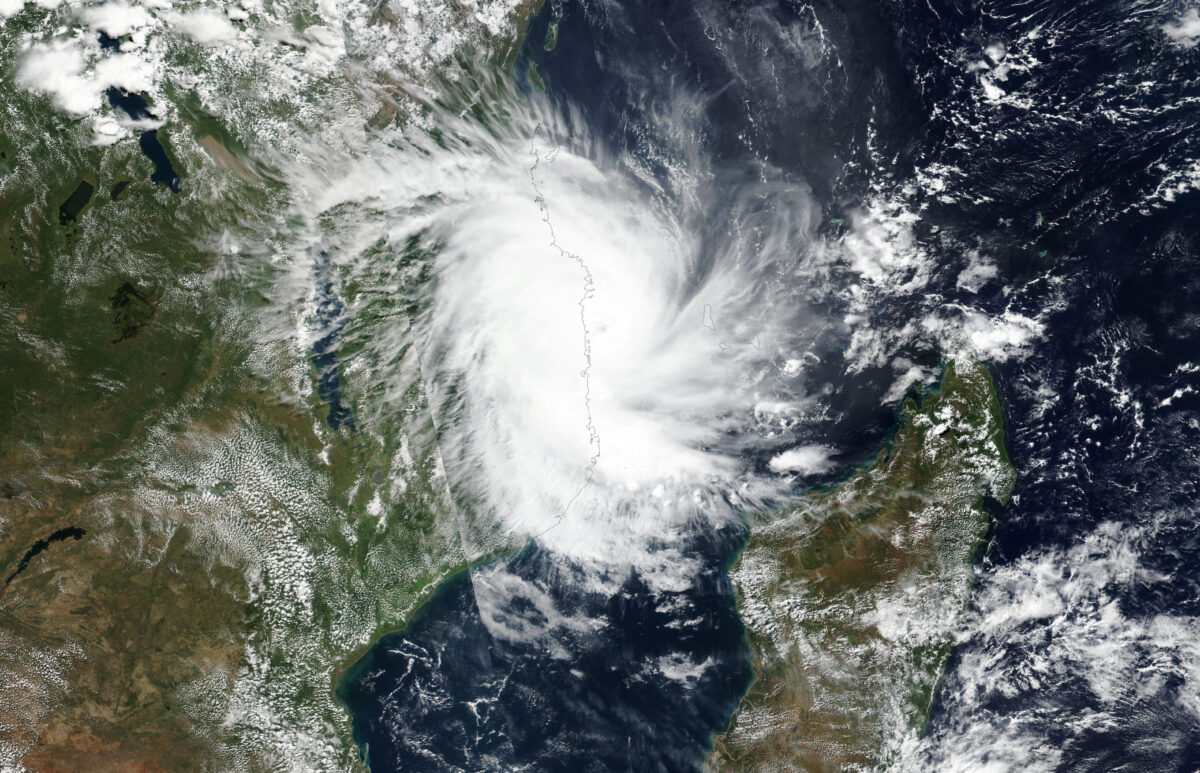

Image 1. Territorial control as of October 17, 2017, based on open source information, in the Deir ez-Zor province (highlighted) in Syria’s east, with SAA and allies in red, SDF and allies in yellow, and IS in black. Credit: Liveuamap.

