Black Gold Burning: In Search Of South Sudan’s Oil Pollution

Since the discovery of oil in what is now known as South Sudan, bloody conflicts have been waged over control of areas rich with this “black gold.” During Sudan’s second civil war (1983-2005), the oil concession areas in the south became epicentres of conflict and massive human rights abuses. During the war, petrol companies from all over the world invested billions into the exploration and extraction of the oil. Yet absence of enforcement of environmental regulations, corruption, and lack of proper maintenance in oil infrastructure have been haunting the production since.

Academics, local communities, and civil society organisations have been flagging concerns over local oil spills for years, fearing health risks from pollution of drinking water vital for nearby villages. Preliminary research indicates heavy metal pollution from oil production, which warrants more investigation into the potential health risk from polluted ground water.

In 2018, UN Environment published the First State of the Environment and Outlook report on South Sudan, noting its wider concern about the impacts on the environment, which is killing fish and affecting biodiversity, stating that “Exploration and oil drilling activities are accompanied by chemicals, drilling muds, toxic produced water and oil spills that pollute the environment in and around oil fields. Toxic “produced water” is an inextricable part of the oil recovery process and is the largest volume waste stream associated with the oil and gas industry”.

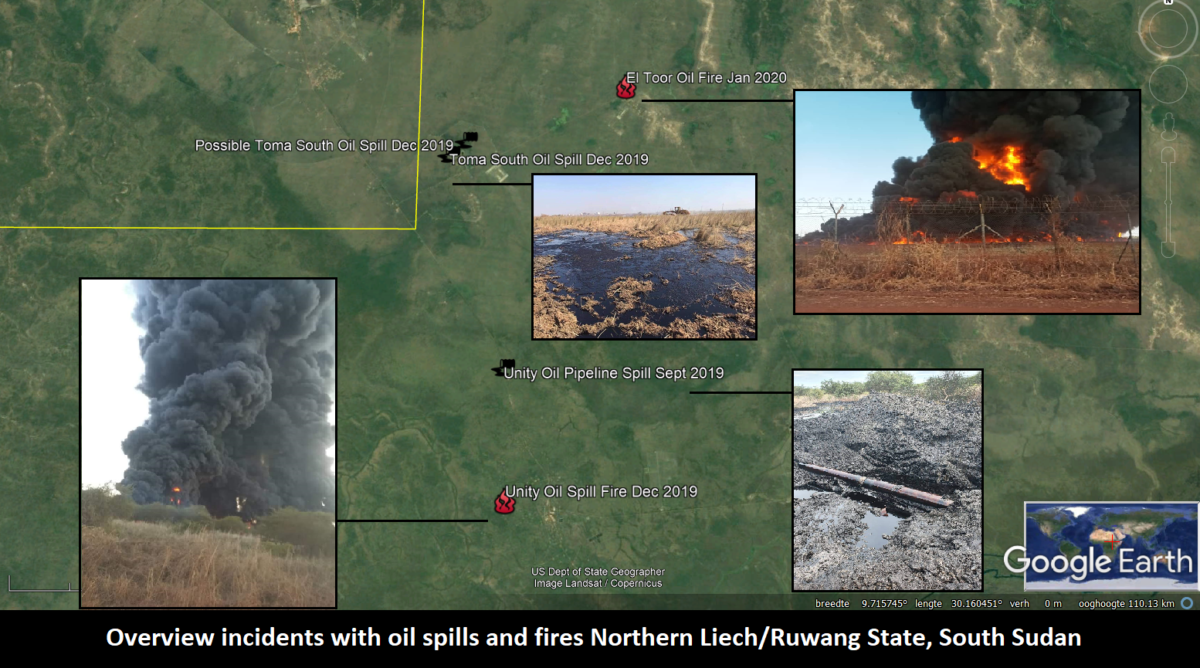

This year, multiple reports came in on oil spills from the north of the country, sounding alarm bells over the state of South Sudan’s environment and the ongoing failure by oil companies responsible to provide solutions.

This environment-focused open source investigation article is both a deep-dive into the numerous disturbing incidents and a small guide on monitoring oil spills and fires in the north of South Sudan. It aims to inspire more research into how a failing oil industry is risking poisoning the lives of local communities and the environment they depend on.

Blood, War And Petrol

The revenues collected from oil are the main source of income for the South Sudanese government. With a current annual production of 180 thousand barrels a day, petrol provides 70% of the Gross National Production, according to African Development Bank.

These valuable natural resources have been a historical source of conflict, intensifying the violence during the second civil war until 2005, with severe human rights violations linked to oil exploitation. While the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement between Sudan and the then-semi autonomous South Sudan included a section on compensation for the “oil l wars” — to be funded by the “signatories of the oil contracts” — this was never followed up on.

With gaining independence in July 2011, South Sudan soon passed strong legislation for the management of the oil industry, including high environmental standards, but the new South Sudan state proved too corrupt and embattled to follow through.

Again, during the South Sudanese civil war (2013-2018) battles were fought by different South Sudanese factions over access to the oil fields (starring some of the same protagonists, such as leaders Riek Machar and Salva Kiir). These conflicts over oil fields have been well documented by the Small Arms Survey 2015 report “ Fields of Control: Oil and (In)security in Sudan and South Sudan”.

The role of petrochemical companies, mainly coming from Asian countries such as China, Malaysia, and India, is relevant to the extent they are responsible for the maintenance of the wells, while the South Sudanese government is also accountable for the enforcement of environmental regulations, as agreed in the 2012 Petroleum Act, as called upon by South Sudanese civil society organisations with the support of the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (ECOS), and as described in an earlier article on the environmental legacy of the oil industry by this author for the Wilson Centre’s New Security Beat in 2016.

There have also been recent publications on the linkages between oil exploration and potential health effects and environmental impacts in South Sudan that warrant proper research, appropriate to the scale of the problem — as well as a push for funding clean-up and restoration efforts in order to protect human health and livelihood, as well as local ecosystems.

Seeing Spills With Satellites

Reports on oil spills coming in mid-December 2019 set us on a search to identify the areas affected, using social media and remote sensing to identify the spills — as little attention is given to this environmental problem in the media, even though international oil companies bear responsibility for the production and potential consequences.

