Mexico's Guerra al Narco: A Disaster Rooted in Misinterpretations

Activists of the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity during a protestation against Calderón in Mexico City (February 24, 2011). Via Flickr Creative Commons

With the recent disappearance of 43 students in the Mexican city of Iguala, that highlighted once more the country’s profound issues with corruption and drug cartels, three questions require answers: Why did Mexico’s Guerra al Narco fail? What are the reasons? What is the extent of this failure?

Shortly after taking office on the 1st of December 2006, Felipe Calderón declared the War on Drugs. His words were soon met with direct actions as the army and federal forces moved into Nuevo León, Guerrero, Michoacán, and Tijuana. Even though it was not the “first time Mexico has brought out the military to quell drug-related violence” (O’Neil 2009: 69), Calderón’s stance certainly exceeded previous militarized operations in both rhetoric and scale. In regards to the former, words like war, fight or security were constantly used by Calderón’s administration. The latter is exemplified by the deployment of more than 50,000 soldiers and federal troops in the streets of Mexico by 2012 (Watt and Zepeda 2012).

Whilst most analysis places this surge of armed forces as an end of Calderón’s strategy rather than a mean, it is essential to recognize that “the goal of this military intensive approach […] is to use the military to directly combat and dismantle drug trafficking organizations so that the government has time to establish an array of institutional reforms” (Weeks 2011: 17). As such, Calderón’s approach had a tripartite structure: re-establish security in the areas most affected by drug cartels, fight corruption in municipal and federal polices, and reform the judicial system.

Eight years after his election, most scholars agree that “Calderón took the wrong approach to the war on drugs” (Flannery 2013: 1). Rather than providing security to Mexican people, Calderón’s Guerra al narco led to a sharp increase in violence: the number of homicides nearly tripled over Calderón’s term from 10, 452 in 2006 to 27, 213 in 2011 (Flannery 2013). The picture gets even worst when one acknowledges the fact that crime reached places like Aguascalientes which were previously “immune to the violence that was raging in cities along the U.S.-Mexico border and elsewhere in the country” (Kellner and Pipitone 2010: 29). When such facts are put against the words (see BBC documentary below, 27:59-28:15) of the Secretary for Public Security under Calderón, Genaro García Luna, to BBC reporter Katya Adler, one can safely conclude that Calderón’s War on Drugs failed to reduce violence and provide security to the Mexican people.

This however represents only one side of Calderón’s failure. As outlined earlier, Calderón’s War aimed also at fighting corruption and strengthening the judiciary. These two components of Calderón’s strategy have been much less discussed and the first part of this article will illustrate the government’s failure in these areas. Within this section, the negative side effects that resulted directly from Calderón’s approach will be also assessed: psychological effects on Mexican people, militarization of the state and regional strengthening of drug-trafficking organizations. The first segment of this article argues that Calderón’s War on Drugs was not just a failure, it was a total disaster. Not only did the government failed to achieve its top priorities, but Mexico’s Drug War had spillover effects which now threaten the future of Mexico’s youth and democracy as well as Latin America overall.

The second part of this article looks at the reasons behind this disaster: the Calderón administration’s misinterpretations of the problem. Its understandings of cartel’s organization and of the Mexican security apparatus were far from the realities. Constructed around misconceptions, Calderón’s War was doomed to worsen the situation. Such arguments thus advocate for more research on drug-trafficking organizations, and Mexican’s judicial and security structures. With a better understanding of the situation, the Mexican government will be able to articulate strategies which will target the roots of the problem.