Alternative Oil Economies in Time of War: The Rise of Backyard Refining

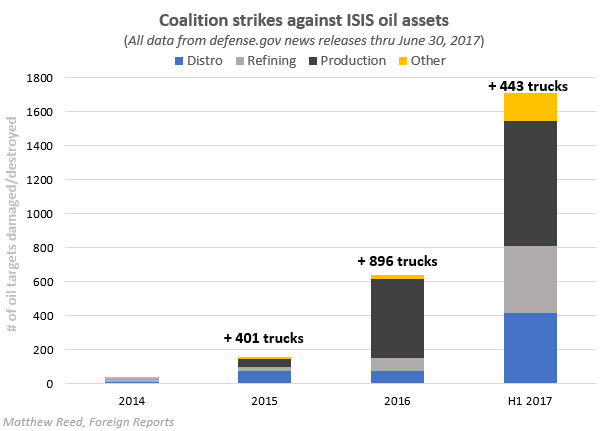

In late 2011, as the peaceful popular uprisings in Syria slowly turned into an armed conflict with the Syrian government led by President Bashar al-Assad, many civilians started to flee the clashes, especially after groups took up arms against the SAA and its allies. Among those fleeing were many engineers and professionals from the country’s oil industry, while others joined armed groups. As a result, the output of Syria’s oil industry slowed down significantly. Fighting also erupted around oil facilities, with in 2014 the CJTF-OIR and in 2015 the Russian Air Force starting to target IS-controlled oil infrastructure with airstrikes, including refineries, as the militant group used oil trade and smuggling as a way of income generation. CJTF-OIR’s ‘Operation Tidal Wave II’, to ‘cripple’ IS oil trade, started in October 2015 – a ‘major success’, as Matthew M. Reed, vice president of oil-consultancy firm Foreign Reports asserted in Foreign Policy.

Source: The Fuse, Matt Reed, Foreign Reports. July 12, 2017

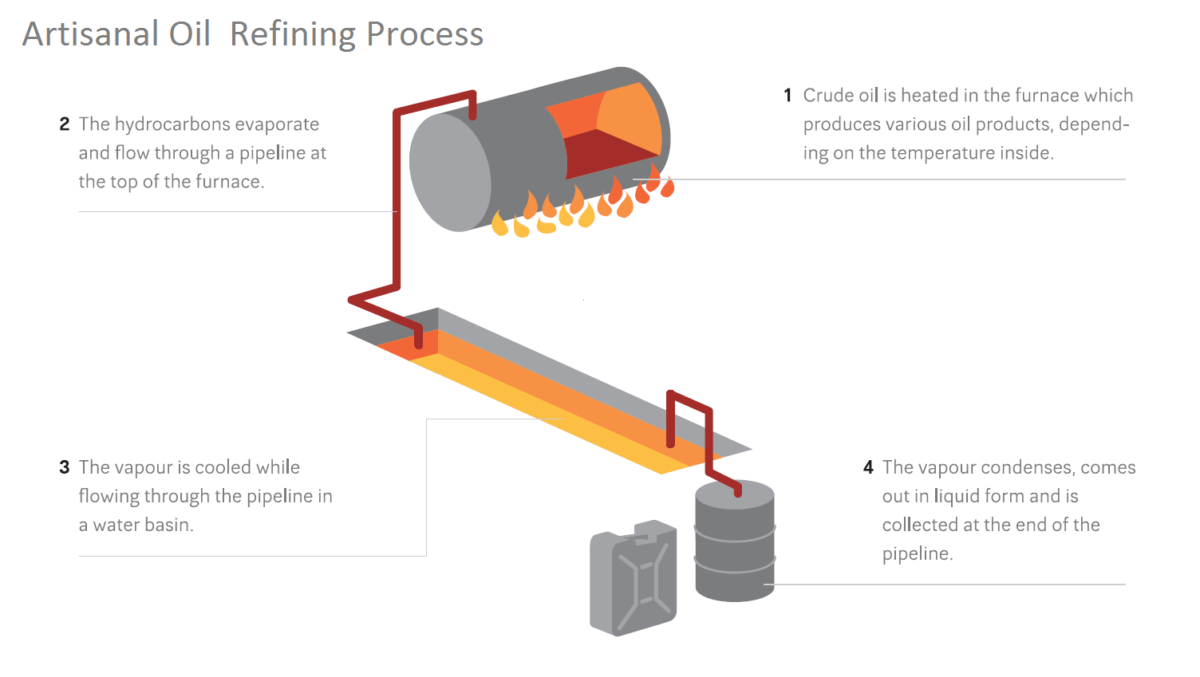

Both the internal displacement of Syrians and the attacks on oil infrastructure contributed to the rise of artisanal oil refineries. At these makeshift structures crude oil is refined into a useable product for sales on the local market or smuggled to buyers in government controlled areas and Turkey.

