France Targeted ‘Terrorists’ with a US-Made Bomb in Mali. Witnesses Say They Hit a Wedding

On January 3, 2021 two French Mirage 2000D fighter jets carried out an airstrike near the central Malian village of Bounti.

According to local activists and a report by the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission to Mali (MINUSMA), the strike hit a wedding party. Twenty-two people were killed, including 19 civilians. Most of the dead were men over the age of 40.

Although the MINUSMA report stated that five individuals in the wedding party of 100 were likely members of the armed Islamist group, Katiba Serma, its investigators were unable to find “any material element at the scene that attested to the presence of weapons.”

Despite this, France’s Minister of Armed Forces, Florence Parly, dismissed the report’s findings, claiming at a press conference during an official visit to Bamako in April 2021 that the men targeted in the airstrike were terrorists and that “all the fundamental principles aimed at preserving civilians have been applied”.

MINUSMA’s findings regarding the French airstrikes in Bounti are now available to read in full. #Mali @UN_MINUSMA concludes:

-16 of the 19 people immediately killed by the airstrikes were civilians

– There was a wedding in Bounti the day of the incidenthttps://t.co/abOU8UPg3A— Seán Smith (@SeDanSmith) March 30, 2021

While French forces carried out the Bounti operation, which was undertaken as part of the Operation Barkhane anti-insurgency mission, the weapon used appears to have been American-made.

The MINUSMA report included pictures of the shrapnel from the bombs used in the airstrike, allowing open source researchers to identify the weapon used as a GBU-12 Paveway II laser-guided bomb manufactured by the US-company Raytheon.

As previously reported by Bellingcat, the same type of ammunition was used in a Saudi strike that hit a wedding in Yemen in 2018. In that instance 33 people, mostly women and children, were killed. A GBU-12 Paveway was also reported to have hit a detention centre in the Yemeni town of Sa’adah earlier this year, killing at least 80 and injuring over 200.

A general view of a GBU-12 Paveway laser-guided bomb and a General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper drone during a visit of French Defence Minister Florence Parly to the French Air Force pilot school at the BA 709 military air base of Cognac-Chateaubernard in Chateaubernard, France May 14, 2020. Mehdi Fedouach/Pool via REUTERS

Experts who spoke to Bellingcat about the Bounti incident said they believed the fact a US-made weapon was used in such a way should attract scrutiny from the country’s legislature, which is charged with approving weapons sales and monitoring their end-use. It remains unclear if Congress was notified by the State Department (which informs Congress on such issues) in the aftermath of the strike or if it assessed that it was not required to.

Although major US media outlets, including The New York Times and The Washington Post, covered the release of the MINUSMA report, neither noted the deployment of a US-made bomb or raised wider questions about the end-use of such weapons provided to allies such as France, which has cooperated with the US in Mali and the wider Sahel region.

A US-made MQ-9 Reaper drone was also used for reconnaissance during the mission.

A spokesperson for the US State Department told Bellingcat that it did not comment on deliberations with Congress as a matter of policy when asked if it was aware of, or if it had informed the body, that a US-made weapon had been used in the Bounti airstrike. They did, however, say that all military operations must be carried out in accordance with international humanitarian law — including obligations related to the protection of civilians – while noting that the MINUSMA report concluded that three members of Katiba Serma had been killed in the strike.

No mention was made of the 19 civilian deaths documented by MINUSMA.

Questions by Bellingcat and Afrique XXI to the French Armed Forces on what happened in Bounti went substantively unanswered, with reporters directed to previous statements denying any wrongdoing.

Raytheon did not respond to requests for comment.

A Battle of Narratives

The day after the airstrike, mentions of what had happened in Bounti began to appear on social media.

The French government’s account of the event was shared in a press release on January 7. It claimed that, for more than an hour before the airstrike, an MQ-9 Reaper drone flew on an intelligence gathering mission over the Douentza region in central Mali when the drone detected a motorbike with two individuals, just north of the RN16 highway. Eventually the motorbike joined a group of about 40 other men a kilometre from Bounti.

