Bahamut, Pursuing a Cyber Espionage Actor in the Middle East

This post was co-authored with Claudio Guarnieri, a security researcher specialized in investigating computer attacks and tracking state-sponsored hacking campaigns. He contributed to this report independently from any affiliation.

Introduction

Beginning in December 2016, unconnected Middle Eastern human rights activists began to receive spearphishing messages in English and Persian that were not related to any previously-known groups. These attempts differed from other tactics seen by us elsewhere, such as those connected to Iran, with better attention paid to the operation of the campaign. Curiously, the two initial targets have little in common with each other aside from human rights activism – although not having worked on overlapping issues or countries. This dissimilarity only grew with the further enumeration of other targets, describing a broad targeting across the Middle East without wholly implicating any particular interest, despite clear political intent.

After extensive work to unpack other potential attacks, we begin to describe an actor that has demonstrated higher than average care to avoid discovery, and shown an ability to learn quickly from past mistakes. Efforts to track the operator describe a group that is broadly interested in a diverse set of Middle Eastern interests, from Iranian women’s rights activists to Turkish government officials, and from Saudi Aramco to a Europe-based human rights organization focused on the region. A significant number of the targets of the group are connected to Qatar’s domestic and international politics, drawing recurring parallels to previous campaigns and suggesting a partial connection to the country. Few state interests would convincingly account why someone would engage in espionage against Egyptian lawyers at the same time as Iranian reformists, leaving open the possibility that the operator is a non-state actor with diverse motivations. Still, the operation’s ambitious attempts against Arab foreign ministers and civil society, and dozens of others, warrants special interest. These incidents also reflect current tensions among Gulf states, undergirding the ubiquitous and central role of cyber espionage in Middle Eastern statecraft.

In absence of personally-identifiable information or even descriptive identifiers within the campaigns, we are labeling this actor “Bahamut,” after Jorge Luis Borges’ monstrous fish afloat in the fathomless Arabian Sea from the Book of Imaginary Beings. Regardless of who is behind the campaign, these incidents provide a window into the broad scale of Middle Eastern cyber espionage and the constant struggles in attribution of attacks, and we attempt for this report to be understandable even for those not as well versed in digital forensics or cyber security.

Credential Harvesting

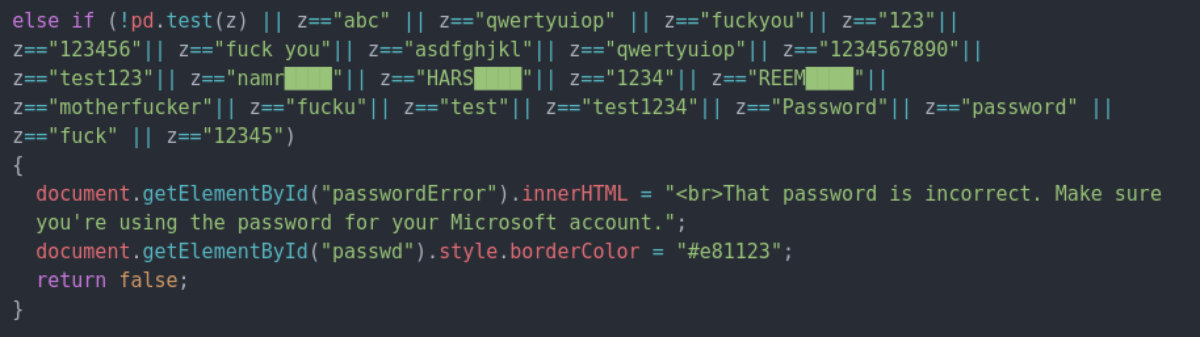

Our direct observation of in-the-wild spearphishing attacks staged by the Bahamut group have been solely attempts to deceive targets into providing account passwords through impersonation of notices from platform providers. The tactics taken in these attempts revolve around credential theft, and while the group is not extremely sophisticated it has sometimes demonstrated considerable ingenuity, flexibility and professionalism. Bahamut was first noticed when it targeted a Middle Eastern human rights activist in the first week of January 2017. Later that month, the same tactics and patterns were seen in attempts against an Iranian women’s activist – an individual commonly targeted by Iranian actors, such as Charming Kitten and the Sima campaign documented in our 2016 Black Hat talk. Recurrent patterns in hostnames, registrations, and phishing scripts provided a strong link between the two incidents, and older attempts were found that directly overlapped with these attacks. Over the course of the following months, several more attempts against the same individuals were observed, intended to steal credentials for iCloud and Gmail accounts.