Image: Google Maps, September 16, 2014

Earlier satellite analyses by PAX have demonstrated that this way of refining oil has become a major alternative economy in Syria, with tens-of-thousands refineries all over the country. These artisanal refineries are mostly run by civilians, not rarely children that work in hazardous circumstances and are exposed to toxic materials. Apart from the serious health issues, artisanal oil refineries are leaving a significant local environmental footprint as it generates toxic waste products which create localised pollution, and can result in contamination of local surface and groundwater sources, potentially resulting in long-term environmental health risk to communities.

Image. Men and young boy working at a makeshift oil refinery site in Syria pose for a portrait photo. Photo: Yann Renoult, 2014.

Environmental health risks of targeting oil sites

Predicting the environmental fate and effects of oil products released into the environment is complicated by the fact that oil products are composite of a number of chemicals. The oil in spills will partially degrade, a fraction will volatilise while the remainder adhering to soil and sediments. In general, short-chained aromatic compounds such as benzene, toluene, ethylene and xylene (“BTEX”) are highly mobile and volatilise easily. Longer-chained compounds such as large alkanes have a very low solubility, often remaining attached to local soil and sediments. In general, the short-chained and aromatic compounds pose a greater threat to humans and the environment as they move into soil and air, exposing people via inhalation. The threat depends on the quantity released, the composition of the oil and the age of the released oil products. Groundwater pollution may occur where oil products leak from damaged storage tanks or facilities onto the soil surface. Ground and surface water pollution threatens agricultural land and the people who use ground and surface water for irrigation, drinking and domestic purposes.

Long-term exposure to some of the oil-related substances (BTEX and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons – PAHs) may lead to various health problems [PDF], such as respiratory disorders, liver problems, kidney disorders, and cancer, depending on the duration and intensity of exposure. Oil pollution can be especially problematic for local ecological receptors, as certain animals such as birds are very sensitive to exposure to petroleum compounds. Oil fires release harmful substances into the air, such as sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and lead. The nitrogen and sulphur compounds are associated with acid rain, which can have a negative impact on vegetation and lead to the acidification of soils. Furthermore, these substances can cause severe short-term health effects, especially to people with pre-existing respiratory problems. The larges cale release of PAHs can have a potentially severe long-term environmental impact. PAHs are very persistent organic compounds, some of which are potential carcinogens and can cause respiratory problems. When released by fires, they can be transported over a large area before deposition in soils.

Regionally, various countries have struggled with the impact of oil pollution. From the Iran-Iraq war, where various oil installations in souther Iraq and Iran were targeted, to the Kuwait oil fires in 1991 and subsequent widespread ecological damage done by the hundreds of burning oill wells to the oil spill in Lebanon in 2006 when Israel targeted an oil storage tank at the Jiyeh power plant that impacted the local environment. Israel witnessed a environmental disaster in 2014 when millions of liters of crude oil, or 31.000 barrels, leaked into the environment near Eilat. The clean-up up and remediation operations is estimated to cost over $100 million dollar. In 2016, IS set fire to over 20 oil wells at Qayyarah, resulting in the burning of 2 million barrels of oil, and the leaking of ‘tons of thousands of barrels’, according to a statement by the Iraqi governor to the UN in Nairobi, September 2016. A UN Environment Technical Note on Iraq [PDF] published in September 2016 provides more details on the oil damage done the Qayyarah oil field.

A View from Space on Syria’s Oil-Related Environmental Damage

Three years of airstrikes against a variety of oil industry targets, combined with scorched-earth tactics used by IS while retreating (e.g. by setting fire to oil wells or blowing up gas fields) has left a significant mark on Syria’s landscape.

Among the targets were dozens of oil storage sites and refineries, close to a thousand oil wells and almost 2,000 oil trucks, severely damaging Syria’s overall oil infrastructure. Since the onset of the strikes, visual confirmation as seen in strike videos released have showed the many burning oil storage sites, attacks on artisanal refineries, tanker trucks and well heads.

Twitter-user @obretix has mapped (and geolocated) a large share of the airstrike videos by the U.S.-led Coalition and the Russian Air Force, displayed below on two separate maps.

