The Strange Tale of the Georgians in Congo

Glossary

- DRC — Democratic Republic of Congo (capital: Kinshasa)

- FARDC — DRC Armed Forces (Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo)

- FAC — DRC Air Force (Force Aérienne Congolaise)

- PMCs — Private Military Contractors, or Private Military Companies

- M23 — March 23 Movement, a Tutsi rebellion movement in Eastern DRC

- FDLR — Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, a Hutu militia in Eastern DRC

- Mai-Mai — Community militias created to defend Hutus’ interests and territories in DRC

Scope of the Research

This research aims at investigating an incident in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which reportedly involved two combat helicopters piloted by foreign staff.

The main objective is to obtain more clarity on the presence of private military companies (or contractors), also known as PMCs, in DRC in particular. The nature of their relationship with the nation-state actors active on the territory – namely, the FARDC (DRC Army) as well as the FAC (DRC Air Force) – will also be examined.

Key Findings

- The research points to the possibility that foreign military pilots active in DRC act as trainers and mentors for the local troops.

- The gathered information leads to the possibility that such pilots also take active part in FARDC military operations in North Kivu.

- It appears likely that, while the presence of PMCs in DRC has a long history, the examined presence of private military staff in Goma and North Kivu in support of the FAC was initiated, or escalated, in early 2014, in correspondence of a resurgence of conflict with one of the militias active in the province.

- Mining interests in North Kivu, in conjunction with the ineffectiveness of the FARDC, could represent a lead motive for the involvement of PMCs in the area.

Context

Map of the Democratic Republic of Congo. North Kivu (in its French denomination) is highlighted.

[Source]

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is in a state of permanent political instability since at least 1996, the year when the First Congo War started (1996–1997) as Congo was invaded by neighbouring countries led by Rwanda. The mineral-rich eastern region of North Kivu was particularly affected by that and the following civil wars, with recurrent spillovers of political and military influence from neighboring countries Rwanda and Uganda. The ongoing ethnic tensions between Tutsis and Hutus frequently escalated to armed conflict over the past two decades, with the most recent phenomenon being the March 23 Movement (M23), an armed group of Tutsi of the DRC Armed Forces (FARDC) that rebelled, and took the provincial capital of Goma in 2012. While the rebellion officially ended in December 2013, it is reported that M23 fighters remain active in the several forested and remote parts of North Kivu.

At the national level, president Joseph Kabila maintains his grip on power beyond the maximum limits of his constitutional terms, which expired in 2016. His decision to delay elections until 2018 with a pretext is contributing to further instability across the country.

Around January 30, 2017, news started circulating on both African and Eastern European media that a Mi-24 combat helicopter belonging to the FAC, the military aviation of the DRC, had crashed on January 27 in Rutshuru, North Kivu, near the borders with Rwanda and Uganda. It was said that the Mi-24 was hit by M23 fighters, which is known as being active in the area. Shortly after, press started reporting that a second helicopter was also downed by gunfire.

The first report on the Mi-24 crash in Rutshuru, published on Facebook by the Georgian military magazine “Arsenal”.

The peculiarity of the incident is in the helicopter crews of both Mi-24s. One crew, reportedly, consisted of two Georgian pilots, one of which turned out to have been taken prisoner by the M23 attackers, or transferred to a linked group; while the other crew consisted of two Belarusian men. Both crews were reportedly in DRC on “private contracts”, but it remained unclear why they were piloting — or at least on board of — FAC combat helicopters in an active conflict area.

The Helicopter

Photos of one of the two crashed helicopters started circulating on the web already on January 30. They show the remnants of what appears to be a Mi-24 combat helicopter displaying part of its registration number:

One of the first photos released of the crashed helicopter, surrounded by unidentified fighters (source).

The Congolese newspaper Politico.cd published a few photos a day later on January 31. Interestingly, the date impressed by the device — likely to be a compact digital camera — on two of the pictures is in Cyrillic script, and reads “27 Jan 2017”. Additionally, we find that the complete registration number for the helicopter is: 9T-HM 12.

Images published on Politico.cd showing a date stamp in cyrillic characters, plus the full registration number (9T-HM 12) and the tail section of one helicopter with the FAC roundel visible.