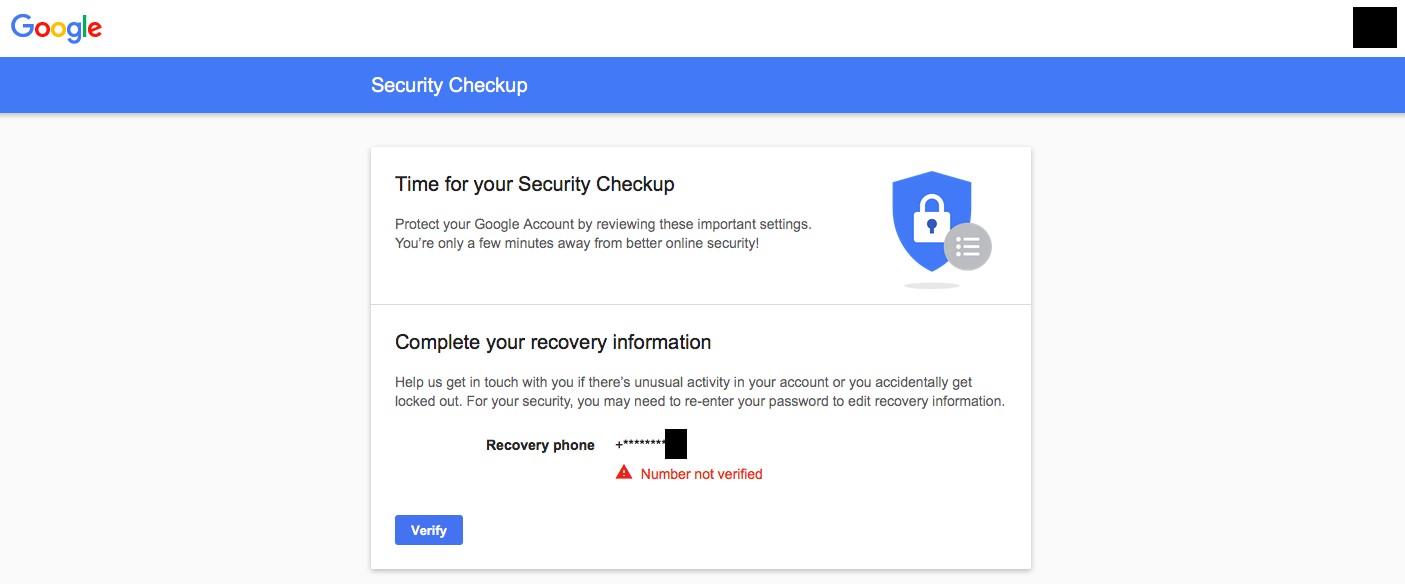

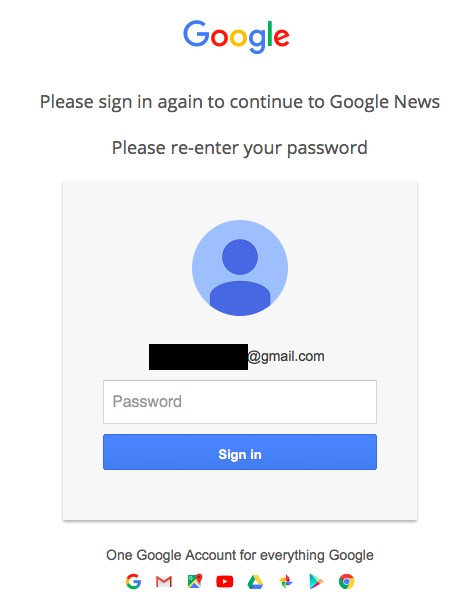

The credential harvesting campaigns that were observed reflect a moderately professional attempt at impersonation of platform providers, certainly better than the average level of care and preparation seen in the everyday cybercrime that most people have become accustomed to. Messages included titles such as “Security info Confirmation” and “Verify your added email,” warning the user to sign in to confirm their account settings or they would lose access. Later attempts posed as a warning to the recipient that the application Truecaller had been granted full access to their account, and that “if you did not rеmоvе this аpp, the аpp rеquеst will be cоnfirmеd” (sic). As is also common, these messages were sent from Gmail accounts registered to appear official (e.g. info.auth.services (at) gmail). To improve credibility, the attackers even displayed a correct but redacted phone number for the account, which we believe they found through the account recovery process of Gmail. Based on crawling the attacker’s infrastructure, other pages hosted on the same site appeared designed to capture the second credential in two-factor authentication or to compromise the account through deceiving the user to engage in Google’s account recovery process.

Bahamut was also observed engaging in reconnaissance and counter-reconnaissance attempts, intended to harvest IP addresses of emails accounts. One attempt impersonated BBC News Alerts, using timely content related to the diplomatic conflict between Qatar and other Gulf states as bait. This message used external images embedded in the email to track where the lure would be opened. Timestamps contained in the URLs of these tracking images indicate that they were uploaded on April 20. The tactic also aligns with the credential theft attempt we describe in the following section, including with respect to timing.

Tracker Image (Unix Timestamp Bold): hxxp://res.cloudinary[.]com/demcz0ffi/image/upload/v1492692894/inx_header_j31vtx.png

Two features stand out within these phishing pages. First, Bahamut is a multi-lingual actor, although an imperfect one. Samples of attempts were observed in English, Arabic and Persian, with two-letter language codes passed as parameters to the phishing site to tailor the page to the victim. Based on adjusting these parameters, there was no indication that other languages – not even regional languages such as Turkish, Hebrew, Kurdish, or Urdu – were supported on the phishing pages, let alone French or other international languages.

Another minor but common improvement were the group’s evasion tactics. Bahamut often replaces Latin characters with similar letters from other alphabets (Unicode homoglyphs) in messages and pages. This means that for example the Latin letter “i” is replaced with the visibly-indistinguishable Cyrillic version “і” in key terms. This technique is generally used to avoid automated scanning by spam filters or other security systems that are looking for suspect words or phrases such as “sign in.”

| Ρlеаse sіgn in аgаin to cоntinuе to Gmаіl | (Greek Rho)l(Cyrlic e)(Cyrillic a)se s(Cyrillic i)gn in (Cyrillic a)g(Cyrillic a)in to c(Cyrillic o)ntinu(Cyrillic e) to Gm(Cyrillic a)(Cyrillic i)l |

Victimology

What makes Bahamut novel is not their techniques but their interests. Across our brief windows of visibility into their activity, there is a consistent set of fundamental interests that suggests political espionage rather than economic motivations. Bahamut is not an ordinary cybercrime campaign. Through directly reported phishing incidents, artifacts harvested from their infrastructure, and other public records, Bahamut appears to be a sustained campaign focused on diverse political, economic, and social sectors in the Middle East.

By our observation, the spearphishing attempts appear to be narrowly targeted against a limited number of individuals (perhaps in the lower ‘tens’ per month) rather than broad scale. In one instance, in late April 2017, Bahamut appears to have impersonated a Google News alert for an article about Middle Eastern government support for Donald Trump as a lure targeting Anwar Gargash, the U.A.E. Minister of State for Foreign Affairs (screenshot inline from an attempt against Gargash that we observed, which also aligns with our BBC notice). At the same time with the same infrastructure, the false notice about the application Truecaller was used to target a relative of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, a Saudi college student, two Iranian dissidents, and the head of an Emirati think tank.