Unfortunately, most of the videos with imagery from the air strikes linked in the maps have been removed from YouTube. Below are some examples of videos still available on the Defense Video Imagery Distribution Systems (DVIDS).

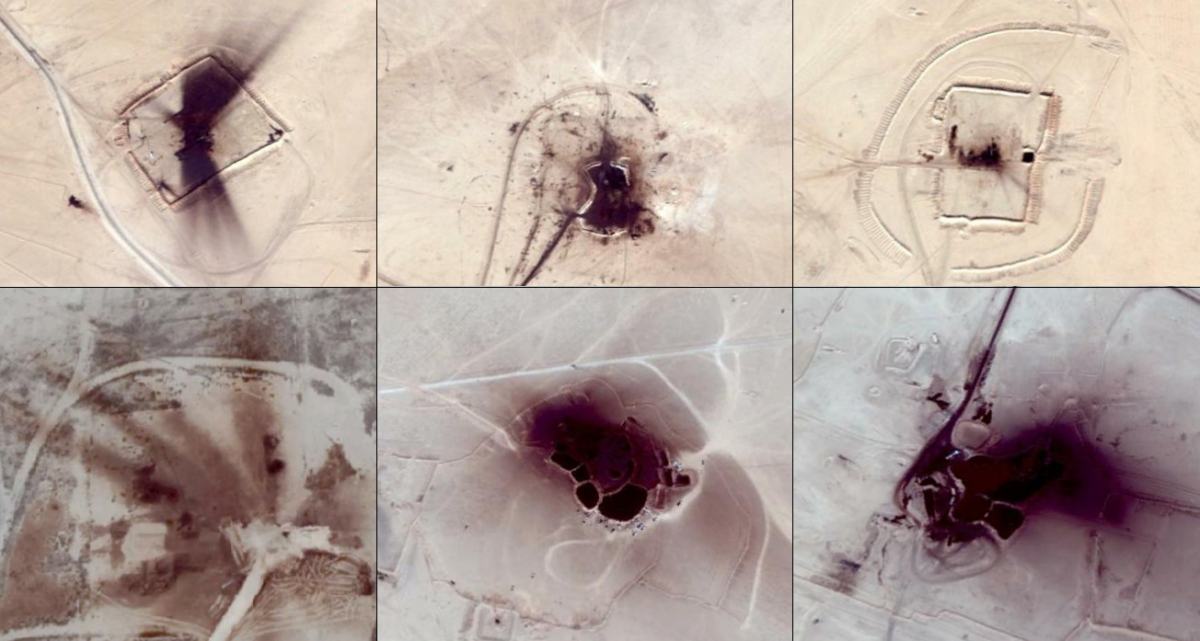

Other refineries and oil facilities on various oil fields in Deir ez Zor have been heavily damaged and major oil spills can be seen on recent satellite imagery:

Azraq Oil Facility

Oil facility at #Azraq oil field in #DeirEzzor also heavily damaged, with major spillsat nearby #oil wells seen @ https://t.co/634lvtskhe pic.twitter.com/4w0HMGGclW

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) October 11, 2017

Maleh Oil Field and Fefinery

Maleh #oil field and refinery in east #DeirEzzor heavily damaged with major on-site oil spills https://t.co/6miuCq8clN pic.twitter.com/LlkwB9UzUJ

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) October 11, 2017

Wadi Ubayd Oil Refinery

Wadi Ubayd #oil refinery in #DeirazZor also severely damaged due to airstrikes, with quite some oil spills on-site https://t.co/6YzLV5nHKZ pic.twitter.com/j60r9SLt8k

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) October 11, 2017

El Ward Oil Refinery

El Ward #Oil refinery in #DeirEzzor severly damaged by (likely) airstrikes in the last couple om months https://t.co/1pr6FxloT5 pic.twitter.com/uvgKkdusOo

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) October 11, 2017

Omar and Tanakh Oil Refineries

E. #Syria: infrastructures of Omar Oil Fields (SE. of #DeirEzzor) largely wrecked. https://t.co/RKS8E8473u pic.twitter.com/JVuDyt9lZY

— Qalaat Al Mudiq (@QalaatAlMudiq) August 4, 2017

Impact craters of airstrikes at pumping jacks, black oil track from fuel trucks, and oil spills from damaged wells are also clearly visible.