Mexico’s Failed War on Drugs: The Story of a Tragedy

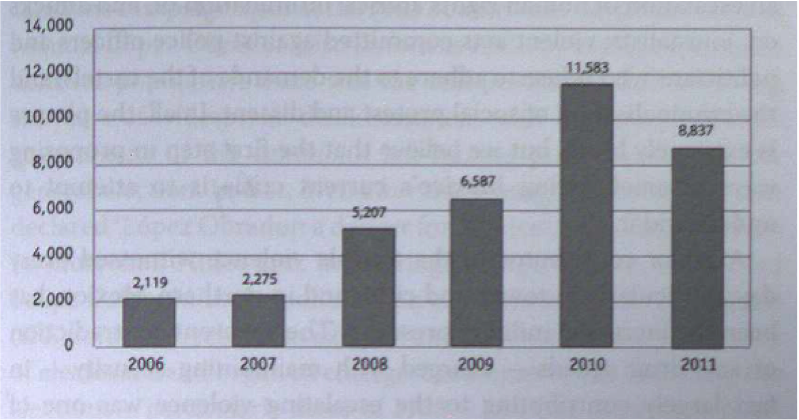

According to Figure 1, the number of homicides related to narcotrafficking increased fivefold between 2006 and 2010. Even though all scholars have confirmed the surge in violence in the aftermath of Calderón’s election, it remains essential to provide an assessment of his failure to achieve its first priority: lower violence. This failure is outlined not only by the increase in violence in the states where the federal police and the army moved in, but also in the spreading of crime to initially peaceful areas. Jose Merino provides a good account of both trends when he states that “homicides in those states [where federal police and army engaged with local forces in joint operations] increased by 12,000 between 2007 and 2010” (Poiré 2011: 26) and that “the number of Mexicans living in a municipality with homicide rates above 50 per 100,000 people moved from 850,000 in 2007 to 9.1 million in 2009” (Poiré 2011: 26). These alarming numbers clearly indicate that Calderón’s military response did not achieve the desired outcome.

Figure 1: Number of homicides related to narcotrafficking in Mexico, 2006-2011

Furthermore, the increase in violence also finds its root in the performance of the security forces. As a 2011 Human Rights Watch report indicates, the public security policy “has resulted in a dramatic increase in grave human right violations” (Human Rights Watch 2011: 5). In the five states analyzed by Human Rights Watch (Baja California, Chihuahua, Guerrero, Nuevo León, and Tabasco), 170 cases of torture, 39 “disappearances” involving security forces and 24 extrajudicial killings were reported (Human Rights Watch 2011). Rather than isolated acts of violence, the report states that “they are examples of abusive practices endemic to the current public security strategy” (Human Rights Watch 2011: 5). Hence, there is strong evidence that attests to the failure of Calderón’s militarized answer in increasing public security. Rather, it exacerbated a climate of violence in which the drug-trafficking organizations and the security forces were the main actors. Most scholars have denounced the failure of Calderón’s approach solely on the ground of the increase in crime. It is however necessary to assess the results of the two other components of his strategy: reducing corruption and strengthening the rule of law.

The heart of Calderón’s strategy was the military. Perceived as the less corrupted element of the security forces, sending the army was a way to buy time in order to reorganize Mexico’s federal and municipal police forces. The simple line of this policy was to replace corrupted police officers by professional and reliable agents as well as to reinforce the 2,200 municipal police departments (Longmire 2011). However, Mexican Intelligence’s estimation indicates that by 2008 62 percent of the police forces were either linked or took part in narcotrafficking activities and 57 percent of the police’s weaponry was used in illegal activities (Castillo García 2008). This unofficial source was backed up by a 2008 United Nations report which stated that between 50 to 60 percent of municipal security offices were incorporated into the drug cartel’s feudal scheme (Watt and Zepeda 2012). This occurred despite Calderón’s attempts to fight corruption through both an increase in the basic security officer’s salary by 46 percent (Watt and Zepeda 2012) and the dismissal of 10 percent of the federal police force by August 2010 (Longmire 2011). This video, from June 2012, shows a joint Mexican police-drug cartel kidnapping: the police officers leave the building with three handcuffed men (in white and wearing underwear) who according to CBS News were found dead hours later.

Despite its apparent immunity to corruption based on “the loyalty of the military to the nation and troops’ disciplined obedience to a higher chain of command” (Weeks 2011: 34), the military faced a greater level of corruption among its ranks as its involvement in counter-drug operations increased. And indeed, “reports of cooperation and mutual support between the military and narcotrafficking organisations have become more common, with the army at times opting not to destroy plantations of poppies and marijuana, or working actively for narcotraffickers by protecting these crops” (Watt and Zepeda 2012: 203). Finally, the most accurate indicator that points out to Calderón’s failure to rollback corruption in the security apparatus is people’s perception. Using the Delphi panel’s score on the Defense Sector Assessment Rating Tool (DSART), a study (Paul, Schaefer, and Clarke 2011) shows that the security forces’ capability to control corruption was perceived as very weak by the participants. It scored only 1.27 (the average score across all capabilities being 2.10) and a participant believed that “corruption in the forces of order is the single biggest barrier to effectively opposing the DTOs [Drug-Trafficking Organizations]” (Paul, Schaefer, and Clarke 2011: 73). Hence, Calderón’s tough policy did not manage either to reduce corruption in the police forces or to prevent the infiltration of the army by drug cartels.

