An Open Source Analysis of the Fallujah "Convoy Massacre"(s)

From June 28 to June 29, aircraft of both the international Coalition (CJTF-OIR) and the Republic of Iraq targeted two large convoys of alleged Islamic State (IS) vehicles as they fled the outskirts of Fallujah in central Iraq. Concerns have been raised that the convoys were carrying not only IS militants, but also their family members that may have been killed in the attacks.

This analysis aims to provide a clearer overview of the events of June 29 and June 30, 2016 by cross-referencing all open source information available. This includes geolocations of footage released by both the international Coalition and the Iraqi Ministry of Defence (MoD), official statements, and media reports, especially a Washington Post (WaPo) article by Mustafa Salim and Thomas Gibbons-Neff (link) and Arnaud Delalande’s write-up in War Is Boring for which he interviewed Iraqi military pilots (link).

The situation in and around Fallujah

For over two and-a-half years, Fallujah was under the control of the so-called Islamic State. In the last days of June 2016, a combination of Iraqi forces managed to recapture the city following a month-long offensive. Despite that the city is now largely cleared from IS fighters, Iraqi forces still clash with some of them in the outskirts of the city.

Eissa al-Issawi, the mayor of Fallujah, said that he had obtained information that IS fighters would try to escape these outskirts and notified the Iraqi military, according to the WaPo-article. The first combination of airstrikes followed soon in an area south of Fallujah, where IS fighters allegedly had gathered to leave the city.

It is important to note that this was the first air attack on a convoy. From all open source information available, it is clear that there were at least two convoys: one north of the Euphrates River and one south of it. Therefore, this overview is structured along the lines of the two identified convoys: the northern convoy and the southern convoy.

The southern convoy

In the night of June 28, between 9:00 PM and 10:00 PM, Iraq’s military intelligence detected “the movement of numerous vehicles from Fallujah in a southwesterly direction along the road to Amiriyat Fallujah”, Delalande writes. Not much later Iraqi army helicopters continued to track the vehicles when “intelligence reports indicated that [IS] militants were fleeing Fallujah — seemingly explaining the huge convoy.”

The size of the convoy was according to Iraqi official sources around 11 kilometres long. That the convoy was indeed massive, can be seen in the following video that was tweeted by the official English-language account of the Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU), an Iraqi state-sponsored umbrella organisation composed of around 40 (mainly Shia) militias.

#Iraqi Army Aviation footage showing the longest #ISIS convoy at 11km long before it was decimated by #Iraqi forces pic.twitter.com/6fRkyUlhsM

— Iraqi PMU English (@pmu_english) June 30, 2016

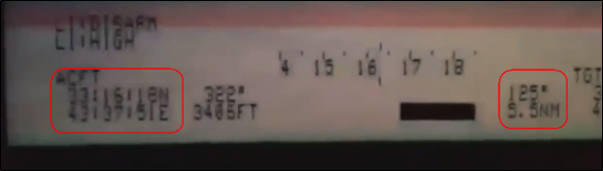

Interestingly, the video reveals much information as it shows the indicators for the aircraft on the left (ACFT; 33°16’18″N/43°37’51″E) and indicators for the target on the right (TGT; 55NM at 125° southeast). That means the helicopter was flying here, southwest of Fallujah, when it was filming the convoy a bit further southeast of the helicopter’s position.

The Iraqis subsequently informed their American colleagues, but CJTF-OIR “denied permission for its warplanes to attack the area in question, as the vehicles in question could be carrying civilians.” As a result, Delalande writes, Iraqi pilots took the initiative themselves and gained permission to attack from their superiors in Najaf a few hours later, with the “first two helicopters took off at 1:30 in the morning on June 29.”

Delalande’s information of Iraqi military pilots can be cross-referenced with official Iraqi MoD publications related to the attacks on its Facebook page and YouTube channel, which both state that the attacks started “exactly at 1:20 AM” (Arabic: “وتحديداً الساعة الواحدة وعشرين دقيقة”).

