Chemical Crises: A Timeline of CW Attacks in Syria's Civil War

On April 16, 2015, the United Nations Security Council heard firsthand accounts of doctors who treated the most recent victims of a wave of Assad’s trademark barrel bombings. The Idlib Governorate in northwestern Syria, a region controlled mostly by opposition forces, was bombarded over several weeks in March by dozens of AIEDs dropped from SyAAF helicopters — many containing toxic chlorine gas.

The wave of attacks killed “at least 206 people, including 20 civil defense workers,” according to Human Rights Watch. Just a few days earlier, the United Nations passed Resolution 2209 condemning the use of chlorine gas in Syria, and claiming they would take action as per Chapter VII of the United Nations charter if chlorine use continued.

“If there was a dry eye in the room, I didn’t see it,” said Samantha Power, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, in a press interview condemning the attacks. She said the United Nations would take every step possible to hold accountable those responsible for the attacks — a decent consolation for the 206 victims in Idlib.

But this wasn’t the first time the international community promised retribution for Assad’s use of chemical weapons.

In August 2012, a year before the deadly sarin gas attacks on the suburb of Ghouta, Damascus, which killed almost 1,500 Syrian citizens — many of them women and children — President Obama said Assad’s use of chemical weapons presented a clear “red line” for action by the United States. Obama clarified this statement in September 2013, only a month after the attacks, saying:

“The world set a red line when governments representing 98 percent of the world’s population said the use of chemical weapons are abhorrent and passed a treaty forbidding their use even when countries are engaged in war. […] Congress set a red line when it indicated that — in a piece of legislation titled the Syria Accountability Act — that some of the horrendous things that are happening on the ground there need to be answered for.”

Accountability for the Assad government’s red line violation came in the form of an OPCW decision, with support of the United States, Russia, and the United Nations, providing a directive for the destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles. Syria agreed, and in October 2013, signed and ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention prohibiting the production, stockpiling, and usage of designated chemical weapons.

Outspoken critics, including the editorial board of the Christian Science Monitor, said the reactive destruction of Assad’s chemical weapons stockpiles wasn’t enough punishment for the Ghouta attacks — that economic and political sanctions, perhaps even military action, was the only suitable response for Assad’s violation of the red line set by the world when they convened in 1992 to sweepingly condemn the use of chemical weapons on any scale.

Others said stockpile destruction was just enough, that foreign intervention could only lead to more issues. Yet despite Syria’s ratification of the Chemical Weapons Convention and agreement to destroy their existing stockpiles, use of chemical weapons has only increased during the Syrian Civil War. As in the most recent wave of attacks in Idlib, the delivery method of these attacks is becoming increasingly more deadly — and Syrian citizens increasingly more demoralized.

Provided the United Nations follows through on their threat of action, the international community’s reaction to the Idlib attacks will certainly be unique: punishment may be handed down for the first time since 2013 for Assad’s use of chemical weapons.

But in the process of determining punishment for the most recent attack, it would be befitting for the United Nations to take a look at some other chemical attacks that have occurred since the inception of the Syrian Civil War to see whether they, too, violate international law. Including the Ghouta attacks in August 2013 and the Idlib barrel bombings in March 2015, there have been numerous chemical attacks throughout Syria, resulting in thousands of deaths. Below are a timeline of the most prominent attacks, up until the Idlib incident.

BZ | Homs | December 23rd, 2012

Video from an opposition media group purportedly showing a victim of the Homs attack

Marking one of the first reports that the Syrian government had deployed chemical weapons inside its own country, a secret State Department cable obtained by Foreign Policy and signed by the U.S. consul general in Istanbul concluded a “compelling case” that BZ was deployed in Homs in December 2012.

BZ is the common name for a non-lethal incapacitating agent, 3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate, controlled under Schedule 2 of the Chemical Weapons Convention. The agent is designed solely for incapacitation and disorientation, and thus has a relatively high margin of toxicity, but in general can cause confusion, stupor, and hallucinations. The Chemical Weapons Convention controls and limits the production of BZ under Schedule 2, meaning any party to the convention is prohibited from producing the chemical for military purposes, but due to BZ’s non-toxicity does not include the chemical under its list of Schedule 1 substances.

The investigation into BZ use was reportedly conducted by an NGO hired as one of the State Department’s facilitating partners inside Syria, and included on-the-ground reports from witnesses and “other first-hand information.”

