Ghana's Atewa Forest: Monitoring Mining Which May Threaten Water Sources

Executive Summary

Ghana has agreed with China to develop its bauxite industry, but concerns have been raised that mining activities in the Atewa Forest Reserve may threaten the country’s water supply. What can open source information tell us about the forest and the mining activities? While no bauxite mining is taking place to date, satellite imagery does show the large scale of illegal gold mining happening at the reserve’s frontiers. Small scale mining within the forest cannot be detected, though that does not mean it is not taking place as it is usually conducted from canopies and thus covered by trees. If bauxite mining will indeed start to take place, large facilities will be needed which can be easily observed from space.

The Bauxite Deal with China

At the end of June 2017, the Republic of Ghana signed a $10 bn Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the People’s Republic of China to develop its bauxite industry. This was announced by Ghana’s Senior Minister Yaw Osafo-Maafo at the sidelines of an investor conference in London, according to Reuters.

Ghana’s economy had a tough time in 2014 as it suffered from a fiscal crisis and accompanying “tumbling commodity prices following years of economic expansion at around 8 percent on the back of gold, cocoa and oil exports”, Reuters writes. To boost the economy, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo, who took office this January, has outlined a programme to create jobs in the private sector and through rural development.

The deal with China appears to support President Akufo-Addo’s plan, as it includes the construction of 1,400 km of a planned 4,000 km railway network that would link bauxite mines and production sites. Details including interest rates and terms have yet to be decided. The China Railway International Group Limited is the actor providing $10 bn, Star FM Online reported, while earlier reports also mentioned the Chinese Development Bank.

Another number of MoUs totalling $5 bn were signed by Ghana with other Chinese companies, including the China National Building Materials and Equipment Import and Export Corporation (agreed to build a $2 bn facility with the private sector led by the Association of Ghana Industries), the China Development Bank (agreed to unfreeze a $2 bn loan), and the China Exim Bank (committed to dispense about $1 bn to Exim Bank Ghana to support infrastructure and business development).

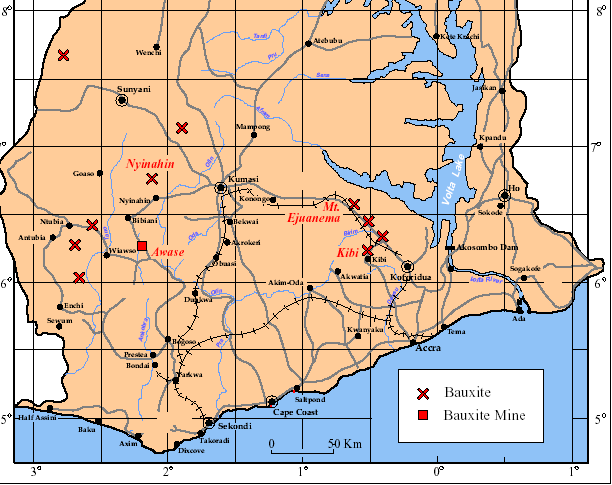

The Ghanaian government has rejected claims it is borrowing this money. Instead, Vice President Mahamudu Bawumia told reporters that it will give “less than 5% of its bauxite reserves in exchange for the money.” Bauxite is the main raw material in the production of aluminium, and Ghana has large reserves based in the Atewa Mountain Range (around 150-180 million metric tonnes), at Nyinahin (around 350 million) and at Awaso (around 1 bn).