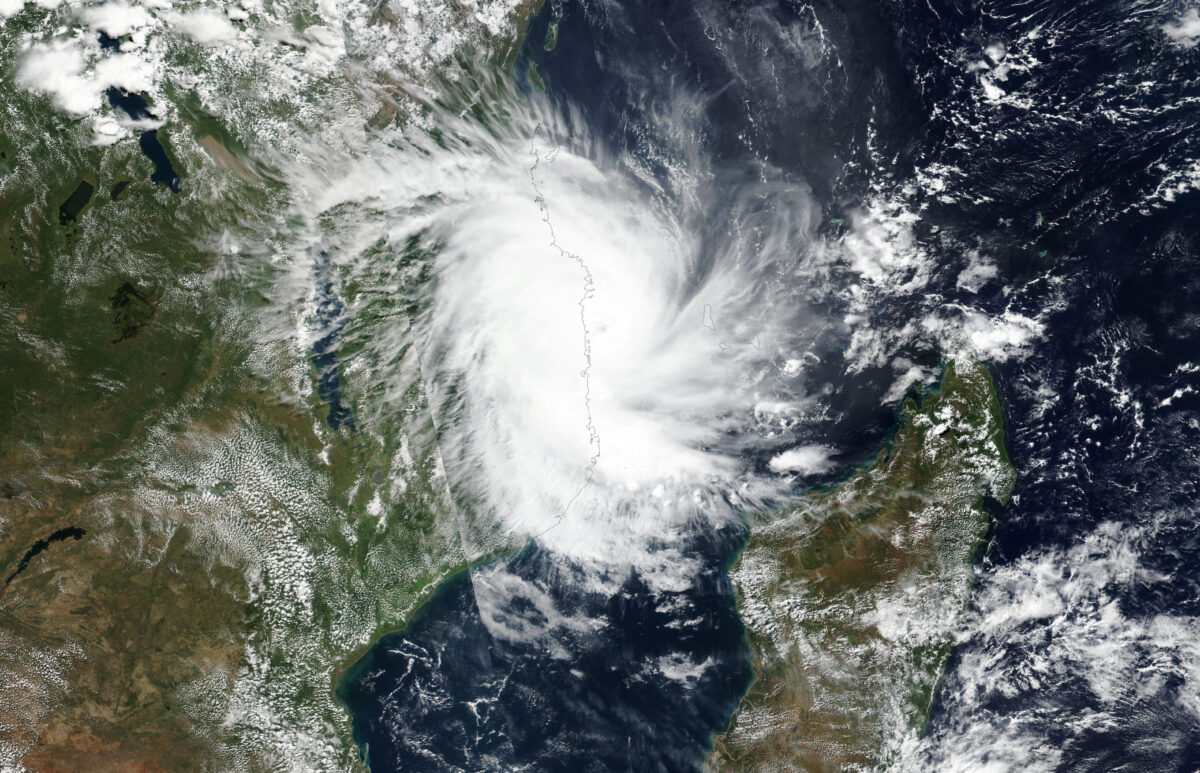

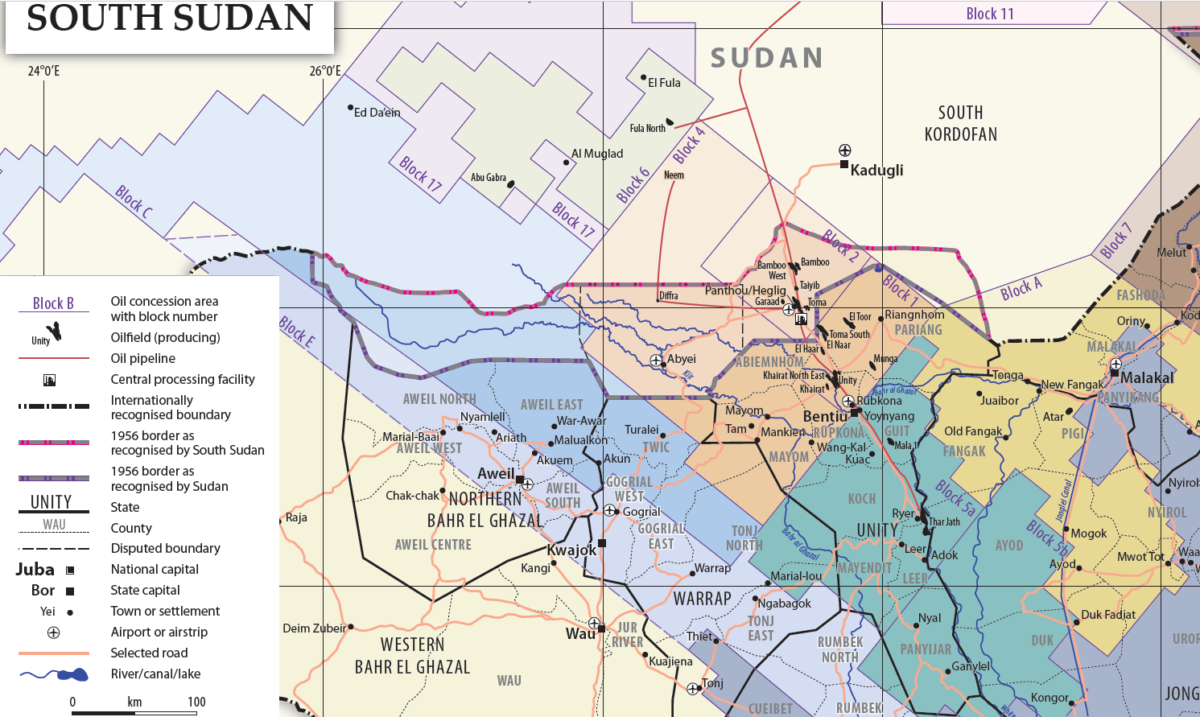

For this article, we focus mostly on the oil fields in Blocks 1, 2, 4, which are located mainly in Unity (Liech) State in the north of South Sudan, though spills and concerns over environmental pollution have also been a long-standing issue in other blocks — such as the Thar-Jath oil fields in Block 5A. Blocks 1, 2, 4 are operated by the Greater Pioneer Operating Company (GPOC) with companies from China, Malaysia, India, and South Sudan working together.

Blocks 1,2, and 4 in South Sudan (source: PAX’s Scrutiny of South Sudan’s Oil Industry)

The impact of oil exploitation with the use of satellite imagery in the Block 5A oil field and the relation with conflict was already documented back in 2009 for ECOS using NASA’s LandSat 5 and 7 to read the landscape.

Other sources we use for high resolution imagery are Google Earth Pro, with historic imagery going back to early 2000’s depending on the location, Terraserver’s high resolution imagery previewer with imagery from MAXAR, and Planet Labs.

In the medium and low optical range, we use the ESA’s Sentinel systems, in particular Sentinel 2 and 3, but also Sentinel 1 (radar imagery) and Sentinel 5p (with sensors for air quality monitoring), all using Sentinel’s Hub EO Browser.