Operational security failures on the part of the attackers enabled a brief look into their activities. The phishing site in several Bahamut attempts included a profile picture of the target to increase the appearance of legitimacy. These images had predictable and short filenames, often the target’s initials (hypothetically, ‘ag.jpg’ for Anwar Gargash). As a result, we could enumerate potential targets through making requests for combinations of letters. This is a time-consuming and aggressive process: for a three-character maximum (from ‘a.jpg’ up to ‘zzz.jpg’) the search would entail 17,576 requests. These images were also organized in different folders – an organizational structure that could either reflect different campaigns or internal processes (with folder names of ‘ky’, ‘ct’, ‘dy’, and ‘er’). To search all four folders further increased the amount of requests, involving 70,304 requests for each site. While not a stealthy search, when a similar opportunity arose in our investigation for Amnesty’s “Operation Kingphish” report, it was a successful and worthwhile one.

We could be reasonably confident that those images that were return in this brute force search were individuals targeted by Bahamut. The profile pictures also included metadata indicating that the images were copied from Google profiles, further suggesting prior reconnaissance. Multiple individuals identified in this manner later confirmed receiving spearphishing messages in recent months, none were surprised about the apparently political nature of the campaign.

This search yielded 59 images on three domains, with a little more than half being unique pictures. Where the individuals targeted could be identified, the themes reinforce the hypothesis that Bahamut is focused on Middle Eastern political and economic institutions. Moreover, those limited number of non-Middle Eastern targets – Swiss and British nationals – have prolonged involvements in the region as journalists, diplomats, or human rights advocates. Of those clearly identifiable, the targets have been primary located in Egypt, Iran, Palestine, Turkey, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates, including:

Arab Middle East

- a company that provides financial services that caters to high-net worth clients with an emphasis on “confidentiality”;

- Egypt-focused media and foreign press, including individuals previously imprisoned in the country;

- multiple Middle Eastern human rights NGOs and local activists;

- a diplomat in the Emirati Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Emirati Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, and the head of an Emirati foreign policy think tank;

- a prominent Sufi Islamic scholar; and,

- the Union of Arab Banks.

Turkey

- a Delegate of Turkey to UNESCO; and,

- the Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Iran

- a relative of the President of Iran;

- a women’s rights activist and a prominent female journalist in the diaspora; and,

- a reformist politician who is an advisor to the former President Khatami.

Still more references in Virustotal and other databases implicate the actor in additional attempts against Gulf institutions, including the Prime Minister’s Court of Bahrain, the Saudi Minister of Energy, and a former member of the Saudi Arabian National Security Council. It is also notable that for a Middle East focused actor, none of the targets of the Bahamut operation appeared to be connected to Israel, but we do not believe the group to be Israeli.

Infrastructure

Bahamut has taken clear precautions in order to avoid scrutiny. Often researchers unravel the vast network of infrastructure used in attacks through following the connections created by the reuse of email addresses in domain name registrations and site hosting. Bahamut’s vigilance cuts the trail short quickly.

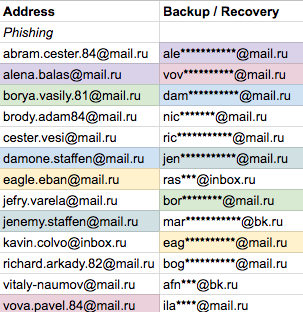

A consistent theme in the registration of Bahamut domain names is the use of private registration services and throw away accounts from the Mail.Ru Group. The fictitious email addresses are fairly consistent – an Anglo-European name sometimes followed by a number at mail.ru. Each account is used for the registration of only one domain. These addresses also appear in the other records for the domain (specifically, the Start of Authority record in DNS). Only on rare occasions do the attackers slip up and mismatch the accounts used between both records. A subtle web is weaved based on the accounts being connected through their reuse as recovery addresses when they create new accounts.

Similarly, while multiple phishing sites are maintained by Bahamut in parallel, the sites are hosted on their own dedicated servers. While domains may be reused across time, the attackers use different subdomains for different campaigns. Importantly, they are quick to take down sites that appear to have been noticed. These shutdowns also provide fingerprint of Bahamut, albeit non-exclusive to the group, which commonly entail redirection (HTTP 302 code) to the “www.accessdenied.com” site.

Attack subdomains for Bahamut, including a subdomain believed to target the Prime Minister’s Court of Bahrain (domain: my-validation[.]info):

valid.appid.support.validate-maillogon.service.authuser.continue.frontend.reason.redirect.file-manager.version-9.1.101.view-settings.svjjykd5v2vum3fbsxlgmxfmr3pjdklh.access-https.my-validation[.]info

vvebrnail.prnc.gov.bh.362393h11idk.930012hfifd994.acccess.authdll.my-validation[.]info