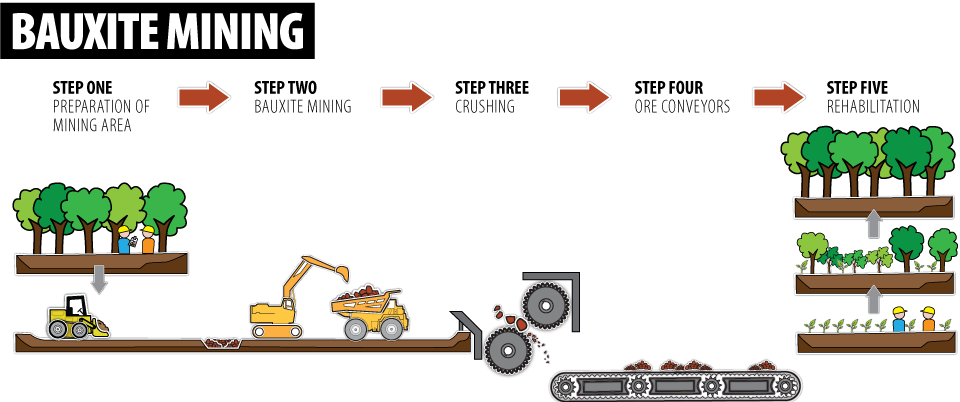

Bauxite mining. Source: Australian Aluminium Council Ltd.

Under the deal with China, Ghana’s integrated aluminium industry will be developed, including the Nyinahin and Kyebi bauxite mines and an aluminium refinery, Vice President Bawumia said. Around $460 bn can be made of about 960 million metric tonnes of bauxite reserves in the coming years, he said, asserting that the deal will benefit the ordinary Ghanaian.

Map of bauxite deposits in Ghana. Source: G.O. Kesse, The Mineral and Rock Resources of Ghana (Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema, 1985), via A Rocha Ghana.

However, both locals and government officials have raised concerns that the bauxite mining near Kyebi in the Atewa Forest Reserve could have far reaching implications on the environment, most significantly compromising the water supply for up to five million Ghanaians.

The Atewa Forest Reserve and the Mining Activities

Ghana’s Evergreen Forest

Around 70 km north of Ghana’s capital Accra lies the Atewa Forest, recognised as a globally significant biodiversity area, as it houses a great variety of plants and animals including many rare and endangered trees, primates, and amphibians. Being one of Ghana’s two remaining upland evergreen forests, it was declared a Forest Reserve in 1925.

The forest is the source of three major rivers: the Densu River, the Ayensu and the Birim (an important but declining source of diamonds). Many agricultural communities along the banks of these rivers depend on them as the only water source, as well as inhabitants of the Ghanaian capital. The total beneficiaries of the drinking water are estimated to be around 5 million people.