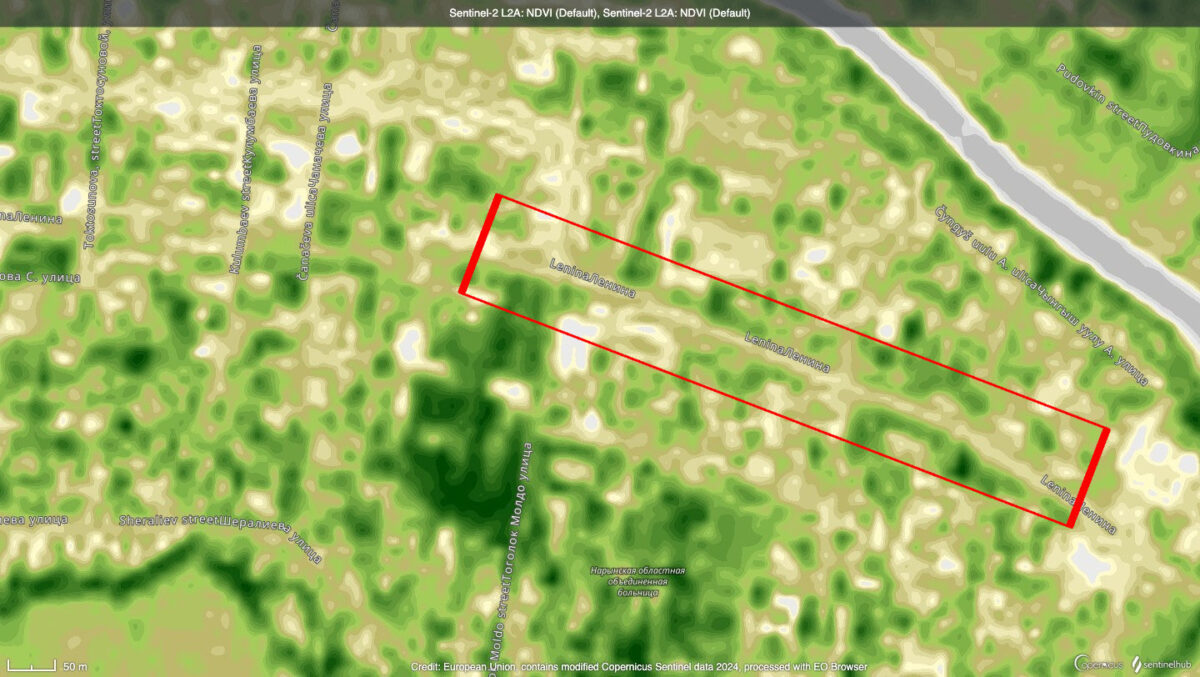

Using remote sensing to detect oil spills is largely centred on marine pollution, due to significant optical and radar differences in reflection. There is now a growing body of scientific literature looking at how to use optical imagery to detect oil spills on land, though this can prove to be more difficult considering that there are more variables in the natural environment. These spills impact vegetation and differences with healthy vegetation can help detect the spills, as demonstrated by these two research papers from Nigeria. This type of research requires a more thorough approach using normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) analysis, and a more thorough remote sensing approach for geospatial information systems (GIS) experts.

For this article, we rely mainly on direct visual clues that people with a non-GIS background can apply in detecting environmental changes using publicly accessible tools, such as those listed above.

Open Sources And Social Media

Other information on the potential location of the spills was collected through social media research, using Twitter and Facebook, where citizens familiar with the spills, either locals, journalists, or people with an interest in these specific areas were posting images, videos and comments with clues as to the location and meaning of the videos.

Public data on the oil fields was gathered from various public sources such as UN Environment reports, datasets developed with remote sensing by the World Resource Institute, reports from advocacy groups such as the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (ECOS), the South Sudan Open Oil Almanac, the Energy Information Administration website, and various news articles.

2019 September Spills At Unity Oil Field

The first potential spill which caught our attention was likely located at the El Toor and Toma South oil field, as it was reported in late May 2019 that the government was setting up an environmental assessment of all oil spills in the country. It was announced that the production at Unity was to be restarted, after the field was shut down during the 2013 civil war. The production is expected to be adding another 15000 barrels a day to the overall output.

However, reports appeared in October 2019 that a major break in a pipeline caused a large oil spill equivalent to 2000 barrels, covering an area of 400m2. This incident happened on September 25, and the location was reported to be 15 kilometers north of Lalubo. Though this name does not appear on regular Google or Openstreet maps, an open source initiative called Field Maps, developed with OCHA data and Open Street Maps, can be accessed here, and shows the names of local towns and villages. This helped locating the town Lalubo (referred to as Lalob on Field Maps) , north of Bentiu, the current capital of Northern Liech State. Various spellings of the town’s name are used on maps, explaining the initial difficulty locating it.

Lalubo is located in the Unity oil field, making this the likely candidate for a spill, though there are also the nearby Toma South and El Noor oil fields. The location, 15km north, puts the spill between Unity oil field and either the Toma South (northwest) or El Noor (northeast).

A Facebook report on the spill by Radio Miraya featured an image of clean-up, though it was not confirmed that this image was from the actual spill.

Clean-up of oil spill at Unity oil field, image via Radio Miraya

The Facebook page of the parliamentarian representing Ruwen State, Ayen Mijok Kiir, featured more images from the spill, stating that the location was in Miading area of Aliny County. Aliny is also another word for Heglig, the common name given to this area on general maps, as stated in this PAX report on South Sudan’s oil industry, and also mentioning Panakuach, also spelled Panacuac in this post a week later, which is east of Lalubo. Heglig lies in a contested border area between Sudan and South Sudan — it is officially in Sudan.

Oil spill in Unity, via Ayen Mijoik Kiir

With the use of Sentinel-2 Color Infrared filter for vegetation, we scanned the area along the main pipelines, which go down the B58 road from Heglig to Bentiu. Close to Lalubo, we found a likely spill next to the road at the coordinates of 9.615538445097194, 29.6241295337677. A short timelapse with EO Browser showed the following in the period for July-December 2019

Sentinel-2 time lapse of the oil spill at the B58 road, via Sentinel Hub EO Browser

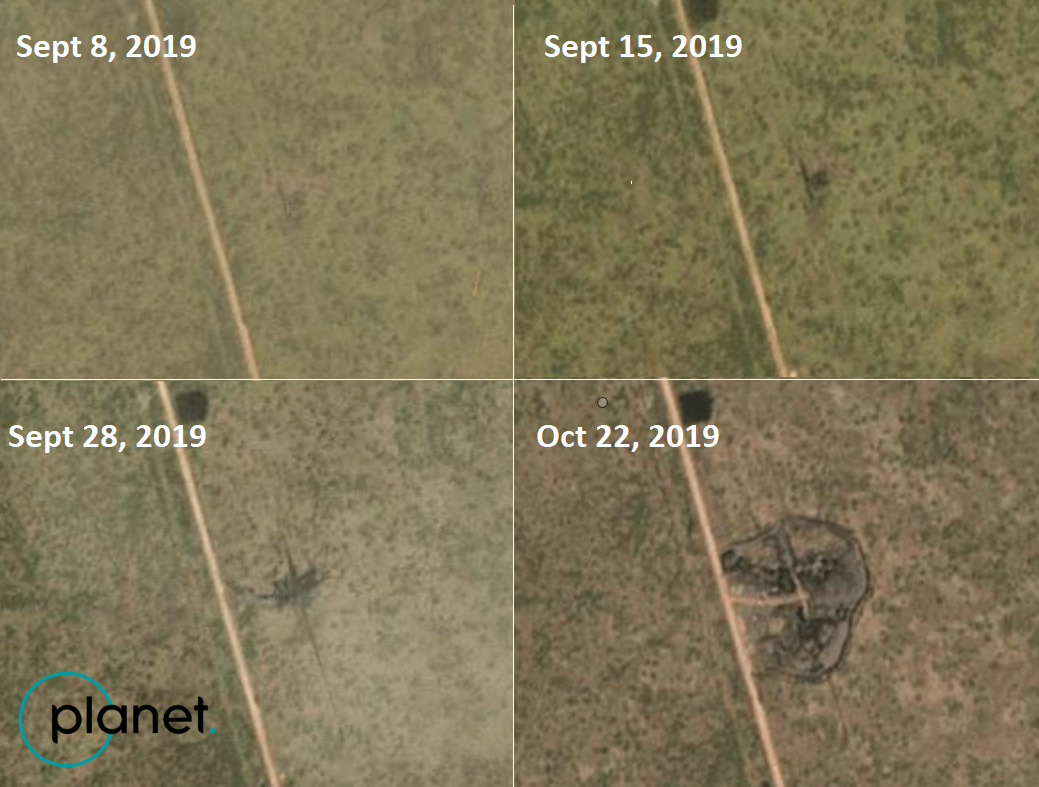

We tripled checked this with Planet Labs, as they take images more frequently, which can be helpful in identifying the time the spill started, and found that the first spill at this location must have started between September 8 and September 15, 2019. It then rapidly expanded.

