A History of Sarin Use in the Syrian Conflict

Through the course of the Syrian conflict, there have been multiple allegations related to the use of Sarin as a chemical weapon. While the April 4, 2017 Khan Sheikhoun and August 21, 2013 Damascus attacks are what most people are familiar with, Sarin has been used as a chemical weapon in Syria on multiple occasions, often virtually unnoticed.

This lack of attention on some Sarin attacks has created a false perception that the Khan Sheikhoun and Damascus Sarin attacks were the only time Sarin has been used in Syria. This misperception is often combined with the belief that chemical weapon attacks as a whole are rare events in Syria, when in fact dozens, if not hundreds, of attacks have occurred over the last 5 years of the conflict. The vast majority of these attacks involve allegations of the use of chlorine as a chemical weapon, with the OPCW-UN Joint Investigation Mechanism (JIM) confirming the use of chlorine as a chemical weapons by Syrian government forces (in addition to confirming use of chemical weapons by ISIS), but what is often under-covered is the number of Sarin attacks, the progression of the use of Sarin in attack, and their relationship with one another.

While there’s no exhaustive list of chemical attacks in Syria, a number of individuals and organisations have attempted to produce as complete a list as possible. When compiling a list of this type, there are a number of challenges, in particular the reliability of sources. Although there have been dozens of chemical attacks alleged in Syria, only a handful have been investigated by international bodies. Therefore, for the most part, reports are based on claims and documentation by local activists, defectors, and investigations by journalists. While this article attempts to review the use of Sarin in the Syrian conflict, it is possible that there are more incidents of Sarin use, but the attack was too poorly documented to identify the use of Sarin.

The First Signs of Sarin?

Data from various sources, including declassified material from French intelligence, a timeline from the Arms Control Association, and The Havard Sussex Program on Chemical and Biological Weapons, points to 2012 as the year with the first allegations of chemical weapon use in Syria, and one of the first allegations of use of Sarin being a December 23, 2012 incident in the Khaldiyeh and Bayada neighborhoods of Homs. Several videos posted online showed the victims of the attack (playlist), with one video published with English subtitles:

Local activists quoted by Al Jazeera on December 24th stated “We don’t know what this gas is, but medics are saying it’s something similar to sarin gas.” Al Jazeera later cited a “former scientist for the Syrian chemical weapons programme” who claimed Sarin was used to halt advances by rebel forces in a number of towns, including “Homs’ al-Khalidiyeh district,” and that a “diluted mix of sarin and isopropyl alcohol was likely used in December 2012.”

However, the claims of Sarin use were also made alongside claims that another chemical agent was used in the attack, known as “Agent-15” or “BZ“. The Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) interviewed witnesses and victims of the attack, and described the “probable” use of BZ:

“The Gas effects started [a] few seconds after the area was shelled. Right after the shelling, patients described seeing white gas with odor, then they had severe shortness of breath, loss of vision, inability to speak, flushed face, dizziness, paralysis, nausea and vomiting, and increased respiratory secretions. Doctors who treated patients said that patients had pinpoint pupils and bronchospasm. Patients were treated in a field hospital. Gas masks were not available.”

In January 2013, Foreign Policy published details of a cable, signed by the U.S. Consul General in Istanbul, Scott Frederic Kilner, and sent to the State Department, detailing the consulate’s investigation into reports of chemical weapon used in Syria. This included interviews with activists, doctors, and defectors, including Mustafa al-Sheikh, a high-level defector and key official in Syria’s WMD program. Foreign Policy reported that an Obama administration official stated that “We can’t definitely say 100 percent, but Syrian contacts made a compelling case that Agent 15 was used in Homs on Dec. 23.”

The day after the Foreign Policy report was published, White House National Security Council spokesman Tommy Vietor said in a statement: “The reporting we have seen from media sources regarding alleged chemical weapons incidents in Syria has not been consistent with what we believe to be true about the Syrian chemical weapons program.”

While the exact nature of the chemical agent remains unclear, the results of its use were between 5-7 reported deaths, and 50-100 injured, according to doctors contacted by Foreign Policy, and reports by SAMS published by the US-based Humanitarian Resource Institute.

Khan Al Assal

On the morning of March 19, 2013, reports were published by the Syrian news agency SANA accusing rebel groups of attacking the town of Khan Al Assal, west of Aleppo city, with chemical weapons. Initial reports from state media claimed the attack launched from rebel-held Kafr Dael, 5 kilometres north of Khan al Assal, killed “25 people and wounded dozens,” with a Reuters photographer describing what he encountered at hospitals treating the victims:

A Reuters photographer said victims he had visited in Aleppo hospitals were suffering breathing problems and that people had said they could smell chlorine after the attack.

“I saw mostly women and children,” said the photographer, who cannot be named for his own safety.

He quoted victims at the University of Aleppo hospital and the al-Rajaa hospital as saying people were dying in the streets and in their houses.

In addition to the civilian victims, various sources claimed soldiers had been victims of the attack, with the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights claiming in initial reports that 16 soldiers were among the dead. Footage of the victims receiving treatment was published by SANA and broadcast by international media:

The response of the Syrian opposition was to allege forces loyal to the Syrian government were responsible for the attack:

“The Aleppo Media Center, affiliated with the rebels, said there were cases of “suffocation and poison” among civilians in Khan al-Assal after a surface-to-surface missile was fired at the area. It said in a statement the cases were “most likely” caused by regime forces’ use of “poisonous gases.”

An activist in Aleppo province who identified himself as Yassin Abu Raed, not his real name, confirmed the attack and said there were at least 40 cases of suffocation in the area and several deaths. But he said no details were available as casualties were being taken to a government controlled area in Aleppo.

Abu Raed declined to give his real name because of security concerns.

He said it did not make sense for the rebels to fire a chemical weapon at an area they had recently seized, and accused the government instead.

“Why would the Free Syrian Army bomb themselves with a chemical weapon?” he asked.”

Russia supported the Syrian government allegations, while the United States denied rebel groups had used chemical weapons. On March 20th, the Syrian government contacted the UN Secretary General, requesting “a specialized, impartial and independent mission” to investigate Khan al-Assal, with other member states requesting an investigation of all chemical incidents reported in Syria. By March 26th, the Secretary General had appointed Professor Åke Sellström to head the United Nations fact-finding mission to investigate the use of chemical weapons in Syria.

Meanwhile, both sides continued to accuse each other of being responsible for the attack. The Daily Telegraph cited a senior source close to the Syrian Army, who claimed “that a home-made locally-manufactured rocket was fired, containing a form of chlorine known as CL17,” and that a “home-made rocket was fired at a military checkpoint situated at the entrance to the town.” It went on to claim:

“The military source who spoke to Channel 4 News confirmed that artillery reports from the Syrian Army suggest a small rocket was fired from the vicinity of Al-Bab, a district close to Aleppo that is controlled by Jabhat al-Nusra – a jihadist group said to be linked with al-Qaeda and deemed a “terrorist organisation” by the US.”

This contradicted earlier claims made by Syrian government officials that the attack had been launched from Kafr Dael, 5 kilometers north of Khan al Assal. The report also referred to the presence of a chlorine factory in Aleppo, which Time reported had been captured by Jabhat al-Nusra. The smell of chlorine reported by victims of the attack was highlighted in the Time report:

“Survivors and witnesses of what was being described by the government news agency as a chemical attack said they smelled something like chlorine. And as the owner of Syria’s only chlorine-gas manufacturing plant, Sabbagh knew that if chlorine was involved, it most likely came from his factory.”

Syrian Prime Minister Wael Nader al-Halqi provided a different version of events, claiming that Sarin was “manufactured in Turkey and funneled to the terrorists.” Other sources claimed 80mm mortars filled with chemical agents were used, not home-made rockets, and were fired from Kafr Dael, not al-Bab or a “military checkpoint situated at the entrance to the town.”