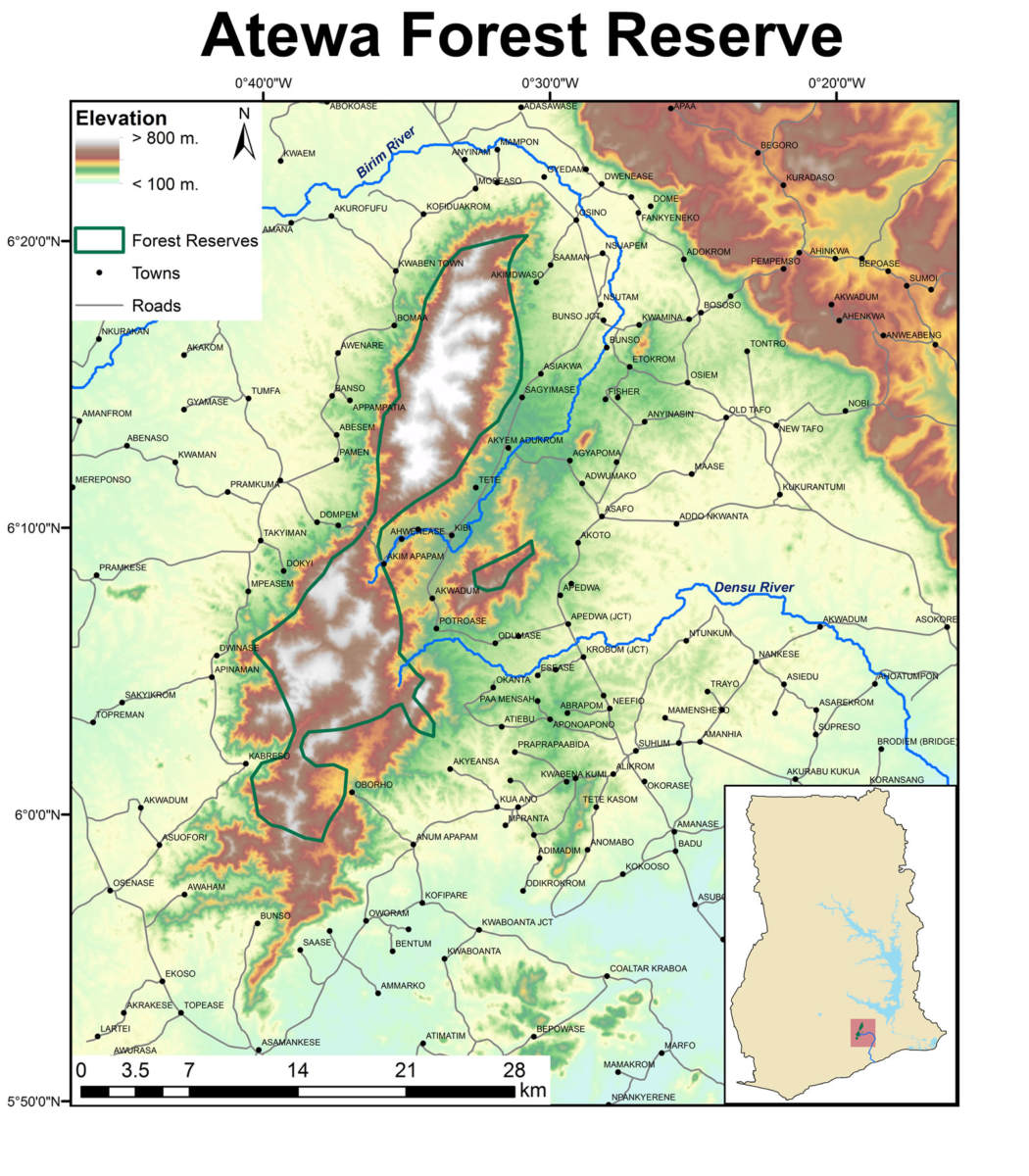

A map of the Atewa Range in Eastern Ghana, showing the Forest Reserve’s boundaries in green, and the rivers highlighted in blue. Source: Save Atewa.

Threats to the Atewa Forest

In recent decades, the Atewa Forest Reserve has been under pressure by a number of threats, such as farm encroachment (which is restricted since a few years now), bushmeat hunting, illegal and unsustainable logging, artisanal gold mining (referred to as ‘galamsey’ in local language), and lastly, bauxite mining and exploration. All of these factors undermine the river’s capacity to absorb and filter rainwater. The last listed factor is increasingly becoming a concern for officials and locals alike, especially given the new MoU with China.

A ‘galamsey’, an illegal gold mining site, on the edges of the Atewa Forest Reserve. Source: Dutch Embassy in Ghana.

Two killed primates, reportedly killed for bushmeat in the Atewa Forest Reserve, were posted on Facebook. Source: Dawuni K. Richard.

Given the new MoU with China, several civil society organisations have asked their government to reconsider the terms of the MoU. Gold mining has already had severe consequences, including turning the rivers from clear water into muddy streams, and toxic metals such as mercury entering the water supply, making it unsafe for consumption.

While explicitly stating that they are not against bauxite mining in general, they request their government to take the Atewa Forest Reserve into protection for several reasons.

Firstly, the Atewa Forest Reserve is home to the sources of three rivers which makes it the most important water tower in Ghana, providing water for over 5 million Ghanaians on a daily basis. Illegal gold mining activities are already threatening the water supply, as quality monitoring and assessment of major rivers by Ghana’s Water Research Institute confirmed in May 2017. This is highly likely to get worse when bauxite mining starts in the area.