Besides, parts of the Iraqi MoD video compilation can be geolocated in the Hasai area (Wikimapia link) — a region southwest of Fallujah and on the road to Amiriyat Fallujah.

geolocation of an attack on cars [2:45-3:20] from this video https://t.co/BBhlhqCluo https://t.co/Xm4sYFoojX pic.twitter.com/7S2nPPNJCA

— Samir (@obretix) July 2, 2016

@Alex_de_M @trbrtc @obretix

It's probably here.https://t.co/hNJhqYntnz pic.twitter.com/myO6gwwsZT— הילל (@Luxfero_99) June 30, 2016

The 13 photos uploaded to the Iraqi MoD’s official Facebook page of the alleged aftermath on “over 426” IS vehicles in “the desert west of Amiriyat Fallujah” can also be geolocated to the Hasai area, in a village named Fuḩaylāt (Arabic: الفحيلات).

عاجل——وزارة الدفاع / الفريق أول الركن حامد المالكي قائد طيران الجيش يعلن عن تدمير وإعطاب أكثر من (426) عجلة…

Geplaatst door وزارة الدفاع العراقية op Woensdag 29 juni 2016

In addition to these geolocations in the Hasai area, the WaPo’s account also mentions the area, though spells it as “Hussay” and claims it is “northwest of Fallujah” from which vehicles fled towards the Syrian border. Though the name is correct (the Arabic name ‘الحصي’ can be transcribed to the Latin script in several ways), there is no “Hussay” north of Fallujah. Therefore, it appears that WaPo in fact refers to the same area as Delalande and the Iraqi MoD.

The attacks “lasted hours”, according to the Iraqi pilots interviewed by Delalande, and ”destroyed more than half the convoy, killing dozens of militants.” In the Iraqi MoD video, which includes footage from the aftermath from the ground, shows indeed a few bodies but even more clothes.

Several of the photos that appeared on social media, “clearly show that the convoy consisted of a mixture of civilian and military vehicles”, according to Delalande. Important to note is that the convoy also attacked the Iraqi aircraft, as the first 55 seconds of the Iraqi MoD video show. That footage has not been geolocated so far, but is likely to be from southwest Fallujah.

One the Iraqi MoD compilation video mentioned earlier, a large number of M79 Osa anti-tank unguided rockets is visible in the back of a small truck, as well as other weapons in another truck.

Other vehicles allegedly used for military purposes were also destroyed, such as “several bulldozers and a large number of so-called technicals” but other than that there is no footage of military vehicles. There is a possibility, Delalande rightly notes, that some of the vehicles carried the families of IS fighters — “which is apparently why the [US] initially refused to take part in the operation.”

But the convoy south of Fallujah was not the only convoy to be attacked on June 29, as geolocations of the videos and photos reveal, as well as the Delalande’s interview with Iraqi military pilots.

The northern convoy

A second round of airstrikes hit a different convoy of “around 30 vehicles [driving] in a northwesterly direction” (Delalande) near “Albu Bali neighbo[u]rhood” (WaPo), which is northwest of Fallujah.

WaPo cites a leader of local Sunni tribal fighters, Sheikh Faisal al-Issawi, who claimed they were contacted via walkie-talkie as an IS convoy neared their lines. The IS fighters said they did not come here to fight but wanted to pass through towards the desert. Al-Issawi attacked the convoy anyway, he says.

The location mentioned can be successfully cross-referenced with a part of the video released by the Iraqi MoD, thanks to a geolocation from Twitter user @obretix. From 0:55 to 1:23, the video shows a road in the desert northwest of Fallujah, north of the “Albu Bali” area (exact location on Wikimapia).

aftermath of coalition airstrike northwest of Fallujah [0:55-1:23] https://t.co/IKjHGFPvGY https://t.co/nbJlu0IL47 pic.twitter.com/A0PgHXpbDM

— Samir (@obretix) July 3, 2016

The Coalition also released a video on their official YouTube channel, saying it shows airstrikes on “[IS] fighters fleeing in a convoy near Habbaniyah, Iraq”. Habbaniyah is a town between Albu Bali and Fallujah. The location shown in the video was geolocated by Twitter user @Luxfero_99, just a few meters from the area geolocated above in the Iraqi MoD video.