To add to the confusion, the Russian government shared a lengthy report with the UN in July detailing their investigation into the attack. While this report has never been made public, the Russian government did make some of the conclusions of the report public.

They claimed the “Basha’ir al-Nasr” brigade affiliated with the Free Syrian Army launched a “Basha’ir-3” unguided projectile at Khan al-Assal, which they claimed was filled with Sarin. This information, and samples gathered by the Russians, were provided to the UN investigation into chemical attacks into Syria.

In December 2013, the report by the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic, set up in the wake of the Khan al-Assal attack, detailed the mission’s conclusions on the attack. Despite alternative scenarios presented by various parties in the period between the launch and the attack, the mission report confirmed the original Syrian government allegation:

“…armed terrorist groups had fired a rocket from the Kfar De’il area towards Khan Al Asal in the Aleppo governorate. According to the letter, the rocket had travelled approximately 5 kilometers and fell 300 meters away from a Syrian Arab Republic army position. Following its impact, a thick cloud of smoke had left unconscious anyone who had inhaled it.”

There was no mention of 80mm mortars or an attack from al-Bab or a military checkpoint on the entrance of the town, and the conclusion of the mission report was:

“The United Nations Mission collected credible information that corroborates the allegations that chemical weapons were used in Khan Al Asal on 19 March 2013 against soldiers and civilians. However, the release of chemical weapons at the alleged site could not be independently verified in the absence of primary information on delivery systems and of environmental and biomedical samples collected and analysed under the chain of custody.”

The chemical agent believed to have been used, according to the mission report, was “an organophosphorous compound,” with “no other suggestions as to the cause of the intoxication.” This would exclude the use of chlorine as the chemical agent used in the attack, despite earlier claims to the contrary.

The appendices of the report contained more details of the investigation, including images illustrating the locations in question:

The Khan Al Asal area west of Aleppo is indicated in red. This figure also illustrates the location of the Kfar De’il area, as well as some hospitals and some military installations (as per the UN report)

The impact point (upper yellow pin) can be noted south of the Aleppo-Idlib road. The location of an interviewed witness is illustrated as the lower yellow pin north of the M 45 road. As indicated by the two red pins, most victims were, according to the witness, located south of the Aleppo-Idlib road and west from the release point (as per the UN report)

This section provides more details of the attack provided by witnesses, such as witnesses described “a yellowish-green mist in the air and a pungent and strong sulfur-like smell” after the impact of the munition. With regards to the munition, the UN mission report did not clarify the type of munition used:

“The United Nations Mission received contradicting information as to how chemical weapon agents were delivered in the Khan Al Asal incident. Witness statements collected by the UNHRC Commission of Inquiry, provided to the United Nations Mission, supported the position by the Syrian Arab Republic that a rocket was fired from the neighborhood. However, according to other witness statements to the UNHRC Commission of Inquiry, an overflying aircraft had dropped an aerial bomb filled with Sarin.

The United Nations Mission was not able to collect any primary information or any “untouched” artifacts relevant to the incident and necessary for an independent verification of the information gathered.”

The uncertainty about the type of munition was inconsistent with the claims made by the Russian government, who were able to specify the type of munition used and the rebel group that built it. As the Russian report has never been made public, it has been impossible to examine those claims in detail.

The report also referred to analysis of samples by the Russian government that detected Sarin:

“The United Nations Mission received from the Government of the Russian Federation its report of the results of the analysis of samples obtained from Khan Al Asal from 23 to 25 March 2013, which identified Sarin and Sarin degradation products on metal fragments and in soil samples taken at the site of the incident.

The analysis of the samples was conducted by a laboratory that has established an internationally recognized quality assurance system and performs successfully in the OPCW inter-laboratory proficiency tests. However, after the evaluation of the report, the United Nations Mission could not independently verify the information contained therein, and could not confirm the chain of custody for the sampling and the transport of the samples.”

The Syrian government failed to provide any biomedical samples from the victims taken at the time of the attack, and the mission concluded that the samples they were able to gather 5 months after the event were not useful for the investigation. While the symptoms would have been consistent with Sarin exposure, the UN mission was unable to confirm the use of Sarin, hence the conclusion that “an organophosphorous compound” was used in the attack.

Some of those seeking to blame opposition groups for the Khan al-Assal have cited an interview with Carla Del Ponte, a leading member of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, who was reported to have said that there was “strong, concrete suspicions but not yet incontrovertible proof” that opposition groups had used Sarin. Following the interview, the commission stressed that they had not reached “conclusive findings,” and their later reports would bear that out.

The 7th Report of Commission of Inquiry on Syria – A/HRC/25/65, from the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, which was published several months after the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic report, contained more information regarding the Khan al-Assal attack, along with other attacks that had taken place in the meantime. The report confirmed the use of Sarin, referring to the August 21, 2013 Sarin attack in Damscus:

“The evidence available concerning the nature, quality and quantity of the agents used on 21 August indicated that the perpetrators likely had access to the chemical weapons stockpile of the Syrian military, as well as the expertise and equipment necessary to manipulate safely large amount of chemical agents. Concerning the incident in Khan Al-Assal on 19 March, the chemical agents used in that attack bore the same unique hallmarks as those used in Al-Ghouta.”

The report concluded that in “no incident was the commission’s evidentiary threshold met with regard to the perpetrator.”

Small Scale Sarin

Following the Khan al-Assal attack, allegations of chemical weapons attacks continued. The French National Evaluation on the April 4, 2017 Khan Sheikhoun Sarin attack included an annex document listing alleged chemical attacks in Syria from 2012 to 2017, and it includes 15 chemical attacks in the period between the date of the Khan al Assal attack (March 19, 2013) and the start of August 2013. Throughout the French document, a number of attacks are highlighted in red, indicating the “Use of sarin proven by France through the collection of biomedical and/or environmental samples Attack attributed to the Syrian regime,” with three of those falling in the period between March 19, 2013 and the start of August 2013.

These attacks are of particular interest, as information gathered about the attacks were the strongest indication yet that the Syrian government had deployed Sarin in the conflict and would have implications for the understanding of future Sarin attacks.

In May 2013, Le Monde published an article, Chemical Warfare in Syria, in which journalists investigated reports of chemical weapon attacks in Damascus against opposition groups. Local fighters described the use of a device by government forces that they said were linked to these attacks:

“In the northern part of Jobar, which was struck by a similar attack, General Abu Mohammad Al-Kurdi, commander of the Free Syrian Army’s first division (which groups five brigades), said that his men saw government soldiers leave their positions just before other men ‘wearing chemical protection suits’ surged forward and set ‘little bombs, like mines’ on the ground that began giving off a chemical product. The general asserted that his men had killed three of these technicians. Where are the protection suits seized from the dead? Nobody knows… The soldiers who came under attack that night said there had been a terrible panic, with men fleeing to to the rear. There are no civilians or independent sources to confirm or deny this account: no one is left in Jobar apart from the men fighting on the neighborhood’s various fronts.”

Le Monde’s photographer even witnessed one of these attacks:

“On April 13, the day of a chemical attack on a zone of the Jobar front, Le Monde’s photographer was with rebels who have been waging war out of ruined buildings. He saw them start to cough before donning their gas masks, apparently without haste although in fact they were already exposed. Men crouched down, gasping for breath and vomiting. They had to flee the area at once. Le Monde’s photographer suffered blurred vision and and respiratory difficulties for four days. And yet, on that particular day, the heaviest concentrations of gas were used not there but in a nearby area.”

When the Le Monde team left Syria in May, they took with them samples from victims, which were tested in France, leading the French government to announce that they could confirm that Sarin was used in Jobar between April 12 and 14, stating that there was the “presence of sarin residue in blood and urine samples taken from six victims”. France was also confident in the chain of custody, stating they had “the entire chain, from the time the attack took place to the time when people were killed, and the time we took the samples, and the time we had them analysed.” Further blood, urine, hair and cloth samples provided by Le Monde were tested, leading to the conclusion that 13 victims were exposed to Sarin.