While it’s difficult to obtain absolute certainty that the helicopter in all pictures is the same one, because of the lack of points of reference in the forested area, several details seem to confirm it:

- A severed log is visible in two pictures right behind the helicopter’s cabin in three different shots, two of which from different angles;

- The damage inflicted to the vehicle’s tail appears to match in all photos where it’s visible;

- A second severed log is visible in at least two pictures while resting over the right wing of the helicopter;

- The cabin door to the rear troop-utility compartment is visible in at least two pictures as open;

- The pattern of damage to the helicopter’s blade also seems to match in all photos, with a short blade’s stump pointing loosely towards the back of the aircraft, and longer ones towards the other sides.

Composite of 3 photos of the crash scene from different angles. Contrast and brightness were adjusted for better clarity.

Composite of two images of the crashed helicopter. The log over the right wing, the broken blade pattern, and the open cabin door are visible.

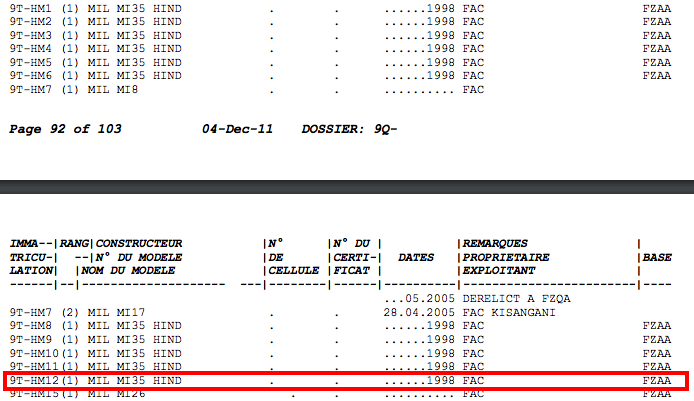

The registration number of the helicopter is, naturally, a crucial piece of information. A 2011 document purporting to reproduce a list of all aircrafts registered in the DRC explains that, for immatriculation, the DRC military aircrafts use the formula 9T-xxx, “in arbitrary manner”.

Within the same document, we find a list of helicopters registered with those parameters, including an HM12:

According to the document, registration number HM12 of the downed aircraft, as well as all other helicopters registered sequentially from HM1 to HM15 (with the exception of 13 and 14), had originally been registered in 1998 by the FAC at a base marked with the ICAO code “FZAA” — which corresponds to the N’Djili International Airport in Kinshasa, the capital of DRC.

It is important to note that the list specifies the model of the helicopters to be Mi-35 — a noticeably different aircraft from the one(s) involved in the incident.

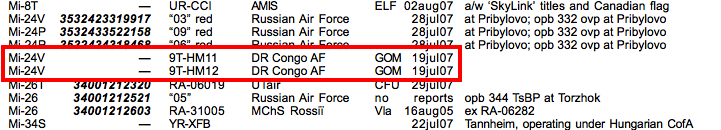

However, a list published in October 2007 by the Dutch aviation magazine Scramble appears to show that on July 19, 2007, two Mi-24V helicopters with registration number 9T-HM11 and, more importantly, 9T-HM12 were registered, again by the FAC (here named “DR Congo Air Force”), as based at an airport with IATA code GOM — a.k.a. Goma International Airport:

Goma is the capital of the North Kivu province, located approximately 75 kilometers south of Rutshuru, where the crash reportedly happened. It hosts an international airport that, despite having been substantially damaged by a volcano eruption in 2002, is still operative to this day. It is important that we are able to track the helicopter in question to this location, as will be discussed later.

The 2007 registration could have been a reuse of registration numbers made available when the previously assigned aircrafts were rendered inoperable, or retired from service.

The “new” HM12 can be seen, while still operational, in an undated and not geolocated picture posted in early 2016 by a user of Nairaland, a Nigerian-based online forum board:

On the same page, another apparent DRC helicopter, a Mi-8 registered as 9T-HM8, can be seen in photo on a previous posting.

Conclusions:

- 9T-HM12, a Mi-24 combat helicopter of Russian (post-Soviet) manufacturing, can be tracked as registered by the FAC since at least 2007;

- It appears possible that the helicopter was deployed at the Goma International Airport, before eventually crashing approximately 75 KMs away from that base on January 27, 2017.

