Eyes on Aleppo: Visual Evidence Analysis of Human Rights Violations Committed in Aleppo [July - Dec 2016]

On 28 March 2017 the Syrian Archive published a new report, Eyes on Aleppo: Visual evidence analysis of human rights violations committed in Aleppo [July – Dec 2016]. The report describes and investigates a new visual evidence dataset of 1748 videos of human rights violations in Aleppo city and the surrounding suburbs during the period of July – December 2016. A complete methodology of the report is available on the Syrian Archive website.

The following visual evidence dataset complements and supports recent efforts by different groups which have been assisted by the Syrian Archive to report human right violations in Aleppo between July and December 2016. Those efforts include:

- UN Human Rights Council (Feb. 2017): “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic”

- Atlantic Council (Feb. 2017): “Breaking Aleppo”

- Human Rights Watch (Feb. 2017): “Coordinated Chemical Attacks on Aleppo”

- Various investigations by (July 2016 – March 2017 ) Bellingcat.

While attacks and violations have been committed by all parties, including the International coalition and Turkish forces, visual evidence shows that the Syrian and Russian forces were responsible for the largest number of human rights violations in Aleppo city and its suburbs during the analyzed period. These violations include:

- Attacks against hospitals, medical units, ambulances, schools, water stations, markets, mosques, bakeries and residential areas;

- The use of illegal weapons such as incendiary weapons and chemical weapons against civilians;

- Unlawful attacks on residential areas using cluster munitions;

- Attacks against humanitarian aid workers and citizen journalists;

- Attacks against women and children;

- Forced displacement of civilians.

Below is a summary of report findings disaggregated by type of violations identified, specific munitions identified, and location of where videos were filmed.

Types of violations identified

An analysis of videos of violations disaggregated by the following types of violations:

- Arbitrary and forced displacement;

- Sieges and economic, social and cultural rights;

- Specially protected persons and objects;

- Unlawful attacks;

- Use of illegal weapons;

- Violation of children’s rights, and;

- Other types of violations

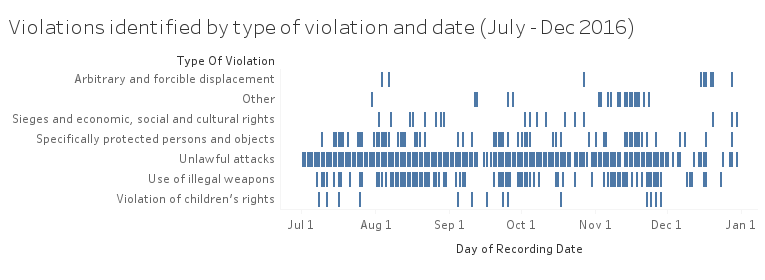

A summary table of violations by type and date is provided below.

Arbitrary and forcible displacement were identified in eighteen (18) videos. A March 2017 report on the situation in Aleppo by the international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic found that “as warring parties agreed to the evacuation of eastern Aleppo for strategic reasons – and not for the security of civilians or imperative military necessity, which permit the displacement of thousands – the evacuation agreement amounts to the war crime of forced displacement.”

Sieges and economic, social, and cultural rights were identified in nineteen (19) videos. For the purposes of the report, the Syrian Archive defined sieges and violations of economic, social and cultural rights as incidents in which civilians are suffering from lack of basic necessary resources tied to the siege (e.g. difficulty in obtaining adequate food or water, or suffering as a result of lack of medical infrastructure). It also refers to incidents in which civilians suffered as a result of evacuation. Finally, it refers to incidents in which heritage and cultural sites were damaged or destroyed. It is recognised that many of these incidents also fall under the category specially protected persons and objects or other violation categories; however, in the report it refers only to those in which attacks are not directly filmed. Incidents in which attacks were directly documented have been categorised under alternate violation categories.

Due to siege of Aleppo city between July to December 2016, it was recognised that the figure representing violations may severely under represent the total number of siege related violations, as most videos of violations fall under the siege violation category. Here, these nineteen videos describe when the Syrian Archive was unable to attribute other-non-siege related violations.

Violations of specifically protected persons and objects were able to be identified in one hundred forty-seven (147) videos. The Syrian Archive used the customary international humanitarian law (IHL) definition of specially protected persons and objects, Rule 25-30 of which defines as hospitals, ambulances, and medical personnel. While these may be the object of attack when used for military purposes, prior warning is needed.