While witnesses in the Le Monde investigation described multiple types of munitions being used to deliver the chemical agents used in Damascus, the other two Sarin attacks that took place in this period were linked by the unusual method of delivery.

On the night of April 13, 2013, a chemical attack was reported in the Kurdish Sheikh Maqsoud neighbourhood of Aleppo. The attack was described by Mohammed Aly Sergie on Twitter:

“Canisters with a phosphorous type chemical, causing Sarin-like symptoms, were dropped on a home in Sheikh Maqsood on April 13 around 2 a.m. Some survivors said the canisters were dropped from a helicopter, but others didn’t hear rotors. Doctors don’t know what the chemicals were. Two children died in the attack, and their mother died later on the way to a hospital in Atme, Idlib. More than a dozen people were exposed. Survivors from Sheikh Maqsood all gave the same story today. Syria’s war is tiptoeing into the chemicals weapons phase.”

The Syrian Network for Human Rights also published details of the attack:

“Helicopter belonging to Syrian Government’s Air Force (who is owned by only Syrian Government) dropped two poison gas bombs on Sheikh Maksoud – North of Aleppo ( Kurdish majority). the bombs are metal cans fairly like conservers with plastic cans inside contains toxic materials turn into gases, it also featured with safety valves.

These bombs led to 5 victims, including two infants, more than 12 injuries cause on inhaling the poisonous gas , transferred to Afrin for treatment.”

Very little footage exists from the attack, but one video shows both the victims and the impact site:

What stands out in particular about this attack is the type of munitions used and the method of delivery. There appear to be remains of two munitions at the impact site. One, a blown apart cylinder:

Remains of a munition at the scene of the Sheikh Magsoud Sarin attack

The other munition recovered from the scene was a white grenade:

A white grenade photographed at the scene of the Sheikh Magsoud attack (source)

Also recovered from the scene were two grenade levers, almost certainly from the two munitions photographed at the scene:

Grendade levers photographed at the scene of the Sheikh Magsoud attack (source)

Based on the claims of eyewitnesses, these devices were dropped from a helicopter, and this extremely unusual method of delivery would be used in an attack two weeks later in the town of Saraqib.

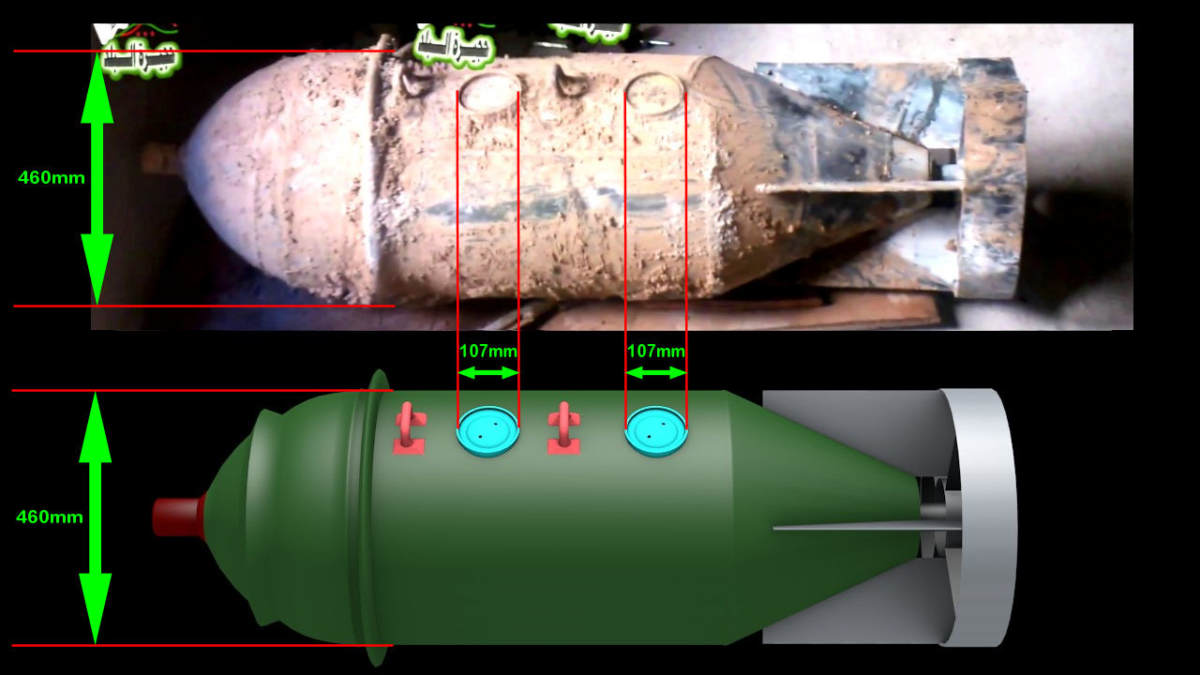

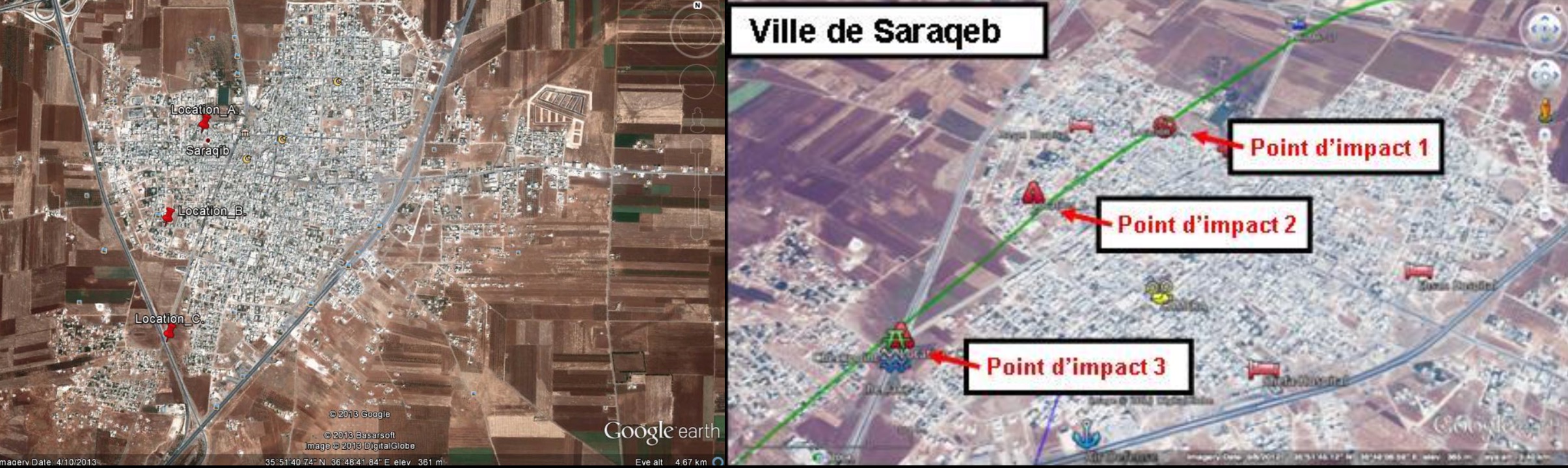

Unlike the Sheikh Magsoud attack, the Saraqib attack was investigated by a number of organisations, including the BBC, French intelligence, and the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic. The reports, and open source evidence, show a consistent version of events, with a helicopter flying across Saraqib, dropping three packages onto the town:

Maps showing the impact sites of chemical munitions in Saraqib from the UN report (left, source) and French National Evaluation (right, source)

Victims of the attack were taken to the local hospital, where they were treated for organophosphorous exposure. One victim, a 52-year-old woman, died, and her body was taken to Turkey, where 12 samples were taken from different organs and tested. These tests confirmed the use of Sarin in the attack, as reported by the UN mission.