Image: Overview of damaged oil wells and various storage pits in Deir az Zor. Source: Google Earth 2014, 2016

The attacks on the well heads and limited opportunities for storage and transportation resulted in rudimentary solutions to store the crude oil, such as large oil pits near the major wells and refineries.

PT: Imagery from Feb '17 shows pools of crude #oil next to the well at El Isba field #deirazZor Might be these are set on fire now pic.twitter.com/bnQ1DSj9IM

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) September 22, 2017

Another pollution problem resulted from (likely) amateurish techniques to pump up oil, which have also led to oil wells leaking. These rivers of crude oil can be observed at various locations in northern Syria, and were discussed by one of the authors on Planet Labs in September 2017.

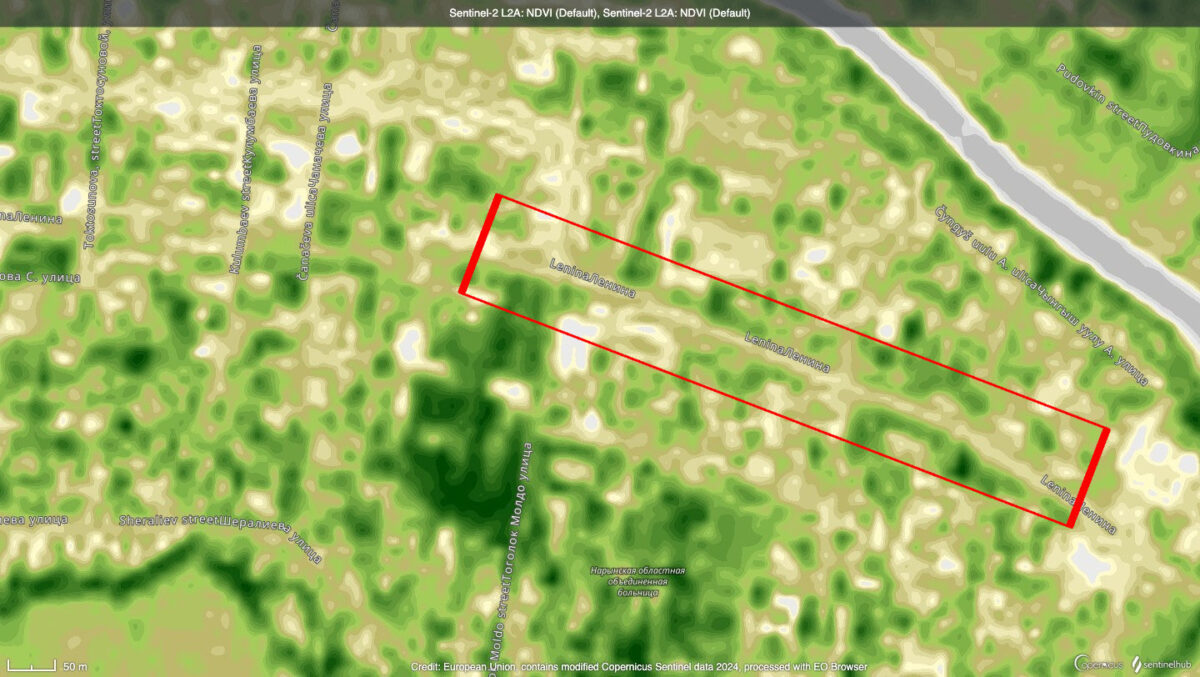

Image. Oil spill from El Isba wells. August 2017 Credit: Sentinel 2/Digital Globe

Image. Spills from various well at Kabibah oil field, Hasakah governorate. September 16, 2014 Credit: Google Earth.

Considering the potential localised and even wider environmental footprint of the airstrikes, scorched earth policies and alternative fuel economies, Syria will need to deal with a toxic legacy from the damage done to its oil industry. Yet a proper assessment cannot be made yet, as larger issues loom on the horizon. Despite these damages, there remain vast amount of oil and gas reserves in the many oil fields that are now becoming the trophy for all parties involved in the conflict, and may have wide geopolitical ramifications for the shape of Syria to come.