“it’s incidents like this that lead to a mass-casualty event,” said an Obama administration official who detailed the cable to Foreign Policy — warning if the U.S. government didn’t react strongly to this incident of chemical weapons use, Assad would only be emboldened.

Sarin | Khan al-Assal | March 19th, 2013

Victims of the Khan al-Assal attack treated in a local hospital, March 2013

A victim of overshadowing by the far more deadly Ghouta attacks in August 2013, the Khan al-Assal administrative district of Aleppo became home to the first widely acknowledged use of a nerve agent in the Syrian Civil War. The attack resulted in at least 20 fatalities and over 80 injuries. Many of the killed and injured were civilians, but a significant portion were government soldiers — leading to disputes between which party to the conflict carried out the attack.

In February 2014, a UNHRC Commission of Inquiry released a statement concluding that sarin had been used on multiple occasions in Syria, and that the Khan al-Assal attacks bore similar hallmarks to Ghouta. However, the United Nations did not identify any perpetrators.

Russia, as in Ghouta several months later, claimed the attack was carried out by the opposition using Basha’ir-3 rocket-propelled unguided missiles, parroting claims made by Syrian state news agency SANA immediately after the attacks.

The United States claimed the opposite, with US Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes stating that the “Assad regime has used chemical weapons, including the nerve agent sarin, on a small scale against the opposition multiple times in the last year” — including on March 19th in Khan al-Assal.

In an interview with former UK CBRN Forces Commander Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, Eliot Higgins and de Bretton-Gordon concluded that the scenario of a DIY rocket being used by opposition forces as per Russian claims was “highly improbable,” simply due to the delivery methods of sarin and the level of sophistication involved in deploying the agent. Still, the incident remains unresolved on an international level.

Sarin | Saraqeb | April 29th, 2013

One of the canisters identified in the aftermath of the Saraqeb attack

Shortly after noon on April 29th, the town of Saraqeb in the Idlib Governorate was bombarded from a government-held position by conventional munitions. Later, eyewitnesses spotted two canisters dropped from a helicopter hovering over the town.

The canisters were reportedly emitting a trail of smoke as they fell, with a strong odor eyewitnesses described as “suffocating.” Mostly due to the small scale of the attack, Saraqeb was not acknowledged widely by media at the time, but reports have shown at least 19 casualties and one death.

Because of the agent’s delivery method and lack of fatalities reported, the canisters used in the attacks did not seem to contain a lethal nerve agent such a sarin. However, Saraqeb later became one of five locations confirmed by the United Nations to have experienced a sarin attack between March and August 2013, along with Ghouta, Jobar, Khan al-Assal, and Ashrafiat Sahnaya.

Sarin | Ghouta | August 21st, 2013

A spent Volcano rocket purportedly used in the attack

The most infamous of all Syrian chemical attacks, and perhaps the single most analyzed incident in Bellingcat’s brief history — the August 21st chemical attacks on Ghouta, Damascus. With over 5,000 people affected by the attack and 1,500 killed, according to estimates by US intelligence and various NGOs, Ghouta sparked the most extensive international reaction of any incident in the Syrian Civil War.

Blame for the Ghouta attacks has been pinned almost universally on Assad’s Syrian Arab Army, but there are a few holdouts — namely the more contrarian conspiracy sites, fueled by an official insistence from the Russian government that the attacks were carried out by the opposition. Still, at least a dozen independent sources, including six governments, have formally placed culpability on the Syrian government.

Following Assad’s ratification of the Chemical Weapons Convention in the aftermath of Ghouta, there has been an upswing in the use of toxic and often fatal chlorine gas, the manufacture of which isn’t prohibited by the Chemical Weapons Convention, over more traditional nerve agents like sarin.

Chlorine | Kafr Zita | April 11th, 2014

Cylinders containing an unknown substance found in the aftermath of the attack

In October 2014, the UNHRC confirmed use of chlorine gas via barrel bombings in the town of Kafr Zita, an incident which resulted in 100 casualties and three deaths — all civilians.

Due to its strategic location 40km north of Hama and relatively stable territorial control by the Syrian opposition, Kafr Zita has long been the subject of attacks by the Syrian government in its attempts to drive the opposition out. At the time of the April 2014 chlorine attacks, Kafr Zita was the forwardmost major town held by the rebels in relation to Syrian government-controlled territory, which stretches from Hama to Damascus.