In the years following his election, president Calderón outlined several proposals for judicial and legal reforms to the Congress. Two major improvements were the approval of both a single national system of police development in the General Law of the National System of Public Security until the end of 2008 and the confiscation of goods used in a criminal activity in the Federal Law of Forfeiture in 2009, as well as a judicial reform approved in March 2008 which replaced secret written trials by oral ones (Chabat 2010). Moreover, “Calderón’s reforms also modernized and strengthened the judiciary by altering investigation approaches and creating new criminal codes for organized crime” (Weeks 2011: 44).

Behind these apparent successes lies in fact a great failure. Firstly, approval by Congress does not entail direct implementation. By 2011, the judicial reform for oral trial accepted by the Congress in 2008 was not in place (Poiré 2011). Secondly, despite the changes in both the judiciary and legal systems, “fewer than 25 percent of all crimes are reported in Mexico, and of those, fewer than 2 percent are successfully prosecuted, due to system’s inefficiency and lack of transparency” (Longmire 2011: 120). Thirdly, even the security forces do not abide to the rule of law. Most of the human right violations are sent to the military justice where impunity is a widespread practice. In the five states analyzed by the Human Rights Watch report, less than one half of one percent of the 3, 671 military investigations have been prosecuted between 2007 and 2011 (Human Rights Watch 2011). Thus, despite the apparent changes in legal and judicial systems, both drug-trafficking crimes and human right violations committed by security officers remain unpunished.

At the end of Calderón’s presidency, all indicators support the failure of his administration to achieve its top priorities: reducing violence linked to drug-trafficking activities, ending corruption rooted in security forces, and reforming the judiciary and the legal frameworks. However, the story of Mexico’s Drug War’s tragedy does not end there. Indeed, this strategy led to three negative by-products. The first one relates to the militarization of the Mexican state. Jose Merino is right when he states that “the battle against narcotic traffickers has undermined exactly what is needed to win this war: the rule of law” (Poiré 2001: 25). And indeed, since the start of the War on Drugs in 2006 and the deployment of 45,000 troops in the streets of Mexico, the army has replaced the federal and municipal police forces in the delivering of public security. Furthermore, there was an increasing trend in the number of military personnel appointed to government leadership positions during Calderón’s presidency. Since 2000, “the number of active-duty military commanders holding civilian leadership positions has nearly doubled from 4, 504 military officers to 8, 274 in 2008” (Weeks 2011: 30). What do these two trends entail for Mexican’s democratization? The growing participation of the military in the War on Drugs presents a direct threat to the consolidation of Mexican democracy. Indeed, “military-based counter-narcotics policy has the formidable potential to undermine civilian control over the armed forces, weaken democratic institutions, and subvert democratic practices in Mexico” (Weeks 2011: 40).

Another side effect of Calderón’s militarized solution is the psychological impacts of violence on the Mexican population. A recent study analyses the effects of the War on Drugs on forty students attending the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. It concludes “that exposure to traumatic events in Ciudad Juárez has produced, and continues to cause, significant negative mental health outcomes in young people” (O’Connor, Vizcaino, and Benavides 2013: 7). The data gathered from the forty participants present high levels of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (32.5%), depression (35%), and anxiety (37.5%); all of which were the outcomes of facing events related to the War on Drugs like being in an armed conflict or witnessing a killing or dead body (O’Connor, Vizcaino, and Benavides 2013). Such findings are also present in the 2011 Human Rights Watch report which looks at the psychological effects of human rights violations committed by security forces. The stories of a victim of waterboarding and of the brother of a man who was executed by Navy officers both point out to the trauma caused by these events. Whilst the former could not take a shower as the water reminded him of his torture, the latter was grasped by fear each time he saw a military convoy (Human Rights Watch 2011). The War on Drugs thus leads to traumatic disorders that could have negative impacts on the psychological well-being of a large portion of the Mexican population and of the Mexican youth over the long-term.