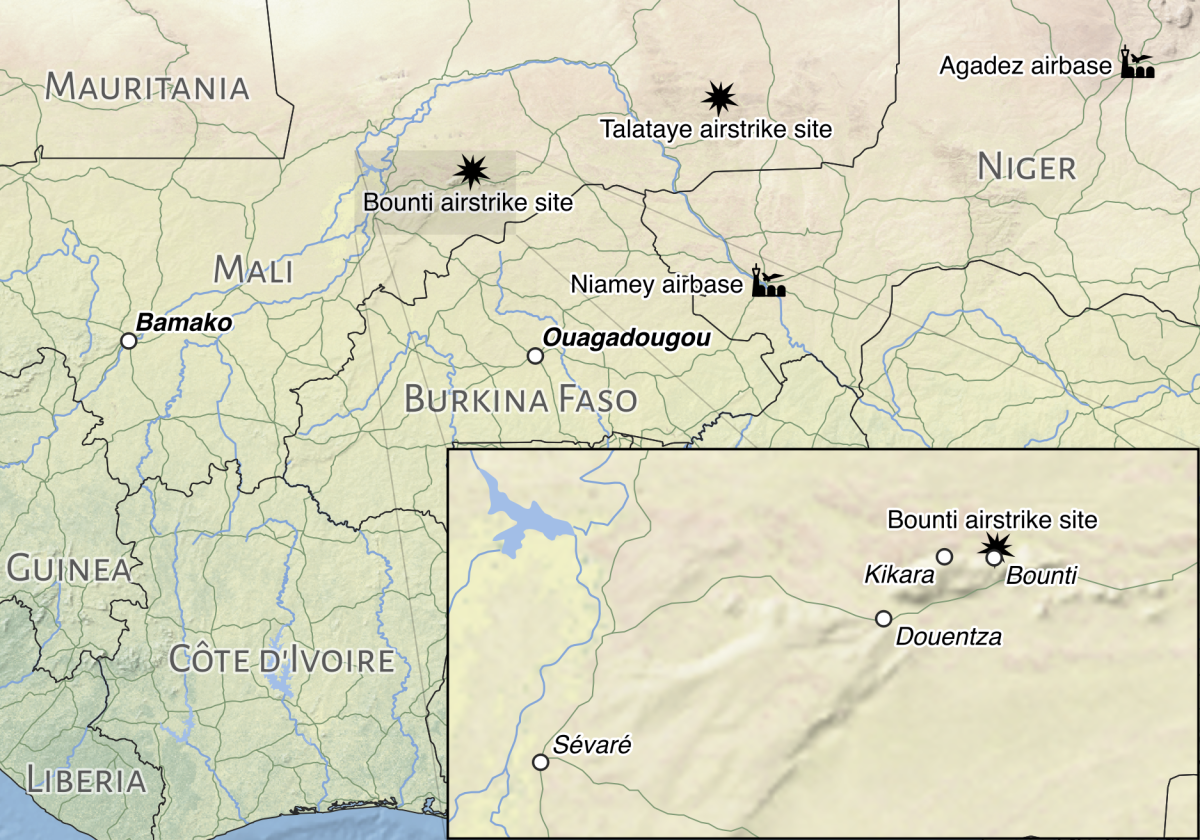

A map of the Sahel region. Credit: Logan Williams / Bellingcat / Natural Earth.

“All the intelligence and real-time elements then made it possible to characterise and formally identify this group as belonging to a GAT [Groupe Armé Terroriste – Armed Terrorist Group].”, noted the press release. After one and a half hours of observation, the French army stated it did not detect women or children and ordered a strike.

Two Mirage 2000D jets already in flight were requested to strike the location at 3pm local time. About 30 men were hit. The press release provided the military coordinates 30 PWB 4436 83140 (15.223967, -2.586948) for the location of the airstrike. Bellingcat and other open source researchers were able to confirm that a burn scar appeared at this location between January 3rd and the next available day on satellite imagery.

A GIF from Satellite imagery captured by Sentinel Hub shows a black mark appearing after the Bounti airstrike.