The display of an emblem to signify a location’s protected status is not required in conflicts where hospitals are deliberately targeted, and the treatment of wounded fighters does not render a hospital a valid military objective. Rule 38 ‘Attacks Against Cultural Property’ of customary IHL states that special care must be taken in military operations to avoid damage to buildings dedicated to religion, art, science, education or charitable purposes and historical monuments unless they are military objectives, and also that property of great importance to the cultural heritage of must not be the object of attack unless imperatively required by military necessity. Rule 27, 31, and 32 of IHL states that religious personnel exclusively assigned to religious duties must be respected and protected in all circumstances, though they lost their protection if they commit, outside of their humanitarian function, acts harmful to the enemy.

Unlawful attacks make up the bulk of violations identified in video footage, comprising 1,260 videos. IHL Rule 12 considers an attack unlawful if it “is not directed at a specific military objective, employs a method or means of combat which cannot be directed at specific military objectives, or employs a method or means of combat where the effects of which cannot be limited as required by IHL and as a result strike military objectives and civilians or civilian objects without distinction.”

Violations of the use of illegal weapons have been identified in two hundred and forty (240) videos. The March 2017 international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic states that Syria has ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention in 2013, following findings by the Organisation for the prohibition of Chemical Weapons that government forces had used chlorine bombs in an earlier phase in the conflict. IHL Rule 74 states that the use of chemical munitions are prohibited in both international and non-international conflicts. Rules 11, 12, and 71 of International Humanitarian Law state that the use of cluster weapons in densely-populated areas which are by their nature indiscriminate and whose effects cannot be limited is also prohibited. Further, IHL Rule 85 states that the anti-personnel use of incendiary weapons is prohibited unless it is not feasible to use a less harmful weapon.

Violations of children’s rights were identified in twenty-one (21) videos. The Syrian Archive categorised violations of children’s rights as videos depicting children injured, killed, or being treated in a hospital as a direct result of an attack. The total number of videos featuring violations of children’s rights is likely much higher, as, for the purpose of the report, only one category was applied and many may fall under the category of unlawful attacks.

Lastly, “Other” refers to videos that were filmed from far away and where the Syrian Archive was unable to determine whether a residential area was targeted. It refers also to videos where no voice was in the video mentioning, for example, the potential type of munition or perpetrator. Other also refers to videos showing attacks on a frontline in a residential area or attacks on legitimate military targets.

Frequency of violations

A Gantt chart of the frequency of violations in Aleppo shows that violations of all types occurred regularly and throughout the July – December 2016 period.

This analysis demonstrates that arbitrary and forcible displacement are more common towards the end of the battle for Aleppo city. Violations of specifically protected persons and objects occur regularly and throughout that battle. Likewise, unlawful attacks and the use of illegal weapons occurred regularly throughout the July – December 2016 period, and in some cases almost daily.