@Luxfero_99 https://t.co/Wju5xGlN7j pic.twitter.com/P6eVFhRtcf

— הילל (@Luxfero_99) July 1, 2016

A statement of the MoD of the United Kingdom (UK) can also be cross-referenced with the events. On June 29 a Eurofighter Typhoon and two MQ-9 Reapers struck IS “terrorist[s] retreating from Fallujah”:

A Typhoon struck two vehicles and a large group of extremists with Paveway IV bombs west of Fallujah and two Reapers destroyed a further four vehicles and a group of fighters, using Hellfire missiles and a GBU-12 guided bomb. One Reaper observed the Daesh vehicles refusing to stop and pick up fellow armed extremists trying to escape on foot.

Two days after the attack, on July 1, the Iraqi MoD published a video showing the aftermath of the airstrikes from a ground perspective. The video shows the same section of the convoy as shown in the Iraqi MoD video from the air, as @obretix noted, and is thus a destroyed part of the northern convoy.

Both videos of this location do not show any military vehicles or small trucks with mounted guns. However, what appears to be the remains of a AKS short assault rifle (2), “given the folding stock”, can be spotted next to a teapot and a frying pan (1) in the Iraqi MoD video from the ground.

A part of the northern convoy was clearly destroyed, but what happened to the part of the convoy that was not destroyed and got away, is fuzzy.

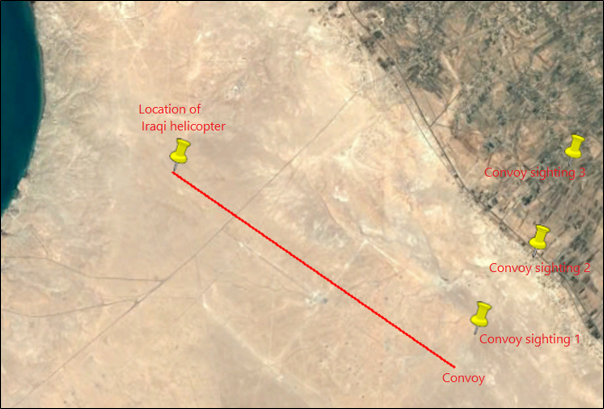

Delalande writes that reports came in of IS militants killing civilians east of Ramadi. On June 30, the Iraqi army deployed several Bell 407 scout helicopters and Mil Mi-28 gunships to ease the situation. The Iraqi aircraft came under fire, and subsequently the US Air Force ordered all helicopters to vacate the area, making place for CJTF-OIR fighter-bombers.

In the hours that followed, the “Iraqi army aviation flew dozens of medical evacuation sorties […] evacuating injured civilians from the vicinity of the coalition’s air ra[i]ds, including many children.” Later that day, CJTF-OIR spokesperson Col. Christopher Garver stated that the Coalition had struck “two major Islamic State convoys fleeing Fallujah over the last two days.”

Unlike the other combination of airstrikes, this round on the northern convoy was reported by civilians on the ground. On Facebook, the page ‘iraqi revolution’ posted that “the martyrdom and wounding of dozens of displaced families from Tarrah [Arabic: الطراح] to Ramadi Island [Arabic: جزيرة الرمادي], after the government and international aircraft targeted their vehicles.”

https://www.facebook.com/iraqRepublic/posts/1061994587203313

Airwars, a transparency project that tracks and archives the international air war against IS and other groups in both Iraq and Syria, puts the number of reported civilian casualties on 12 or more for the June 30 strikes near Ramadi, but labels the quality of reporting as “contested”. Airwars cross-referenced this event with an official report of the UK MoD:

With Daesh forces continuing to flee in defeat from their former stronghold of Fallujah, on Thursday 30 June Royal Air Force Tornado GR4s patrolled over the desert of Anbar province and located a group of terrorist vehicles a number of miles to the south-west of Ramadi. Attacks with four Brimstone missiles and a Paveway IV guided bomb successfully accounted for five trucks.

What the official reports of the Coalition do not mention is the number of fighters killed, though there are reports that there may be civilian casualties.

Alleged civilian casualties

The Iraqi MoD claims “hundreds” of IS fighters had been killed, while media reports suggest a lower number of around 250. It is hard to give an estimate of killed persons based on open source information, especially because all videos and photos show a minimal number of bodies.

Concerns have been raised about who have been killed: was it just IS fighters or were civilians also part of the convoy? Coalition spokesperson Garver said that this was indeed the reason why their aircraft had avoided a part of the convoy as they believed it could carry civilians.