The Pilots

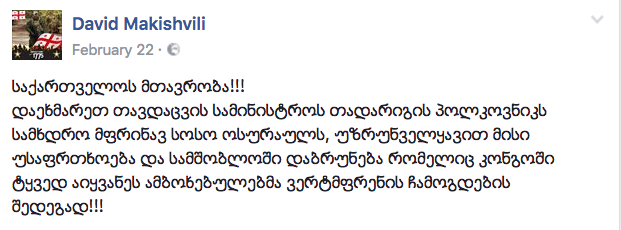

After several rumors about “Russian pilots” being involved in the two helicopter crashes, the Georgian Ministry of Defense (MoD) admitted that two Georgian citizens were involved as crew of one of the two aircrafts. First, on February 22, the retired Colonel of the Georgian Army David Makishvili published an appeal on his Facebook page to help “the Colonel and military pilot” Soso Osorauli being released from captivity:

Screenshot from the Feb 22 Facebook post by David Makishvili.

Then, on February 23, RIA Novosti published a report from the Georgian MoD confirming that one of the pilots had been taken captive, and naming him as “Сосо Осиураули” (Soso Osiurauli, though the surname will be later corrected in Georgian articles as “Osorauli”); also stating that a second pilot, still unnamed, was being treated in an hospital in Goma.

Finally, on February 27, the Georgian website Freedom And Democracy Watch reported that the second pilot had been named by the Georgian MoD as Vyacheslav Pluzhnikov. The article even included a picture of two caucasian men that could be both Pluzhnikov and Osorauli, among a group of possible children from the DRC, and two other men whose face had been blurred:

The article also stated the following:

“Pluzhnikov was arrested in 2010 in a case known as the Enver Affair, after an alleged Russian intelligence agent code named ‘Enver’. 15 people were arrested in the swoop, mainly air force officers. Those who pleaded guilty were soon released, but those who pleaded not guilty were sentenced to prison terms of various lengths. Pluzhnikov was among those who insisted on his innocence and he was sentenced for 13 years and 6 months. After the change of power in 2012, his case, which had previously caused much controversy, was reviewed. The following year, he was released in a mass amnesty following a prisoner abuse scandal.”

Finally, after a few months of silence, Georgian TV broadcasted a video (archived version) allegedly recorded by Osorauli’s kidnappers, and showing the pilot alive and in captivity, though shaken and possibly injured. The video is undated, and was rumored to have been produced to support a demand for a one million (US?) dollars ransom for the prisoner. A screenshot can be seen below.

Another undated image started circulating around the same time, which appears to show Osorauli with his possible kidnappers. The pilot seems to be wearing the same olive green uniform, and is covered with a blanket over his head:

None of the images acquired returned EXIF data useful to geolocate their capture, and nothing in the surrounding revealed more about the possible area where the images may have been taken.

Identities

Disclaimer: due to several of the identified actors not having been publicly named yet, and the fact that they are most likely still located in an active conflict area, we will obfuscate their identities in the following part of the research. An exception will be made for Osorauli and Pluzhnikov, whose names and pictures have already been widely distributed by the press and through social media.

Soso Osorauli

An initial open source research on Soso Osorauli brings back possible links to the 2008 Russian-Georgian War, which would not be unexpected for a military helicopter pilot on active duty. In addition to comments on him made by, again, retired Col. Makishvili, a 2014 article by a website called For.ge seems to associate a “Soso Osorauli”, a “Krokodili or Mi-24 pilot”, to the infamous 2007 Georgia helicopter incident that preceded the 2008 war. As the incident was widely attributed to the Russian military, it is possible that the article responded to a specific political agenda; nevertheless, it’s the earliest possible reference to Osorauli that we could track in public news.

A research of social media platforms leads to the discovery of a profile of interest on ok.ru, also known as Odnoklassniki, a social networking site particularly popular in the former Soviet countries, including Georgia.

The profile in question is named with a reference to the name “Soso”, and displays the profile picture of a man apparently intent at piloting an aircraft. The man’s appearance, claiming on his profile to be 41 years old, and located in Goma, DRC, seems to match one of the two individuals shown by the press in relation to the helicopter crash. According to the timestamp associated with the profile, his last login into ok.ru had been on January 27, 2017 — the day the incident happened.

Header of the located profile on ok.ru, with text translated from Georgian through Google Translate. Note the user-generated information on his location (Goma), and the automated timestamp applied by ok.ru to the last login (Jan 27).

Composite of the profile picture for the located ok.ru profile, and a photo of the possible Soso Osorauli distributed by dfwatch.net. Unfortunately, the resolution of the profile picture is too low to distinguish characters on the name tag.

The OK profile contains a trove of images that shed light on its owner. The first photo was posted on the account on May 13, 2015, possibly already from DRC; but even more conclusively, several images link what now clearly seems to be Soso Osorauli to FAC helicopters like the one crashed.