Intensity of violations

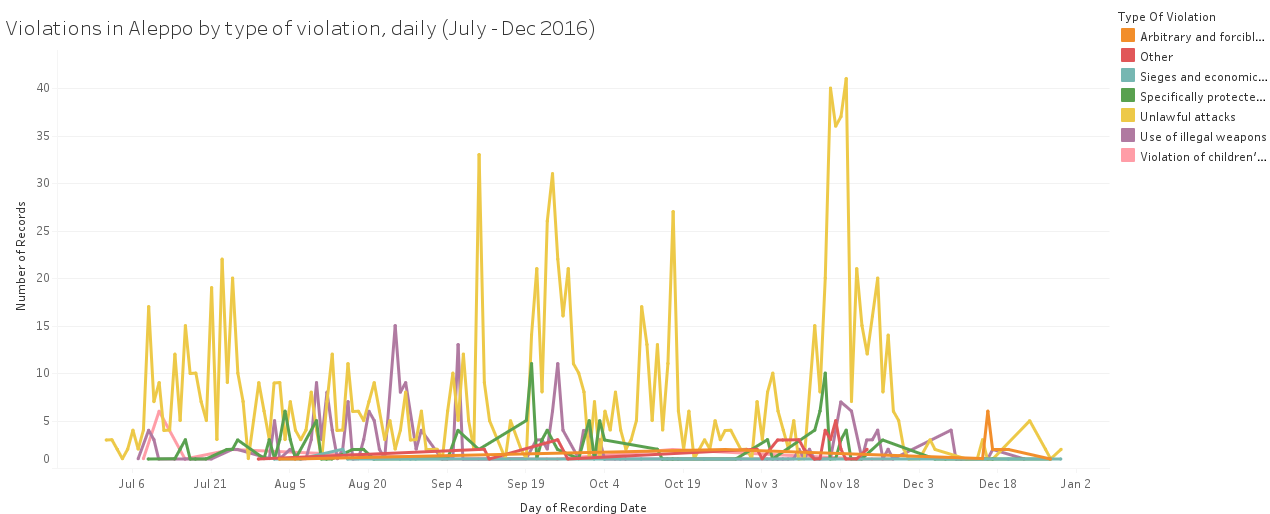

A time series analysis demonstrates the intensity at which videos of violations were uploaded in the July – December 2016 period.

Like the Gantt analysis, the time series analysis demonstrates consistent and repeated evidence of violations in Aleppo during the July – December 2016 period. Unlawful attacks, the majority of which being attacks against civilians and residential areas, make up the majority of violations documented.

Illegal weapons were used and attacks against specially protected persons were witnessed frequently and consistently throughout the July – December 2016 period, coinciding with peaks in the number of videos documenting unlawful attacks. In some cases, illegal weapons were identified in the same incidents deemed unlawful, however videos are categorised only accordingly to which violations are observed within each video.

Arbitrary and forcible detention videos occur throughout, but peak in December as many fleeing Aleppo were unlawfully detained.

Specific munitions identified

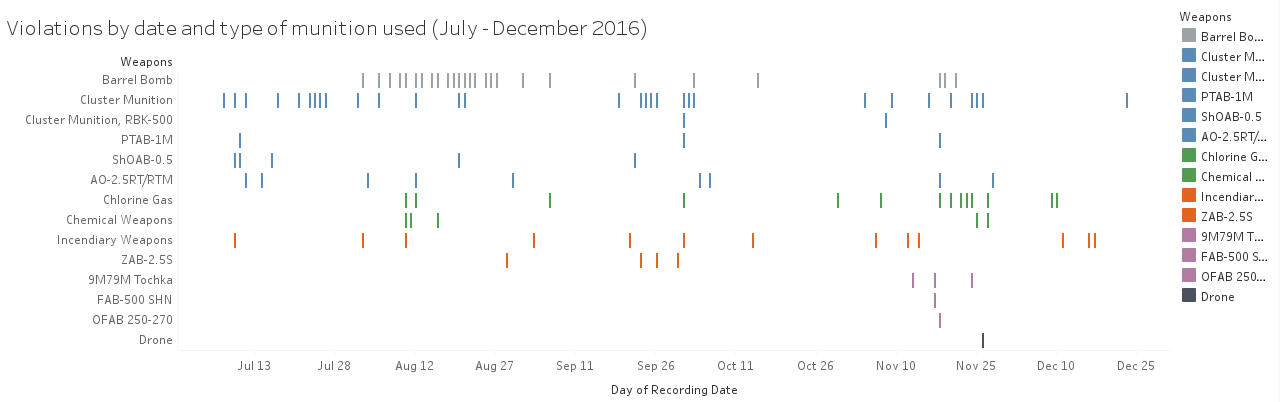

Through assistance from Amnesty International’s Digital Verification Corp, Bellingcat investigators, and others, the Syrian Archive was able to identify specific munitions found in visual evidence. To identify the frequency of use of specific munition types in violations, an analysis of the violations database, disaggregated by type of munitions used was also conducted.

In many cases, specific munitions or submunitions were identified in video footage. In some cases, the Syrian Archive was unable to identify the specific submunitions used, but was able to identify other features, such as the cases used in a cluster munition attacks. A table highlighting the types of munitions used is provided below.

