Keeping the Water Running in the Islamic State

The title has been changed to avoid implying any cooperation between the Syrian government and the so-called Islamic State.

The so-called Islamic State is said to be behaving like a conventional state in many ways. However, this open source investigation will show that the Syrian government — not Islamic State — keeps the water running in Islamic State’s de facto capital Raqqa and its countryside. The Islamic State takes credit for a service Bashar al-Assad’s government provides, as the group does not have the necessary expertise and competence to provide their own staff. An uneasy relationship for both parties, this arrangement has become even more uncomfortable by recent airstrikes on these facilities.

The provision of drinking water in Syria

The responsibility of water resources management in Syria lies with a number of ministries, such as the Ministry of Irrigation and the Ministry of Agriculture. There is also a special ministry for water-related affairs in Syria, the Ministry of Water Resources. It is currently headed by Kamal Sheikh, the tenth director of the Ministry since 1970. Each ministry has local bodies related to the central body over each of Syria’s fourteen governorates. With regard to drinking water and sanitation, this local institution is called the General Foundation for Drinking Water and Sewage (hereafter referred to as ‘the Foundation’).

The websites of some of these local institutions are regularly updated, such as Damascus, Latakia, and Hama. Others, like Raqqa, have very active Facebook pages. Raqqa and its governorate suffer from water shortages, just like the rest of northeast Syria. A massive drought resulted in the large scale unemployment of around 800,000 people, with many young men moving to the larger cities, thereby abandoning “whole villages and fields”. The Syrian government has reportedly invested billions of Syrian pounds in water projects during the last decade, for example near Tell Abyad and Ayn Issa, but none of this seemed to ease the water shortages.

The Euphrates River is the main source of drinking water and two of Raqqa’s most important water facilities are located along its south bank, as the map below shows: a pumping station (yellow) and a purification plant (red). There are also several water infiltration wells (blue) on both sides of the river. These are shallow wells which put or draw water into a natural aquifer outside the Euphrates’ riverbed.

Then there is the office of the Foundation which is located in the center of the city (green). The main building of the compound, that also has a water tower, was built in 2009, according to a report from eSyria. At the time, this office was “the fastest of all governorates”, an employee is quoted saying in the same article. Two years later, in 2011, it was reported that the Foundation started to experience difficulties. The contamination of the Euphrates River due to agricultural and industrial waste was said to be one of the institution’s major concerns. Consequentially, the Foundation invested heavily in the water infrastructure, owing a debt of 500 million Syrian pounds to the Syrian government in 2011. After another two years, the situation would become even grimmer for the Foundation.

Two photos from the General Foundation office in central Raqqa under construction in 2009. Photo: eSyria.

- Geolocated photos inside Raqqa’s water purification plant.

- Geolocated photos inside Raqqa’s water purification plant.

- Geolocated photos inside Raqqa’s water purification plant.

- Geolocated photos inside Raqqa’s water purification plant.

- Geolocated photos inside Raqqa’s water purification plant.

- Geolocated photos inside Raqqa’s water purification plant.

In 2013, Jabhat al-Nusra fighters took over the General Foundation offices in Raqqa, as these two YouTube-videos seem to show. Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, a fellow at the Middle East Forum, points out that this does not necessarily mean that the Nusra fighters subsequently managed water affairs in the city. Instead, civilian services were largely the responsibility of the local council while Nusra focused on their war efforts – unlike Islamic State.

IS collecting taxes for a service Assad provides

Islamic State took complete control of Raqqa in January 2014. It was the first major city to fall under the group’s control, thereby starting its state-building efforts on a large scale. The provision of basic services included water, as evident in leaked administrative documents that outline Islamic State’s principles for governing conquered territory and becoming a viable state, dubbed the “ISIS papers”.

For example, the Islamic State warned citizens of fines between 5,000 and 50,000 Syrian pounds if they take electricity from the water filtration plants near al-Bukamal, a city in Syria’s southeast. They also announced that employees of water services “must attend daily regular hours as usual” and required citizens to file their water tax forms every two months to avoid a fine. The group even set up an office for complaints regarding the quality of water in 2014. As evident in one of their Facebook posts, this action annoyed the Foundation. Another document, Specimen 9X, seems to suggest that the office was used as an Islamic State headquarters, as it asks the citizens of Raqqa to “register at the Islamic State HQ in the Water Foundation”.

