Khan Sheikhoun, or How Seymour Hersh "Learned Just to Write What I Know, And Move On"

Following the July 4th, 2017 publication of the OPCW fact-finding mission (FFM) report on the April 4th, 2017 Khan Sheikhoun Sarin attack in Syria, questions were raised about claims made by the veteran journalist Seymour Hersh in his June 25th, 2017 article in Welt, “Trump‘s Red Line“.

The OPCW FFM report flatly contradicted claims made in Hersh’s article, namely how a Syrian SU-24 supposedly fired a precision-guided munition at a Jihadi command and control center in the north of Khan Sheikhoun, with the resulting explosion inadvertently releasing toxic gases from “medicines and chlorine-based decontaminants” stored in the basement of the building, along with unspecified weapons and munitions.

Hersh’s claim contradicted the OPCW FFM report, which stated that Sarin had been detected in environmental samples and in tests on the victims of the attack. Not only that, but Hersh’s reporting also contradicted claims made by the US, French, Syrian, and Russian governments.

Until July 26th, both Welt and Hersh have been quiet about the obvious contradictions between their claims and the OPCW FFM report. This changed when Charles Davis, editor at ATTN.com, emailed Hersh and asked him to comment on the fact the OPCW FFM report contradicted his claims published in Welt.

Here's my full correspondence with Sy Hersh. pic.twitter.com/4N8HwEkpvx

— Charles Davis (@charliearchy) July 28, 2017

Hersh offered no defence of his work, stating that he had “learned just to write what I know, and move on”, and recommended that Davis contact two individuals: Ted Postol, and former UNSCOM inspector Scott Ritter.

With Hersh now offering up Postol and Ritter, it is worth reviewing their statements on the chemical attack, and seeing if they offer any information that supports the claims made by Hersh in Welt.

Ted Postol, professor emeritus of Science, Technology, and International Security at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), has become rather notorious among those who follow the conflict in Syria after his work with the late Richard Lloyd on the August 21st, 2013 Sarin attacks. During his work on the attacks with Lloyd, he analysed the ranges of the rockets used in the attacks, and came to believe, based on maps published by the White House of areas of control in Damascus, that the range of the rockets would have required them to have been launched from rebel territory, the implication being that the attack was therefore a false flag carried out by the rebels to blame the Syrian government.

While open source evidence clearly showed government forces would in fact have been in recently captured territory within the 2-2.5km range Postol and Lloyd proposed for the rockets, Postol continued to promote his theories, and gained particularly notoriety when he sought expertise on chemical weapons not from the MIT chemical engineering department or experts in the field of chemical weapons, but Maram Susli, also known as Partisangirl or Syrian Partisan Girl, a chemistry student in Australia best known for her YouTube videos detailing conspiracy theories and her support of the Syrian government.

Following the April 4th, 2017 attack in Khan Sheikhoun, Postol released a series of reports about the chemical attack. These reports were widely cited by conspiracy websites and Russian news sites, such as Russia Today and Sputnik, and were even referenced by Alexander Yakovenko, Russian Ambassador to the United Kingdom, in his attacks on the OPCW FFM report. However, despite publishing nearly a dozen reports on the subject, there was little interest in them from the mainstream media.

While many of Postol’s supporters claimed this lack of interest was just another sign of the mainstream media’s bias against Syria and Russia, it is more likely that the poor quality of his work — both with the August 21 Sarin attack and the Khan Sheikhouna ttack — was responsible for the lack of coverage.