Overview Of All Damaged Oil Facilities, Oil Spills and Artisanal Oil Refineries in Syria

All the information in the article has been collected and stored in this Google Maps overview.

The Scramble for Deir ez-Zor’s Oil: Who Will Control the Fields after IS?

On September 5, 2017, the Syrian military finally broke the siege by the so-called Islamic State (IS) on Deir ez-Zor. It marked the end of a three year blockade on the city by the militants that started in 2014 and resulted in an ongoing humanitarian crisis. A few days later, on September 9, CJTF-OIR welcomed the start of “Operation Jazeera Storm” by the Syrian Arab Coalition (SAC) to defeat IS in the Khabur River Valley north of Deir ez-Zor city. SAC is claimed by the U.S. as an alliance within the SDF of exclusively ethnic Arab militias. The Kurdish People’s Defence Units (YPG) also announced the operation on an affiliated website. Once cleared from IS militants, the valley “will be turned over to representative bodies of local civilians who will then oversee security and governance as with Tabqa and Manbij,” CJTF-OIR said.

While CJTF-OIR’s spokesman said he was aware of strategic value of the territory, he claimed the coalition “is not in the land-grabbing business.” However, both the SDF’s commander-in-chief and the leader of SDF’s Deir ez-Zor military council have expressed differently. Quoted by NPR, Ahmed Abu Khawla, the leader of SDF’s Deir ez-Zor military council said they “want to defeat [IS], and then liberate not only the oil fields but all the land factories and people”. Abu Khawla is originally from a powerful tribe in the area.

The forces aligned with the Assad government are coming from the north(west) and west, while the SAC is pushing southward from the north. Syria Deeply has tracked the advances of both in late September 2017. The U.S. has already accused Russia of bombing SDF fighters, a claim Russia denied and blamed the U.S. for the death of its general instead.

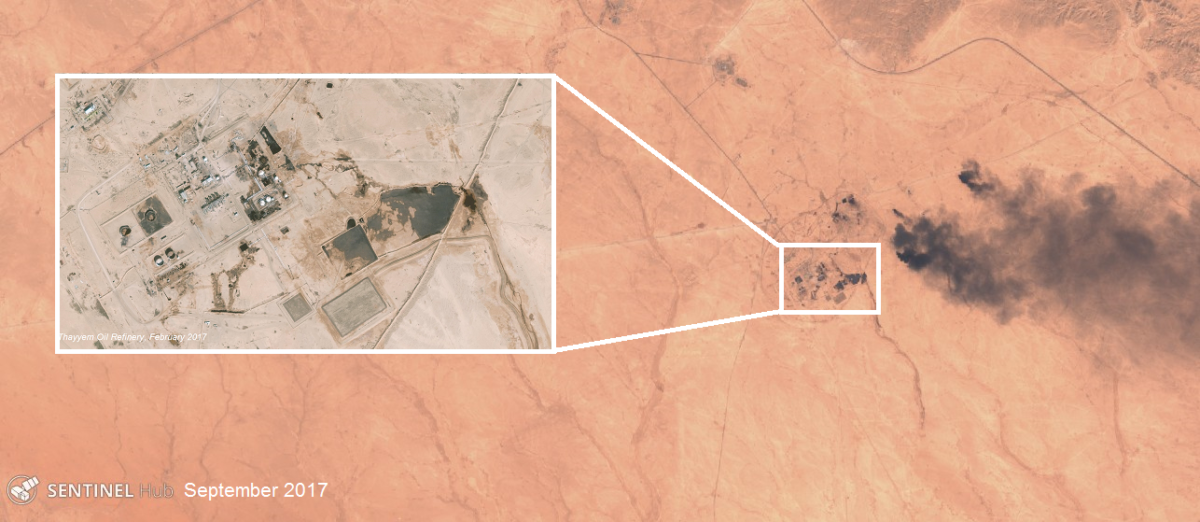

As the U.S.-backed SDF current races towards the eastern oil field in Deir ez-Zor, the Syrian army, supported in the air and on the ground by Russia, as with Iraqi and Iranian militias on their side, also have set sights on the same oil wealth. In the last year, the latter group managed to retake gas and oil fields near Palmyra, and recently managed to reclaim the Al-Tayyem oil field south of Deir ez-Zor city, but not before IS managed to sabotage some of the oil pipelines, resulting in a localised oil spill among the many other nears the refinery.