All parties roughly agree on the events sketched by the French Ministry of the Armed Forces: the timeline, the number of casualties, the location and the gender of the victims.

However, the UN report differs from French claims on a number of key points.

The MINUSMA investigators who compiled it said they conducted individual face-to-face interviews with over 115 people, had group conversations with 200 more, and a further 100 telephone interviews.

Their report found that the vast majority of men who were targeted were not insurgents regrouping — but had actually gathered for a wedding in Bounti.

According to the MINUSMA report, the men and women attending the wedding were separated during the celebrations “as per local traditions.”

The men assembled about a kilometre from the village in an area covered by small trees and shrubs. This is where the airstrike would hit.

MINUSMA’s interviewees suggested that five armed men they presumed belonged to Katiba Serma, a jihadist group affiliated with Al Qaeda, then joined the gathering as well. The rest of those present were civilians, they stated.

The strike hit at 3pm local time, with 19 people immediately killed on impact. An additional three died from their wounds while being transported to the nearest clinic. Among the 22 people killed, three were identified by MINUSMA as members of Katiba Serma.

“This strike raises significant concerns about compliance with the principles of military conduct”, concluded the MINUSMA report in its section on the legality of the airstrike and the identity of its targets. The report recommended an urgent, transparent and independent Malian and French investigation into the circumstances of the strike, as well as the criteria used to distinguish membership in an armed group.

Bellingcat and Afrique XXI contacted the Cabinet of the Chief of the Armed Forces of France to inquire whether they had followed these recommendations and whether their position had changed since the MINUSMA UN report was released.

France’s armed forces declined to further comment on the case, and instead referred reporters to press releases from January 7, 2021 and March 30, 2021 in which they denied any wrongdoing.

The Connecting Code

As a NATO ally, it is not surprising that France employs some US-made weaponry. By France’s own admission, a US-made MQ-9 Reaper drone operated by France contributed intelligence gathering prior to the airstrike.

But one detail that largely went unmentioned in coverage of the Bounti strike was the provenance of the bomb used.

Stoke White Investigations (SWI), a law firm led by former Bellingcat contributor Khalil Dewan, published its own report on July 25, 2021 based on open source evidence. SWI independently identified the shrapnel pictured in the MINUSMA report as belonging to a Raytheon GBU-12 Paveway II laser-guided bomb.

Long-time Bellingcat readers and those who monitor armed conflicts will already be acquainted with this particular weapon.

In April 2018, an airstrike by the Saudi-led coalition killed 33 people at a wedding in Yemen. The weapon used in that instance was also a GBU-12 Paveway II. In early 2022, the same bomb reportedly hit a detention facility in the Yemeni town of Sa’adah after another Saudi attack.

It was images shared in the MINUSMA report that allowed the Bounti weapon and its manufacturer to be identified.