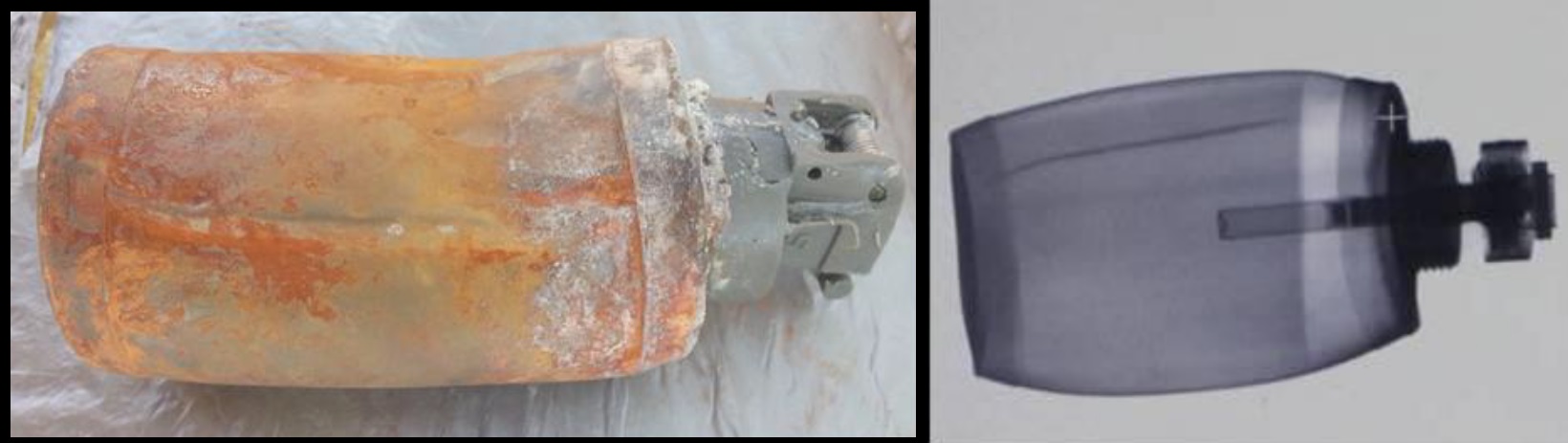

In addition to the UN mission’s investigation, the French National evaluation released after the April 4, 2017 Khan Sheikhuon Sarin attack contained details of the Saraqib attack. France had acquired an intact munition that was used in the attack, still filled with its payload:

Munition recovered from the Saraqib attack, along with its x-ray (source)

The French National evaluation described the contents of the munition:

“The chemical analyses carried out showed that it contained a solid and liquid mix of approximately 100ml of sarin at an estimated purity of 60%. Hexamine, DF and a secondary product, DIMP, were also identified. Modelling, on the basis of the crater’s characteristics, confirmed with a very high level of confidence that it was dropped from the air.”

The French National evaluation annex also highlights both these incidents as the “Use of sarin proven by France through the collection of biomedical and/or environmental samples”.

As with Sheikh Maqsoud, the devices had been dropped from helicopters, with the UN mission report providing more details of how the munitions were used:

“Allegedly tear gas and chemical weapon munitions were used in parallel. The core of the device allegedly used was a cinder block (building material of cement) with round holes. These holes could, allegedly, serve to “secure” small hand grenades from exploding. As the cinder block hit the ground, the handles of the grenades would become activated and discharged. Some of the hand grenade–type munitions allegedly contained tear gas, whereas other grenades were filled with Sarin.”

The shattered remains of what is likely the cinder block described can be seen in this video from one of the impact sites in Saraqib:

This would also explain the presence of white-grey powder at the impact site in Sheikh Magsoud, as seen below:

The impact site of the Sheikh Magsoud attack (source)

In addition, a white grenade, identical to the one seen at the scene of the Sheikh Maqsoud attack, was recovered from one of the Saraqib impact sites:

Based on the use of helicopters in the attacks, it’s extremely unlikely opposition forces would have been responsible, as they were not known to control any operable helicopters.

Volcanoes in Damascus

Following the Saraqib and Sheikh Maqsoud attacks, reports of chemical attacks continued on a regular basis, and on August 21, 2013, a massive Sarin attack was reported in the city of Damascus. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, dozens of videos were posted online, showing a chemical attack well beyond the scale of anything seen in the Syrian conflict before. Reports stated attacks had occurred in multiple locations, with hundreds killed and injured, with some estimates in the initial aftermath of the attacking being close to 2000 dead.

The initial reaction from the Syrian government was to call the allegations of a chemical attack in Damascus “baseless“:

“The source stressed that the reports circulated by the TV channels of al-Jazeera, al-Arabiya and Sky News among other channels which are involved in the shedding of the Syrians’ blood and supporting terrorism are completely baseless.

The source said the aim behind broadcasting such reports and news is to attempt to divert the UN chemical weapons investigation commission away from carrying out its duties.”

However, as open source evidence and investigations by the UN mission would clearly show, the claims were anything but baseless. In September 2013, the UN mission reported on their investigation of the attack, confirming Sarin was used. The report stated samples collected by the mission provided clear and convincing evidence surface-to-surface rockets containing Sarin were used in the Damascus districts of Ein Tarma, Moadamiyah, and Zamalka, consistent with open source evidence.

However, the mission was not tasked with identifying the perpetrators, so that question remained open, leading to a range of claims and theories about who was responsible for the attack. It would be impossible to cover every theory and allegation at length, especially as they range from the sensible to insane, but there are some aspects of the attack worth looking at in detail, as they relate to other Sarin attacks in Syria.

The rockets used in the attack were of particular interest, as two types of chemical rockets were used. In the Moadamiyah attack, a type of rocket known as an M14 140mm artillery rocket was used, a type of rocket confirmed to be in the Syrian governments inventory by a Human Rights Watch investigation, and filmed by locals after the attacks.

This is the only documented instance of this type of rocket being used in the conflict, unlike the second type of rocket used, which is known as a “Volcano” rocket:

Remains of a chemical Volcano rocket used on August 21, 2013.

Around a dozen of these rockets were reported to have been used in the attack, and their use had been documented in attacks in other opposition controlled areas, both as an explosive variant and chemical variant. Prior to the August 21, 2013 attack in Damascus, the same rockets had been filmed in the aftermath of a chemical attacks reported in Adra and Douma, Damascus, on August 5, 2013.

Local groups reported around 400 people were showing “signs of exposure to chemical toxic gases”, but the attacks drew very little international attention and were mostly forgotten about after the events of August 21st. The earliest known video of the chemical Volcano rocket, filmed in Daraya, Damascus, was published on December 26, 2012, 3 days after the first alleged Sarin attack on December 23, 2012 in Homs:

While this appears identical to the rockets used on August 21, 2013, the above video was not linked to a specific allegation of chemical weapons use.