By far, the most common munition found in video footage of violations in Aleppo are barrel bombs. A recent Atlantic Council report finds that barrel bombs, improvised air-delivered munitions in which explosives and shrapnel are in metal barrels and dropped from aircraft, have caused widespread destruction and injury in Aleppo. The Syrian Network for Human Rights found that Aleppo was hit with 4,045 barrel bombs in 2016, with no fewer than 648 barrel bombs dropped in Aleppo in December alone. The Syrian Archive was able to definitively identify barrel bombs in 59 videos; however, the figure is likely to rise as analysis continues in the coming months.

Following the use of barrel bombs, cluster munitions appear in a total of sixty-six (66) videos. Despite being denied by the respective governments, there is longstanding evidence that cluster munitions have been in use by the Russian and Syrian Air Forces in the Syrian conflict. Cluster bombs, which are designed to spread submunitions over a large area, are likely to indiscriminately kill or cause injury to civilians. For this reason, many countries have banned the use of cluster munitions, signing the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions, although Syria and Russia have not. Nonetheless, as the Atlantic Council’s report highlights, “the use of cluster bombs in densely-populated civilian areas is illegal.” For this reason, the Syrian Archive generally categorised videos containing cluster munitions as unlawful attacks.

When analysing videos of cluster munition attacks, the Syrian Archive was, in some cases, unable to determine which specific type or model of cluster munition had been used or was present in footage, but was able to determine the presence of some type of cluster munition was used. In this case, the Syrian Archive found forty-one (41) videos. In two (2) cases, the Syrian Archive was unable to determine which type of cluster submunition was used, but was able to identify the model of cluster munition casings. In these cases, cluster munition casings identified were both model RBK-500.

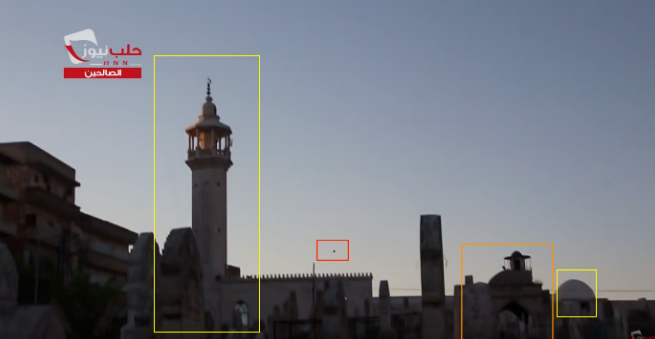

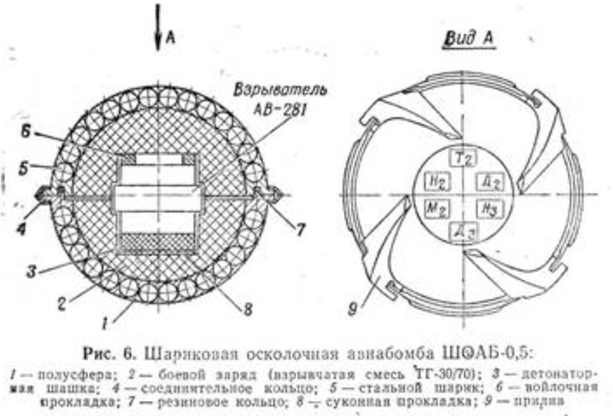

For many videos, the Syrian Archive was able to identify specific models of cluster submunitions. PTAB-1M submunitions were able to be identified in four (4) videos, ShOAB-0.5 submunitions were able to be identified in six (6) videos. The Syrian Archive conducted a long form investigation for one of the incidents which can be seen here. The incident was about an attack that targeted a gas station in Al-Saleheen district in Aleppo city on July 9, 2016. Below is a video published by Halab News Network features an aircraft involved in the same Al Saleheen attack, as well as the attack’s first moments.

In this same video, it is possible to identify the bomb falling from the plane onto Al Saleheen, as visible on the still from the video below.

We’ve geolocated camera positions from the Halab News Network video above.

Civilians, including children, are also seen running from the fire at the impact site in the same video, as seen in the following still.

On July 9, 2016, Aleppo Media Center additionally published a video on YouTube about the same attack which shows a man holding a cluster submunition ShOAB-0.5. See video frames below:

to determine cluster submunition ShOAB-0.5were used based on diagrams of the munition freely available online.

AO-2.5RT/RTM submunitions were also able to be identified in thirteen (13) videos. An in-depth investigation of cluster munitions is provided in the full report.