Identifying the Bomb

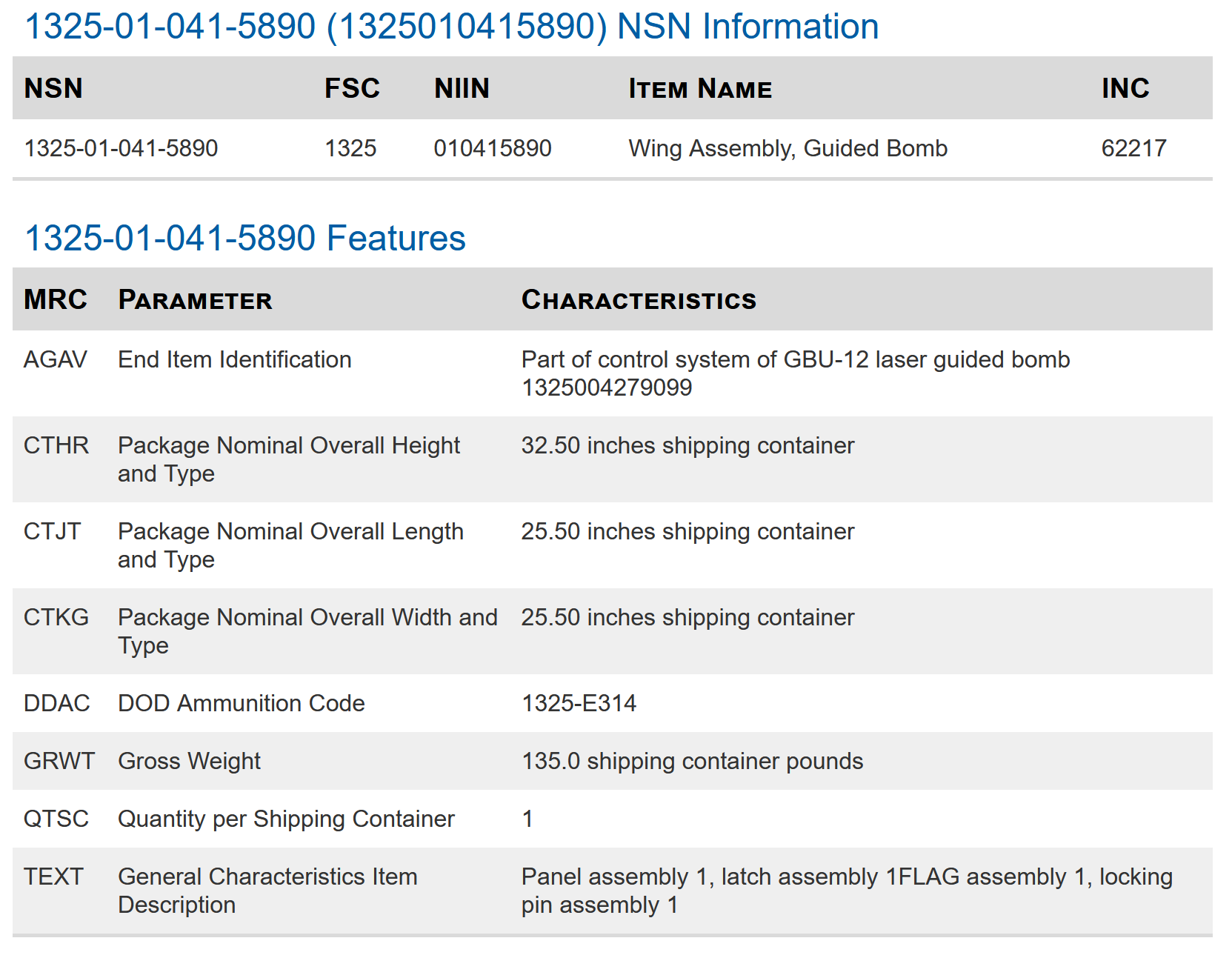

A number can be seen on the fragment. It is preceded by the letters “NSN.” This is the ‘NATO Stock Number’, a 13-digit code used by many NATO (and non-NATO) countries for identifying supplies in the NATO supply system. In the Bounti case, the full NSN (1325-01-041-5890) is visible. PartTarget, a website that details the origins of weapons components returned the information required to identify this part as belonging to the wing assembly of a GBU-12 laser-guided bomb.