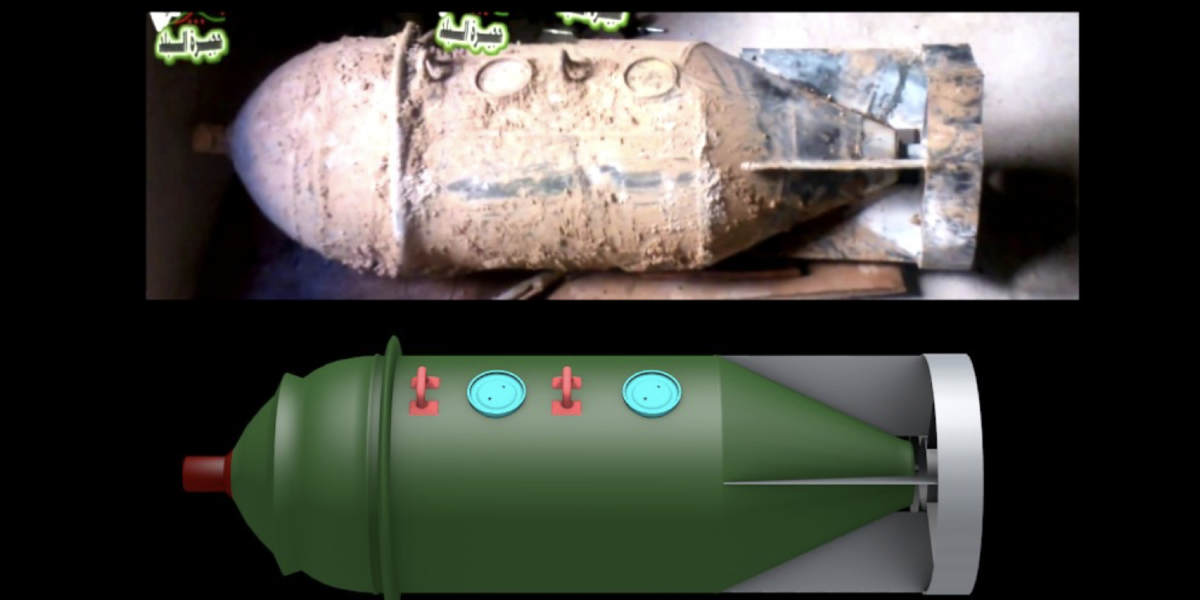

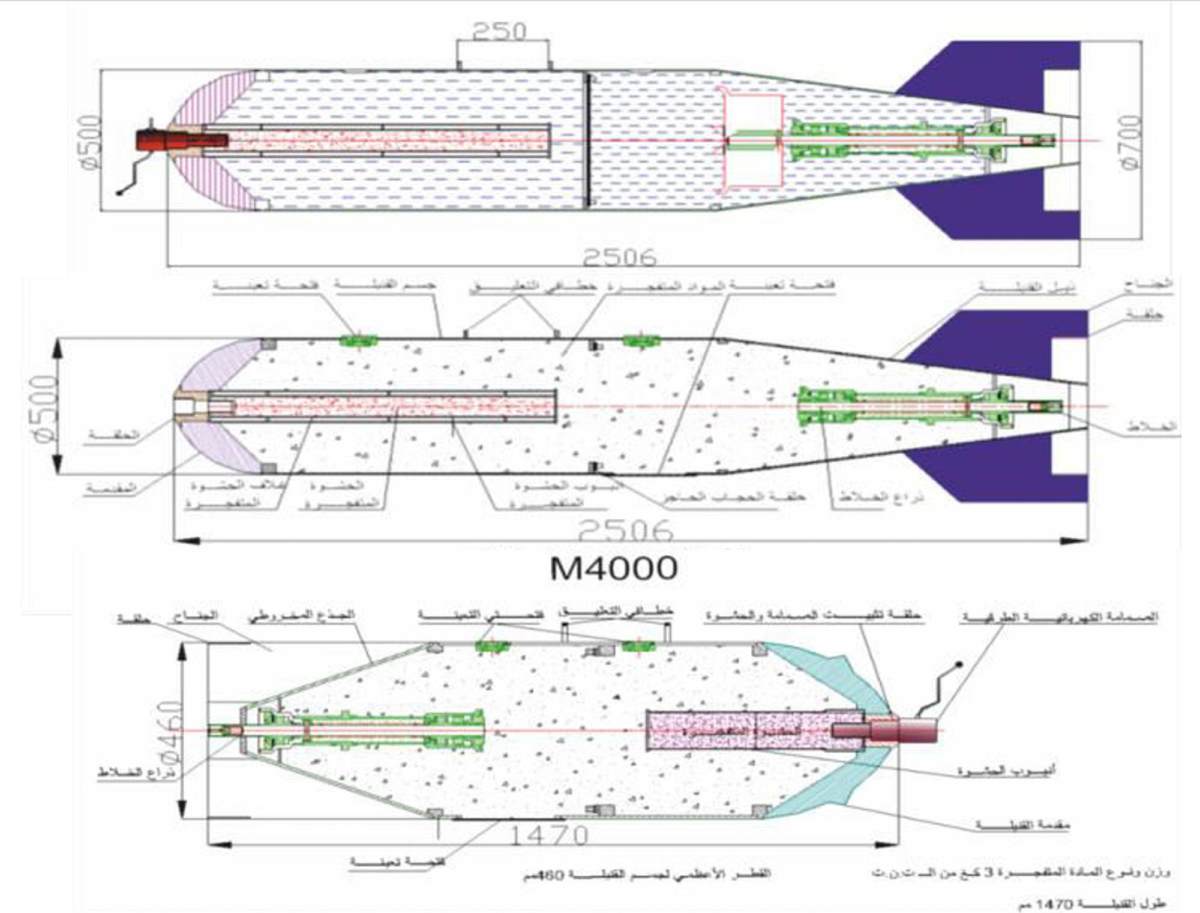

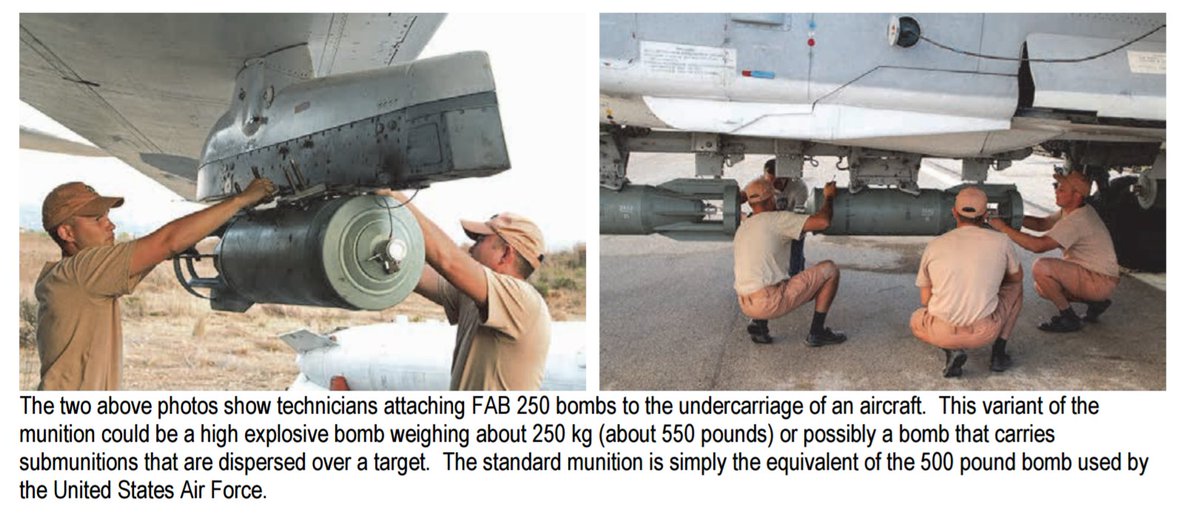

Postol’s reports on Khan Sheikhoun are riddled with errors. For example, in his report “The Human Rights Watch report cites evidence that disaffirms its own conclusions about the alleged nerve agent attack at Khan Sheikhoun in Syria”, Postol makes multiple errors when describing munitions. Firstly, he misidentifies OFAB 250-270 bombs as FAB-250s:

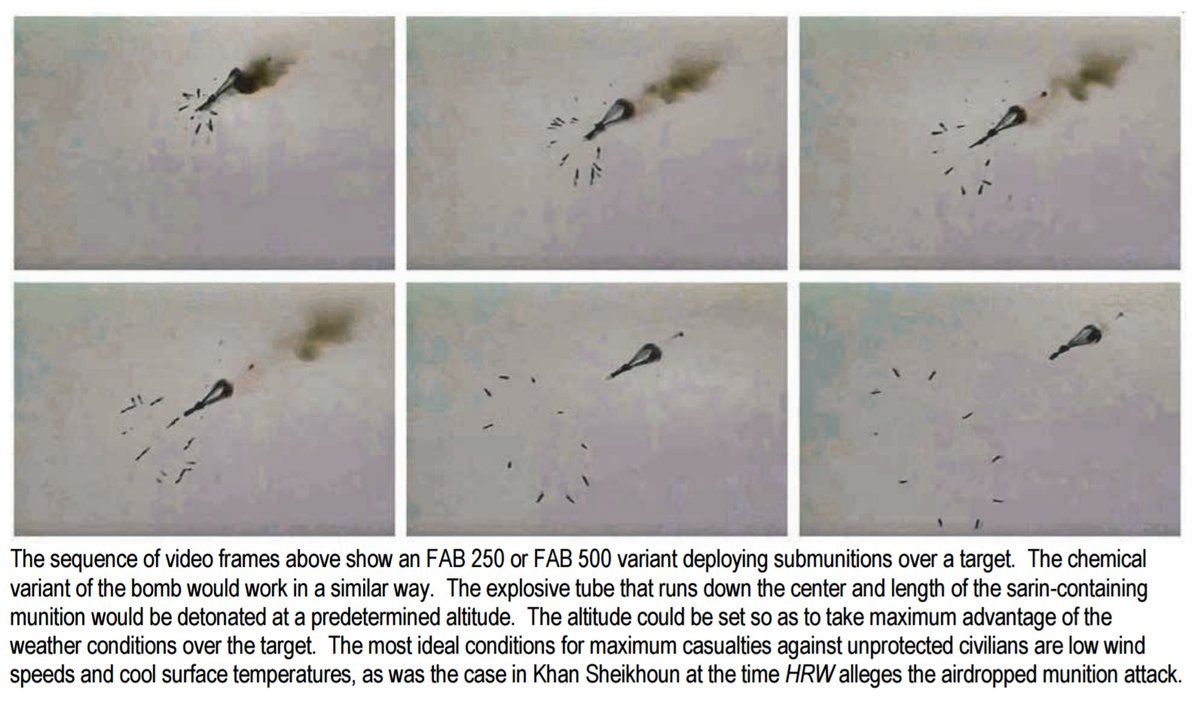

He then describes a RBK-500 BetAB cluster bomb as either a FAB 250 or FAB 500:

These may seem like relatively minor issues, but it demonstrates the unreliability of his work for a supposed weapons expert to make elementary errors regarding these bombs, particularly when discussing the precise nature of the munition used in the Khan Sheikhoun attack. This would not be entirely damning if this was the only error in his reporting, but his other reports contain other basic errors.

In another report, The Nerve Agent Attack that Did Not Occur, April 19, Postol claims the wind direction, and the resultant spread of Sarin from the impact site, was inconsistent with the claimed casualty figures, and was evidence that the claims around the attacks were lies.

Shortly afterwards, Postol published his next report IMPORTANT CORRECTION TO The Nerve Agent Attack that Did Not Occur, April 21, where he admitted he had got the early wind direction completely wrong, but reassured his readers it still meant there was something fishy about the attack.

In fact, when the OPCW report was released, they stated the movement of the Sarin was influenced more by the terrain than wind:

“The descending nature of the terrain from the initiation point and the distribution of the casualties support the promulgation of a chemical denser than air, which followed the slightly descending nature of the hill towards lower areas towards the West and South West of the likely initiation location, and along a street descending from the hill in a southerly direction.”

Along with the above statement, they also published a map showing the locations of casualties, the location of which matched neither map based on wind direction presented by Postol:

As a final example, Postol’s report The French Intelligence Report of April 26, 2017 Contradicts the Allegations in the White House Intelligence Report of April 11, 2017 contained an error that totally undermines the credibility of Postol as a serious investigator.

In this report, Postol claims that a report published by the French government detailing their reasoning behind linking the Syrian government to the Khan Sheikhoun attack directly contradicts the US claims about the attack. Postol states that the French claimed the attack was not by jets dropping bombs in Khan Sheikhoun, as the Americans claimed, but by helicopters dropping grenades filled with Sarin over the town of Saraqib.