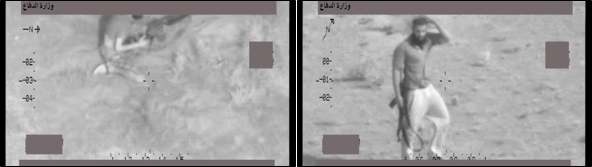

In the Iraqi MoD video at least two men can be seen carrying what appear to be Kalashnikov assault rifles, though the locations have not been verified to either the southern or the northern convoy so far.

The spokesperson of the Iraqi MoD claimed no women had been killed in the airstrikes, though their own video showed the body of a dead child near the location of the northern convoy.

The director of Airwars, Chris Woods, tells Bellingcat that incidents like these, where enemy forces flee en masse, are rare. But when such events occur, the claims that civilians were present “makes sense”. Woods says they might have been ordinary citizens trying to escape Fallujah, but thinks it is more likely that they were family members of IS militants. But, as Woods stresses, this does not change their status as non-combatants.

One of the unclarities of the events are the civilian deaths reported on June 30. It is unclear whether they are due to IS, the Coalition, or Iraq. Perhaps we will never know. “We still don’t know how many civilians died during the Highway of Death in Kuwait. Similarly, we may never know how many civilians died in the recent events, especially if the non-combatants were [IS] family members. They are non-combatants under international law, but whether they have been granted that status in reality is another question.”

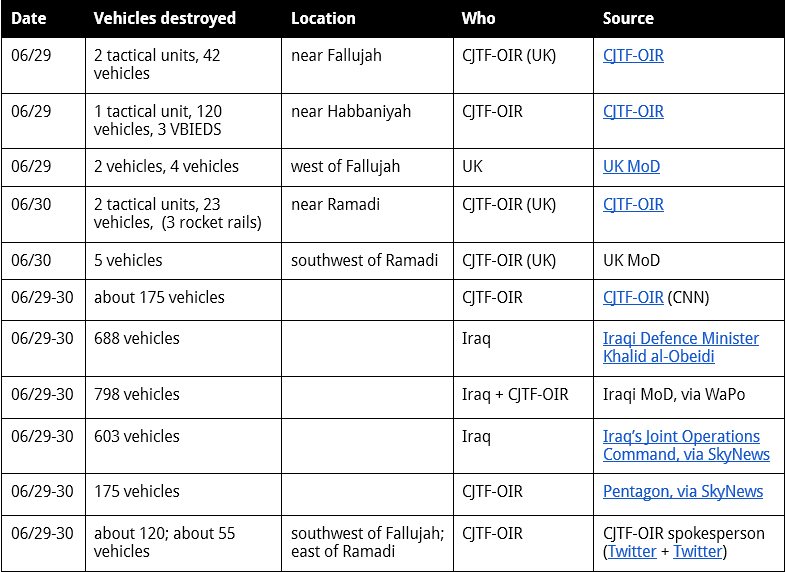

Number of vehicles destroyed

The number of vehicles destroyed varies significantly between the official statements of the authorities. This is a table with the different numbers that have been mentioned.

Humanitarian convoy

Besides the southern and the northern convoy struck by airstrikes, there was another convoy: a humanitarian one of an aid agency named Preemptive Love. At least two trucks were transporting “100,000 pounds of food for those who fled Fallujah” and were now stranded in camps around the city on the evening of June 28, an article on the organisation’s website reads.

But as the night fell, two trucks got stuck in “a massive rut”. The team split, one heading back to Baghdad and the other staying with the trucks. A little later, the team that stayed heard gunfire and “saw flashes of rocket fire in the distance”. Being in contact with the other part of the team that reached an Iraqi army checkpoint near Amiriyat Fallujah, they learned IS had “launched a counterattack” with vehicles moving in their direction:

The team guarding the trucks climbed down into a nearby ditch and pulled sand over themselves as ISIS vehicles began passing on the road. Our team leader counted about 80 vehicles with fighters bearing small arms.

Meanwhile, the other part of the team was still near the Iraqi army checkpoint but could not move further due to a lock-down as the fighting between Iraqi forces and IS continued. Just after dawn, they claim an airstrike from a Coalition aircraft hit very close to their position:

“We could hear the missiles coming on top of our heads,” said one of our team members. “After the first airstrike, we started running, trying to reach the checkpoint. But the soldiers aimed their guns at us and told us to stay back.”