Because of the unusual design of the rockets, it was alleged by some that these rockets were created by opposition groups as part of a false flag attack to draw foreign governments into the conflict. This hypothesis can be easily rejected, as the explosive version of the rockets are shown in use by pro-government forces in multiple videos posted online by Syrian government forces and pro-Syrian media:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5HWXqd69Vsc

A close examination of images of chemical Volcano rockets and explosive Volcano rockets show that they are virtually identical, with the only significant difference being the design of the warhead, depending on the payload. Details like the type of welding used, position, size, and arrangement of bolts, and the presence of what appears to be a fuzing-related port on the rear of the warhead are shared by both types of the munition. There is also no evidence that either type of these munitions was captured by Syrian opposition forces, and the Syrian government has told the OPCW and UN that they have not lost control of any of their chemical weapons. In a 2014 interview with CBRNe World, Ake Sellstrom, who led the UN inspections in Syria, stated the following:

“Several times I asked the government: can you explain – if this was the opposition – how did they get hold of the chemical weapons? They have quite poor theories: they talk about smuggling through Turkey, labs in Iraq and I asked them, pointedly, what about your own stores, have your own stores being stripped of anything, have you dropped a bomb that has been claimed, bombs that can be recovered by the opposition? They denied that. To me it is strange. If they really want to blame the opposition they should have a good story as to how they got hold of the munitions, and they didn’t take the chance to deliver that story.”

It would be difficult to summarise all of the various theories and allegations surrounding the August 21, 2013 attacks, and many of them are contradicted by open source analysis, but it is worthwhile examining the reactions of certain governments and notable figures.

Russia’s position on the attacks evolved over time, with the Russian Foreign Ministry initially stating that “A homemade rocket with a poisonous substance that has not been identified yet – one similar to the rocket used by terrorists on March 19 in Khan al-Assal – was fired early on August 21 [at Damascus suburbs] from a position occupied by the insurgents.” The Russian government specifically identified the exact type of rocket used in Khan al-Assal and which opposition group uses it: a “Basha’ir-3” unguided projectile launched by the “Basha’ir al-Nasr” brigade affiliated with the Free Syrian Army. However, the open source evidence indicates Volcano rockets used by Syrian government forces were the only “homemade” projectiles used in the attack.

“More new evidence is starting to emerge that this criminal act was clearly provocative. On the internet, in particular, reports are circulating that news of the incident carrying accusations against government troops was published several hours before the so-called attack. So, this was a pre-planned action.”

This appears to have referred to multiple reports at the time that some of the videos supposedly posted on August 21st appeared with a date of August 20th, as reported by a number of sites, with those claims being republished by sites such as Russia Today, and Voice of Russia. The below image from Islamic Invitation Turkey was used by Voice of Russia (now Sputnik) in their coverage:

This conclusion is based on a misunderstanding of how YouTube dates videos. The displayed dates of YouTube videos are based on the location of the YouTube servers in the US, so if a video is uploaded early in the morning in Syria then the time in the US is towards the end of the previous day. It’s possible to check the exact time a YouTube video was uploaded using Amnesty International’s YouTube Dataviewer, and a review of all the videos posted on YouTube showing the events of August 21, 2013 but displaying a date of August 20, 2013 shows they were in fact uploaded on the morning of August 21st in Syria.

On August 25th the Russian Foreign Ministry urged against “hurried conclusions“, stating:

“We strongly urge those who, in trying to impose their opinion on U.N. experts ahead of the results of an investigation, announce the possibility of military action against Syria, to exercise discretion and not make tragic mistakes.”

Following that statement Russia’s Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, held a press conference, and referenced the now discredited claims about YouTube upload times: “There is information that videos were posted on the internet hours before the purported attack, and other reasons to doubt the rebel narrative,” adding “Those involved with the incident wanted to sabotage the upcoming Geneva peace talks. Maybe that was the motivation of those who created this story. The opposition obviously does not want to negotiate peacefully.”

On August 29th, the small independent media organisation Mint Press published a piece, Syrians In Ghouta Claim Saudi-Supplied Rebels Behind Chemical Attack, which the Russian foreign ministry would cite in a number of future statements. The article claimed that “rebels received chemical weapons via the Saudi intelligence chief, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, and were responsible for carrying out the dealing gas attack.”

The article generated a great deal of controversy, not least for its content. One of the two claimed authors, Dale Gavlak, distanced herself from the article, claiming her contribution to the article was editing non-native speaker Yahya Ababneh’s use of English, and helping Yahya pitch it to Mint Press. She claimed she clearly told Mint Press “this should go under Yahya Ababneh’s byline. I helped him write up his story but he should get all the credit for this.” As her reputation was used to give the article by the virtually unknown Ababneh credibility, the controversy brought the content of the article into doubt.

As for the article itself, the claims of rebel involvement in the August 21st attack were quite thin. It describes an accident in tunnels releasing chemicals, killing a number of rebels in the area, but it doesn’t claim this event and the August 21st attack were linked. In fact, only the headline and the following section make any reference to the August 21st attack:

“However, from numerous interviews with doctors, Ghouta residents, rebel fighters and their families, a different picture emerges. Many believe that certain rebels received chemical weapons via the Saudi intelligence chief, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, and were responsible for carrying out the dealing gas attack.”

Beyond the headline and that one paragraph, there are no further claims that the rebels were responsible for the August 21st attack and certainly none of the quotes from locals linked the rebels to the August 21st attack. This didn’t stop it from becoming part of Russia’s ongoing attempts to blame the opposition for the August 21st attack.

On September 16, Russia’s Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, came out with more claims about the August 21st attack, dropping the earlier claims of YouTube videos being uploaded before the attack took place.

“There is lots of evidence delivered by independent experts onsite [a nun from a local convent, other eyewitnesses and Western reporters] and European and U.S. experts, including twelve retired officers of the Pentagon and the CIA who sent an open letter to President Barack Obama to explain how the case had been falsified, unfortunately, a lot had been done before the St. Petersburg meeting by bad people who used poisonous chemical substances largely, in our opinion, to provoke a retaliation strike against the regime and shifted the responsibility for the use of chemical weapons, although that was totally illogical and Russian President Vladimir Putin said so many times.”

In later comments made on September 22, Lavrov was reported to have said:

“Evidence given by witnesses and journalists showed that rebels acquired “some shells from abroad that they had never seen and had no idea of how to use them, and then finally they used them,” Lavrov said.”

Lavrov repeated these claims in a September 25th interview with the Washington Post:

Russia is still saying that it was the rebels who fired the chemical weapons on Aug. 21 — not the Assad regime? Yes, we believe there is very good evidence to substantiate this.

Are you willing to present this evidence? Yes, I just presented a compilation of evidence to John Kerry when we met a couple of hours ago. This evidence is not something revolutionary. It’s available on the Internet. They are reports by journalists who visited the sites and talked to the combatants, who said they were given some unusual rockets and ammunition by some foreign country and they didn’t know how to use them. There is also evidence from the nuns living in the monastery nearby who visited the site. You can read the assessments by the chemical weapons experts who say that the images shown do not correspond to a real situation if chemical weapons were used. And we also know about the open letter sent to President Obama by former operatives of the CIA saying the assertion that the [Syrian] government used chemical weapons was fake. So you don’t need to have any spy reports to make your own conclusions, you only need to carefully watch what is available in public.

It appears that, aside from Yahya Ababneh’s Mint Press article, no other journalists had claimed to have visited the site at that time, and the story of combatants who were “given some unusual rockets and ammunition by some foreign country and they didn’t know how to use them” is consistent with the Mint Press story. It seems clear Lavrov repeatedly referred to the Mint Press article, which had become increasingly controversial by the day.

Lavrov and the Russian foreign ministry also repeatedly referred to “nuns living in the monastery nearby who visited the site.” This appears to have been referring to the controversial nun Sister Agnes Mariam de la Croix, who had made a number of statements prior to the August 21, 2013 Sarin attacks supporting the Syrian government, including claiming the Syrian opposition were responsible for the notorious Houla massacre, and has been described as:

“According to the Swiss newspaper Le Courrier, Agnès-Mariam was “comfortable among [Assad’s] security services,” and she told their reporter it was hoped he could “dismantle the propaganda of Western media.””

On September 6, she was interviewed by Russia Today (‘Footage of chemical attack in Syria is fraud’), and made a number of claims about the attack, which were later repeated in a 50-page report her organisation prepared. According to a BBC report on her work, her report asked:

- Ghouta, the main area to the east of Damascus which came under attack, was already “deserted”, so why were there were so many civilian casualties?