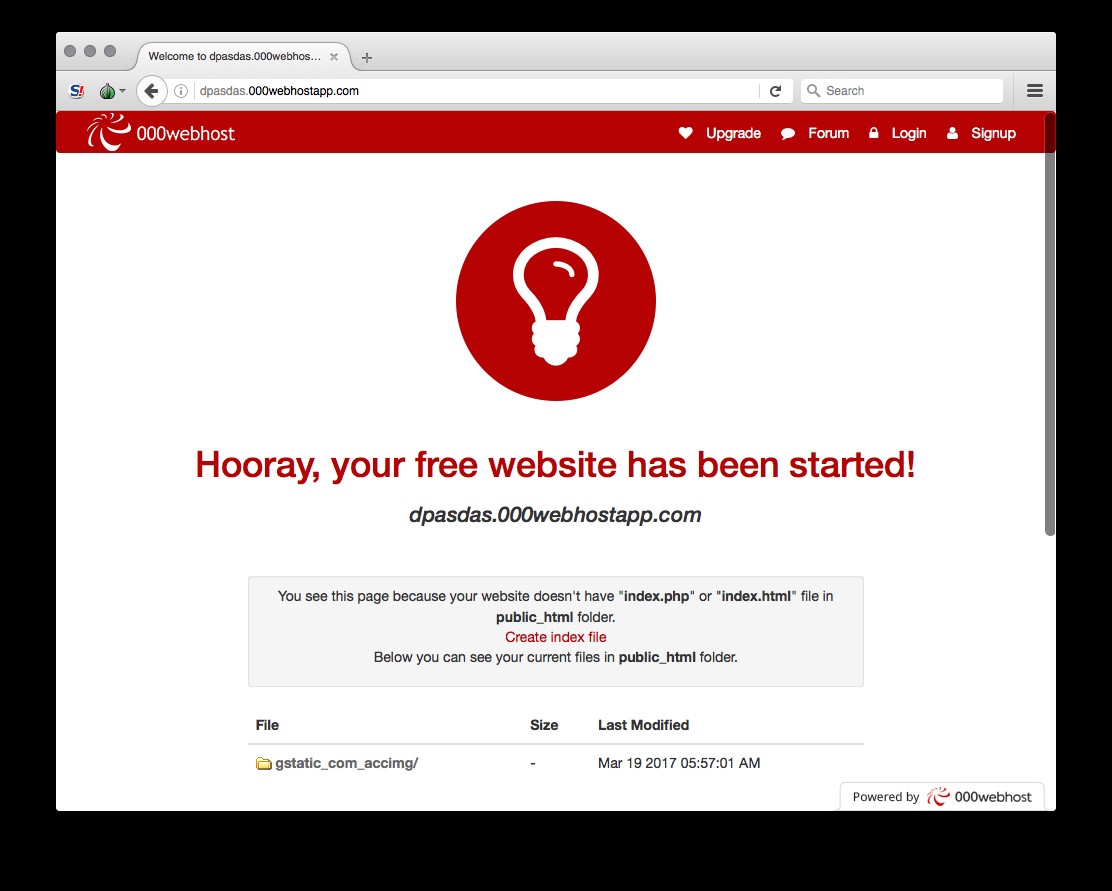

Our investigation has also shown a clear learning process. Whereas previous sites would stay active for days after an attempt, in recent incidents it was deleted within minutes (perhaps automatically) and the subdomain is taken offline within the day. In doing so, Bahamut narrowed the window for forensic investigation, quite effectively. After the crawling of images and victim information was noticed, Bahamut took further steps to hide their infrastructure – using free hosting services as a redirection mechanisms and for hosting images used in phishing emails.

Overlapping Infrastructure

While Bahamut took precautions to avoid linkability, it has concentrated on a limited number of networks. Specifically, it has a tendency to use hosting companies known to be slow to respond to abuse. These habits build fingerprints. Combining their preference for certain networks with their patterns in fictitious registration addresses, we can began build searchable indicators to identify other domains associated with the same group – albeit weak indicators.

In order to identify more of the attacker’s infrastructure, we aggregated all the domain names we could find that have been pointed to the networks known to be used by Bahamut from various sources (e.g. passive DNS and DomainTools). We then queried those domains (for the SOA “rname” record) and flagged those with a Mail.Ru Group address. Mistakes on their part also led to more suspicious mail addresses to search on. The resulting group was surprisingly small given the open-ended search (included in the Indicators of Compromise section below). No resulting domain appeared to be a legitimate site, or even directed toward more standard cybercrime. Most appeared to be credential harvesting sites similar to our original set, with some confirmed to be malicious and relevant based on URLs appearing in Virustotal.

Four domains stand out as different from credential theft and are worth additional discussion.

| my-validation[.]info | 91.235.143.214 | 91.235.143.199 | alfajrtaqni[.]org | 86400 IN SOA ns1.alfajrtaqni.org. wendy.walker.bk.ru. 2016051403 3600 7200 1209600 86400 |

One of the domains within this set is a mirror of the al Qaeda associated Al Fajr Media Center Technical Committee. al-Fajr Media Center is the developer of the “Security of the Mujahid” (Amn Almujahid) encryption application, and the site in question hosts copies of the application. Despite the creation of the domain on March 2016, it appears to be an out of date mirror of the al-Fajr Media Center captured in March 2015, potentially from another mirror (alfajrtaqni[.]ws). While the suspicious al-Fajr Media Center hosts an older version of the organization’s Android and Windows applications, with newer versions posted to the real site after the snapshot was taken, those files appear to be same as the original (same checksums). There is little indication as to how the site was used.

The remaining three are equally interesting:

| Domain | IP | DNS SOA Record (Includes Mail.Ru Group Email) |

| 16linesquran[.]info. | 178.17.171.140 | 86400 IN SOA ns1.16linesquran.info. m.cutov.mail.ru. 2016041500 3600 7200 1209600 86400 |

| khuaitranslator[.]com. | 178.17.171.39 | 86400 IN SOA ns1.khuaitranslator.com. andy.mingle.mail.ru. 2017040514 3600 7200 1209600 86400 |

| timesofarab[.]com | 91.235.143.246 | 86400 IN SOA ns1.timesofarab.com. randall.kaine.mail.ru. 2017010303 3600 7200 1209600 86400 |