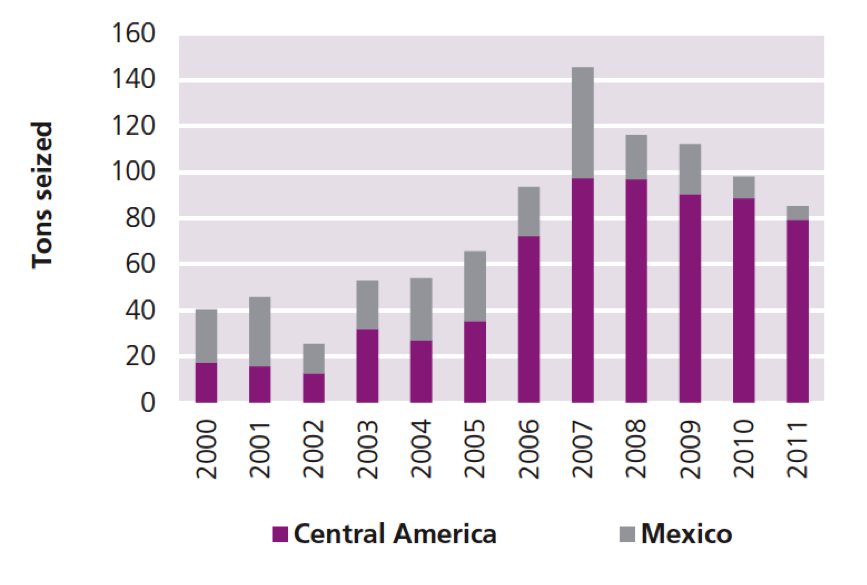

A final by-product of the Guerra al narco is the diffusion of drug-trafficking activities to the south of the Mexican state. As Figure 2 shows, the proportion of cocaine seized in Central America is increasing in comparison to the quantity apprehended in Mexico since 2005. Whereas total cocaine seizures were split equally between Mexico and Central America in 2005, the share of cocaine seized in Central America represented about 95% of the total cocaine seized in both regions in 2011. This is direct outcome of Calderón’s strategy. According to the 2012 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime report, “after 2006, the year the Mexican government implemented its new national security strategy, it became more hazardous for traffickers to ship the drug directly to Mexico, and so an increasing share of the flow began to transit the landmass of Central America” (UNODC 2012: 11). Edward Fox presents this phenomenon as the “cockroach effect”: when criminals are under the spotlights, they simply change locations (Fox 2012). Two large Mexican drug-trafficking organizations, the Zetas and the Sinaloa Cartel, had a strong presence in Guatemala by 2012 and reports have indicated their movements to Honduras (Fox 2012). Hence, Calderón’s war has opened new market channels for the Mexican cartels which could in turn undermine the stability of Central American countries.

Figure 2: Cocaine seizures in Central America and Mexico, 2000-2011

Presenting Calderón’s failure simply by looking at the sharp increase in violence grasps only one side of the disastrous effects of his approach. Not only did his militarized response failed to ensure public security, but it also did not manage either to revert corruption or reform Mexican’s judicial and legal systems. On top of that, the Guerra al narco had three negative side effects. Whereas the militarization of the Mexican state is a direct threat to its democratization, the psychological effects of the War on Drugs on the Mexican population could lead to a “lost generation”. Last but not least, the crackdown on drug-trafficking organizations forced them to seek new channels south of the Mexican border. Their activities in Central America could further undermine the stability of countries like Guatemala and Honduras. Hence, what appeared to be at first a failed strategy has now turned into a total disaster for both Mexico and the region as a whole. Why was Calderón’s approach doomed to aggravate an already somber situation?

A Policy Based on Misinterpretations

After declaring war to the drug-trafficking organizations, Calderón sent the army and the federal force to the areas where the drug cartels were well established. He decided to confront them at the heart of their networks, targeting both the leaders and the products (i.e. crops), in order to destabilize their organizations and their trade patterns. Alejandro Poiré, Mexican government’s spokesman for security affairs in 2011, outlines the successes of this policy: since 2006, 21 of the 37 most-wanted leaders of major drug-trafficking organizations have been killed and Mexican security forces have seized more than 9,500 tons of drugs and over 122,000 weapons (Poiré 2011). This does not match the arguments outlined in the previous section, which point out to the disaster of this strategy. The confidence of government officials in the achievements of the War on Drugs is a clear indicator of their total misunderstanding of the problem. Calderón’s approach was rooted in the misinterpretations of both the drug-trafficking system and the security forces’ capabilities.