For example, in one photo posted on 28 December 2015, Soso is shown in front of a Mil Mi-8 helicopter with registration 9T-HM 5, therefore confirming registration within DRC:

Osorauli shown in front of a FARDC Mil Mi-8 helicopter registered as 9T-HM5. Note that the picture displays the December 28, 2015 date in Cyrillic script with identical format as some of the ones from the crash scene.

Another photo, also published by Georgian media in relation to the captive pilot, shows him in front of a Mil Mi-17 helicopter bearing the roundlet of the Georgian Air Force. While undated, it seems likely that it was taken before his relocation to DRC:

Mr. Osorauli can be geolocated in Goma in several of the photos posted on the ok.ru profile. For example, in an image posted on July 14, 2015, he’s shown in front of a known landmark of central Goma, the so-called “Chiduku monument”, celebrating one of the typical means of transportation for supplies in the region:

Another picture, posted on the same day and most likely taken in the same occasion, sees Osorauli standing in front of the Institut De Goma, a local university:

Overall, we can assess with moderate confidence that Soso Osorauli was located in Goma, North Kivu, since at least May 2015.

At the time of this writing, we could not locate other social media accounts associated to him.

Vyacheslav Pluzhnikov

The second pilot named in relation to the crash, apparently only injured and found recovering in a hospital in Goma, was Vyacheslav Pluzhnikov. Researching connections for Osorauli’s probable ok.ru account, we quickly located a profile named after a variation of Pluzhnikov’s full name.

His profile picture shows an individual strongly resembling the second man shown in the picture of the pilots as distributed by the press:

Composite of the profile picture for the ok.ru account possibly associated with Pluzhnikov (left), and the photo of the second pilot as distributed by the press (right).

Among his numerous posted photos, we can find several ones that depict the individual previously identified as Soso Osorauli:

Picture from Pluzhnikov’s ok.ru profile showing him (left) together with Soso Osorauli, and three unidentified individuals.

More importantly, one photo posted on July 24, 2015, depicts him and three more unidentified individuals in front of the Mi-24 helicopter registered as 9T-HM 12 — the one crashed in the North Kivu jungle. This is a key piece of information, placing Pluzhnikov, at the very least, in the same facilities where operations with such helicopters were run from.

Photo from Pluzhnikov’s ok.ru profile, showing him and three unidentified men in front of the 9T-HM12 Mi-24 helicopter from DRC

Crossing from ok.ru to Facebook, we are able to locate a profile named after another close permutation of his name. On it, together with the picture shown above, we can find Pluzhnikov posing next to Mr. Osorauli (plus two of the other unidentified men, and a couple of new individuals) in front of what is possibly the same helicopter. The picture was posted on Facebook on July 19, 2015.

Photo from Pluzhnikov’s Facebook profile, showing him, Soso Osorauli, and four unidentified men (plus one crouching) in front of a Mi-24 helicopter. Note that Pluzhnikov and two of the other men wear the same clothes as in the previous photo, possibly indicating that it was taken on the same occasion.

Those two pictures appear to be the first ones, in time succession, where Pluzhnikov can be located with good confidence in DRC – although a few ones from the Facebook profile, posted in June, could also have been taken in Goma or even Kinshasa.

Overall, we have placed the two pilots in DRC — most likely Goma — since May (Osorauli) and July 2015; we have linked them to the crashed helicopter; and we have discovered the presence of potential additional pilots from their same team.

In the next section, we will look at some of of those other individuals to acquire additional information on the Georgian PMC presence in Goma.

The Team

“The Trainer”

One individual that recurrently appears in photos apparently taken within DRC with either or both Osorauli and Pluzhnikov is a man claiming to be 60 years of age and from Tbilisi, with a name that appears very likely to be Georgian. We will call him “the Trainer”, owing to the reconstruction of his possible role within the PMC team.

The Trainer can be seen on several photos posted on Osorauli’s ok.ru profile together with the pilot:

Picture posted on 8 June 2015, and depicting the Trainer next to Soso Osorauli in what is likely to be a DRC location

The Trainer can be traced in Congo much earlier than Osorauli and Pluzhnikov. The earliest photo posted on his social media presences where he claims to be in DRC was posted in January 2014, and shows him in an helicopter’s cabin, next to what seems to be an FAC pilot:

Photo posted on the Trainer’s ok.ru profile on January 31, 2014, claimed to be taken in DRC, and showing him (left) next to a uniformed man sporting a DRC flag on his shoulder.