Android Malware

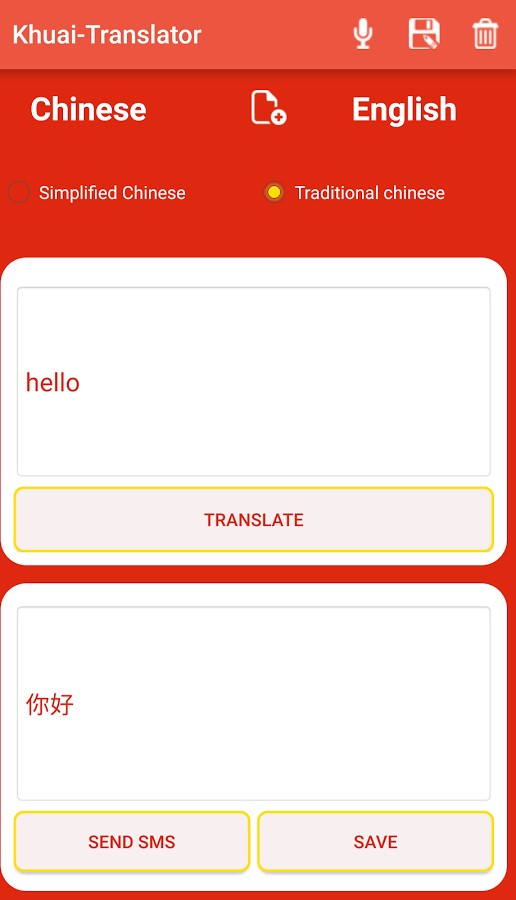

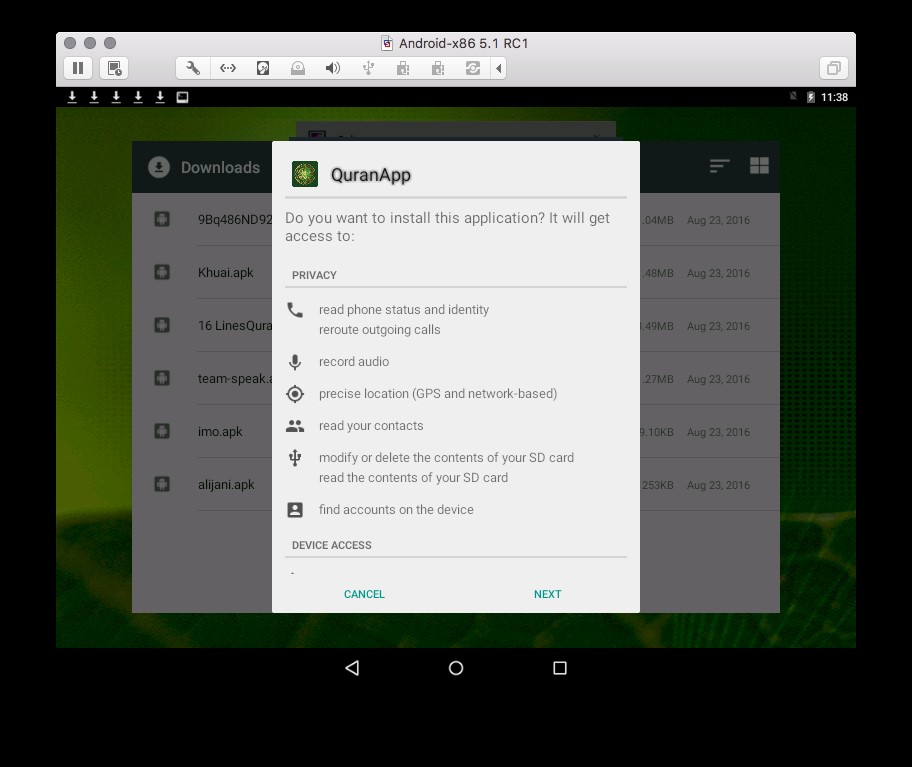

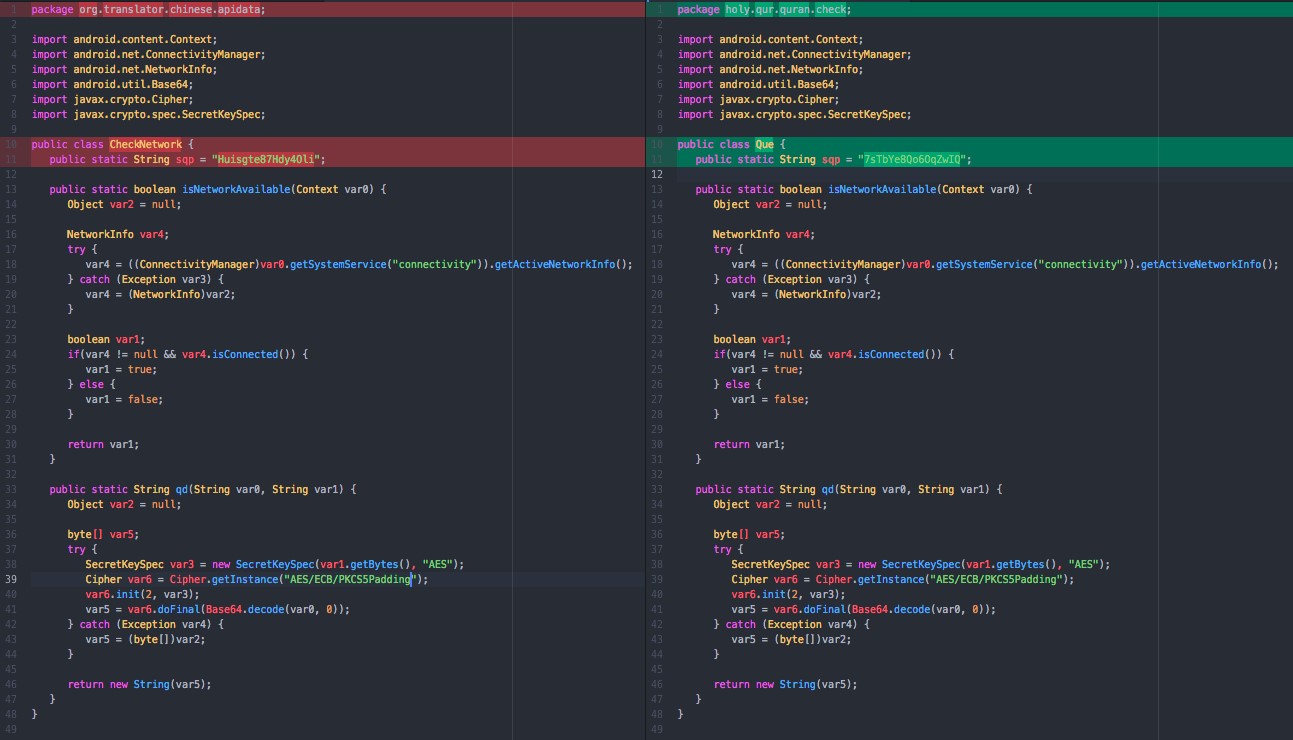

Two of the suspicious sites are connected with Android applications, which are custom malware agents that have not been widely-promoted (again, unlike most cybercrime). The “16 Lines” and “Khuai Translator” applications have small installation bases (respectively, “50-100” and “1-5” from Play Store statistics). The 16 Lines app, last release in March 2016, is a fully functional Urdu-language Quran application. Khuai Translator is a Chinese-English translator that relies on Yandex’s translation service (despite also including code for Microsoft’s service) and is a little more than four months old. Unsurprisingly, Khuai Translator appears to have appropriated its name from a Firefox extension, and 16 Lines from a Quran archive. In neither case is it clear who the intended audience of the application is, and there is little record of their domains being pushed to targets.

| 16 Lines Quran | https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=holy.qur.quran | szymon.tchorzewski88@gmail.com |

| Khuai Translator | https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.translator.chinese | caren.hee789@gmail.com |

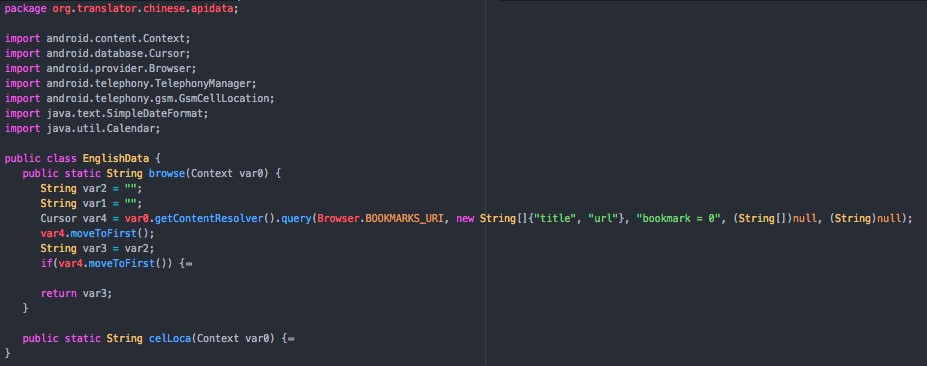

As would be expected, both applications are designed to exfiltrate private information from the mobile device and monitor the activities of the target, reporting back to the attacker:

- SMS messages and phone call logs;

- contact information from the address book;

- browser history and bookmarks;

- phone hardware identifiers; and,

- precise location and network information.

Both also advertise recording functions in the actual application, such as recording Quranic recitations or words for translation. This may be offered in order to provide a veneer of legitimacy to their large set of required permissions.

The malware is also of low quality – in version 1.1 of Khuai Translator, the URLs to report back to the attacker contain typos (e.g. “htpp://”) that would lead to them being non-functional. This was resolved in a subsequent update, but other typos are present in both applications across web properties, internal functions, and application dialogues, suggesting that quality was not a priority for the attackers.

While the two applications are not exactly the same malware, both appear to have the same core design and tactics, such as hiding the malicious functions within classes that appear related to the legitimate application. In both applications, the malware strangely reports back to a different web address for each type of information with the full URL repeatedly defined; this works fine, but is not something a mature programmer would do. These URLs are individually scattered across the application and encrypted to reduce detection (AES-128-ECB and encoded within latin1 character set). Both samples appear to share the same code for voice recording, network transmission, and encryption of URLs. These commonalities, down to similarly patterned contact addresses on the Play Store, strongly suggest that they have the same maintainers despite the use of pseudonyms and minor differences.