Given the trademark use of barrel bombs as a delivery device for the chlorine, blame was placed by most critics on the SyAAF, while the Syrian government itself, through its state-run news agency, placed blame on JAN brigades — despite JAN not having an air presence. In a report for Britain’s Telegraph, the aforementioned CBRN specialist Hamish de Bretton-Gordon concluded via analysis of on-the-ground samples that chlorine was used in Kafr Zita. Further investigation by the Telegraph concluded, similarly to the UNHRC, that the source was likely barrel bombs dropped from SyAAF helicopters.

Chlorine | Idlib | March 16th-31st, 2015

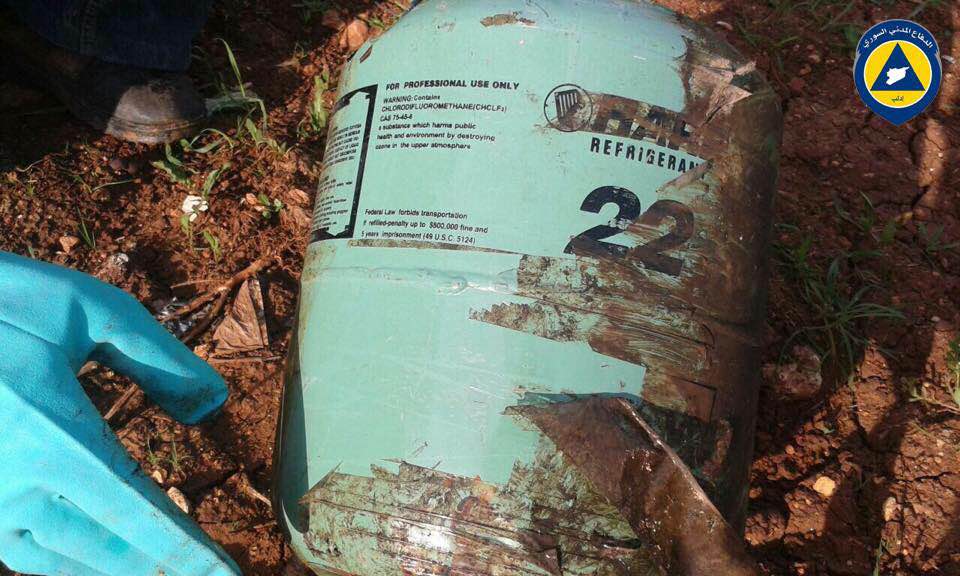

Refrigerant canister found among the remnants of a barrel bomb in Idlib, March 24th, 2015

On April 14th, 2015, Human Rights Watch published a report accusing the Syrian government of using toxic chemicals including chlorine in a wave of six attacks in the Idlib Governorate between March 16th and March 31st, 2015. HRW called on the United Nations to “respond strongly” to the attacks, and to “act decisively to establish responsibility.”

The wave of attacks resulted in 206 casualties, and six civilians were killed in one incident of barrel bombing on March 16th. According to on-the-ground interviews from HRW, unlike traditional barrel bombings (which are particularly devastating for the Syrian populace simply due to their unpredictable nature), none of these attacks resulted in explosions — in many cases, locals only realized something was wrong when hospitals began filling up with patients showing signs of chlorine gas exposure.

The United Nations reacted strongly to the attacks, and promised decisive action. But with Russia as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, decisive action may remain indecisive for quite some time.

Since writing this article, yet another video has emerged purportedly showing a chlorine attack on a village in northwest Syria, in rebel-controlled territory.

The physical properties of the plume shown in the video are consistent with chlorine, and if the video is accurate, will make this incident the second example of weaponized chlorine use since the United Nations condemned the use of chlorine in Syria last month.

What is Assad’s end game? He clearly believes the United Nations will fail to follow through on their threats of action, yes, but the increased use of chemical weapons — a much less effective but much more demoralizing agent than conventional munitions — show desperation on the part of the government. With extensive territorial gains from foreign militants, attrition of Syrian armed forces across the country, and the largest non-ISIS rebel offensive since at least 2014, there is an air of uncertainty and perhaps even futility surrounding Assad’s military actions. He is four years into a war with no foreseeable end, and wariness has hit all sides hard. But Assad made the decision long ago to fight until there’s no fight left, even if it means using chemical weapons to do so.