In regards to the former, Calderón’s policy assumed that disturbing the trade system and the leadership of drug cartels would reduce violence by limiting the cartels’ access to funds and disrupting their hierarchies. This however illustrates a total misreading of drug-trafficking organizations’ structure. In his recent TED talk, Rodrigo Canales argues that Mexican drug cartels present the same organizational patterns as any other formal businesses (TED talk The deadly genius of drug cartels 2013, see below). In other words, attacking the trade routes of these organizations entails a direct threat to their main economic activities. Whereas formal corporations would use the legal tools available to them to maintain their competiveness, the criminal organizations resort to violence as it cannot pretend to legal means. “He [El Chapo, leader of the Sinaloa Cartel] wants the bridge to send goods to the Gringos. That is the fight in case you don’t know,” stated a former hit man for the Juárez Cartel to BBC reporter Katya Adler (see BBC documentary, 49:07-49:20). To secure trade routes, Mexican drug cartels enter into full-armed confrontations with the state. Hence, Calderón’s strategy of targeting trade networks was doomed to increase violence.

Furthermore, the Mexican government failed to acknowledge the deep connections that Mexican drug-trafficking organizations had built with local population and regional criminals. Canales gives a striking example of this: it relates to the events that occurred in the city of Apatzingán (Michoacán state) in December 2010 (TED talk The deadly genius of drug cartels 2013). Following a two days confrontation between federal forces and a local criminal organization, the Michoacán family, the mayor of this city decided to set up a march for peace. The day of the procession, half of the participants were holding banners and signs in support of the criminal organization. This behavior highlights the simple fact that the Michoacán family had engaged local civil societies well before the federal and police forces. For Canales, this example “is a perfect metaphor for what’s happening in Mexico today, where we see that our current understanding of drug violence and what leads to it is probably at the very least incomplete” (TED talk The deadly genius of drug cartels 2013).

On another level, the government’s strategy of targeting the leadership of drug-trafficking organizations was a catalyst for the surge in inter-cartels violence. Rather than decreasing the number of Mexican cartels, the killing of cartel’s leaders disrupted the equilibrium patterns to which drug-trafficking organizations had previously agreed and opened space for the creation of new criminal organizations. “According to a study presented by Mexican security analyst Eduardo Guerrero (Nexos, June 2011) the number of cartels in Mexico climbed from six to 12 between 2007 and 2010, while the number of smaller local organizations increased from five to 62 in the same period” (Poiré 2011: 27). With this trend, competition to secure trade routes skyrocketed between the old drug cartels and the newcomers. Violence being the mean by which the drug-trafficking organizations secure their markets, it is not surprising that the increased in competition following the entering of new groups led to a surge in inter-cartel violence.

Whilst disrupting the trade patterns boosts the ferocity of drug cartels, it fails to target the roots of their financial profits: money laundering. And indeed, “the government crackdown on organised crime would be more effective in combating the power of Mexican drug traffickers were it to target the banks responsible for housing their profits” (Watt and Zepeda 2012: 210). Large financial groups like Banco Santander, Wachovia, Bank of America, Citigroup, American Express, Western Union and HSBC were all presumed to take parts in laundering activities on behalf of the Mexican drug cartels and were being investigated by the US Drug Enforcement Agency in 2010 (Watt and Zepeda 2012).

Calderón also overestimated the capabilities of the Mexican security forces to fight the drug cartels. Looking at the structure of the Mexican army, “the purpose of which is not to be a fighting army, but to participate in rescue efforts when some natural disaster strikes the country” (Castañeda 2010: 2), Jorge Castañeda (former foreign minister of Mexico during Vicente’s term) argues that the Mexican army is “totally unprepared to fight a war against drug cartels” (Castañeda 2012: 2). As shown previously, the apparent immunity of the Mexican military to corruption has been shattered as the increasing involvement of the army in drug-trafficking operations led to greater corruption within its ranks.

Calderón’s strategy also aimed at strengthening both the municipal and the federal police forces. His reforms however failed to recognize the penetration of the drug-trafficking organizations in these two security structures on one hand and their deplorable conditions on the other hand. In regards to the former, by December 2010 less than 50 percent of state police officers had took a Trust test in 29 of Mexico’s 32 states and as many as 65 percent of the ones who were subjected to it did not succeed (Poiré 2011). Furthermore, both the low wage earned by the police officers and the high risks that non-cooperation with drug cartels entail are incentives that force many “clean” municipal and federal police members to embrace corruption. One ex-sicario (assassin working for a Mexican drug cartel) “claims that, at the end of his training in the police academy, at least fifty of his 200 companions joined criminal organisations after graduation” (Watt and Zepeda 2012: 203).