From 2008 to 2016, most of the illegal gold mining took place around the edges of the Atewa Forest Reserve. Many locals upstream did not have much choice other than illegally digging for gold, as claimed by Ntiamoa Eric, an artisanal gold miner speaking to A Rocha Ghana (one of the organizations that published the joint call to their government):

“In reality, there are no jobs in this village. Growing cocoa is the only other job we have here. We might look young but we all have but we all have small cocoa farms. But cocoa farming is such you need other source of income to support it.”

Local communities near the Atewa Forest are said to have little choice than to mine, as there are little other job opportunities, Ntiamoa Eric claims while speaking to A Rocha Ghana. Source: A Rocha Ghana.

Anti-Galamsey Campaign

It was only during the new government’s term, which started in 2017, that there was a commitment to drive the artisanal miners out, Daryl Bosu claims while speaking to Bellingcat via Skype. Mr. Bosu is an activist with A Rocha Ghana. A video promoting the anti-galamsey hotline can be watched below.

“At the time there was this massive scale of gold mining, the state was sleeping, so people were just out and digging their way trying to see what they could find. All has come to an hold since last year, and so far it has been successful to drive out these illegal galamsey activities. If you do mining, do it sustainable, the government basically says.”

An anti-galamsey task force deployed by the government under the name “Operation Vanguard” enforces the country’s laws against illegal practice of gold mining. While around 100 illegal miners have been arrested as of August 10, 2017, the anti-illegal mining task force is “facing stiff opposition from illegal miners“. The Ghanaian government is said to spend around fifty million Ghana cedis (around 11 million USD) on the anti-galamsey campaign, Ghana Web reported.

However, Operation Vanguard has come under backlash in August 2017 for reportedly burning the equipment and property of illegal gold miners’ property would be burned. A video published on YouTube on August 10, 2017, appears to show such a burning of an excavator.

Leaving gold mining aside, the renewed interest in bauxite mining in protected forest reserves is problematic, Mr. Bosu believes. Many of the illegal small-scale mining was largely driven by Chinese immigrants in Ghana, Joshua Amponsem, another Ghanaian environmental advocate, claims in a guest post on Deutsche Welle. Therefore, the “weariness of the citizens is very strong”.

The main issue at stake is thus the provision of water. But besides, the Atewa Forest Range contains unique and rich biodiversity and is recognised as such. No fewer than 228 bird species, 52 mammal species, and 32 amphibians are home to the forest. Some of these flora and fauna have not been found elsewhere in the world.

Furthermore, the forest holds longstanding cultural importance for the Akyem Abuakwa people and has a rich cultural heritage, and the provisioning services (water, non-timber, climate amelioration services, tourism, cocoa farming) of the Atewa Forest are said to be worth millions financially to local communities, downstream residents, and the national treasury, according ‘The Economics of Atewa Range Forest’.

In a bid to protect the Atewa Forest, the organisations are calling upon their government to upgrade the area to a National Park.

Miners working near the Birim River, which has already been heavily polluted by illegal mining activity. Concerns have been raised the river may be polluted even more now that a deal with China would increase bauxite mining near the source of the river. Source: City 97.3 FM.

The River Birim its source is situated in the Atewa Forest Reserve. The river feeds the Kyebi water treatment plant. Reportedly more than 5 million Ghanaians are dependent on the water of the three rivers which originate in the forest. Source: City 97.3 FM.

Potential Bauxite Mining

Inusah Fuseini, Ghana’s former Minister of Land and Natural Resources and current opposition Member of Parliament (MP), suggested that bauxite can be exploited in Atiwa from the northeastern side, as he claims this would not affect the source of the Birim River.

“There are two major deposits of bauxite in Ghana,” he said while speaking to BBC’s ‘Focus on Africa’, “the bigger one is the Nyinahin deposit, and not the Atiwa one … Therefore, what we are talking about can be done without touching the Atiwa [Forest].”

Senior Minister Osafo-Maafo responded to MP Fuseini’s comments that bauxite development in Ghana can be done without compromising the country’s forest reserves and rivers, Pulse reported. The mining is also opposed by Ghana’s National Democratic Congress, though the opposition’s party stance has also been criticised for playing “Jeremiah” (worth noting that a reverse image search shows that the picture used with the article is actually a bauxite mine in Malaysia).