Another round of airstrikes followed. Back at the aid organisations’ office they tweeted the last known coordinates of their team to the American embassy in Baghdad and US Central Command, while a reporter called her military contacts to alert the US.

.@USEmbBaghdad @CENTCOM pls STOP bombing our humanitarian aid team stuck @ Ameriyat alFallujah around 33.1338350,43.8054300 @preemptivelove

— Jeremy Courtney (@JCourt) June 29, 2016

That worked, according to Matthew Willingham, the organisation’s senior field editor: the Coalition “stopped short of acknowledging strikes at the exact coordinates we gave gave them.”

US forces have admitted they were conducting airstrikes on IS convoys in the area, according to Willingham. This is interesting as this is the southern convoy, of which the Coalition did not release any footage. The coordinates tweeted by Preemptive Love are a few kilometres southeast (Wikimapia) of other known locations of the southern convoy.

Since the attacks, access between Baghdad and the Iraqi province of Anbar has been even more restrictive than it already was, WaPo writes. As a result, humanitarian agencies are unable to deliver humanitarian supplies for “the tens of thousands” that have fled Fallujah and “are now stranded in desert camps”.

Analysis of open source information

Given all the open source information available concerning the incidents, several issues arise.

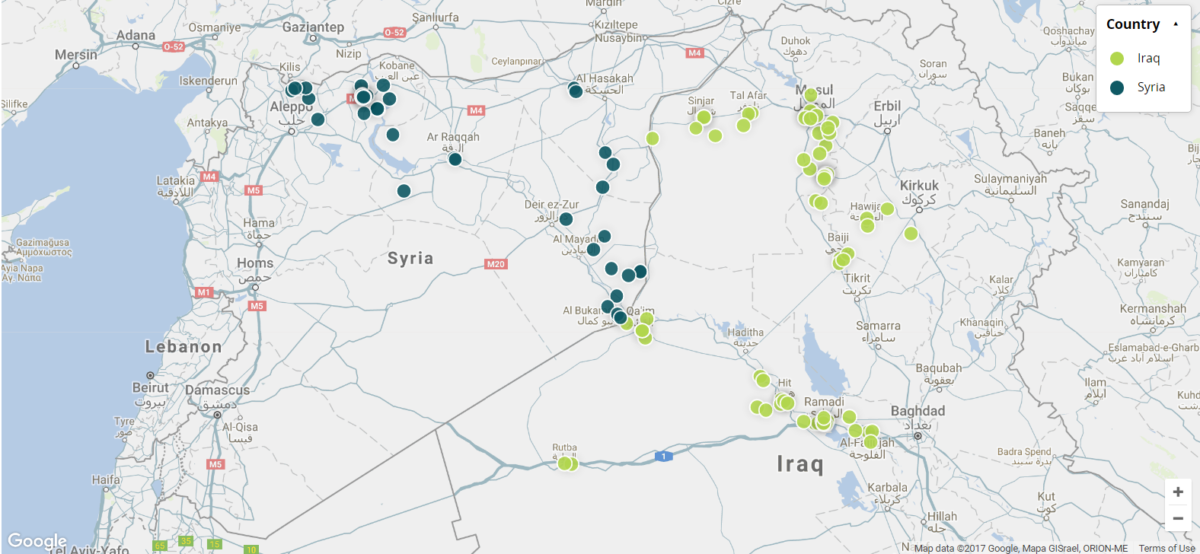

First of all is the confusion surrounding the events, which is not only indicated by the alleged airstrikes on the humanitarian organisations, but also by a tweet of the Coalition’s spokesperson. He tweeted several times about multiple convoys at multiple locations. With the above information, it seems highly likely that these convoys were probably the same: “east of Ramadi” is “near Habbaniyah”, while the spokesperson even tweets that is “southwest of Fallujah” (which it is not). To clear things up, here is an overview of the geolocated airstrikes on convoys around Fallujah.

As with regards to the northern convoy, the CJTF-OIR video sheem to show the convoy as being stationary, while the vehicles in the Iraqi MoD video were clearly driving. What is further noteworthy that in all videos not many bodies can be seen. Open source information cannot make this issue clearer, unfortunately.

