Hasam Movement: A Short Analysis of an Egyptian Urban Insurgency

While Egyptian authorities have focused on preventing the expansion of Wilayat Sinai—an offshoot of the Islamic State—a new Islamist threat in the heart of Egypt’s cities is slowly emerging. On October 8, 2016, members of a group calling itself حركة حسم or Hasam Movement (Hasam can be translated as decisiveness) shot Gamal al-Deeb, a police officer and security official in Aman al Watani—Egypt’s domestic security agency—eight times (seven times in the torso and once in the head). According to the Egyptian Interior Ministry, the attack took place in Behira Province, and Hasam’s website (operated on a WordPress platform) added that al-Deeb was killed at around 12:30 AM local time. Following the shooting, the group posted an explanation in the form of a military communique on its website, suggesting that the group, albeit young, already considers itself to be an armed challenger to the Egyptian state.

![[source]](http://www.bellingcat.com/app/uploads/2016/10/1.jpg)

[source]

In addition to the group’s statement on al-Deeb’s execution, the group uploaded pictures of the target, supposedly to highlight its ability to gather intelligence without being picked up by Egypt’s domestic security forces.

![Image #1 shows target’s car parked in front of the target’s house [source]](http://www.bellingcat.com/app/uploads/2016/10/2.jpg)

Image #1 shows target’s car parked in front of the target’s house [source]

![Image #2 points to al-Deeb’s residence and his car [source]](http://www.bellingcat.com/app/uploads/2016/10/3.jpg)

Image #2 points to al-Deeb’s residence and his car [source]

![Image #3 captures al-Deeb after work, indicating Hasam’s success at extrapolating the target’s daily routine. [source]](http://www.bellingcat.com/app/uploads/2016/10/4.jpg)

Image #3 captures al-Deeb after work, indicating Hasam’s success at extrapolating the target’s daily routine. [source]

Perhaps most interesting about the Hasam Movement are its logo and the language it uses in its ‘military communications.’

The logo’s use of camouflage and the Kalashnikov rifle at the base of the logo strongly suggest that the use of violence to achieve political aims is not only endorsed but is actually central to the group’s success. The group’s use of military communications that cleanly categorize the time, type, and location of an operation hint, at least from a stylistic perspective, at a strong militaristic approach. Moreover, Hasam’s website boasts an entire category titled “بلاغات عسكرية” or military communications in English.

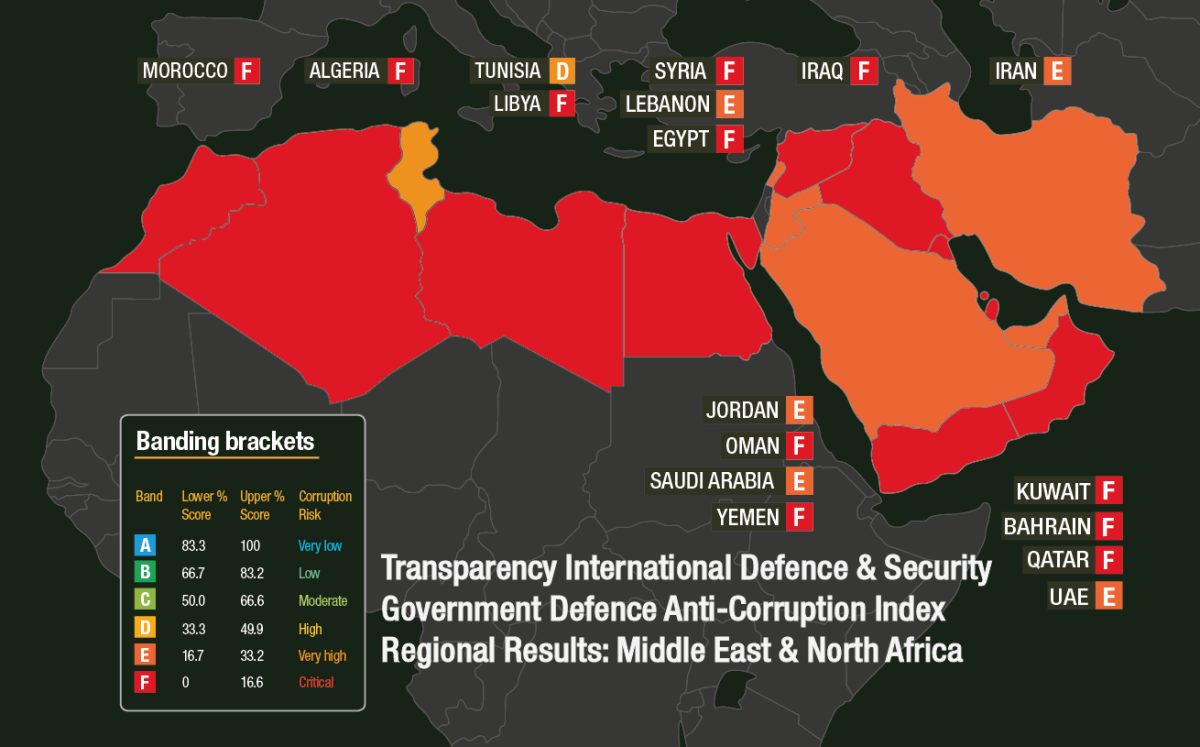

It is in this category where potential recruits or independent researchers gain insight into Hasam’s ambitions. In its “launch of the movement” document, the group proclaims that its resistance will result in “salvation from this hateful military occupation,” a reference to the military rule institutionalized by the Sisi regime. Its periodic reference to Allah and the use of Sura 9, Verse 14 (Fight them; Allah will punish them by your hands and will disgrace them and give you victory over them and satisfy the breasts of a believing people) at the end of each “military communication” imparts strong religious undertones. While Hasam presents an interesting form of Islamism, it seems as if its true ambitions are rooted in the eradication of Sisi’s authoritarian regime and not in building a global or even regional Islamic emirate. While Hasam does not exhibit overtly Salafist characteristics typical of an organization such as Wilayat Sinai, in reality, this might be a strategic move on the movement’s part. By not presenting itself as an Islamic fundamentalist organization bent on imposing a harsh interpretation of sharia within Egypt, not only are ordinary Egyptians more likely to sympathize with Hasam, but the assumption is made that Egyptians authorities will continue to focus on more extremist based threats, allowing Hasam to build a sustainable political and activist oriented infrastructure throughout Egypt.

Clearly, there is no way to tell what Hasam’s future entails. Some have speculated based on earlier statements released by Hasam that Rashid, a small northern city on the Nile, might be a sight for future assassinations. There is no way to verify this, however, the movement’s evolution and improvement in carrying out assassinations with precession are undeniable and therefore worthy of discussion.