Given the natural differences in audiences between the Android malware and the credential harvesting (China and Pakistan versus the Middle East), it is difficult to be fully confident of the link between both operations. Nothing within the applications directly connects both campaigns, despite other vague similarities. For example, the beacon endpoints of both applications are loosely reminiscent of those of the Bahamut spearphishing campaigns, with short file names, use of the PHP scripting language, and located within randomly-named folders:

- http://www.16linesquran[.]info/dhReqIopT/QzXrvTHG/ct.php

- http://www.khuaitranslator[.]com/TQaxcTr/spPlVl/WordTranslate.php

As of the time of publication, the site associated with 16 Lines Quran was down, returning the same 403 Forbidden message familiar on Bahamut sites. The Khuai Translator’s site and the malware endpoints remain operational.

Times of Arab

Last within the search results is the “Times of Arab” (timesofarab[.]com), on face value the only legitimate appearing site. The Times of Arab is particularly relevant to the Bahamut campaign as it is focused exclusively on the Gulf region. Those behind the site have been consistently active for at least five months. As with the al-Fajr Media Center, its end intent is unclear as no malicious activity has been observed. However, the content and description of the site warrants scrutiny. For example, the About page for the Times of Arab is notable for its overall generic mission and claim of threats against staff (repetition and quotes in original).

To bring substantial news to the surface, which is otherwise underreported by the global media. Our journalists ensure the stories that reach you are impartial and unaffected from any sort of vested interest. We want to reshape the world media by strengthening our bond with the readers, a bond formed with trust and truth. The defined goals are the reason why Times of Arab audience is growing rapidly – audience that appreciates our work. Responsibilities shared by our employees are strenuous, but they are needed in order to report news that is free from perception of any country, state, organization or individual. Although Times of Arab is centered in the Middle-East, our revelations also encompass incisive range of global issues. Times of Arab journalists keep a low profile and wear masks of anonymity due to threats they have recently received from different directions. “Times of Arab journalists keep a low profile and wear masks of anonymity due to threats they have recently received from different directions.”

The premise of threats against the Times of Arab is surprising given the content. The articles posted to the site are uniformly positive stories about Gulf regimes copied from elsewhere, including from regional state media organizations.