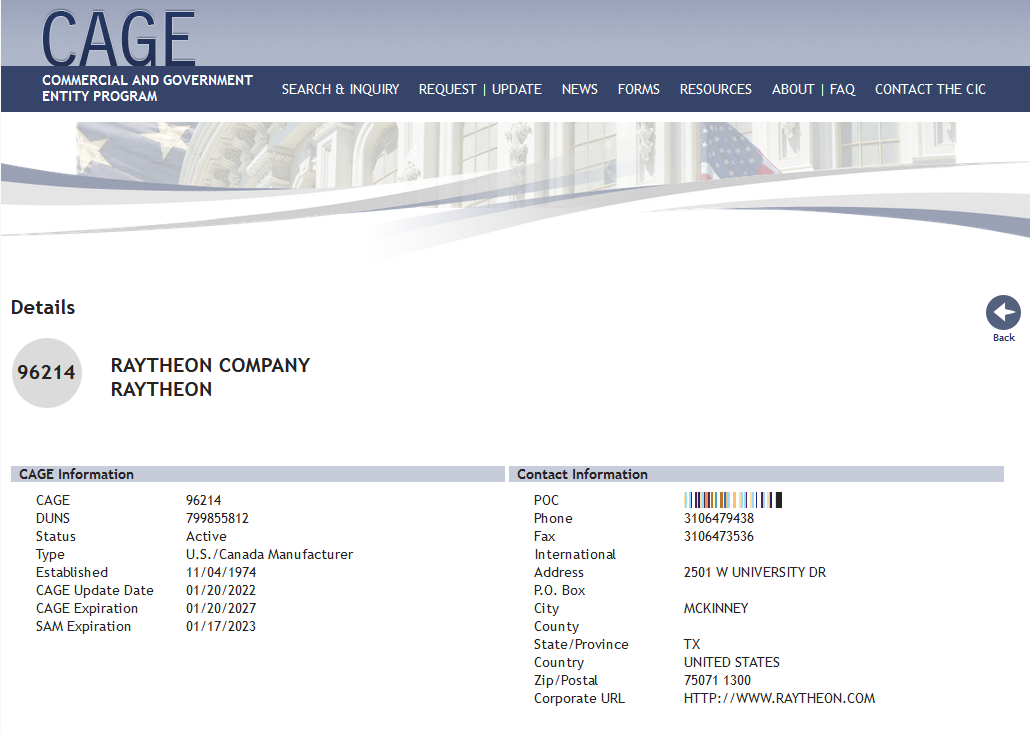

The ‘Commercial And Government Entity’ (CAGE) code 96214, marked in green in the picture, belongs to a Raytheon facility in McKinney, Texas. AGE codes can be found on the US Defense Logistics Agency website (readers may need a VPN to access it if outside the US) or with the NCAGE Code Request Tool on NATO’s website.

Finally, the technical sheet (page 6) from the French Air Force specifically mentions that the French-made Dassault Mirage 2000Ds can carry GBU-12 laser-guided bombs, the same type that was found on-site.

The United States Congress, the body that verifies arms sales through the Arms Export Control Act (AECA) of 1976, has not publicly discussed the use of US-made bombs and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) that took part in the Bounti airstrike.

While US forces in the Sahel have provided Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance (ISR) support to the French on multiple occasions, it is not known if this happened in Bounti as well.

The US and French military did not respond to questions on this subject. However, the close partnerships between the two countries and militaries is well documented. A France 24 documentary from 2020 quoted a French commander who stated that his forces in the Sahel regularly asked the US Air Force for help following potential targets, for example, when a convoy of motorbikes split.

Weapons monitors like the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute have also noted repeated sales of US equipment and weapons totaling billions of dollars to France, including the MQ-9 Reaper Drone and GBU-12 bomb used in the Bounti attack.

In June 2020, meanwhile, France’s Minister of Armed Forces, Florence Parly, said France had received information from the US that allowed them to “neutralise” Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb leader Abdelmalek Droukdel.

“Nous avons neutralisé le chef d’Al-Qaida au Maghreb Islamique, Abdelmalek Droukdel, grâce à une intervention audacieuse, mais qui n’aurait jamais pu se produire sans le renseignement que les Etats-Unis nous a fourni.” – @florence_parly (@Armees_Gouv)#DirectSénat pic.twitter.com/PJJXGet35v

— Sénat Direct (@Senat_Direct) June 18, 2020

This particular case was an example of what is known as a “personality strike”, where an individual is targeted by a drone based on their identity.

Yet this is not to be confused with the type of strike that it appears was carried out in Bounti.

Stoke White Investigations and Dr. Rebecca Mignot-Mahdavi, lecturer in international law at the University of Manchester in the UK, told Bellingcat the airstrike on January 3, 2021 appeared to be a so-called “signature strike” — a tactic that sees individuals monitored by drone and targeted if their pattern of behaviour is consistent with what is deemed as terrorist activity.