Planet Labs satellite imagery of the oil spill

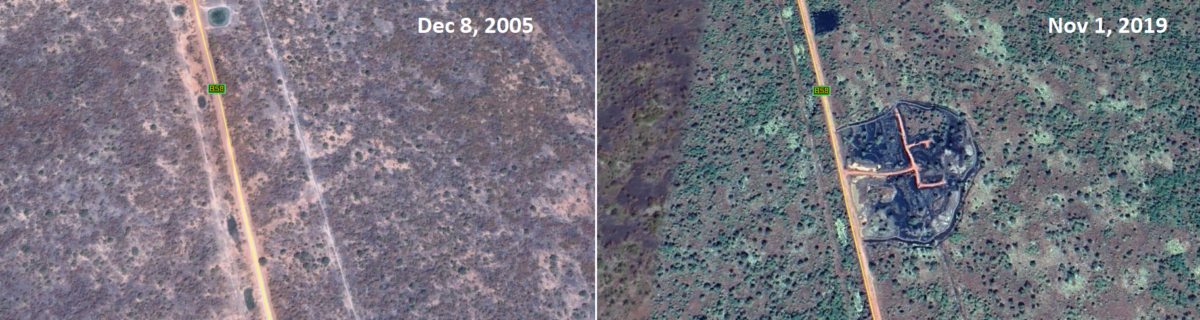

Finally, high-resolution imagery from Google Earth, dated November 1, 2019, indeed showed a large spill at this location, with imagery from 2005 showing the construction of the pipeline, which we can compare to the 2019 imagery of the spill.

Google Earth imagery comparison of the Unity/ road B58 oil spill area

When we zoom in, a truck can be seen working at the location, likely doing clean-up and remediation. A wall of soil, together with a ditch, is constructed to prevent oil from flowing over the nearby land.

Google Earth Zoom in of the reported oil spill

However, the total area polluted inside the ring is roughly 100m2, which is considerably less than the 400m2 reported earlier by the government, or the 2km2 reported by the local MP. It could very well be that we missed a larger spill, but this is the only one we could identify so far with the publicly available remote sensing tools and open source information.

A Tinderbox In The Making

In November, another spill was reported in Budang County, near the Unity oil field, which led to the evacuation of 2000 people. The search for this spill proved to be particularly difficult, as in the end of October and early November bushfires started to scorch the South Sudanese savannas, leaving large swathes of soil burned black. The use of optical satellite imagery to locate oil spills thus proved to be very difficult.

As can be seen on the Sentinel-2 imagery of the Unity and Toma South oil fields below, the fires are rapidly progressing near towns and oil facilities. This is a seasonal event, as the rainy season ends, while north eastern winds and sparks from charcoal production make the drylands vulnerable to large bushfires.