Between the mid-2000s and 2014, a number of organisations have already conducted prospecting and exploration missions in search of bauxite, including ALCOA (Aluminium Corporation of America), RUSAL (Russian Aluminium, a major Russian aluminium company applied for permission to explore the bauxite deposits near Keybi in 2011), Vimetco Ghana Ltd. (a 100% owned subsidiary of Vimetco N.V. (an international industrial group) was granted several exploration licences in 2011), and Exton Cubic Group Ltd.

All these companies withdrew the exploration missions by 2014. ALCOA, which financially supported scientific research for a rapid biological assessment of the Atewa Forest Reserve, stopped because it would hurt its international reputation, Mr. Bosu told Bellingcat. None of these companies have actually mined for bauxite.

So, will a Chinese company be the first? “I hope not,” Mr. Bosu says. “But so far, we don’t know. First, the memorandum of understanding has be defined, the details need to be discussed. When that’s done, it needs to go to Parliament. We are trying to get transparency about the process.”

In what way, if any, can satellite images help this process to increase transparency?

The Satellite Images

Satellite imagery can serve well for remote sensing of larger deforestation and mining activity, as a recent Bellingcat publication on a gold mine project in Armenia also showed.

As no bauxite mining has taken place (only exploration missions), satellite imagery can not (yet) support the monitoring of the potential bauxite mining. This may be possible in the future, as bauxite mining would require large facilities and the removal of substantial areas of forest.