Analysts and rights groups say that signature strikes increase the chance of civilian casualties and injuries. The US itself has long used signature strikes in places like Afghanistan and Yemen, often with devastating consequences.

Congress, US Weapons Sales and End-Use Monitoring

US arms exports, whether sold directly by the government (Foreign Military Sale – FMS) or sold by a US company (Direct Commercial Sales – DCS), are subject to congressional oversight when the value surpasses a certain monetary value. These arms exports are also subject to end-user monitoring (EUM) to ensure that weapons are used for their intended purposes.

But some question the definition and application of EUM in practice.

“In general, end-use monitoring is implemented much too narrowly, with an institutional emphasis placed primarily on making sure weapons are accounted for, rather than when they might actually be misused, including against civilians,” Jeff Abramson, Senior Fellow at the Arms Control Association, told Bellingcat. “Both the executive branch and Congress should make sure any allegations of misuse, especially against civilians and civilian infrastructure, are investigated, ” he added.

Brittany Benowitz, an attorney with expertise in arms control processes and former Congressional staffer Democratic for Senator Russ Feingold, added that the AECA prohibits the sale of defence articles by the US to recipients that have misused them in the past. According to Benowitz, this is incorrectly interpreted as only covering violations of jus ad bellum, the conditions under which states may resort to war or to the use of armed force in general, not international humanitarian or human right laws.

Asked whether the killing of civilians would constitute a breach of jus ad bellum Benowitz responded that widespread and systematic attacks on the civilian population would likely “constitute an end-use violation even under the State Department’s narrow reading. Benowitz also added that if the State Department is on notice of a possible end-use violation they are required to notify Congress. If they fail to do so under such circumstances, it could be a violation of the AECA.

It is not known if the State Department notified Congress in the Bounti case or whether it decided not to do so because it did not consider the airstrike an end-use violation.

A State Department spokesperson told Bellingcat that “all military operations must be carried out in accordance with international humanitarian law, including obligations related to the protection of civilians.”

Asked whether the State Department had notified Congress of the Bounti case, the spokesperson responded that “as a matter of policy, we decline to comment publicly on internal deliberations and consultations with Congress.”

They also stated that “we take all reports of civilian casualties seriously and encourage thorough investigations of credible allegations of civilian casualties.”

Benowitz said that even in cases where the State Department decides a one-off incident does not meet an EUM “the Department still needs to explain what steps it took to make sure that it was only an isolated incident.”

Bellingcat and Afrique XXI contacted Sen. Robert Menéndez, the chairman of the Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee through his communications director, asking whether he was aware of what had happened in Bounti, but did not receive a reply.

Whether Congress was notified or not, even though the incident took place over 15 months ago, is not an insignificant point.

Although the future of Operation Barkhane is in flux, with France pulling troops out of Mali, it seems unlikely that it will cease its operations in the wider region any time soon.

France and Niger recently reached an agreement that will allow French troops to be stationed next door to Mali, where there are also two US airbases deploying armed drones. US support to France includes targeting guidance for drone strikes, and the Biden administration, meanwhile, has reportedly indicated it will continue to support France’s counter-terrorism campaign in the Sahel where a number of foreign forces are now present.

A year after the Bounti airstrike, on January 7 and January 14, 2022 the latest MQ-9 related sales to France were announced for an estimated total value of $300 and $88 million respectively.

Last week, Human Rights Watch reported that Malian soldiers and a number of Russian fighters had executed over 300 people as part of an anti-jihadist operation in the town of Moura. In December 2021, the Wagner Group — a Russian private military contractor accused of war crimes in other countries — reportedly arrived in Mali.

Russian presence adds another layer of complexity to the aims of France and the US in the region.

Developments like these raise further questions about the efficacy of oversight into arms sales, as well as yet more concern for the impact of foreign forces and their missions on the people of the Sahel.

The production of this investigation is supported by a grant from the IJ4EU fund. The International Press Institute (IPI), the European Journalism Centre (EJC) and any other partners in the IJ4EU fund are not responsible for the content published and any use made out of it.