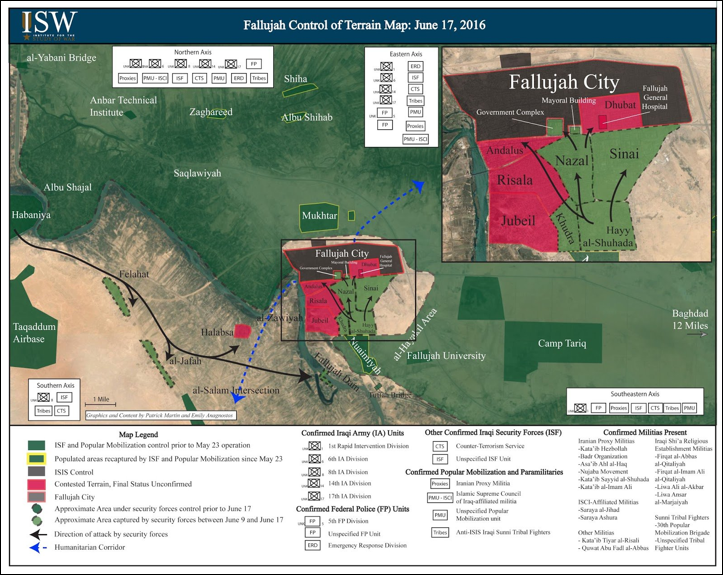

What else is remarkable is that both convoys managed to leave from Fallujah, while there were only two humanitarian corridors opened, one north and one south, where males were detained for processing. The humanitarian corridors are shown in blue on the Institute for the Study of War map below (note: the map shows the situation as of June 17, IS territorial control was heavily decreased by June 28).

How, then, did the convoys leave the city on lockdown? This is especially significant for the southern convoy, which, if it really came out of Fallujah city, must have crossed the Euphrates River. The most recent available commercial satellite imagery via TerraServer shows that only two bridges leading out of Fallujah were still intact – all other bridges in the vicinity of Fallujah were destroyed as of June 5, 2016.

According to Fallujah’s mayor al-Issawi, IS fighters that had fled Fallujah gathered in Hassai. If this is indeed the case, it means that the convoy would not have had to cross the Euphrates with vehicles. But even if that would be the case, such a massive convoy would not have attempted to flee without assurances that the army would not fight them, al-Issawi is cited as saying in WaPo: “They wouldn’t take such a risk unless they had a deal with some side […] Why would they drive more than 500 cars in an exposed agricultural area?”

In the past, Iraqi forces have left open escape routes for IS militants to escape the urban areas and go into the desert, according to WaPo. But the Iraqi MoD’s spokesperson Rasoul dismissed that claim as “nonsense”.

Conclusion

A survey of the open source information available shows us that at least two convoys were attacked by aircraft of both Iraq and the Coalition.

One convoy was travelling from Fallujah in southwesterly direction when it was struck several times by Iraqi aircraft in the early morning of June 29. In the same area, a humanitarian convoy claims to have been targeted by Coalition aircraft as well. The Coalition has made statements both saying they did strike in that area as well as statements that said they did not.

A second convoy was travelling from Fallujah in northwesterly direction when it was struck north of the Albu Bali area by both Iraqi and Coalition aircraft later that day on June 29. A part of the convoy appears to have been struck again a day later, closer to Ramadi. From there, Iraqi army aviation airlifted wounded civilians, though it is unclear who harmed them.

However, there are limitations to this open source approach, and there are still unanswered questions. How did the convoys managed to escape a city on lockdown? Who harmed the civilians near Ramadi that were airlifted by the Iraqi military’s aviation? Does this explain the lack of bodies shown on the videos? Why did the Iraqis attack the southern convoy despite a warning about civilians of the Coalition? Why was a humanitarian convoy allegedly targeted in the same area by Coalition aircraft nonetheless?

The author would like to express thank to the following Twitter users: @obretix in specific for his contributions to this article, as well as @Luxfero_99, @green_lemonnn, @Mr_Ghostly, and @ain92ru for the information they shared. The map is partly based on Liveuamap and ISW.

Updates:

- July 7, 2016, 21:13 GMT: Included the tweet with the coordinates of the Preemptive Love staff allegedly under attack by Coalition aircraft.