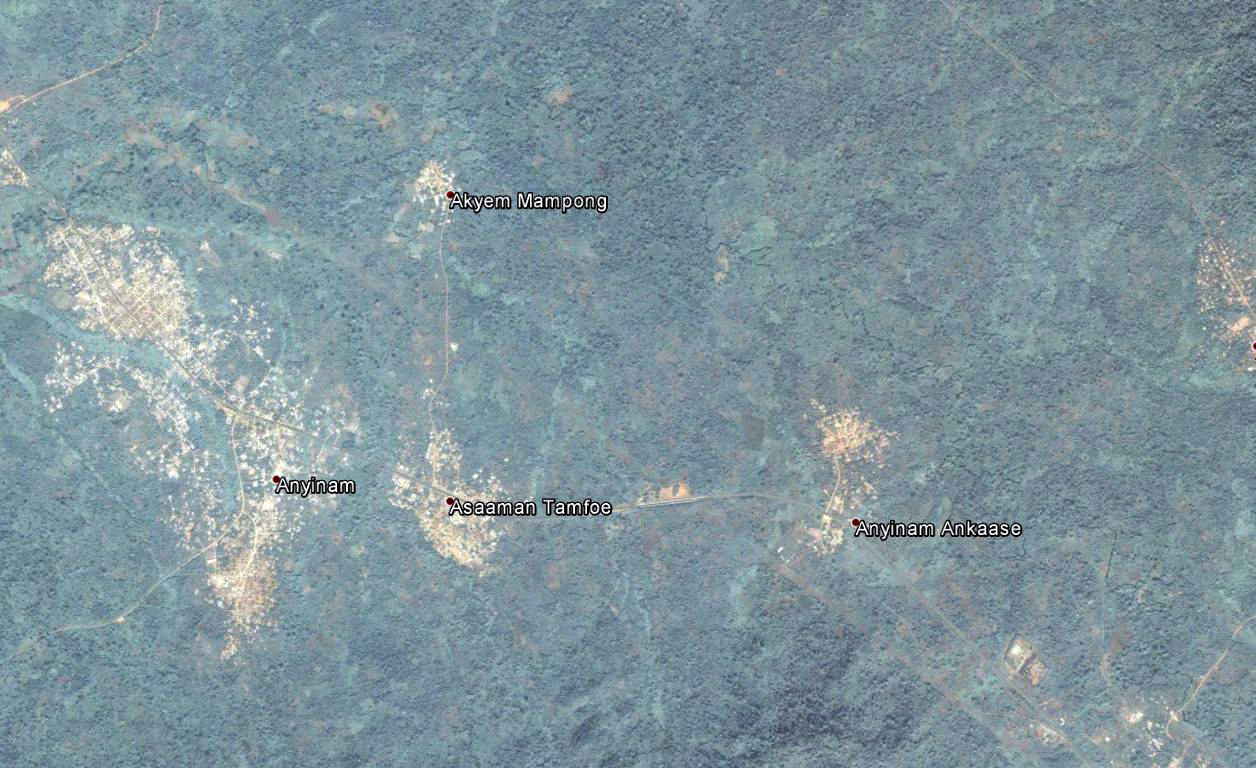

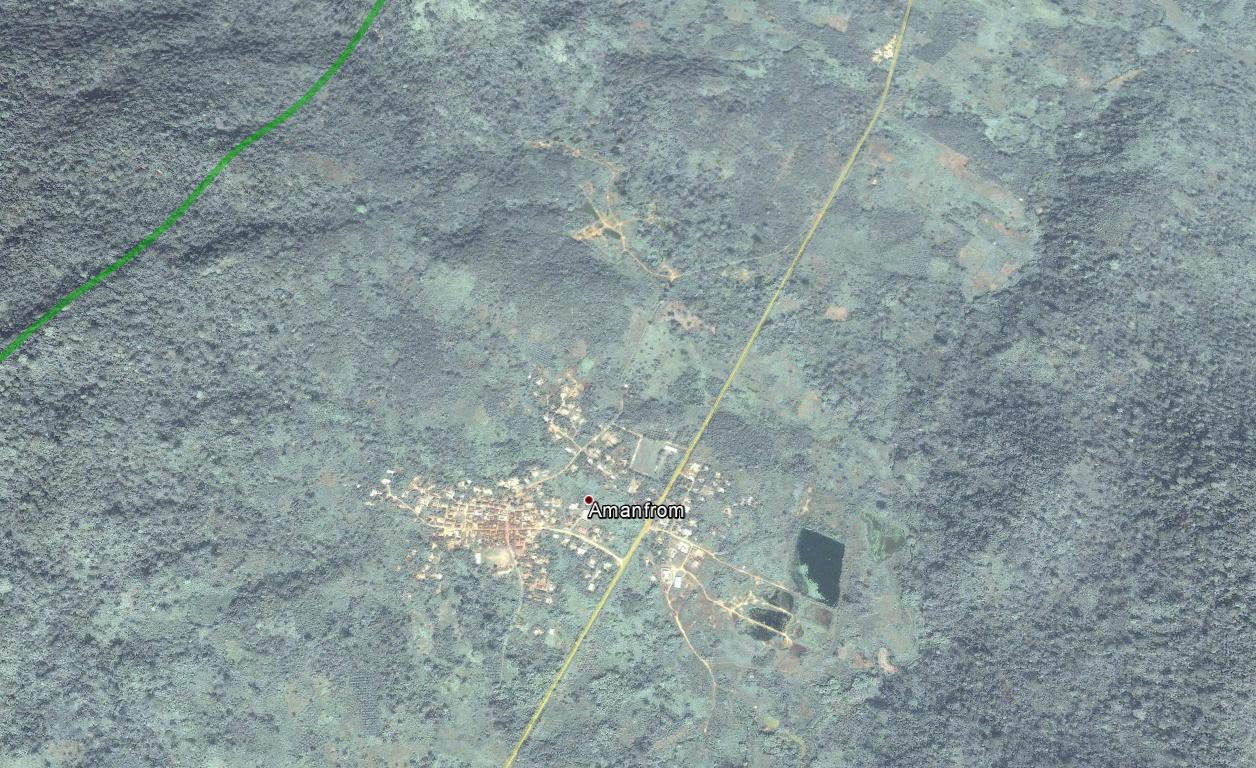

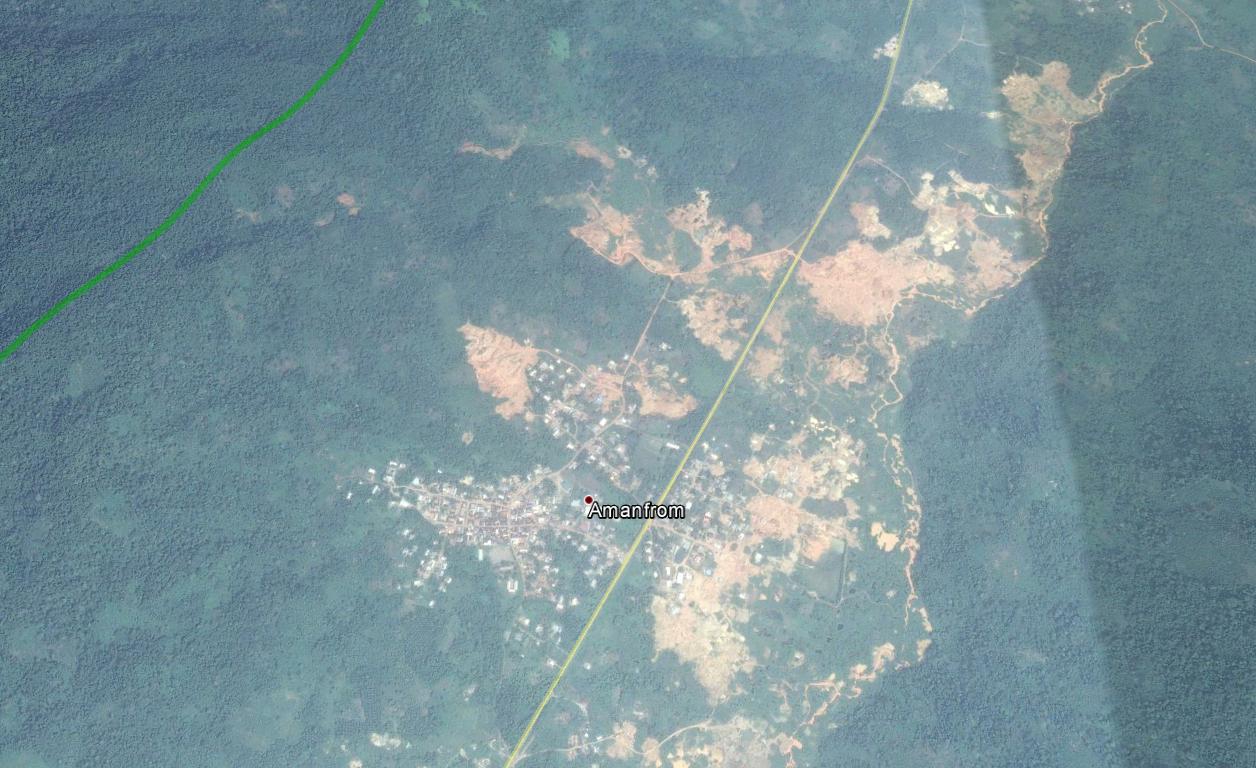

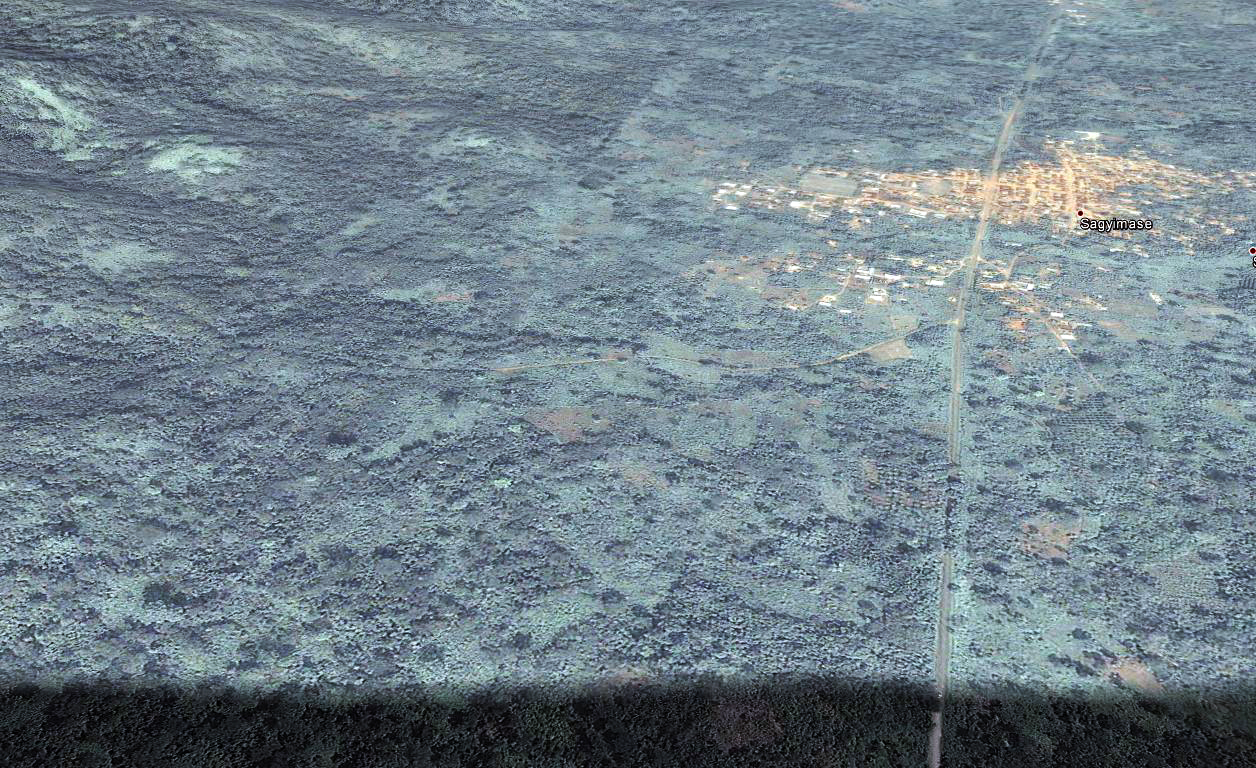

However, the increase in illegal gold mining activity in recent years, which allegedly stopped since last year, is easily discoverable on satellite imagery. As the most recent imagery is from 2014, the decrease in artisanal gold mining due to the government’s anti-galamsey campaign cannot yet be observed. Basically all of these mining activities take place at the edges of the Forest Reserve’s borders, and are so-called galamseys or artisanal gold mines.

That does not mean that there is no mining at all taking place in the Forest Reserve. This is evident in a news report that claimed illegal miners were arrested in the Atewa Forest in 2017. Satellite imagery can only show so much. Small artisanal miners are not permanently present in the forest, as it is highly protected. Instead, they sneak in and use canopies to do the meaning, making their efforts invisible on satellite imagery.

All images below were published by Google Earth.

Only one significant change could be detected within the Atewa Forest Reserve, but bear in mind that the most recent imagery on Google Earth is from December 2014.

Two make-shift gold mining spots within the Forest Reserve appear to have been abandoned between January 2013 and December 2014.

Concluding Remarks

Bellingcat will continue to monitor the possible development of bauxite mining in or near the Atewa Forest Reserve, hoping to supplement the work of local journalists and civil society actors with the expertise we can provide in open source research. So far, researchers and activists on the ground can contribute far more to the monitoring efforts of the Atewa Forest Reserve, making it important that our digital research efforts are able to potentially complement their investigative work.

We also hope to continue investigative work into the project, blending digital monitoring efforts and traditional investigative journalism. Going forward, we also hope that our monitoring efforts will raise awareness of this potential mining project, which may be of tremendous significance in Ghana, and bring about greater accountability and transparency to the project.