Sentinel-2 time lapse of the bushfires in South Sudan via Sentinel Hub

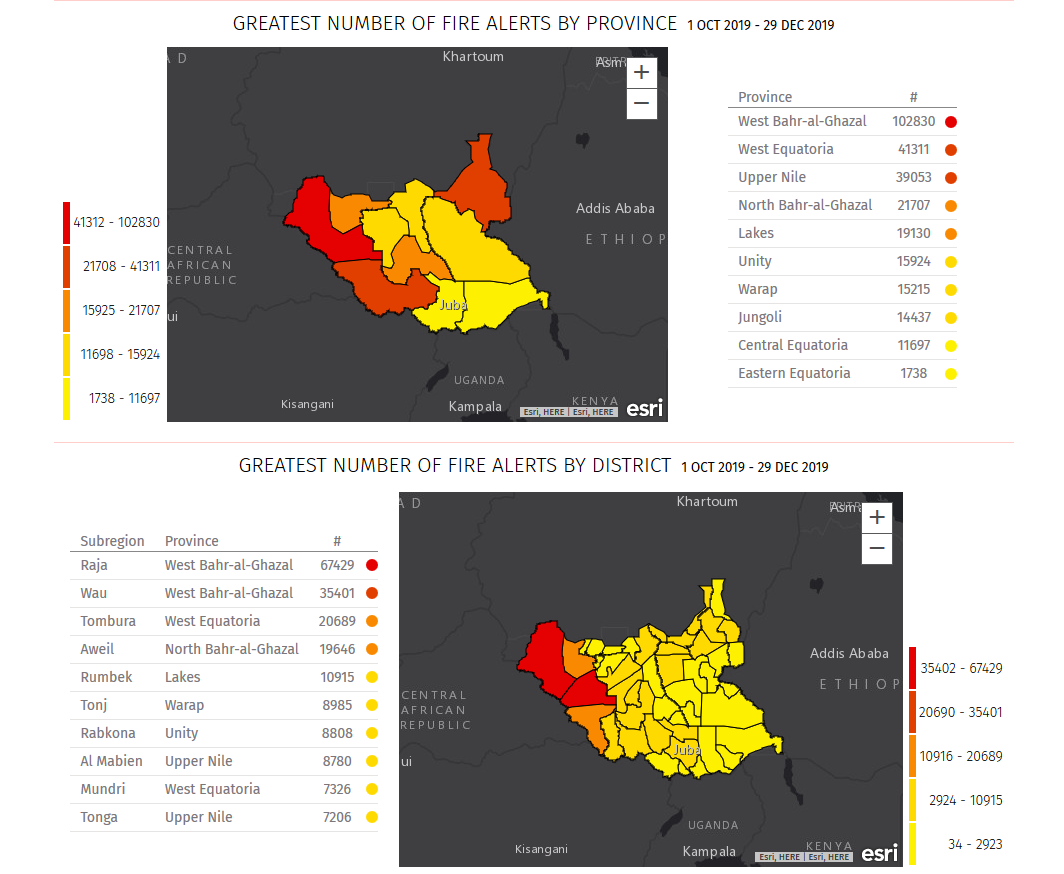

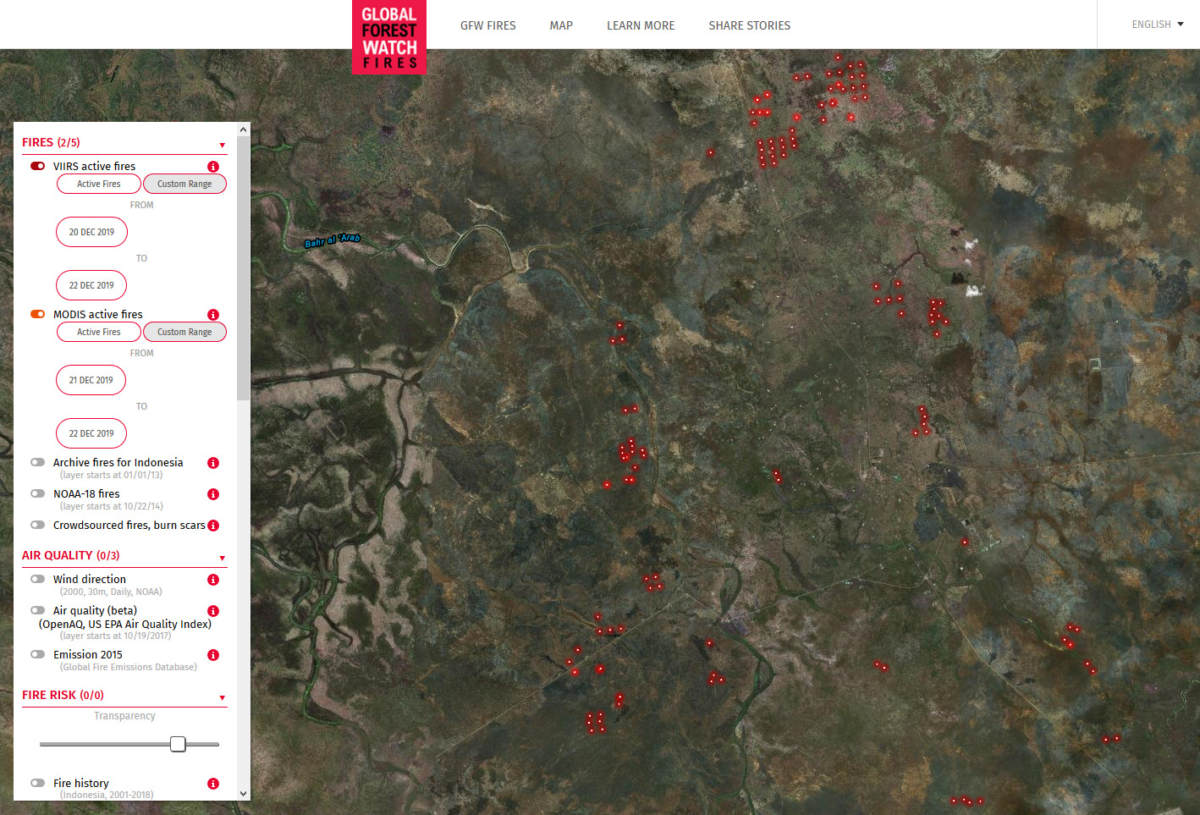

We can also use the helpful tool developed by the World Resource Institute, that made the Fire Report map for their Global Forest Watch application, utilizing remote sensing data from NASA’s MODIS and VIIRs satellites. The data for the (pre-2017 reference system) Unity district shows that 15924 fires alerts were reported, with 8808 fires in Rabkona, the northern part of Unity.

Screenshot of the Global Forest Watch Fire Report map, via World Resources Institute

On Sparks And Space

The problem with these fires became apparent on December 22, 2019, when a video was posted online showing a large fire with a black smoke cloud, claiming it was on Unity oil field in Northern Liech State. In order to geolocate the video, we used VLC Media Player and the Hugin application to stitch together screenshots and make a wide-area view of the video. A tutorial on how to do this can be found at Amnesty Citizen Evidence Lab.

Panorama shot of the oil fire, made with Hugin

Soon after, Twitter user @Maura_Ajak89 posted a translation of the conversation that can be heard in the video (archived version here).

Initial sources indicated that the spill was 30km north of Bentiu, mentioning the Unity oil field. We started off using the Global Forest Watch Fires application to see if there were specific fires in that area:

Screenshot of Global Forest Watch Fires, December 21, 2019

We then looked at Zoom Earth, which uses NASA daily satellite imagery, on December 21. We spotted some grey smoke plumes, though the grey/white colour is more associated with bushfires, not with burning crude oil or oil waste.

Screen shot of Zoom Earth, December 21, 2019

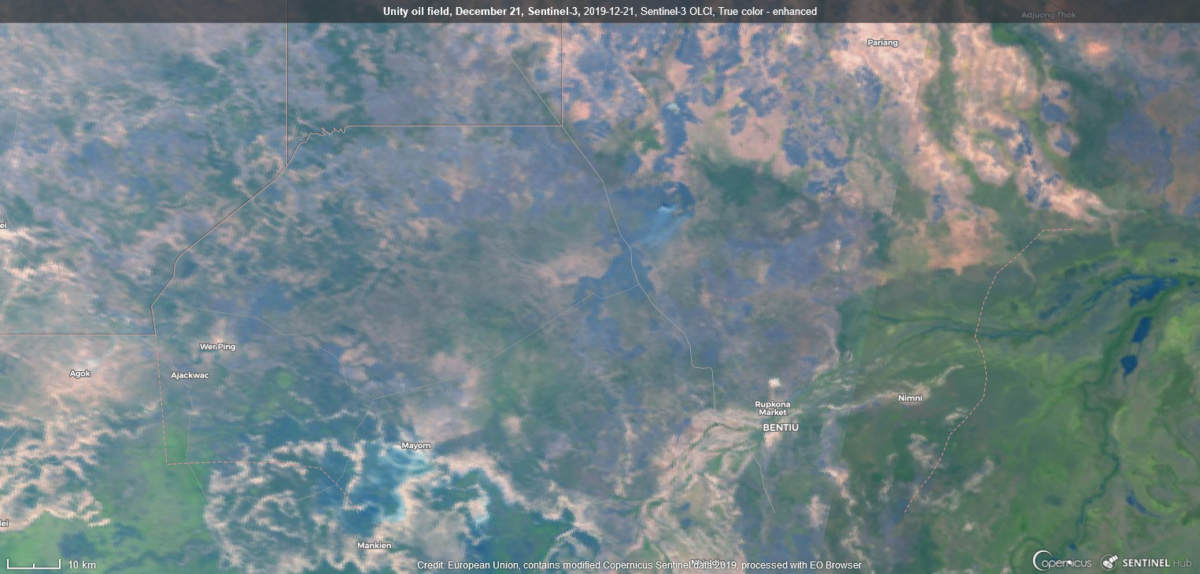

Another possible option for daily imagery is Sentinel-3 imagery, also available via Sentinel Hub’s EO Browser. The image for December 21 doesn’t show a black burn oil plume however, only white smoke from burning bushes in the centre of the image at the Unity oil facilities.

Sentinel-3 satellite imagery of Unity, December 21, 2019. Sentinel Hub/ESA

As these tools didn’t yield any helpful results, we continued our search with other means. Google Earth has updated imagery of the area from November 2019, which was helpful in searching for clues.