The Trainer consistently appears in association with a different Mi-24 helicopter than the one seen crashed – one that’s registered as 9T-HM5, and that we had observed earlier in this report. Multiple pictures show him in front of it:

Photo of the Trainer (red circle) next to Soso Osorauli and in front of the 9T-HM5 helicopter

The role of this individual as a trainer is suggested by the content of his pictures on both ok.ru and a Facebook profile with his same name — most of which contain different people in a pilot uniform, often showing a DRC flag. Additionally, one comment left in French by a contact on his Facebook profile in January 2016 clearly mentions an “M7 training flight”, congratulating with the Trainer for it:

Finally, and most importantly, the Trainer seems to receive an institutional treatment by the FARDC/FAC. A picture posted on his Facebook profile in March 2016 shows him on board of a minivan, flanked by a uniformed man who appears to be a Sergeant Major of the FAC, judging from his insignia, including the collar pins. The minivan sports both the Georgian and DRC flags, in what could have been a formal welcoming to the Trainer and/or his team.

2016 photo of the Trainer with a FAC official, and the Georgian and DRC flags on his minivan

Other Pilots And Trainers

A small group of other individuals recurrently appears in photos as associated to Osorauli, Pluzhnikov, and/or the Trainer. Their uniforms, poses, and location of the pictures suggest that they may also be either pilots, or in at least one occasion, trainers. For all those whose social media presence was determined, names and posted content link back to Georgia.

A few photos include:

Undated picture showing the Trainer (red) and another probable Georgian trainer (yellow) in his 60s, together with a few DRC pilots or officials

Another photo showing the Trainer, the possible colleague, and a group of probable local pilots or crews in DRC

In total, another three people were determined as consistently or sporadically appearing in photos within DRC with either Osorauli, Pluzhnikov, or the Trainer. Given their apparent younger age, they could be pilots, or junior trainers.

Why Were They There?

Affiliation

On February 1, 2017, the commander for the Third Military Region of the FARDC, General Leon Mushalé, conducted a press conference about the helicopters’ crash in which he declared that “the [helicopters’] manufacturer provided the services of ‘a trainer’”, without specifying his or her nationality.

The manufacturer of the Mil Mi-24 helicopters is the Mil Moscow Helicopter Plant, owned by the parent company Russian Helicopters. While an entire ecosystem of job offers for Mi-24 pilots, both in Russia and abroad, exists on web forums such as Aviaforum.ru and similar ones, we could not locate job postings that could match the deployment of any of the identified individuals.

Attempts to obtain clues of the pilots or trainers affiliation via their uniform or insignia were also unsuccessful. Both Mr. Osorauli and the Trainer, for example, are often seen in photos while wearing a badge with a blue lanyard. Unfortunately, the resolution of those pictures is too low to read the information on the badge.

Composite of a photo of the Trainer and a previously seen one with Osorauli, both wearing a similar white badge with blue lanyard.

It is worth to note, however, that several photos showing members of the UN peacekeeping mission MONUSCO (or, previously, MONUC) while at the Goma International Airport show them wearing a different type of badge. This appears to confirm that there was no affiliation between the Georgian pilots and MONUSCO.

MONUSCO mission member wearing her badge while at Goma International Airport in a photo posted in 2015. The badge is visibly different from that worn by the Georgian pilots.

While we can confidently rule out that the Georgians were in any way linked to the UN mission, two alternative options remain open:

- That the Georgians were employed by Russian Helicopters or one of its subsidiaries to provide training to FARDC pilots in Goma;

- That they were contracted by one of the many private military companies active in DRC, in which case their role could have extended beyond the delivery of training, and included active combat support.

At this time, and with the available gathered evidence, neither of the options can be confirmed or dismissed.

Political And Military Instability

To find clues for the motive behind the presence of foreign trainers to the FARDC in Goma, it is useful to look at the recent history of the North Kivu region, as well as to the information gathered on the pilots’ presence in DRC.

As previously shown, we can track Osorauli and Pluzhnikov, the two pilots allegedly involved in the crash of 9T-HM12, as in DRC since at least mid-2015. No earlier evidence of them being in Goma or other DRC locations prior to that period was found; on the contrary, they had been posting photos and other references to Georgia in the previous months.

However, the Trainer was geolocated to Goma as early as January 2014, an entire 15/18 months before the two pilots did. Other Georgian individuals, probable pilots and/or trainers, were found with the Trainer in his earliers DRC presence, though some of them seem to relocate in later months, judging from social media content that we were able to locate.