Moreover, the lack of education, poor equipment and poor physical conditions among municipal and federal police forces make them inefficient against drug-trafficking organizations, which are equipped with modern lethal weapons. The magazine Wired provides examples of the cartels’ weaponry. Recent reports indicate that “forty-three percent of local cops are too old to effectively perform their basic duties, and 70 percent are considered overweight to obese – which translates into an inability to chase a suspect for more than 300 feet. Many officers still use old .38-caliber revolvers – obsolete for over a decade and seriously outmatched by AK-47s and .50-caliber rifles used by narcos” (Longmire 2011: 118). Hence, whilst the military is not tasked to wage a war on drug-trafficking organizations, the federal and municipal police forces do not have the power to ensure public security and chase drug criminals. Reforms should thus target these structural issues and focus on training rather than simply focusing on the purge of the old system and its replacement with new, undertrained, and unskilled police officers.

The judicial system’s aim is to prosecute the drug criminals once they are captured by the police forces or the military. If Calderón overestimated the capabilities of the security forces to kill or arrest members of drug-trafficking organizations, he also misjudged the judiciary’s abilities to pursue cases in courts. Despite the multiple reforms he implemented to modernize investigation techniques and facilitate trials, the average impunity index in Mexico was around 98 percent in 2009 (Weeks 2011). Moreover, the reforms have also increased the stages in the judicial structure that drug cartels can corrupt or intimidate. “This is because changes, such as greater dependence on evidence, greater involvement of judges, the creation of new justice positions, increased participation of defense attorneys, and expanded procedural measures in Mexico’s 2008 reforms create greater bureaucracy and regulation in the judicial system” (Weeks 2011: 50). Finally, the time lag between capture and prosecution can take months or years: accused drug criminals waiting for the final judicial decision represent currently nearly 40 percent of the people held in the Mexican prisons (Weeks 2011). To add on these deficiencies, the Mexican judicial system is not even capable of dealing with human right violations committed by security forces. “Justice officials fail to take basic steps such as conducting ballistic tests or questioning the soldiers and police involved” (Human Rights Watch 2011: 9) when investigating extrajudicial killings.

In other words, Calderón’s War on Drugs was based on a total miscomprehension of the capabilities and the structures of the two main actors involved in this security issue: the drug-trafficking organizations and the Mexican security apparatus. It thus seems natural that his strategy was not only doomed to fail, but was also fated to worsen a problem which has haunted Mexico for decades. Rather, Calderón should have followed a more bottom-up tactic: emphasize the structural and operational reforms of both the security forces and the judicial system. The top-down line he undertook, with the deployment of military and federal police forces in the streets of Mexico, did not target the roots of the problem: corruption in all governmental and security branches, the financial source of drug cartels and the drug market itself.

Conclusion

As of today, it appears that the Mexican drug cartels have the upper hand in Mexico’s Drug War. Rather than solving the security problems related to drug-trafficking activities, Calderón’s strategy exacerbated them. The War on Drugs he undertook at the beginning of his term was a total disaster. Firstly, Calderón’s approach failed to accomplish the three top priorities on his agenda: ensure public security, reinforce Mexican security structures, and reform both the legal and judicial systems. Secondly, it actually aggravated the situation. Violence skyrocketed over his term. Corruption became endemic in the army and the police forces. All of this occurred despite his attempts to root out drug cartels’ penetration of the security forces, reform the judiciary, and disturb the drug-trafficking organizations’ structure and trade patterns. Finally, Calderón’s War led to three unexpected by-products whose potential negative effects could worsen even further the initial disaster. The militarization of the Mexican state, the psychological impacts of Mexico’s Drug War on the Mexican population, and the movement of drug cartels into Central America could respectively endangers Mexican democratization, produces a “lost generation”, and threatens the stability of the region as a whole. Why did Calderón’s approach failed?