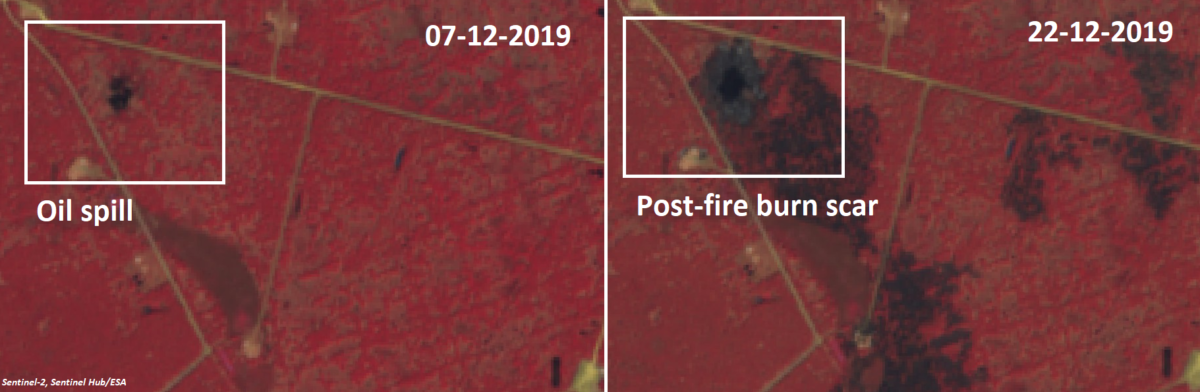

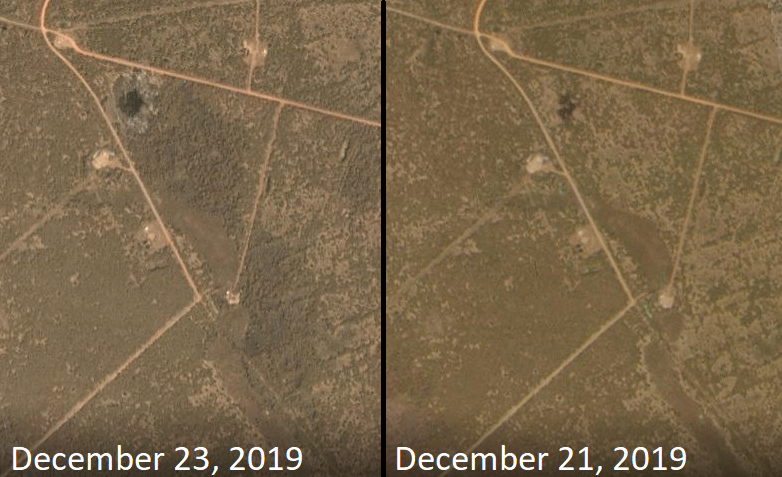

Scanning the area, various potential spills could be spotted, but often these were oil waste ponds near boreholes. We combined this imagery with Sentinel-2 images in the period August-December to see where there are any significant changes in the vegetation. We spotted one location with Sentinel-2 imagery on December 22, showing burn marks that were too small for a wildfire but significant enough to investigate.

With the Historic Images tool, we can see what is happening at the location in previous images, and what these images show is that a pipeline is running through that area in 2015, while the 2019 imagery shows us the oil spills

Oil spill at Unity field, comparison with Google Earth

A closer examination with Sentinel-2 imagery before and after the reported incident, does show that area with burn scars at the spill site with additional burn scars of the nearby bushes.

Oil spill and burn marks, Sentinel-2, Color Infrared (Vegetation) index. Via Sentinel Hub

To double check, we also used Planet Labs imagery of the same site, clearly showing the distinct burn marks for the large fire, with the additional benefit that Planet Labs had more updated imagery of before and after the incident.

Based on these images, we can confirm this is the location of the burning oil spill at Unity, that occurred in the afternoon on December 21, 2019.

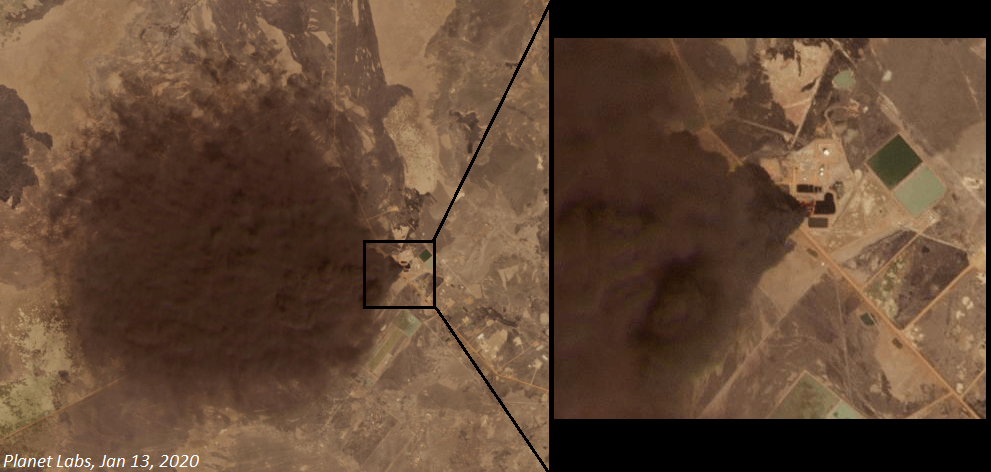

Another large burning incident took place on January 13, 2020 at the El Toor oil facility in Ruweng, where during an alleged welding incident, badly maintained oil pools caught fire, resulting in a massive oil waste or crude oil burn-off.

Burning oil pond at El Toor’s oil facility, January 13, 2020. Via Facebook

Burning oil pond at El Toor’s oil facility, January 13, 2020. Via Facebook

The large smoke plume was clearly visible with Planet Labs imagery and a video of the burning oil ponds can be found on Facebook

Burning oil pond at El Toor, January 13, 2020 via Planet Labs

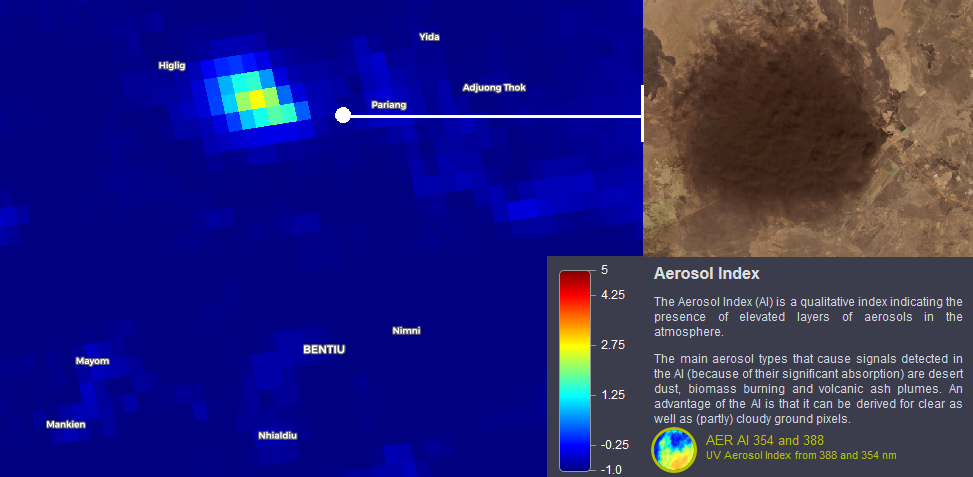

New remote sensors systems, such as the ESA’s Copernicus program Sentinel-5p satellite, can even help visualize the air pollution caused by the oil fire, as visualized here with the help of Sentinel Hub’s EO Browser using the Aerosol Index.