- Specimen 8E: Public regulations (Albukamal area). Via al-Tamimi.

- Specimen 9X: Notification to Raqqa Residents: January 2014. Via al-Tamimi.

- Specimen 7G: Opening of office to receive complaints about services, Raqqa (2014). Via al-Tamimi.

The fact that the office may have been an Islamic State headquarters might explain why the office was allegedly bombed by the international coalition on January 5, 2016, as reported by Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently (RBSS) and ʻAmāq News Agency, Islamic State’s most important auxiliary media wing. The photos have been successfully geolocated at the office in Raqqa, and the claimed location can thus be verified. There were three reported casualties, an employee and two bodyguards, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR). This report from the SOHR is the only source for casualties, as both ʻAmāq and RBSS did not mention any casualties.

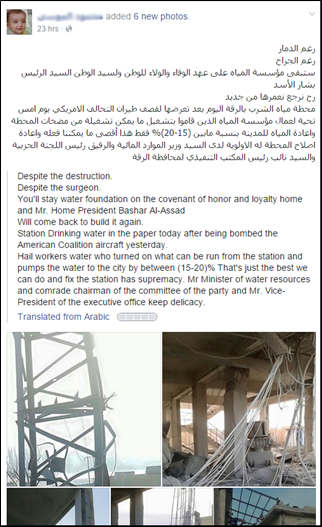

However, the Foundation also uploaded photos to Facebook, expressing anger over the bombardments and stating that they are going to rebuild it “once the Syrian army [gains] control over it.” This message might indicate that there were still employees of the Foundation working in the office, and that Islamic State either used part of the building as headquarters, or made it a headquarter while letting the workers of the Foundation to their work. The ISIS papers indicate that this may be an intentional strategy.

A photo of the Foundation’s office after it was allegedly bombed by the international coalition. It reads “We are going to rebuild it once the Syrian army [gains] control over it.” Photo: Facebook/January 11, 2016.

In the case that Islamic State does not have the required knowledge and capabilities, the documents show, it is necessary to preserve “the capabilities [personnel] that managed the production projects under the prior governments, whilst taking into account the need to place strict oversights and an administration affiliated with the Islamic State”. The section on the administration of wealth stipulates that it is necessary to put a plan in place that deals with the seizure of assets “that do not suffice without existence of an administration managing the interests and managing the crises”.

In short, this means that when Islamic State does not have the required knowledge to sustain facilities, government servants will do the job. And that is exactly what is happening in Raqqa, and, possibly, in other major water infrastructure facilities as well. The existence of technical professionals in Islamic State is not totally unheard of, notes al-Tamimi: the group has employed a Sudanese engineer in the past to operate a dam along the Euphrates. If Islamic State actually had the technical expertise to deal with infrastructure damage, this would likely have been showcased. While employing a pragmatic approach, the Islamic State does not mention is that the “prior government” continues to pay the salaries of the personnel working in those facilities.

Documents uploaded on Facebook by the Foundation and its director – who himself resides in a city under governmental control – show that since Islamic State took control of Raqqa, the Assad government has continued paying salaries. At least, this is the case if employees come to pick up their salaries. Since the city fell to Islamic state, employees of Raqqa’s water facilities must travel around 260 kilometers from Islamic State held territory to Hama. Earlier, in August 2013, it was also possible to pick up salaries and pensions in Hasakah.

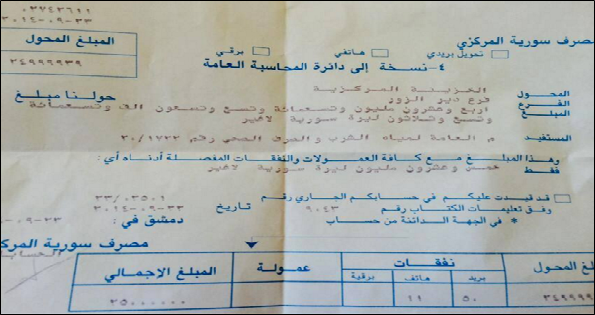

After arriving at the Hama office, employees have to identify themselves with a signature and a stamp. Pay-day is every few months, so it seems. The Foundation first has to wait for money from the government before it can pay salaries and pensions to its employees – when that money is there, the general director of the Foundation posts a photo of the bank note showing a transfer of 35 million Syrian pounds from the Ministry to the Foundation in Deir el-Zour, which might suggest Raqqa and Deir el-Zour are currently managed by the same person(s).