There is, however, one pretty big problem with Postol’s report. In his excitement to debunk another White House narrative, he had somehow not realised the French report was comparing the 2017 Khan Sheikhoun attack to a Sarin attack in April 2013 in the town of Saraqib. Despite it being stated very clearly in the French report that these were two different attacks, Postol had somehow failed to comprehend this, and written a five-page report with the conclusion:

It therefore seems that there are extremely serious discrepancies in multiple intelligence reports that, at a minimum, raise fundamental questions about the veracity of the White House Intelligence Report – and the French Intelligence Report as well. This in turn raises serious questions about how the White House produced an alleged intelligence report that has been shown to have inconsistencies that indicate it could not possibly have been produced and reviewed by the professional US intelligence community.

More than the French report, the thing that was really questioned in this report was whether or not Postol understood how time works.

But, for the moment, let’s ignore the fact Postol’s reports are filled with basic errors, and focus on Hersh. Does anything in Postol’s reports support the claims made by Seymour Hersh in his Welt article? The simple answer is no.

While Postol does seem very interested in fighting what he sees as the “White House narrative,” there’s actually nothing in his report that directly supports Hersh’s specific claims about a Syrian SU-24 dropping a precision munition on a Jihadi command and control center in the north of Khan Sheikhoun. Postol’s work, while rambling and littered with basic errors and misunderstandings, makes no reference to Jihadi command and control centres or precision munitions. In fact, in his first report, he claims Sarin was released from a metal tube filled with Sarin, placed in the crater identified by multiple sources as the release site for the Sarin, and blown up by local rebels. This is certainly not the scenario Hersh describes, which denies that any Sarin was present at the site.

It appears that to Hersh, the primary value of Postol’s reporting is providing another voice contradicting the “White House narrative” which in reality also contradicts the narratives of the OPCW, France, Russia, Syria, and local groups, as well as contradicting serious analysis of the open source evidence.

Hersh also refers to the work of Scott Ritter on the Khan Sheikhoun attack, so can we expect to find anything in his writing that supports Hersh’s version of events? Ritter has written two major pieces on Khan Sheikhoun, Trump’s Sarin Claims Built on ‘Lie’ in the American Conservative before the release of the OPCW FFM report, and Syria’s Alleged Sarin-Gas Attack: Questioning a Flawed Investigation, published after the release of the OPCW FFM report.

Ritter states in the first piece that “In the interests of full disclosure, I had assisted Mr. Hersh in fact-checking certain aspects of his article; I was not a source of any information used in his piece”, and the focus of this piece is comparing the narratives proposed by, as he puts it, “the governments of the United States, Great Britain, France, and supported by the likes of Bellingcat and the White Helmets” and the narrative “put forward by the governments of Russia and Syria, and sustained by the reporting of Seymour Hersh, is that the Syrian air force used conventional bombs to strike a military target, inadvertently releasing a toxic cloud from substances stored at that facility and killing or injuring civilians in Khan Sheikhun.”

It is this last quote that is particular relevant to Hersh, and his referral to Ritter’s work. Claiming the Russian and Syria narrative is “sustained by the reporting of Seymour Hersh” may, on the surface, appear to be correct. The Russian, Syrian, and Hersh narratives all claim that a building was bombed, releasing poisonous gas. However, the actual details of Hersh’s and the governments’ claims are mutually exclusive and contradict one another. The claims from the Russian and Syrian governments published in the aftermath of the attack described a chemical weapons warehouse in the east of town bombed around 11:30am local time. In Hersh’s version of events, a command and control centre in the north of town was bombed at 6:30am local time, thus a different location, time, and target type than the Syrian and Russian governments claimed.

As with Postol’s work, it seems Ritter’s main value to Hersh is another voice claiming the “White House narrative” is untrue, and, as with Postol’s work on Khan Sheikhoun, provides no new evidence that directly supports Hersh’s claims.

What seems clear is that Hersh has no way to defend his reporting. Rather than producing further evidence to support the claims he published in Welt, he is instead looking for anyone who he believes is credible enough to contradict the official “White House narrative” of events, even if, in reality, these sources have poor and mistake-filled reporting, and do not even directly support Hersh’s own claims.