The content is both targeted and irregular in quality. The Times of Arab often posts nonsensical articles with mismatched titles, strange combination of images, and misspells country names within the filenames of images (e.g. “soudi,” “saoudi,” “kuaiti,” and “behrain”). For example, an ominous image with the phrase “Arab Spring” – referring to the 2011 uprisings – headlines one article where the content covers a seasonal basketball game that was copied from an Arab, Alabama newspaper (hence, ‘Arab spring game’). While there are occasional technology stories, the majority of the articles focus on regional labor rights and social issues with titles such as “Nepal leaders praise Qatar’s treatment of expat labour” and “[FIFA chief] Infantino praises progress on Qatar 2022 worker conditions.” This focus recalls the themes in targeting in the Operation Kingphish campaign.

The Times of Arab is active across social media, with its uploaded YouTube videos being copied content from AP, Al Jazeera, and other personal YouTube videos – again primarily about Qatar and the Gulf region. The Twitter account of the Times of Arab follows several human rights organizations, such ARTICLE 19, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, including their regional accounts, as well as Qatar and Emirati related accounts – also reminiscent of Operation Kingphish.

Attribution and Origin

The measures taken by the attackers to conceal their identity have constrained our ability to make definitive assertions about who is behind the Bahamut campaign. As noted previously, the consistent use of fictitious personas in registration and maintenance of infrastructure leaves a short trail. The scripts and sites themselves do not have obvious hints as to their origins. Extending out the potential activity to include malware posing as a Chinese-English translator clouds the picture further.

On two occasions, compromised accounts provided IP addresses connected to the attackers. In the first case, initially, the attacker accessed a breached account using a feature that allows Mail.Ru accounts to access Gmail accounts (if they have the proper credentials). This approach allowed the attacker to conceal their original address, to bypass Google’s monitoring of suspicious logins, and to maintain persistent access. However, later they attempted to access the accounts through logging in directly, doing so through two networks in Europe – at least one that was an OpenVPN server (185.113.128[.]207 and 185.161.208[.]37). These addresses provide little direct insight into where the attacker is located, but did bolster their operational security credentials.

In a second case, an account was breached in early morning hours Gulf time through an ADSL connection provided by Emirates Telecommunications Corporation in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (83.110.89[.]246). However, this traffic could be originating from a compromised machine – a possibility supported by the amount of exposed services found in a portscan of the address. The overlap would be especially surprising given that this occurred within the context of attempts against the Emirati Foreign Minister.

Bahamut appears on face value to have common traits with Operation Kingphish, but operates as though it were a generation ahead in terms of professionalism and ambition. The phishing sites found in the campaign also recalls some of the design choices made with the Operation Kingphish attempts against Qatar-focused labor rights activists. For example the ropelastic[.]com phishing site from Operation Kingphish used the same hosting providers seen in Bahamut, had a similar overreliance on the tinyurl URL shortener, and was registered with a “stuart.boarden@mail[.]ru” address (that also used another Mail.Ru account as backup, “mik*********@mail.ru”). This extends to the variable names with the source code of phishing pages and other infrastructure choices of the attackers. Still other artifacts on the spearphish pages are similar and reflect a common thought process, but Bahamut is always an improvement on Operation Kingphish.

Operation Kingphish

IP: 178.17.171[.]25 (AS43289, I.C.S. Trabia-Network S.R.L., Moldova)

Phishing URL: rqeuset.hanguot.g-puls.viwe.accnnout-loookout.auditi.devisionial-checlkout.inistructiion-mutuael.halftoine.appliacctiorn-gurad-way.leigacy-fs.termp-forn.provider-saefe.alvie-valuse.token-centeir.recollect.label.ping2port[.]info/?ml=[REDACTED]=&n@e=[REDACTED]&P4t=[REDACTED]&Re3d=aHR0cDovL3Rpbnl1cmwuY29tL2g5d3h3cDg=&pa=2&gp=1

Profile Image: ping2port[.]info/pc/dl/[REDACTED].jpg

Bahamut

IP: 178.17.171[.]145 (AS43289, I.C.S. Trabia-Network S.R.L., Moldova)

Phishing URL: gdrive.mydocument.validate.googlsupport.servicelogon.continue.owa.frontend.redirect.reason.file-manager.version-9.912.settings.sxoxakuxsgtis3vgslrrs0x6zjfwwlnjbsdfsm.access-https.authprofile[.]info/m/?t0R1I2A=[REDACTED]=&nJm=[REDACTED]==&pc=&ReJd5S=[REDACTED]&gn=1&hr=[REDACTED]==&lan=en&rc=&VeRcEm=&VeRcPh=

Profile Image: authprofile[.]info/iMHgT/dy/[REDACTED].jpg

| Comparison of HTML of Kingphish and Bahamut Google Phishing Pages | |

| <input type=”hidden” id=”qst” name=”qst” value=”[Redacted]”>

<input type=”hidden” id=”ua” name=”ua” value=”Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; rv:45.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/45.0″> <input type=”hidden” id=”url” name=”url” value=”http://rqeuset.hanguot.g-puls.viwe.accnnout-loookout.auditi.devisionial-checlkout.inistructiion-mutuael.halftoine.appliacctiorn-gurad-way.leigacy-fs.termp-forn.provider-saefe.alvie-valuse.token-centeir.recollect.label.ping2port.info/[Redacted]”> <input type=”hidden” id=”lan” name=”lan” value=”en-US,en;q=0.5″> <input type=”hidden” name=”yt” value=””> <input type=”hidden” name=”gd” value=””> <input type=”hidden” name=”gp” value=”1″> <input type=”hidden” name=”gpl” value=””> <input type=”hidden” name=”gn” value=””> <input type=”hidden” name=”pa” value=”2″> <input type=”hidden” name=”2St” value=””> <input type=”hidden” name=”VerRecPn” value=””> <input type=”hidden” id=”Re3d” name=”Re3d” value=”[Redacted]”> <input type=”hidden” id=”pm” name=”pm” value=””> <input type=”hidden” id=”tst” name=”tst” value=””> |