Goma had been at the epicenter of the M23 “rebellion” officially until November 2013, when it announced the end of the offensive, and its disarmament. Since then, however, more or less sporadic skirmishes or full-fledge clashes with the militia have continued in the province’s forested areas, according to multiple reports.

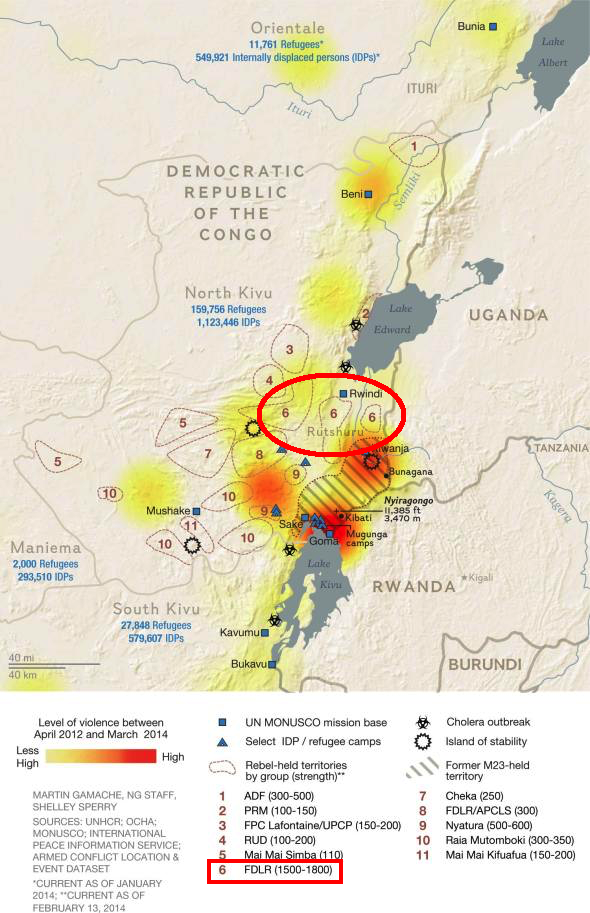

In parallel to that, and particularly after M23 “disarmed”, a Hutu armed group known as the FDLR has ramped up operations in North Kivu, taking control of areas north of Goma – including Rutshuru, where 9T-HM12 reportedly crashed.

In March 2014, therefore shortly after the initial geolocation of the Trainer in Goma, the National Geographic published a detailed map of the eastern Congo violence between since April 2012. The map shows how the FDLR was controlling a strip of land east and west of Rutshuru, in addition to the town and its surroundings:

Map released by the National Geographic, showing the distribution of violence events in eastern DRC between Apr 2012/Mar 2014. The FDLR is shown as the militia controlling the area surrounding Rutshuru.