- Why are so many children seen in the videos without their parents? There is “a flagrant lack of real families”

- Why are there so few women in the videos and why are so many people unidentified?

- Why is there so little evidence of burials?

- There were tens of thousands of civilians trapped in the Ghouta area of Damascus, according to very regular reports received by Human Rights Watch

- Children were often sleeping in the basements of buildings in significant concentrations because of the intense shelling and that is why so many died (Sarin gas accumulates at low levels)

- The dead and those injured in the chemical attack were moved from place to place and room to room both at the clinics and ultimately for burial

- There were many men and women who were victims of the attacks. But there were separate rooms for the bodies of children, men and women so they could be washed for burial

- Almost all of the victims have been buried

- Human rights researchers have spoken to the relatives of Alawite women and children abducted by rebels. None of them said they had recognised their loved ones in the gas attack videos

“Lavrov then cited an open letter sent to President Obama by former operatives of the CIA that cites the Mint Press report and states that they are “unaware of any reliable evidence that a Syrian military rocket capable of carrying a chemical agent was fired into the area.”

The UN chemical inspectors investigation described the size and structure of two rocket delivery systems used and report the direction some of the rockets likely came from. The report doesn’t ascribe blame but present evidence that is damning for Assad.”

In addition to these claims, Lavrov, speaking on October 1, 2013, referred to the earlier Khan Al Assal attack:

“We have no doubt that sarin gas – which was used on March 19 in Aleppo, is home-made… We also have information to corroborate that in the course of the tragic events of August 21, when chemical weapons were used, sarin gas of a very similar chemical signature to the one on March 19, was used, but of a much higher concentration “

Again, a Khan al-Assal link, but instead of claiming the same type of rocket was used in both attack, Lavrov now claimed it was Sarin with a very similar chemical signature. Not only that, it was home-made Sarin, and following the logic of his earlier claims, this is home-made Sarin was made by the Saudis and was provided to the Syrian opposition in Damascus, and therefore must have also been provided to the opposition for the Khan al-Assal attacks. If true, this would have implicated the Saudis in not only the August 21st attack, but also the earlier Khan al-Assal attack, a hugely significant accusation. On October 4, Interfax reported:

“A group sent by Saudi Arabia from Jordanian territory is responsible for the August 21 chemical weapons provocation that was staged in the Eastern Ghouta suburb of Damascus, Russian diplomatic sources told Interfax.

“Having analyzed this information, which was received from a whole range of sources, we are getting the picture confirming that the criminal provocation in Eastern Ghouta was committed by a specialized group that was sent by Saudi Arabia from the territory of Jordan and acted under the cover of the Liwa al-Islam group,” one of the sources said.”

Despite the claimed linked between the Sarin used in the Khan al-Assal attack and the Eastern Ghouta attack, based on the Russian statements it must have been two different groups responsible, because when they submitted their report on the Khan al-Assal attack to the UN, they stated:

It was determined that on March 19 the rebels fired an unguided missile Bashair-3 at the town of Khan al-Assal, which has been under government control. The results of the analysis clearly show that the shell used in Khan al-Assal was not factory made and that it contained sarin

And that:

According to Moscow, the manufacture of the ‘Bashair-3’ warheads started in February, and is the work of Bashair al-Nasr, a brigade with close ties to the Free Syrian Army.

The Russian claims about the homemade Sarin were called into question by the 7th Report of Commission of Inquiry on Syria – A/HRC/25/65:

“The evidence available concerning the nature, quality and quantity of the agents used on 21 August indicated that the perpetrators likely had access to the chemical weapons stockpile of the Syrian military, as well as the expertise and equipment necessary to manipulate safely large amount of chemical agents. Concerning the incident in Khan Al-Assal on 19 March, the chemical agents used in that attack bore the same unique hallmarks as those used in Al-Ghouta.”

“Interviewer – Why was hexamine on the list of chemical scheduled to be destroyed – it has many other battlefield uses as well as Sarin? Did you request to put it on the list or had the Syrian’s claimed that they were using it?

Sellstrom – It is in their formula, it is their acid scavenger.”

Ron Manley, a chemical arms expert who headed the verification team at the OPCW from 1993 to 2002, was asked by the New York Times to give his opinion on the presence of hexamine in the list:

“The fact that they declared it to the OPCW means it was part of their CW program. There’s no doubt it was part of their program. What part it played we don’t know.”

Chemical weapons specialists Dan Kaszeta explained the significance of hexamine and its use as an acid scavenger in his 2014 article The Chemical Fingerprint of Assad’s War Crimes:

“With assistance of others, I have worked out at least one process that would produce Sarin using this method, but it would be dangerous, unethical, and possibly illegal to publish such a process. Hexamine is not previously noted in the open literature for use in Sarin production, although it should be stated that the large majority of knowledge of the manufacture of chemical warfare agents is not freely available and much of this information is classified. The use of other amines is known. The U.S. nerve agent production program, at various points, used amines, such as tributylamine (U.S. stockpile Sarin contained an average of nearly 2% tributyalamine) and isopropylamine (used in the U.S. M687 binary Sarin artillery shell) to deal with acid.

Hexamine was likely used by the Syrians for the same general purpose – scavenging acid. Hexamine can bind with up to four HF molecules, is cheap, is easily produced, is less of a fire hazard, has longer shelf life, and does not set off alarms in nonproliferation circles, unlike, say, tributylamine which is tracked on watch lists.”

What was not made public until the after the April 4, 2017 Sarin attack on Khan Sheikhoun, where hexamine was also detected in multiple samples, is that French intelligence had acquired an unexploded munition used in the 2013 attack on Saraqib (described above). The French National evaluation published after the 2017 Khan Sheikhoun attack described the contents of the unexploded munition:

“The chemical analyses carried out showed that it contained a solid and liquid mix of approximately 100ml of sarin at an estimated purity of 60%. Hexamine, DF and a secondary product, DIMP, were also identified.”

The only reasonable explanation for the presence of hexamine in the fill of an unexploded munition is that it was being used as an acid scavenger, and the presence of hexamine links the August 21, 2013 Sarin attack to the 2013 Saraqib attack and 2017 Khan Shiekhoun attack.

Despite the use of rockets only known to be used by the Syrian government and presence of hexamine, there were still those who preferred other scenarios. The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Seymour Hersh presented his own version of events, garnered from unnamed sources. Hersh described the involvement of the Turkish government and the Syrian Jihadist opposition group Jabhat al-Nusra in the attack, a false flag which attempted to draw the US into the conflict.

However, analysis of the open source evidence demonstrates many issues with Hersh’s story, including questions about the practicalities of manufacturing Sarin in the quantities used on August 21 and the prior use of Volcano rockets by the Syrian government, none of which Hersh was able to provide a satisfactory answer for. Despite this, for many, Hersh’s version of events became their preferred narrative around what happened on August 21, 2013, despite the clear issues with Hersh’s claims.

The Rebels’ Revenge?

In the days following the attack, the Syrian government made multiple allegations of chemical weapon use by opposition groups in and around Damascus. The attacks, which the Syrian government said had taken place on August 22 in Bahhariyeh, August 24 in Jobar, and August 25 in Ashrafiah Sahnaya, were investigated by the United Nations Mission, and in the Jobar and Ashrafiah Sahnaya cases environmental and medical samples provided by the Syrian government, and one sample by the UN Mission, indicated the presence of Sarin. In the case of the August 22nd attack in Bahhariyeh, the UN Mission report on the attack stated:

“In the absence of any positive blood samples, the United Nations Mission cannot corroborate the allegation that chemical weapons were used in Bahhariyeh on 22 August 2013.”