<input type=”hidden” name=”redirect” id=”redirect” value=””/>

<!– http-ref –> <input type=”hidden” name=”url” id=”url” value=”http://validateuserid.servicelogon.authsupport.owa.frontend.continue.reason.redirect.file-manager.version-9.10.112.view-settings.vmpgu1qxrxlwbk5qum14vlltnunvrlpzvwxkvwbxm1.access-https.myprofileprivacy.com/m/index.php?[Redacted]”> <input type=”hidden” name=”ua” id=”ua” value=”Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; rv:45.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/45.0″/> <input type=”hidden” name=”blang” id=”blang” value=”en-US,en;q=0.5″/> <input type=”hidden” name=”HTTP_ACCEPT” id=”HTTP_ACCEPT” value=”text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8″/> <input type=”hidden” name=”pgTitle” id=”pgTitle” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”dwn” id=”dwn” value=””/> (…) <input type=”hidden” name=”yt” id=”yt” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”st” id=”yt” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”bc” id=”yt” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”VeRcEm” id=”VeRcEm” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”VeRcPh” id=”VeRcPh” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”2Sp” id=”2Step” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”gp” id=”gp” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”gd” id=”gd” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”gpl” id=”gpl” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”rcvry-em” id=”recovery” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”rcvry-ph” id=”recovery” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”rjc” id=”recovery” value=”1″/> <input type=”hidden” name=”code” id=”recovery” value=””/> <input type=”hidden” name=”nJm” id=”recovery” value=”[Redacted]”/> <input type=”hidden” name=”redirect” id=”redirect” value=””/> |

Unlike Operation Kingphish, which from our observation was mostly focused on internal Qatari politics, Bahamut is responsive to the internal affairs of several Middle Eastern countries – targeting individuals that are solely focused on domestic politics of different countries at sensitive times, such as Iranians in the lead up to the Iranian Presidential election in May 2017. As a result, there is not yet a definitive link between Kingphish and Bahamut despite the overlap in time.

Despite its focus on Iranian targets, Bahamut does not appear to be Iranian, or well prepared to effectively target Persian speakers. In the one Persian-language spearphishing email observed, the content was poorly-written with the grammatical mistakes that would be expected of Google Translate. The attackers also incorrectly use “pe” to identify whether the phishing page should be Persian – we would expect that a Persian-language speaker would be aware that the correct designation is “fa.”

Relatedly, the English used in the messages reflected the grammatical mistakes of a non-native speaker (rather a translation) combined with a lack of concern or awareness about professionalism. The single Arabic-language page that we were able to find had similar lack of professionalism – using the Arabic for “verify” rather than the “sign in” that is actually used by Google. Unlike Persian this was seemingly a mistake of professionalism rather than capability and did not necessarily indicate the use of a translation service.

We would be remiss not to address the frequent use of Russian services: this does not stand out beyond what we might expect of someone attempting to avoid scrutiny, such as using a provider that does not require phone numbers or comply with U.S. law. Many non-Russian groups use services such as Yandex and Mail.Ru, and so there is no indication of Bahamut being of Russian-origin.

In the end, our selection of the name “Bahamut” is motivated by the strange behavior of the group, which seems to sprawl across different countries and contexts. If the malware agents, Kingphish, and the observed spearphishing attempts are all in fact related, then Bahamut’s interest exceed our expectations for the espionage activities a single Middle Eastern country. While Gulf countries have global interests, the targeting of obscure Iranian reformist figures, let alone the creation of Urdu and Chinese language malware applications, stretches the boundaries of imagination. Taken in the context of the overlapping domains, the diversity suggests that Bahamut is not necessarily a state actor, and instead could be a more independent entity seeking financial remuneration from more than one client.

Conclusion

Whoever is behind the spearphishing and malware documented, the Bahamut campaign is descriptive of how unique the Middle East is in terms of cyber espionage and other cyber operations. The diverse set of political and economic interests that makes the region so contentious draws in attention from many actors for different motivations. These incidents also bear witness to a region in technological transition. As is well documented by now, international powers are actively engaged in cyber espionage against diverse targets in the Middle East, while several regional states have begun to pursue their own interests. These offensive and defensive capabilities are not uniform, and the purchase of arms from abroad has not been shown to include tools for conducting cyber options (aside from surveillance platforms). Bahamut is therefore notable as a vision of the future where modern communications has lowered barriers for smaller countries to conduct effective surveillance on domestic dissidents and to extend themselves beyond their borders.

Indicators of Compromise

Staging

dpasdas.000webhostapp[.]com

mailgooqlecominboxasm9003nmjknsidnpopjdasdkopm.000webhostapp[.]com

Observed Credential Harvesting

authprofile[.]info

authuser[.]info

myprofileprivacy[.]com

myprofileview[.]info

myvalidation[.]info

session-id[.]com

ver-icloud[.]com

my-validation[.]info

profilesupport[.]info

Overlapping Infrastructure

16linesquran[.]info

alfajrtaqni[.]org

khuaitranslator[.]com

mail-sllogin[.]com

timesofarab[.]com

ernail-ver[.]com

rnail[.]info

session-icloud[.]com

cert-icloud[.]com

myinfosettings[.]com

update-mailservice[.]com

my-auth[.]info

infocheckup[.]com

managemysettings[.]com

manage-mysettings[.]com

web2chost[.]com

com-settings-ppsecure[.]com

golge[.]cc

mainlogin[.]co

icloud-auth[.]com

acc-dot[.]com

Overlapping Android Malware

73f2c81473720629be32695800b7ad83494f2084 Khuai Translator v1.2

2f239a96987284a4883014cf1dad39c16f8fc7ad Khuai Translator v1.1

60191fa19fb1184535608d7640a11320e59b0ab2 16 Lines v1.1

Khaui Translator encryption key: Huisgte87Hdy4Oli

16 Lines encryption key: 7sTbYe8Qo6OqZwIQ