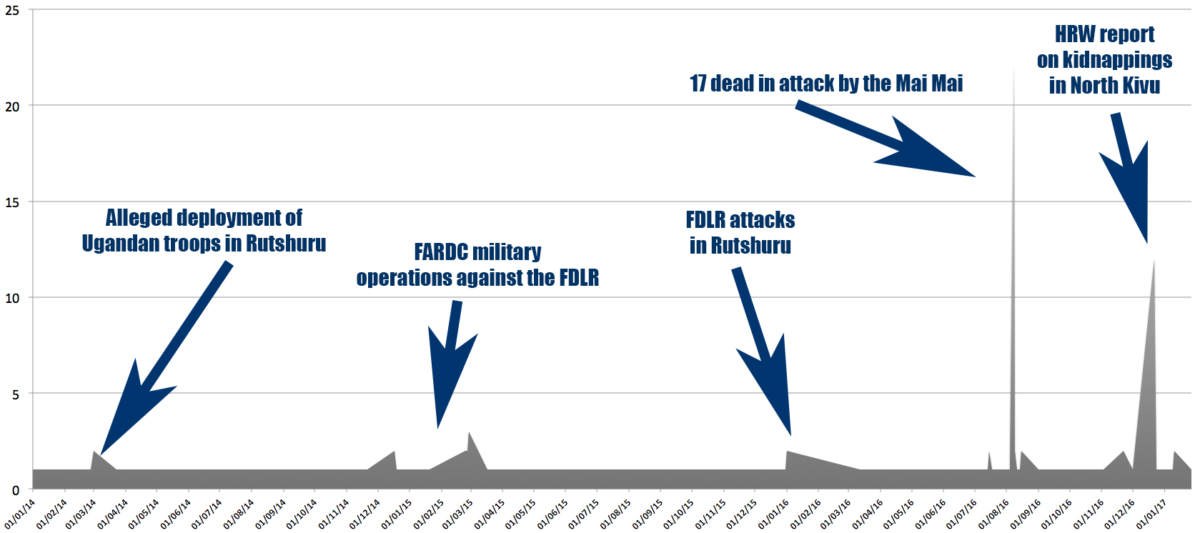

An examination of the local, national, and global press reports mentioning Rutshuru in relation to military events, between January 2014 (when the Trainer was first placed in Goma) and January 2017 (when 9T-HM12 crashed in the area) paints a picture of continued violence, attributable to different militias, and to the FARDC counteroffensive:

Timeline of press reporting on military/violence events in Rutshuru, North Kivu. The Y axis represents the amount of press reports tracked for each event.

Attacks to the local population, ambushes aimed at FARDC soldiers, and related FARDC counteroffensives populated the three-year timeline consistently. Reporting increased since mid 2016 and through early 2017. However, this does not mean that violence had also increased, but that press attention had focused on the region more over time.

FARDC Ineffectiveness

Such a timeline also tells a story of inability by the FARDC, even over the space of only three years, to contain and mitigate multiple rebel militias, and their continued attacks to the area north of Goma.

The issue goes far back in time. In 2009, for example, Human Rights Watch detailed cases of mass murder and sexual abuse committed by the FARDC in North Kivu in a scathing investigative report.

The FARDC troops, beside often completely lacking training and military expertise of any kind, have little incentive to protect the population, which they regularly loot, since they barely get paid. And it appears significant, although not unique, that in some occasions, military attacks in Rutshuru found the Republican Guard, Joseph Kabila’s pretorians and an elite force, to be a target. Their deployment is usually associated with strategic locations having high significance for the central government in Kinshasa.

In 2013, MONUSCO, the United Nations mission in DRC, added an offensive component to its mandate with resolution 2098. As stated on the UN website:

“On 28 March 2013, faced with recurrent waves of conflict in eastern DRC threatening the overall stability and development of the country and wider Great Lakes region, the Security Council decided, by its resolution 2098, to create a specialized “intervention brigade” for an initial period of one year and within the authorized MONUSCO troop ceiling of 19,815. It would consist of three infantry battalions, one artillery and one special force and reconnaissance company and operate under direct command of the MONUSCO Force Commander, with the responsibility of neutralizing armed groups and the objective of contributing to reducing the threat posed by armed groups to state authority and civilian security in eastern DRC and to make space for stabilization activities.”

While not openly stated, this can be considered as a clear recognition of the inability by the FARDC to independently secure and stabilize the region.

MONUSCO went on to engage with M23 fighters in several occasions — typically, though its combat helicopters, as they were already doing since at least 2012.

Natural Resources and Mining

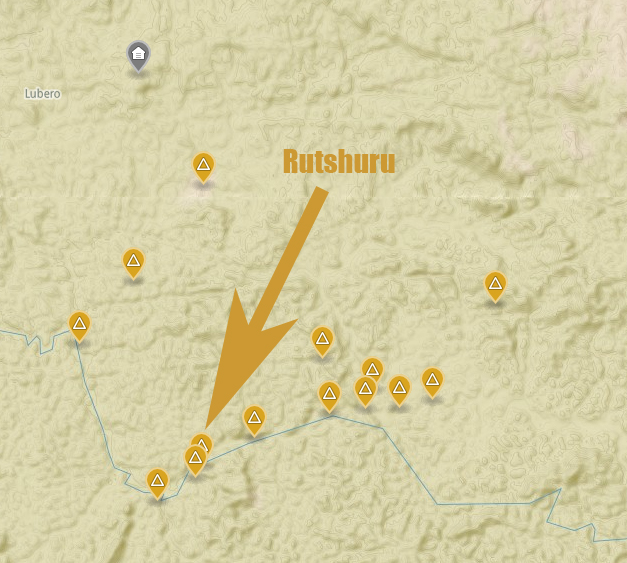

The strategic significance of the Rutshuru and, more broadly, the North Kivu areas is evident when looking at the distribution of natural resources and mining in the region. The International Peace Information Service (IPIS) has conducted extensive research on mining in the DRC, and made available on their website an interactive map of mining locations.

