Implications of Colombia's New ELN Peace Talks

The Colombian government has announced that the ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, Spanish for “National Liberation Army”), the second largest guerrilla army in Colombia, will have peace talks starting on October 27. After the FARC peace agreement was narrowly rejected by Colombian voters in the October 2nd plebiscite, the government hopes that talks with the ELN may help salvage the peace process. Indeed, making peace with both guerrilla groups would alleviate fears of the ELN taking over FARC’s territories and operations. However, the ELN’s inclusion could also complicate the peace process and the post-conflict situation.

Overall, the ELN follows a more ideological agenda than FARC with regards to peace negotiations. While FARC’s demands revolved around rural reforms, amnesty, and legal political participation, the ELN has stated on its radio station’s twitter account, @ELN_RANPALcolom, that the Colombian “oligarchy” must include the “excluded peoples” of Colombia in democratic governance, reduce inequalities between the rich and poor, and provide greater social justice in order for there to be peace. Furthermore, the ELN rejects any pretenses of an “express peace process” within limited time spans and threatens to continue armed resistance if the government falls short in the peace process. With a more ideological agenda and generalized demands than FARC, it may prove difficult for the ELN and the government to reach compromises.

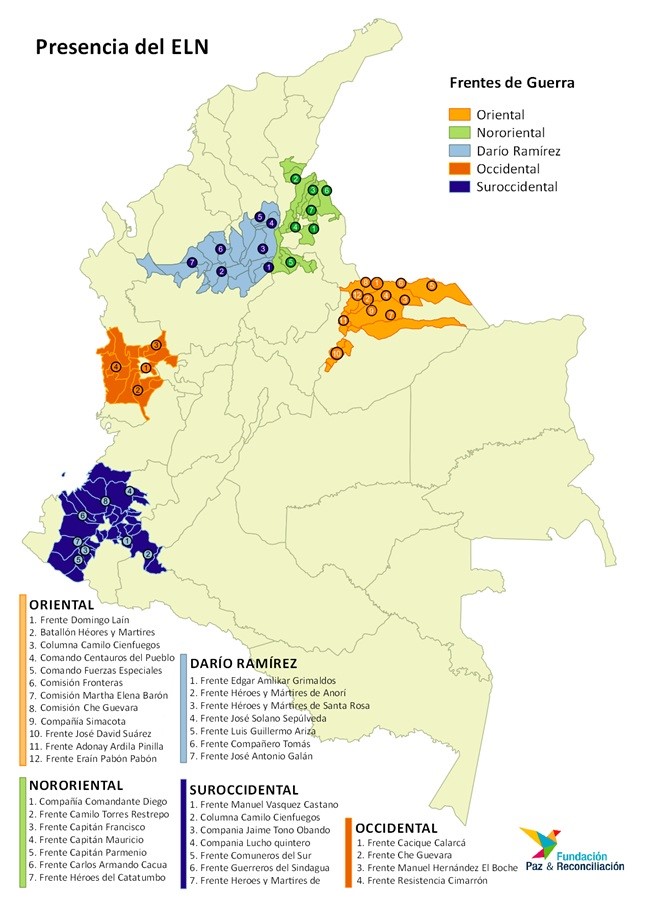

Additionally, the ELN’s decentralized command structure could also undermine the peace process. While the ELN is headed by its central command (“Comando Central,” abbreviated as “COCE”) consisting of four top commanders, its organization is divided into five regional “Frentes De Guerra” (War Fronts) with 37 sub-fronts across Colombia. While the ELN has urban cells, its areas of operations are mainly based in rural areas with weak governance.

Territories held by the ELN’s different fronts. Source: Fundación Paz & Reconciliación

Consequently, the ELN’s need for making consensus between autonomous factions have impeded previous negotiations with the government. Dissenting factions within the ELN have also used violence to undermine negotiations in the past. Talks between the ELN and the government earlier in 2016 nearly came to a halt as a result of attacks by the Domingo Laín Front, the ELN’s strongest front with 500-1,500 militants under its command. The leader of the Domingo Laín Front and newest commander in the COCE, Gustavo Aníbal Giraldo Quinchía (aka “Pablito”), is considered to be more hardline than other ELN leaders.

Unlike with FARC, there is currently no ceasefire between the ELN and the Colombian government. The Colombian government has continued to crack down on the ELN’s financial activities as a result. On October 17, the Colombian army arrested four ELN militants and killed one. Two ELN militants, including Luis Cortez, Pablito’s second in command in the Domingo Laín Front, were arrested in Venezuela for drug trafficking two days later. While the Colombian government’s continued crackdowns may help further weaken the ELN and give it the upper hand in the upcoming negotiations, it could also cause the ELN to renege its promise to release more hostages, retaliate violently, or reject the peace talks.

Assuming that peace talks with the ELN do succeed, there are still many concerns that will have addressed in post-conflict Colombia. Former ELN & FARC militants may turn to crime after the peace process, as seen when many ex-paramilitaries formed criminal organizations (known as “Bacrim,” short for “Bandas Criminales”). Bacrim groups and cartels will try to take over the ELN’s and FARC’s territories and illegal financing activities once the guerrillas disarm. The possibility for ELN splinter groups to form and continue fighting is especially high given its decentralized structure and internal factions. Peace in Colombia may also have spillover effects on Venezuela’s crisis; ex-militants may choose to fight in Venezuela where they already have operations set up, and the ELN & FARC’s old weapons on the black market may further help fuel conflict.