Chemical munitions, which are illegal, were identified in a total of fifty (50) videos. Specific chemical munitions were identified in a majority of these cases, with thirty-eight (38) videos featuring chlorine gas munitions. In twelve (12) cases, the specific chemical munition was unable to be identified but it was able to be determined that a chemical munition had been used.

Incendiary munitions, which are also illegal for anti-personnel use unless it is not feasible to use a less harmful weapons, have been identified in a total of 18 videos. Of these, in fifteen (15) cases, the Syrian Archive was unable to determine the specific incendiary munition used. Many times this is due to video footage taking place at night or from a distance. In the remaining videos, the Syrian Archive identified specific incendiary munition models, with ZAB-2.5S identified in all three (3) cases. An in-depth investigation of incendiary munitions is provided in the full report.

Missiles have been identified as being used unlawfully in a total of (5) videos. While the use of missiles is not prohibited in conflicts, IHL states they must be used only against legitimate military targets. Specific munitions were able to be identified in all five cases. Three (3) of these videos feature 9M79M Tochka munitions, one (1) of these videos feature FAB-500 SHN munitions, and one (1) of these videos features OFAB 250-270 munitions.

The Syrian Archive was similarly able to determine that drones were used unlawfully in two (2) videos of the same incident in which four civilians were killed.

Geolocation of violations

The Syrian Archive geolocated all 1748 videos in the dataset related to human rights violations in Aleppo city and the surrounding suburbs as shown below. Two types of geolocation have been conducted. The first is done by examining the video title, video footage, accent of the reporter as well as in cross referencing the incident with other reports about the same incident from different groups such as human rights organisations, humanitarian and medical organisations, and citizen journalists. In some cases, videos are cross-referenced with openly available satellite imagery, for example via Google Earth or Microsoft Bing Maps, and reference images are taken from the ground perspective.

Aleppo City

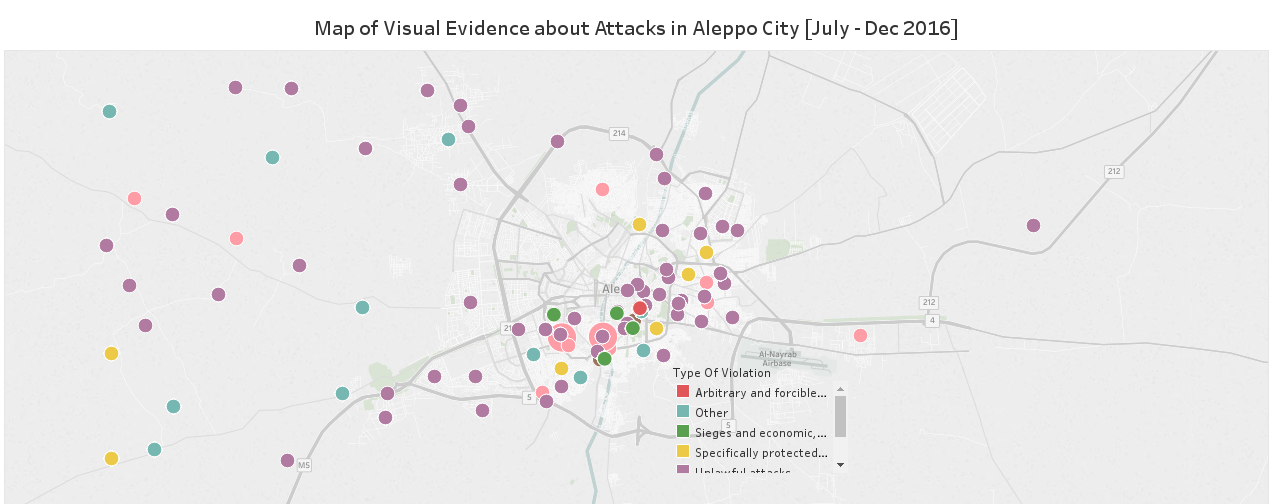

The map below shows the location of many reported attacks during the July – December 2016 period. The majority of violations identified were found to be committed by Syrian government and Russian military forces in eastern Aleppo. This includes the unlawful attack on Karem Al-Qaterji and the targeting of specially protected Al-Sakhour hospital, both of which were investigated in detail by the open source investigative website Bellingcat. The colors in the map refer to different categories of violations:

The use of illegal weapons in attacks carried by Syrian government forces, such as chlorine gas attack targeting Al Bab road in Aleppo city, was reported by different groups. Human Rights Watch has published a report of chemical attacks in Aleppo which included most, but not all, of the incidents mapped above.