His policies were based on a deep misunderstanding of both actors involved in the drug issue: the drug-trafficking organizations and the Mexican security forces. In regards to the former, Calderón’s strategy perceived drug cartels as criminal organizations. It thus failed to see that they in fact behave like any other formal business with only one difference: as drug cartels cannot pretend to legal means to ensure their competiveness, they resort to violence. By opening channels for new comers and threatening drug cartels’ trade routes, Calderón’s response led to a surge in both inter-cartel violence and cartel-state confrontations. Focusing on the products, his approach did not target the source of cartel’s revenue: money laundering. Finally, Calderón overemphasized the Mexican security and judiciary’s capabilities to fight drug-trafficking organizations. Corruption is deeply rooted in both the military and the police structures. Furthermore, whereas the former is not tasked to fight drug cartels, the latter is ill-equipped and poorly trained. Despite reforms, the Mexican judiciary still fails to prosecute both drug cartel criminals and human rights violation committed by security forces. Within this body, corruption is also well established but the main handicap is the simple fact that most justice officials fail to perform the most basic stages in investigation procedures, such as questioning witnesses.

Thus, this article advocates the need to increase in-depth research on the security structures and the cartel organizational behaviours. With this in mind, the Mexican government will have a much more accurate picture of the situation and will be equipped to target the roots of the drug-related issues. As Calderón’s approach illustrate, misinterpretations can be fatal. Sadly, the Iguala case indicates that his successor, Enrique Peña Nieto, did not learn the lessons. The political momentum and the public visibility that this affair gained in Mexico are nonetheless signs of hope: the Mexican people are tired of their government failures and the continuing violences. They are not afraid anymore to manifest in the streets to ensure greater accountability from the part of the Mexican state as well as ask for more positive results. This is one small step towards change…

REFERENCES

- Adler, Katya (2010) Mexico’s Drug War, BBC World Service.

- Canales, Rodrigo (2013) The deadly genius of drug cartels, TED Talk, New York: TEDSalon 2013.

- Casteñada, Jorge (2010) “Mexico’s Failed Drug War,” Cato Institute Economic Development Bulletin, No. 13.

- Castillo García, (2008) “El narco ha feudalizado 60% de los municipios, alerta ONU,” La Jordana, 26 June.

- Chabat, Jorge (2010) “Combatting Drugs in Mexico under Calderon: The Inevitable War,” Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, No. 205.

- Flannery, Nathaniel Parish (2013) “The Rise of Latin America: Calderón’s War,” Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 66, No. 2, 181.

- Fox, Edward (2012) “UN Report Highlights Regional Consequences of Mexico’s Drug War,” InSight Crime: Organized Crime in the Americas. Accessed on November 29th Available at URL: < http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/un-report-regional-consequences-mexicos-drug-war>.

- Human Rights Watch (2011) Neither Rights Nor Security: Killings, Tortures, and Disappearances in Mexico’s “War on Drugs”, New York: Human Rights Watch.

- Kellner, Tomas and Pipitone, Francesco (2010) “Inside Mexico’s Drug War,” World Policy Journal, Vol. 27, No. 1, 29-37.

- Longmire, Sylvia (2011) Cartel: The Coming Invasion of Mexico’s Drug Wars, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- O’Connor, Kathleen and Vizcaino, Maricarmen and Benavides, A. Nora (2013), “Mental Health Outcomes of Mexico’s Drug War in Ciudad Juárez: A Pilot Study Among University Students,” Traumatology, 1-9.

- O’Neil, Shannon (2009) “The Real War in Mexico: How Democracy Can Defeat the Drug Cartels,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 88, No.4, 63-77.

- Paul, Christopher and Schaefer, Agnes Gereben and Colin, P. Clarke (2011) The Challenge of Violent Drug-Trafficking Organizations: An Assessment of Mexican Security Based on Existing RAND Research on Urban Unrest, Insurgency, and Defense-Sector Reform, Pittsburgh: Rand National Defense Research Institute.

- Poiré, Alejandro (2011) “Can Mexico win the war against drugs?,” Americas Quqrterly, Vol. 5, Issue 4, 24-27.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2012), Transnational Organized Crime in Central America and the Caribbean: A Threat Assessment.

- Watt, Peter and Zepeda, Roberto (2012) Drug War Mexico: Politics, Neoliberalism and Violence in the New Narcoeconomy, New York: Zed Books.

- Weeks, Katrina M. (2011) “The Drug War in Mexico: Consequences for Mexico’s Nascent Democracy,” CMC Senior Theses. Paper 143.