The August 24th Jobar incident was described in the UN report:

“On 28 August 2013, the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic reported to the Secretary General that at 1100 hours on 24 August 2013, as a group of soldiers approached a building near the river in Jobar, they heard a muffled sound and then smelled a foul and strange odour, whereupon they experienced severe shortness of breath and blurred vision. Four of them were immediately taken to Martyr Yusuf Al Azmah Military Hospital to receive emergency care. The Government further reported that in its search of the buildings immediately surrounding the above-mentioned site, it discovered some materials, equipment and canisters, examination of which indicated that they contained Sarin.”

The location of the incident was also published in the report, just south of territory that had been captured by Syrian government forces ahead of the August 21st Sarin attacks, where Volcano rockets had targeted locations just 1.5km to the south of the Jobar August 24th incident. Satellite imagery from the location taken on the day of the attack shows Syrian government armoured vehicles just a few hundred meters away from the reported location of the August 24th incident:

Locations of armoured vehicles in relation to the August 24th attack site. Satellite image from August 24, 2013

The Syrian government also provided the remains of the IED they claimed was used in the attack, which had not been previously seen in the conflict, nor since:

On the same day as the attack, Syrian government forces were also reported to have discovered an opposition chemical weapons stockpile, which contained two unexploded munitions of the type used in the August 24th Jobar attack:

Left – IEDs captured by Syrian government forces; Right – The IED featured in the UN report on the August 24th Jobar attack

Dr Jean Pascal Zanders, who specialises in the field of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear weapons, stated the munitions were filled with Sarin and hexamine, stating “the filling displayed all the characteristics of sarin as produced by the Syrian government, the principal telltale sign being the presence of hexamine (hexamethylenetetramine).” This information is not available in any public source as Zanders states the “hexamine presence was confirmed in several discussions I have had over the past two months with people closely following the Syria dossier, including government officials, diplomats and scientists.”

The UN Mission report went on to state:

“The United Nations Mission, however, could not independently verify the information received, therefore, it did not establish the provenance of the IEDs and could not link them to the location of the alleged use.”

Issues with the chain of custody were also present with environmental samples:

“While the United Nations Mission visited the site, it found the site to have been corrupted by mine-clearing activities. As such, there was no probative value in collecting samples.

The Syrian Government allegedly recovered soil samples from the impact site that tested positive for Sarin. The United Nations Mission could not verify the chain of custody for this sampling and subsequent analysis.”

Biomedical samples from the four victims provided by the Syrian government and taken under the supervision of the UN Mission a month after the attack were tested, with the Syrian government samples all testing positive for indicators for Sarin, and one of the UN Mission’s samples testing positive for the indicators of Sarin. The UN Mission report concludes:

“The United Nations Mission collected evidence consistent with the probable use of chemical weapons in Jobar on 24 August 2013 on a relatively small scale against soldiers.

However, in the absence of primary information on the delivery system(s) and environmental samples collected and analysed under the chain of custody, the United Nations Mission could not establish the link between the victims, the alleged event and the alleged site.”

The August 25th attack in Ashrafiah Sahnaya was described in the UN Mission report:

“..cylindrical canisters were fired using a weapon that resembled a catapult at some soldiers in the Ashrafiah Sahnaya area in Damascus Rif. One of

the canisters had exploded, emitting a sound of medium loudness. A black, foul-smelling smoke had then appeared, causing the soldiers blurred vision and severe shortness of breath. Five of them had been immediately taken to Martyr Yusuf Al Azmah Military Hospital to receive emergency care.”

The UN Mission was unable to visit the site, nor were the remains of the munition reportedly used presented to the mission, which drew the following conclusions based on biomedical samples and interviews with the soldiers involved in the incident:

“The United Nations Mission collected evidence that suggests that chemical weapons were used in Ashrafiah Sahnaya on 25 August 2013 on a small scale against soldiers. However, in the absence of primary information on the delivery system(s) and environmental samples collected and analysed under the chain of custody, and the fact that the samples collected by the United Nations Mission one week and one month after the alleged incident tested negative, the United Nations Mission could not establish the link between the alleged event, the alleged site and the survivors.”

It is important to note that, as with other attacks investigated by the United Nations Mission in Syria, including the Khan al Assal attack, Saraqib attack, and the August 21, 2013 attack, the United Nations Mission was not tasked with placing blame for the three attacks described above.

Khan Sheikhoun

In the years following the August 21, 2013 chemical attacks, reports of chemical attacks continued, the vast majority of which involved chlorine use by Syrian government forces, usually in munitions deployed from helicopters, or chemical attacks by ISIS. Until the April 4, 2017 Sarin attack on Khan Sheikhoun, there were no solid allegations of Sarin use in the conflict after the August 21, 2013 attack, although it is notable that reported chemical attacks in Latamneh, Hama on March 30, 2017 and Uqairabat, Hama on December 12, 2016 were described in the annex of the French National Evaluation on the April 4, 2017 Khan Sheikhoun Sarin attack as having a “strong presumption of use of sarin by the Syrian regime.” However, these incidents have not been investigated by the OPCW, nor is there a significant amount of open source evidence that would strongly indicate the use of Sarin in those attacks.

On the morning of April 4, 2017, reports began to surface on social media of an attack on Khan Sheikhoun. The previous weeks had seen multiple allegations of chemical weapon use by the Syrian government, generally reported as the use of chlorine gas, so initially it was assumed this was another chlorine attack. However, videos, photographs, and reports on social media soon made it clear this was not the chlorine gas attack people had come to expect, but had all the signs of a nerve agent attack. Claims about the attack coming from the ground generally described the same scenario: a Syrian government aircraft dropping a bomb filled with the chemical around 7am in the morning, local time:

“On 4th April 2017, Khan Al Shekhoun was targeted with 4 rockets by two airstrikes from Sukhoi 22. The civil defense was at the impact site that was targeted with chemical gas. The civil defense were injured. More than 200 injured people were moved to medical clinics. we don’t know exactly the number of casualties but we believe it’s more than 50 or 60 casualties. The medical team took off cloths from injured people, wash their bodies with water and them getting them inside the medical points. The symptoms were, respiratory distress described as a tightness, yellow foam material coming out from their mouth, and also later on blood came out of the mouth as well.”

1:18 – “Many cases of suffocation are coming to us as a result of gas attacks. Children and women were among the injured. We received more than 70 casualties and 20 casualties so far. We don’t know what kind of gas was used.”