Air pollution from burning oil pond at El Toor seen with Sentinel-5p, via Sentinel Hub/ESA

Toma South And El Toor Facing Multiple Oil Spills In December

Apart from these burning oil spills, various oil spills were reported on social media, wherein photos were posted on Facebook, claiming an oil spill at the Toma South oil field, which is located in the northern part of Ruweng state. Toma South is an oil field that witnessed severe fighting during the civil war in 2013, and was out of operation for years before being reactivated in 2018.

The past conflict likely lead to maintenance issues and erosion of the pipeline. An AFP video from 2010 from this area already shows oil pollution, which we geo-located to the Toma South oil facility. The video covers both this oil field and the El Noor facility, while another Al Jazeera video from 2018 also features the Toma South facility in a item about health concerns

Screenshot of video at Toma South, AFP, 2010

Geolocation of 2010 AFP video at Toma South oil processing plant

North of the Toma South facility lies the El Noor oil field, which is currently operational again, but was long abandoned after fighting erupted in 2013, leading to a lack of maintenance and oil spills, as reported in this Al Jazeera video.

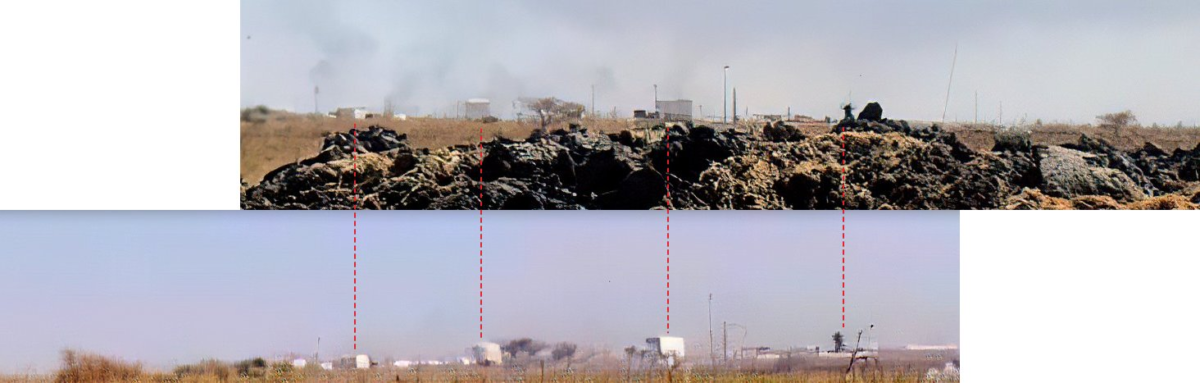

Meanwhile, though the images posted on Facebook in December show an oil spill and some oil infrastructure building in the near distance (in red) and the clear electricity lines on the right (in green), we faced difficulty in geolocating this small spill.

Colour boxed image of an oil spill at Toma South, December 2019

We searched Facebook messages reporting on the oil spills and contacted people on Facebook who wrote about this to get additional information. One of them shared images and a video of the spill at this locations, which he received from a local source. Yet these images were from a later date, as new spills were reported in the area on December 29, 2019.

Clean-up of oil spills at Toma South, December 2019. Via direct source

Clean-up of oil spills at Toma South, December 2019. Via direct source

With the help of Timmi Allen (@Timmi_allen on Twitter), the images were enhanced to get a better outline of the buildings, which helped identify the structures. As multiple sources stated that this was at the Toma South oil field, the search to match the images started here by checking the structures.

Enhanced images of the oil spills at Toma South, December 2019

We then matched them based on the structure, with thanks to Twitter user Samir @obretix

Alignment of structures, via Twitter user Samir @obretix

We then started to look for changes in the landscape during that period that could be an indication of a spill, and was different enough from bushfire burn scars.

The video we received could provide some additional clues as to the surroundings.

Again, with the help of the Hugin plug, we made a panorama shot of the video:

Panorama shot made with Hugin of the video

In order to find the location, we looked at the shadows of the individuals, using the Sun Calculator, which shows the images was taken from the north-northeast. This helped in the geolocation of the images.

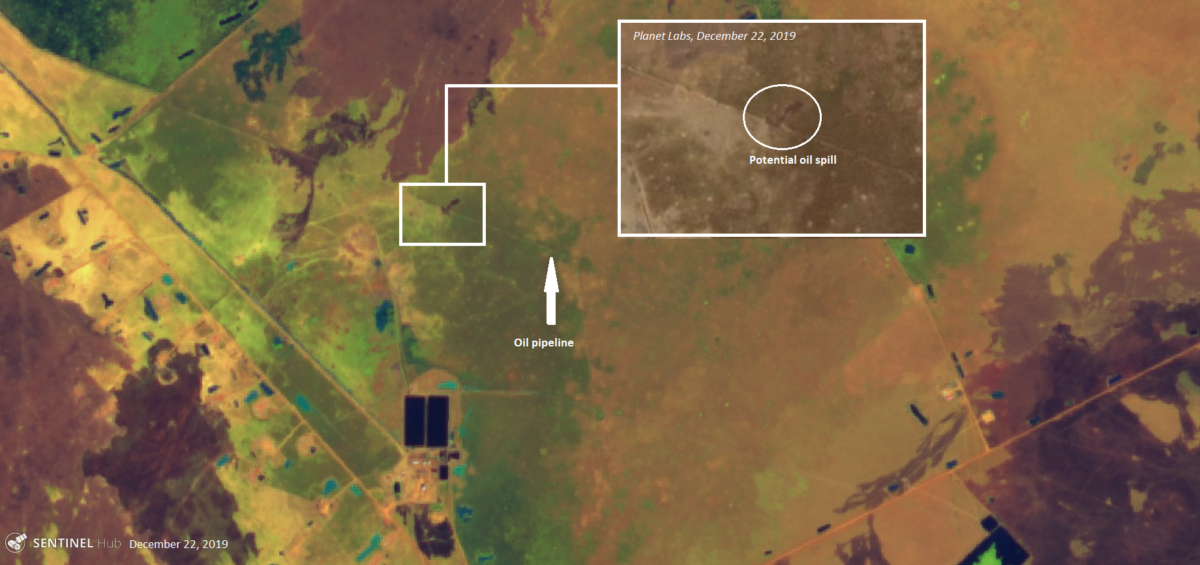

On all images, there is a power line going south, which is also visible on Google Earth imagery. We could now move on to look at changes in the landscape in the periods where the spills were reported. Sentinel-2 images without cloud cover are available for the period of December 17 and 22. There, we saw two possible locations of the spills.