The entrance to the Water Foundation office in Hama, where the salaries to workers from Raqqa are being paid. Photo: Facebook/August 18, 2015.

Employees line up in the Hama office in August 2015 to receive their salaries. Photo: Facebook/August 18, 2015.

A bank transfer from the Central Bank of Syria to the Foundation in Deir ez Zor, ordered by the Minister of Water Resources. Photo: Facebook.

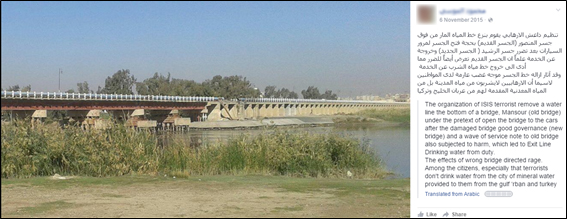

It seems that Islamic State has tried to take advantage of that hurdle by offering to pay employees their salaries instead. The Foundation warns its staff not to accept those payments, saying they have “already suspended the salaries of 34 employees because they did accept [these] salaries [from] the armed terrorist organisations” on Facebook. On November 7, 2015, the director of the Foundation posted that Islamic State was even preventing workers to travel to Hama to pick up their salaries. He also mocked Islamic State for not drinking “water from the city” but “mineral water from the Gulf [countries] and Turkey.”

Islamic State prevented workers from to pick up their salaries in Hama, according to a Facebookpost of the director of the Foundation on November 7, 2015.

The director accused Islamic State members of drinking mineral water from the Gulf countries and Turkey, instead of drinking water from the city’s water facilities.

At the same time, Islamic State tells the inhabitants of Raqqa “not to pay [water] fees to any other faction”, so it can collect it can take advantage of the taxes. In August 2015, Islamic State even raised the water tax from 700 to 1,000 Syrian pounds, per RBSS. Interestingly, Islamic State has used papers of the Foundation, rather than their own papers, as RBSS reported in August 2015. The Foundation referred to seemingly the same incident on its Facebook page, saying that those papers “don’t belong to us but belong to ISIS” saying that it is them, not Islamic State, covering the salaries and work supplies needed. Islamic State thus charges people for services that the Syrian government is providing.

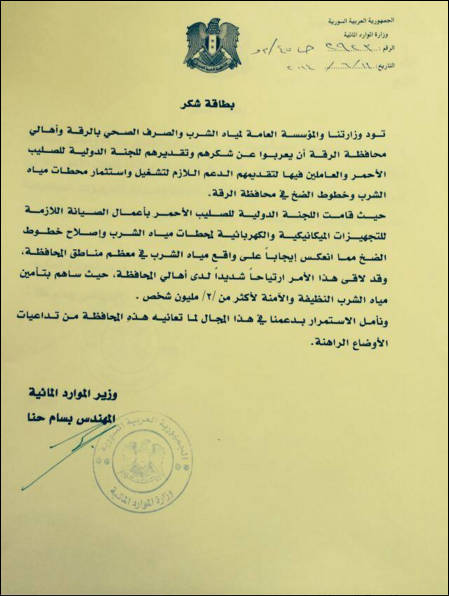

All of this does not make the water quality of Raqqa any better, as the city and its surroundings often suffer from interrupted provision of potable water. These interruptions are caused, according to the Foundation, due to power outages, high water, people stealing electricity, the installation of sprinklers in the city, and the construction of buildings higher than six stories. A high number of cases of diarrhea, dysentery and kidney failure has been reported among children in Raqqa by Tishreen News, a state-owned newspaper based in Damascus in November 2015. Though the Foundation says it receives “little funds” from the Ministry to counter such problems, it does receive international aid with sodium hypochlorite, sand filters, and sterilisation filters. Photos of such deliveries have been posted on Facebook. A ministerial document from July 2014 thanks the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) for providing disinfection materials for drinking water to Raqqa. Oxfam, in cooperation with UNICEF and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, also cooperates with the Syrian government with regards to water resources.