Image. Crude oil leakage from pipeline at Tayyem oil refinery, September 2017. Credit: Screengrab from Al Masdar News.

Image. Burning wells north east of Tayyem refinery and oil spill south of the location. Credit: Sentinel Hub, September 10, 2017

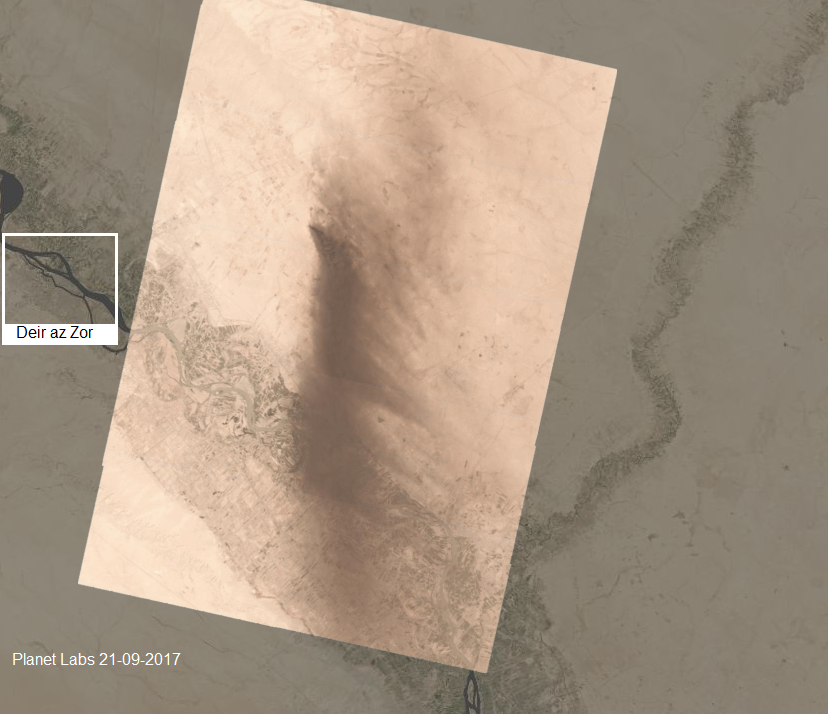

From the north, the SDF in a quick move secured the Conoco gas facility and nearby El-Idra oil field. A local oil pit was set on fire by IS during their retreat, likely to create a cover smoke screen. Though a huge fire was visible on Planet Labs imagery, the fire was out in two days.

Image. Burning oil pit at El Isba field. Credit: Planet Labs.

Image: Zoom-out of burning oil pit at same location. Credit: Planet Labs

Soon after, the SDF managed to take over the Jafra oil refinery. In the course of the fighting, some fires broke out south and west of the refinery, as can be seen in the Planet Labs and Sentinel images below from September 28th and October 17th 2017

Image: Fire south of Jafra Oil Refinery. Credit: Planet Labs, September 28, 2017

Image: Oil pit burning at Jafra, October 17, 2017. Credit: Planet Labs

Another small oil well was set ablaze west of the refinery, which is still burning at the date of the publication.

Image. Jafra oil refinery with burning oil pits/wells, October 5, 2017, Credit: Sentinel 2.

Constraining IS’s Appetite for Destruction

Considering the destructive nature of IS’s retreating tactics, as they set ablaze dozens of oil wells in Iraq in 2016 and 2017, it can be expected that they will resort to similar scorched-earth policies in Syria. However, there is reason to believe that there may be other factors at play in Deir ez-Zor, that could see a different approach.