Aleppo Suburbs

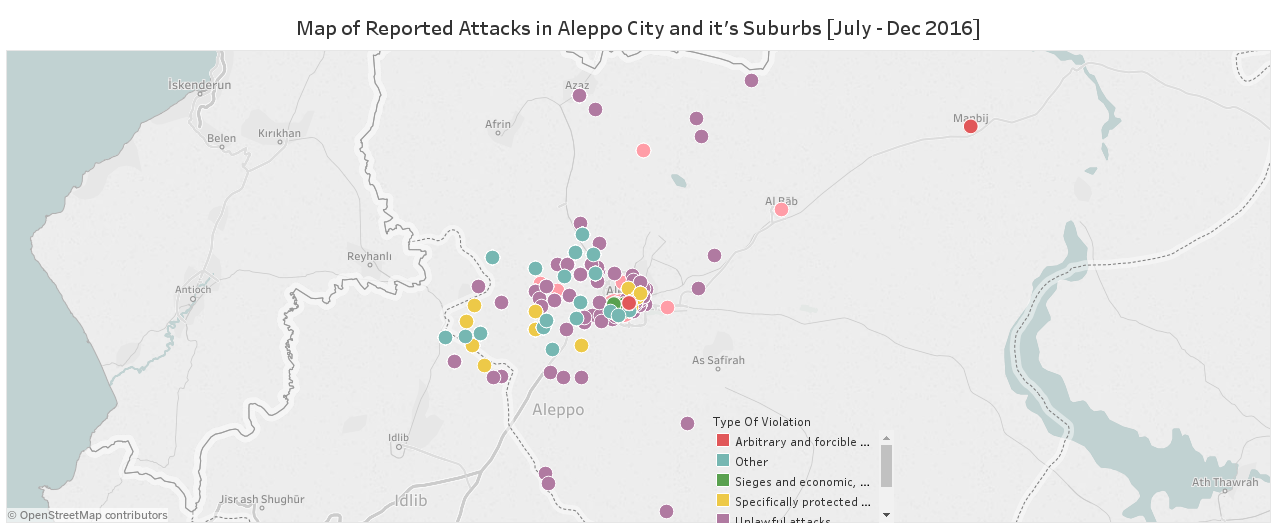

The map below shows that most of the violations in the Syrian Archive dataset occurred in the western countryside of Aleppo.

In-depth analysis of verified video evidence has led to finding the use of illegal munitions, such as chlorine gas, as a main tactic used by Syrian government forces to regain control of Aleppo city. Visual evidence concerning chlorine gas attacks was geolocated in the map above and is available on the Syrian Archive website. Human Rights Watch and Bellingcat have written and conducted extensive analysis on these incidents, for which the Syrian Archive assisted.

Additional violations include unlawful attacks against civilians, including an attack that hit a vegetable market in Awejel. They also include violations against protected persons and objects, such as mosques, schools, markets, bakeries, hospitals and Syrian civil defense centers. Complete analysis of attacks against protected persons and objects can be found on the pattern of attacks section of the report.

Below is a map that shows the geolocation of the videos and the type of object that has been attacked.

Further research

Though the battle for control of Aleppo city is now over, human rights research into violations committed during this time will continue for many years to come. The Syrian Archive strives for accuracy and transparency of process in reporting and presentation. That said, it is recognised that the information publicly available for particular events can at times be limited. Video datasets are therefore organically maintained, and represent our best present understanding of alleged incidents.

If you have new information about a particular event, are interested in learning more about research methodologies, find an error in our work, or if you have concerns about the way we are reporting our data – please do engage. You can reach us at info@syrianarchive.org.

This work is part of the Archive of Conflict Investigation project to collect, verify, preserve and investigate visual evidence of human rights violations in Syria and other conflict areas. Lessons learnt from this will also be applied to other investigations in the future, ensuring that the best investigations produce the best possible evidence.