Time lapse of the oil structures north west of Toma South, Sentinel Hub/ESA

Overview of potential oil spill sits at Toma South with Sentinel-2, Sentinel Hub/ESA

However, we do not have full confirmation if the images of the latest leak were at this specific sites, and high-resolution imagery would be needed to confirm this.

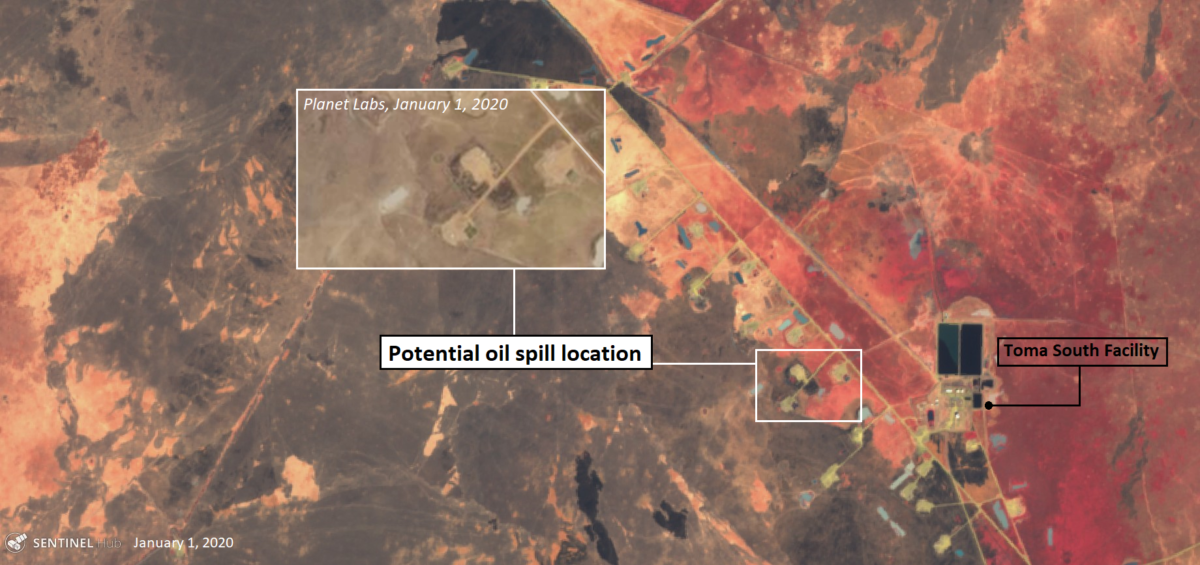

Both these locations could be the source of first reported images, it fits in the view line from the photos. Though the second image shared seems to be taken at a more southward location. This could be the source of the image related to spill reported to have occurred on December 29, 2019. The location of this spill is likely the be at the pump sites, a bit further south, near the Toma South FCP, as a colour change can be seen on Sentinel-2 and Planet Labs satellite imagery at this location on January 1, and it is less likely to be caused by a bush fire considering the fact that it’s brown soil without vegetation that turned black.

Oil Spills That Were Not Reported

While exploring satellite imagery of this area, another potential oil spot was seen at this location, a few hundred meters northeast of Toma South FPF along a pipeline. Surrounded by burn scars from bushfires, this location stood out, as the imagery indicated that some kind of clean-up operation could have taken place here.

Potential oil spill, north-east of Toma South oil facility. Imagery via Planet Labs/Sentinel Hub/ESA

In the following days, it seems some operation took place at this location, as there are visible changes in the structure and colour of the soil with Sentinel 2, and on Planet Labs imagery between December 22 and January 6, where on December 30 and December 31 the changing black spots could indicate some soil removal, though high-resolution imagery would be needed to get a clear view on this location and confirm the oil spill.

Zoom-on on potential oil spill at Toma South, imagery via Planet Labs

Conclusion

The development of South Sudan’s oil industry has come with high social and environmental costs. Tens of thousands of people were killed during the 1997-2003 oil war, and sub-standard environmental practices have been reported since production first started.

In 2019, foreign oil companies started to bring fields on stream again that had shut down during the early days of the 2013-2018 civil war. They also invested substantially in enhanced recovery techniques. Apparently, no similar efforts have been made to clean up the industry’s legacy, despite legal requirements to do so. Multiple recent spills and fires suggest that the industry does not uphold acceptable health, safety, and environmental standards. Meanwhile, the government of South Sudan does not adequately monitor and enforce compliance with laws that regulate the industry’s social and environmental impact.

It is too early to tell whether the recent announcement by the government of South Sudan of a tender for an environmental audit of the oil industry indicates an end to 24 years of neglect. The Petroleum Act of 2012, section 100(8), obliges companies to “carry out and pay for an independent social and environmental audit, in compliance with international standards to determine any present environmental and social damage, establish the costs of repair and compensation and determine any other areas of concern.” The Transition Agreement, article 7.2, on the Government Right to Carry out HSE Audit, determines that the Government shall select a consultant to carry out “one audit of health, safety, environmental and social conditions, practices and other matters relating to the health, safety, environment and social impacts (…).whether before or after Secession (..).”

It seems that the current tender is meant to fulfill the requirements of the Petroleum Act, even though the government’s website suggests that the audit will be environmental only and not cover the industry’s social impacts.

It is urgent to tackle the full legacy of South Sudan’s oil industry. In Sweden, two managers of Lundin Petroleum will soon be indicted for alleged complicity in war crimes during the early days of the industry. If South Sudan’s politics stabilizes in the course of this year, widespread popular anger about the industry’s persistent misconduct will become impossible to neglect. China’s CNPC and Malaysia’s Petronas will have to radically change their approach, account for their actions, and address their impact.

Based on different media reports, we have identified various locations where oil spills contaminated land, resulted in large oil fires, and sparked social unrest in nearby villages. We found the location of various large oil spills and subsequent oil fires in Unity oil field, oil spills at the Toma South oil facilities, and documented the various media postings related to oil fires at the El Noor oil facility. Their full impact on lives and livelihoods needs urgent on-the-ground investigation.

Open source investigation combined with freely available earth observation and remote sensing tools can be a powerful instrument to document and visualize incidents like those described above and can be a helpful tool to hold both oil companies and governments accountable.

Clearly, a more sustained and mainstreamed effort is needed to address the direct and long-term impacts of armed conflicts on the environment, the responsibility of governments and (international) corporations in relation to dealing with natural resource management and dealing with toxic substances in conflict-affected industries. Community concerns over the environmental impacts needs to be addressed through implementing local legislation, and properly monitored. We hope this open source resource endeavour has been a small contribution to that process.

I would like to thank the following people for their outstanding help and expertise: Azona Mabil and Rapper Hot Dogg from South Sudan for additional images and videos, Noor Nahas @noornahas1 and Samir @obretix for help with geo-location, Timmi Allen @Timmi_Allen for enhancing the imagery, Egbert Wesselink and Kathelijne Schenkel for their review on South Sudan’s oil industry.