In 2012, Deir ez-Zor’s local tribes took over the oil fields with their armed groups after pushing out the SAA, and started to make money from smuggling and crude refining. When Jabhat al-Nusra, at the time’s Syria’s Al-Qaida affiliate, and Free Syrian Army (FSA) groups took over the area in 2013, deals were made with local tribes over the control of the oil fields, various research reports indicated, for example the Carnegie Foundation and a publication by the German non-governmental organisation Fraternity Foundation for Human Rights. Yet this seemed not to go without a struggle, as some clans aimed to keep control over the oil wells.

Subsequently, Nusra allegedly used political tactics to gain control over the Omar oilfield under the guise of unifying all armed groups in a Sharia board, which then would control all the oil. But this did not land well. Perhaps as a result, some groups started to support newcomer IS in 2014, who then exploited these disputes to finally take control over all the wells and demanding alliance to its leader. The power of the local clans and IS dependency on their support might explain the limited actions by IS against the oil fields, as they provide the income for the local clans. Setting the wells ablaze would therefore have serious implications for the livelihood of the clans, and it is not likely they would allow IS to do so.

Pollution problems: What is Next for Deir ez-Zor’s Citizens

What will be next for Deir ez-Zor’s future in the aftermath of the conflict? The ongoing fighting has left a large part of the oil industry in rubble, and has brought with it a long road to recovery, as highlighted by the World Bank in The Toll of War report, published in July 2017. . An important question will not only be related to the economic consequences, but rather political issue over who will control which oil field. These questions however fall outside the expertise of the authors.

Instead, this article aims to address the relevancy related to the political accountability for the damage done related questions about who is going to fund clean-up, remediation and provide support to affected communities. These actions, and related risk education and awareness raising programs are highly needed to minimise exposure to pollution caused by environmental damage. Therefore, this article has especially focused on the potential polluting impact on livelihoods and has raised concerns over environmental health risks for those living near polluted sites or working in the alternative artisanal oil industry.

Clearly, the rise of artisanal oil refining has brought alarming health problems for the individuals, in particular children, working at these sites. Working daily in hazardous conditions, inhaling noxious fumes and being exposed to toxic waste will have acute and long-term health risks. The press agency TransTerra Media provides a disturbing insight in the conditions of the workers at this sites in this video at Qamlishi, northern Syria in 2014, describing all the illnesses and diseases they are facing on a daily basis. These practices will likely continue even after the guns fall silent, as for many households, it is one of the few ways to provide an income.

The targeting of oil facilities by all warring parties also left visible scars on Deir ez-Zor’s environment. Burning oil wells and storage pits, spills from pipelines, direct pollution from exploded refineries and toxic waste from artisanal refining has likely resulted in dozens of environmental hotspots.

Image: Internally Displaced Person’s Camp in Hasakah set up between artisanal oil refineries, exposing civilians to toxic waste . Source: ICRC, Sentinel 2, August 2017

Assessing the impacts and addressing State responsibility for conflict-related pollution have been addressed last year at the second meeting of the United Nations Environmental Assembly (UNEA). A resolution, titled the “Protection of the Environment in Areas Affected by Armed Conflict”, was submitted by Ukraine and co-sponsored by Jordan, Iraq, Norway and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and was approved by consensus. The UN resolution outlined concerns over environmental damage caused by armed conflicts and, among other things, called for

“Member States to continue to support, where appropriate, the development and implementation of programmes, projects and development policies aimed at preventing or reducing the impacts of armed conflicts on the natural environment”.

This year, the Iraqi government will submit another resolution at UNEA-3, taking place in December in Nairobi. The resolution will address pollution caused by armed conflicts and terrorist operations, and is born from Iraq’s issues around the major impact of the burning oil wells at Qayyarah and the fire at the Mishraq Sulphur factory, set ablaze by IS. Both resolutions are useful stepping stones to address the environmental impacts of conflicts and dealing with cleanup of toxic remnants of war. In the case of Syria, it is likely that few, if any, will take responsibility for the environmental damage caused by the conflict. Sadly, it will be the civilian population who will have to deal with the environmental legacies and resulting health risks brought upon them.

The authors would like to thank Twitter user @obretix for the data on makeshift refineries and strikes, Foeke Postma for additional mapping