Rutshuru, and the surrounding region within North Kivu, is home to some 15 gold mining sites, which can easily explain the focus of multiple rebel groups — and of the FARDC — on securing control of the area.

North Kivu – Map of gold mines around Rutshuru (source)

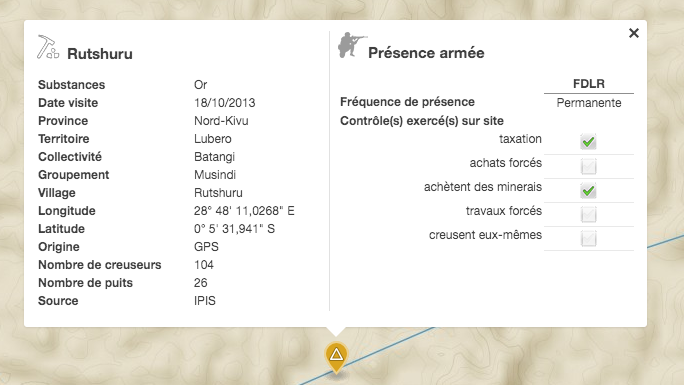

In October 2013, the village of Rutshuru and a related gold mine were recorded by the IPIS as under permanent control by the FDLR, which both exercised taxation on the extraction of the mineral and was directly involved into its trafficking to the end markets:

(Source)

However, the real significance of Rutshuru on the mining landscape was detailed even further by an article originally published on Zmag. The article singles out Rutshuru’s mine — called Lueshe -— and the reason for its importance:

“As valuable as the mine in Bisie is, the Lueshe mine located in Rutshuru Territory (North Kivu Province) may be even more valuable. The mine contains an extremely valuable deposit of pyrochlore. The chemical composition of this ore is so unique; numerous chemistry reference manuals give it its own name: “Lueshite.” The only other place pyrochlore can be extracted from is Araxá, Brazil. The village is located on a mining concession owned by the Société Minière du Kivu (SOMIKIVU).

[…]

Pyrochlore is a radioactive compound comprised of a niobium compound bound to a form of tantalum called a microlite. The niobium (also known as columbium) is currently more desirable than its sister component. It is primarily used to create heat-resistant steel and glass alloys used in various construction materials. The steel alloys are widely used to construct oil pipelines and the glass alloys are used in the corrective lenses of eyeglasses. Niobium is also used in nuclear reactors, air frames, jewelry, chemical processing equipment, magnetic resonance imagery (MRI) machines and superconducting magnets. When niobium is combined with iron, the super-alloy ferroniobium is formed, which is used in jet engines, rocket assembly, furnace parts, automobile and truck bodies, railroad tracks, ship hulls, and turbines depending on the percentage of niobium composition.”

The Lueshe mine is tracked on Google Maps at this location. The link comes with several user-uploaded pictures of the facilities dating back to 2005. Two-year old satellite imagery show such facilities in detail, giving a clear impression of a very much active mining site:

Lueshe mine in 2015. Source: DigitalGlobe via Google Earth, enhanced in Photoshop.

Conclusions

It was not possible to locate a “smoking gun”, the definitive proof of the reason why former military pilots from Georgia would be onboard of FARDC combat helicopters in North Kivu, together with FARDC members, during a mission over an active conflict area. However, observing the timeline of the located open source content, as well as the general security, political, and extractive environment in the area over the past few years, it appears reasonable to confirm that Georgian experts were hired to train FARDC pilots in counterinsurgency operations.

It is equally not possible to conclusively state that such pilots were involved in combat operations when the incident happened, or at any other point in time while in DRC. However, it does appear highly suspicious that at least one Georgian pilot with extensive combat expertise, Soso Osorauli, was piloting (or aboard) one of such helicopters.

No evidence of affiliation with the MONUSCO operations under UNSC resolution 2098 was located, despite the pilots clearly operating from the same facilities – most notably, Goma International Airport.

North Kivu remains an area of endemic instability due to multiple factors, each of which is linked to the richness of the extractive industry in the area. It’s not surprising that capabilities of a very lacking national armed force would be sought to increase through the use of international security and military experts available on the private contractors market. An entry on the DRC Air Force on Wikipedia, even states, without linking to any sources, that “foreign private military companies have reportedly been contracted to provide the DRC’s aerial reconnaissance capability using small propeller aircraft fitted with sophisticated equipment.”.

That such a partnership — or direct hiring — involves private military contractors utilizing government assets such as FARDC combat (therefore, with offensive capabilities) helicopters remains peculiar, and previously unreported in the area.