In this letter, the Ministry of Water Resources expresses its gratitude towards the ICRC for their work on fixing and maintaining the technical and electric devices which provide clean water for Raqqa. Photo: Facebook.

- Delivery of about a hundred tons of sterilisation material in January 2016, according to the director of the Foundation.

- Delivery of about a hundred tons of sterilisation material in January 2016, according to the director of the Foundation.

- Delivery of aid.

- Delivery of about a hundred tons of sterilisation material in January 2016, according to the director of the Foundation.

- Delivery of about a hundred tons of sterilisation material in January 2016, according to the director of the Foundation.

- Water pump reportedly installed by ICRC Syria, uploaded to Facebook on April 14, 20154.

But even with these aid deliveries, the water situation in northern Syria remains disastrous. And this situation has only got worse when water facilities, besides the aforementioned office, started to get bombed.

Airstrikes on water facilities

Over the past half year, at least four water-related facilities have been bombed, excluding the alleged international coalition bombing of the Raqqa office. The strikes seem to have started with two airstrikes in November: one allegedly by the coalition on the Abū ‘Amr water pumping station in the Deir el-Zour governorate, and the other by the Russian Air Force on Aleppo’s main water treatment plant. Both have been extensively analysed, and while no conclusive evidence could be found for an American targeting of the pumping station, the Russian Ministry of Defence self released a video showing they targeted the facility. Interestingly, the plant, which also provides water to government-held neighborhoods, was reportedly repaired by regime engineers within five days. There seems to have been another strike on the same day near Maskana, just southeast of the treatment plant.

The most recent event occurred on March 2, 2016. On March 2, 2016, a 57-second video was uploaded by ‘Amāq, claiming to show the destruction of the “water foundation” near Raqqa by “Russian cluster bombs”. The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) followed with a similar report, stating that the Russian Air Force had bombed “the water institution in Kasret Farj village” in the Raqqa Governorate, “destroying it almost completely and rendering it inoperable”. The ʻAmāq video could indeed successfully be geolocated and identified as Raqqa’s water purification plant. However, the claim that the purification plant became inoperable cannot be verified.

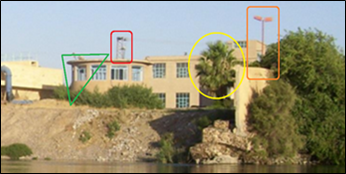

A photo of the water purification plant from the Raqqa Facebook, shows several features that can be matched the ʻAmāq video and the satellite imagery: the antenna (red), the circular building (green), the distinctive lamp post (orange), and the palm tree (yellow).

A still from the ʻAmāq video shows several features that can be matched to both Google and Microsoft imagery: a wall (blue), a little building (purple), and a part of the pavement (pink).

Satellite imagery from Google Maps (October 10, 2014; left) and Microsoft Bing (January 2013; right).

The large piling up that can be seen in the video might be sacks of aid, that have been there at least since March 9, 2015, TerraServer satellite imagery shows.