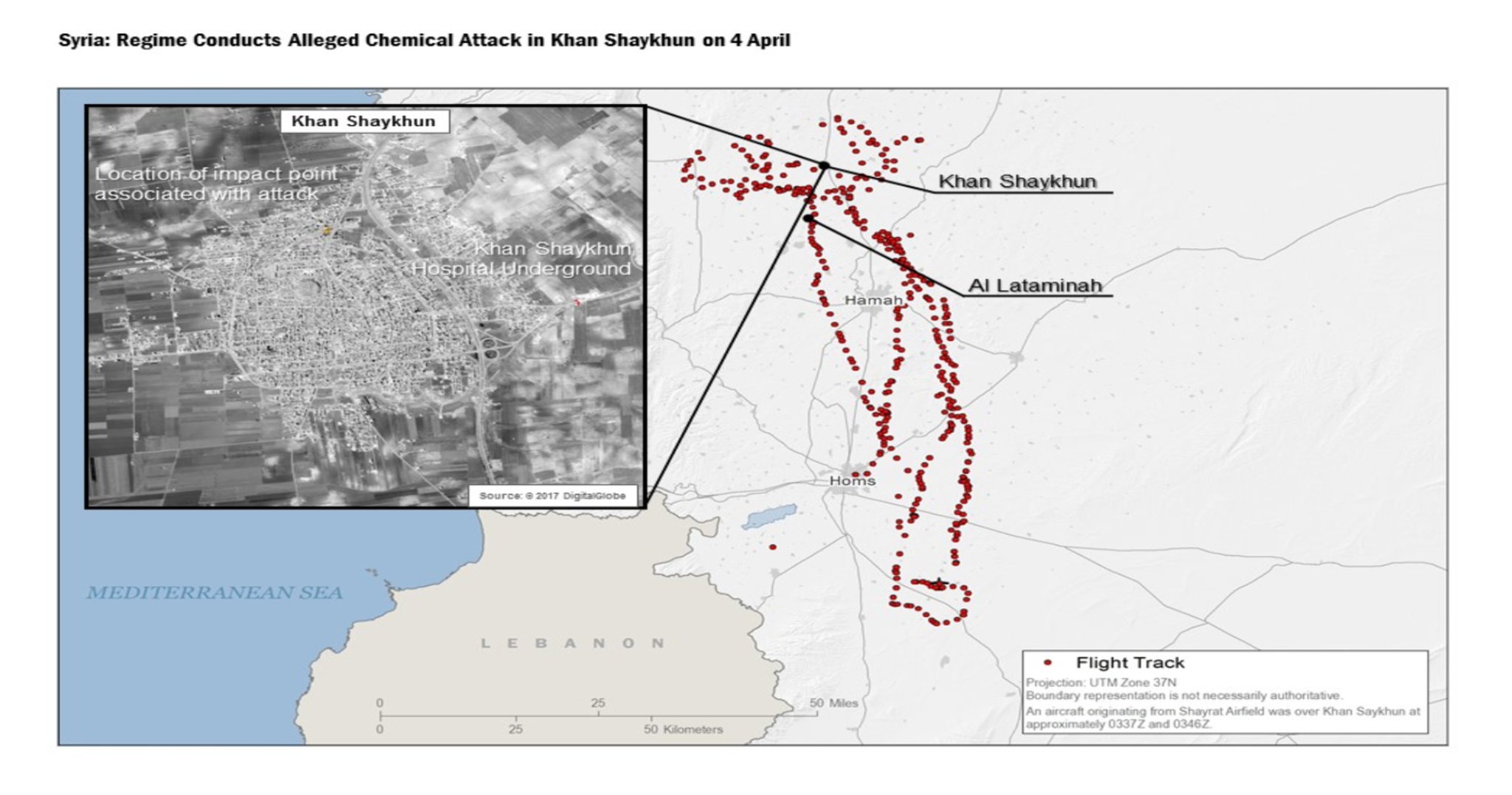

As with previous chemical attacks, differing scenarios about the attack were presented by the various factions involved with the conflict. Initially, the Syrian and Russian governments spoke about a chemical weapons warehouse in the east of Khan Sheikhoun being bombed by their forces, although it was quickly noted that the time they gave for that attack was hours after the first report of the attack, and neither the Russian nor Syrian government have presented any evidence to support their case, instead attacking the credibility of investigations into the attack and attacking the reliability of reports from the ground. The US government presented a flight path of the aircraft they claim bombed Khan Sheikhoun, with the impact site, time of attack, and airbase of origin for the attack consistent with reports from the ground:

The French National Evaluation went one step further, claiming analysis of Sarin used in the 2013 Saraqib attack matched environmental samples collected at one of the impact points in Khan Sheikhoun, revealing the presence of Sarin as well as “a specific secondary product (diisopropyl methylphosphonate – DIMP) formed during synthesis of sarin from isopropanol and DF (methylphosphonyl difluoride),” and hexamine. This was consistent with the findings of the OPCW Fact Finding Mission (FFM), which confirmed the presence of Sarin and hexamine in environmental samples collected from the impact site provided by both opposition groups and the Syrian government.

Again, the Pultizer Prize-winning journalist Seymour Hersh presented his own version of events. In Trump‘s Red Line, Hersh states, “The available intelligence made clear that the Syrians had targeted a jihadist meeting site,” and the target “was depicted as a two-story cinder-block building in the northern part of town.”

Hersh states Russian intelligence established “that a high-level meeting of jihadist leaders was to take place in the building, including representatives of Ahrar al-Sham and the al-Qaida-affiliated group formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra.”

According to the article, Russian intelligence described the building as “a command and control center that housed a grocery and other commercial premises on its ground floor with other essential shops nearby, including a fabric shop and an electronics store.” In addition:

The basement was used as storage for rockets, weapons and ammunition, as well as products that could be distributed for free to the community, among them medicines and chlorine-based decontaminants for cleansing the bodies of the dead before burial. The meeting place – a regional headquarters – was on the floor above. “It was an established meeting place,” the senior adviser said. “A long-time facility that would have had security, weapons, communications, files and a map center.” The Russians were intent on confirming their intelligence and deployed a drone for days above the site to monitor communications and develop what is known in the intelligence community as a POL – a pattern of life. The goal was to take note of those going in and out of the building, and to track weapons being moved back and forth, including rockets and ammunition.

Hersh describes the attack on the “jihadist meeting site” as being performed by a Syrian SU-24, armed with a “Russian-supplied guided bomb equipped with conventional explosives.” Hersh states that, as a result of that attack, chemical agents were released that resulted in the casualties seen on April 4.

However, not only does the OPCW FFM’s report disagree with these claims, but the French, US, Russian, and Syrian claims all contradict Hersh’s version of events. When asked for evidence to support his version of events, Hersh simply stated that he “learned just to write what I know, and move on.”

More recently, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic reported that their own investigation into Khan Sheikhoun had concluded:

“In view of the above, the Commission finds that the claim that airstrikes hit a depot producing chemical munitions or that the attack was fabricated are not supported by the information gathered. On the contrary, all evidence available leads the Commission to conclude that there are reasonable grounds to believe Syrian forces dropped an aerial bomb dispersing sarin in Khan Shaykhun at around 6.45 a.m. on 4 April. The use of chemical weapons is unequivocally banned under international humanitarian law. The use of sarin in Khan Shaykhun on 4 April by Syrian forces constitutes the war crimes of using chemical weapons and indiscriminate attacks, and violation of the prohibition on the use of weapons designed to cause superfluous injury and unnecessary suffering. The manufacture, storage, and use of sarin also violates the Chemical Weapons Convention and Security Council resolution 2118 (2013)”

The report also referenced the presence of hexamine in samples gathered the OPCW-FFM from opposition groups and the Syrian government:

“The presence of hexamine was not further explained by the OPCW FFM, but the chemical had also been found in environmental samples collected 2013 after the Ghouta incident. Two competing explanations have been offered in the past to explain the presence of hexamine — either the chemical might indicate the use of an artisanal explosive (RDX) for agent dispersion, or it had been used in the sarin synthesis as an acid scavenger. While the former explanation cannot be ruled out, the latter would be consistent with the chemicals declared by Syria in 2013 to the OPCW as part of their chemical weapons stockpile, as well as with the process used in the past by the Syrian army for employing sarin (binary synthesis shortly before use without subsequent purification of the agent for long-term storage).”

The final sentence is of particular note, highlighting the use of hexamine by the Syrian army in its deployment of Sarin, consistent with Ake Sellstrom’s statement of hexamine’s use as an acid scavenger by the Syrian government. It’s also worth noting the RDX theory would not account for the presence of hexamine in the unexploded munition from the 2013 Saraqib attack.

The Future

With the publication of the OPCW-FFM report on the Khan Sheikhoun Sarin attack, the next major report that is expected is an OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism report on the Khan Sheikhoun Sarin attack in October 2017, which will hopefully shed more light on the perpetrators of the attack. Previously, the OPCW-UN JIM has only confirmed the use of chlorine by Syrian government forces and sulfur mustard by ISIS, so if they do confirm the use of Sarin by the Syrian government, it would be very significant. However, despite their earlier reports confirming the use of chlorine by the Syrian government, efforts to bring the government to account have been blocked by Russia and China, so what action the UN would take is currently unclear.