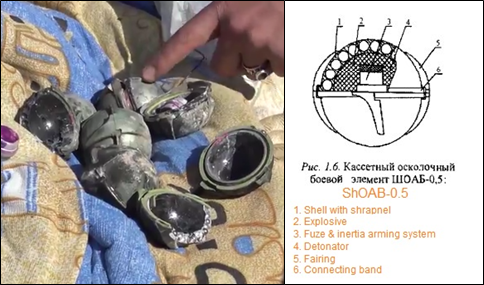

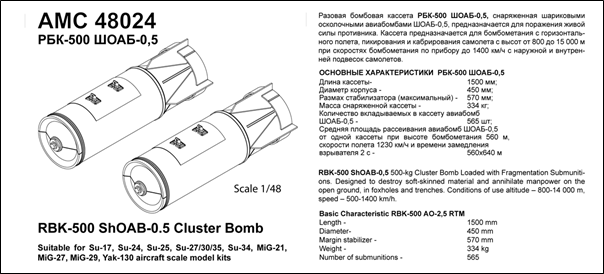

The ʻAmāq video also includes two shots of different objects. The shots are, however, isolated from the surroundings and it is therefore not possible to say whether the objects were filmed at the same location. Nevertheless, it is worth identifying these objects. The first set of objects can be identified as remnants of ShOAB-0.5 or ShOAB-0.5M ball-shaped anti-personnel submunitions of Russian fragmentation cluster munition. These submunitions are loaded into RBK-500 cargo bombs which can carry a nominal of 565 submunitions. ShOAB stands for ‘spherical fragmentation aircraft bomb’ (Russian: SHarikovaya Oskolochnaya Aviatsionnaya Bomba) and is a copy from the American BLU-26 bomblet. The second object is most likely the chasing of a RBK-500 cluster bomb in which the above identified submunitions are loaded, as reference images seem to suggest.

The first set of objects can be identified as remnants from ShOAB-0.5 or ShOAB-0.5M ball-shaped anti-personnel sub-munitions of Russian fragmentation cluster munition.

The second object, which is most likely a part of the chasing of a RBK-500 cluster bomb. The image has been vertically rotated to make it easier to read the inscriptions. Still from Amaq-video.

A sketch of a RBK-500 ShOAB-0.5 cluster bomb. Image: Karopka.ru.

Cluster munitions can be delivered from the ground by rockets and artillery, or dropped from aircraft. It is not possible to determine whether the airdropped cluster munitions were dropped by Russian or Syrian aircraft, or both. One can only make assumptions as to why cluster munition was used in this area. question is why anti-personnel fragmentation cluster munitions were used on a large compound like this water purification plant.

There have been seven persons killed and approximately seventy wounded, according to Syrian News Network, which also claimed that Russian planes were responsible for the attack. ʻAmāq mentioned the same number of casualties in their news brief. The activist group RBSS put the number of wounded a little bit lower, at sixty. The group also published a list of names later that day. The Syrian Network for Human Rights put the victims of the attack much lower with five victims, including a girl.

Interestingly, the director of the General Foundation blamed in first instance the international coalition for the airstrike when he uploaded photos of the destruction to Facebook on March 3, 2016. He deleted the post a few days later.

On December 23, 2015, Major-General Igor Konashenkov, spokesperson for the Russian Ministry of Defence (MoD), denied allegations that the RuAF stockpiled cluster munitions in Syria. However, the Conflict Intelligence Team has identified cluster munitions in photographs and videos taken at Russia’s Hmeymim airbase in Syria. Human Rights Watch has also identified the use of cluster munition by the RuAF in Syria. Besides the cluster munition, it seems that other bombs have been dropped as well, because other buildings on the compound are completely destroyed.

Just as Islamic State does not have the knowledge to operate the water facilities, it does not seem to be able to repair damage to the facilities either. Al-Tamimi has noted that there have been regime collaborators in Iraq’s Mosul, which is “hardly surprising: after all, in its propaganda messaging, [Islamic State] has bragged about its speed at repairing damaged water infrastructure […in…] Mosul in the face of government forces’ bombing.” This would be close to impossible for Islamic State to accomplish without the help of those working in the water system – which includes alleged collaborators. The Syrian government, however, seems to send official and other state employees themselves.

Conclusion

Open source evidence proves that it is not the Islamic State, but actually the Syrian government that is providing Raqqa with drinking water. Staff of the water facilities travel from the “caliphate” to government-held territory because Assad pays their salaries and pensions, though it is Islamic State that collects the taxes. Al-Tamimi believes that through this arrangement, the Syrian government tries to retain leverage. The Iraqi government had a similar approach and paid salaries to civil servants in IS-held Mosul up to July or August of 2015. In 2014, an activist from Deir el-Zour told the Washington Post that Islamic State “is not this invincible monster that can control everything and defeat everyone” as it fails to provide basic services like drinking water. This failure of providing a basic service like water seriously questions the Islamic State’s ability to govern in the territories it controls.

What is perhaps most interesting is that these water facilities — staffed and paid for by the Syrian government — were at least twice allegedly bombed by the Russian Air Force. Though the first one might have been a mistake, one can only speculate as to why the second facility was bombed.

The author can be contacted at @trbrtc or at christiaan.triebert@gmail.com. He would like to thank Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, Chris J. Woods, Hadi al-Khatib, Aric Toler, and Nathan Patin for their help and feedback.