Houthi-Controlled Port Receives Vessel from Occupied Crimea After UN Inspection Body Grants Clearance

This article is the result of a joint investigation by Bellingcat and Lloyd’s List. The Lloyd’s List version of this piece can be found here.

A Russian flagged vessel was granted clearance by a UN inspection body to call at a Houthi-controlled port after surreptitiously exporting grain from a western sanctioned terminal in occupied Crimea, an investigation by Bellingcat and Lloyd’s List has found.

The bulk carrier, Zafar (IMO: 9720263), switched off its Automated Identification System (AIS) – that allows it to be tracked by shipping services and which commercial vessels are mandated to keep on unless in danger – when it visited the Port of Sevastopol in May this year.

Satellite imagery revealed the vessel’s presence at the port.

Zafar then switched AIS on after leaving Sevastopol and kept it on for its journey to Yemen, according to Lloyd’s List Intelligence data. It docked in Djibouti in late June where it was given clearance by the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM).

It is not clear if UNVIM knew that the shipment had come from occupied Crimea given Zafar sought to mask the fact it went there.

While there is no suggested illegality with this shipment, experts say it creates an awkward situation where a UN mechanism has waved through a grain shipment from occupied Ukrainian territory despite Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine and the fact that member nations have repeatedly voted against Russia’s actions towards its neighbour.

The UN General Assembly has passed a number of resolutions against Russia’s invasion of Crimea and eastern Ukraine dating as far back as 2014. It also demanded Russia withdraw all military forces from Ukrainian territory following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. But unlike some resolutions from the Security Council, on which Russia sits and has a veto, General Assembly votes are not legally binding.

The Port of Sevastopol is currently under United States and United Kingdom sanctions, while the terminal that Zafar docked in at Sevastopol is under European Union sanctions.

Importantly, however, there are no UN sanctions on the Port of Sevastopol or Russia.

Daniel Martin, a partner at the Holman Fenwick Willan law firm who specialises in international trade sanctions told Lloyd’s List: “[if] you look at this from the perspective of the global policy objectives of getting food into Yemen and preventing the entry of arms then UNVIM is fulfilling its mandate.”

“But if you look at the bigger picture, then it is likely that western countries would prefer that this happens without enriching sanctioned countries,” he added.

Material on the UNVIM website outlines that it has received “voluntary contributions and active support” from the likes of the EU, US Department of State, USAID and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the Netherlands since it was set up in 2015.

It was not clear exactly where the grain carried by Zafar to Yemen was harvested, but some farmers in occupied eastern Ukraine have previously accused Russian forces of stealing grain that was subsequently exported.

Yemen is one of the world’s poorest countries. The decade-long civil war between the Saudi-backed internationally recognised government and Iranian-backed Houthi forces has led to thousands of deaths and a humanitarian crisis. The UNHCR states millions have been displaced and there is a risk of widespread famine.

UNVIM facilitates the movement of commercial items to Yemeni ports not under the government’s control, while also ensuring compliance with a UN arms embargo. As of 2018, UNVIM grants clearance for the Houthi-controlled ports of Hodeidah and Saleef (also known as As-Salif).

Merchant ships are required to submit a clearance request with supporting documentation, such as bills of lading and clearance from load port, to UNVIM prior to their arrival. Provided there are no issues UNVIM will grant clearance. If there are any suspicions regarding the ship’s movements, crew, documents, or prohibited cargo on board then UNVIM will inspect the ship.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs confirmed to Lloyd’s List that Zafar did indeed report to UNVIM for inspection and was cleared on June 21, with a certificate following on June 22, 2024. It said it was then up to the Saudi-led EHOC to make the final decision to grant clearance to Zafar based on UNVIM’s inspection report.

OCHA declined to provide further information about Zafar including whether the port of loading was known to be Sevastopol at the time of clearance being approved and if the vessel was physically inspected. The Saudi Ministry of Defence did not respond to emailed questions from Lloyd’s List before publication.

Russia has been explicit about its goal to expand its grain exports – at the expense of Ukrainian grain exports – in order to win foreign influence and goodwill. The country’s President, Vladimir Putin stated in 2023 that Russia had “the capacity to replace Ukrainian grain, both commercially and as free aid to needy countries.”

Zafar arrived in Saleef just a couple of days before a visit of a Houthi delegation to Moscow in early July where issues including Yemen’s Civil War were discussed.

The Russian government and Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to emailed questions about the shipment before publication, nor did the operator of Zafar.

When approached for comment, the US State Department referred Lloyd’s List to UNVIM in regards to this specific incident but reaffirmed its support for the work of the agency.

Tracking Zafar’s Trip to Yemen

In December last year, Zafar was observed by Bellingcat and Lloyd’s List delivering grain loaded at the Port of Sevastopol to Bandar-e Emam Khomeini in southern Iran, thus making it a vessel of interest.

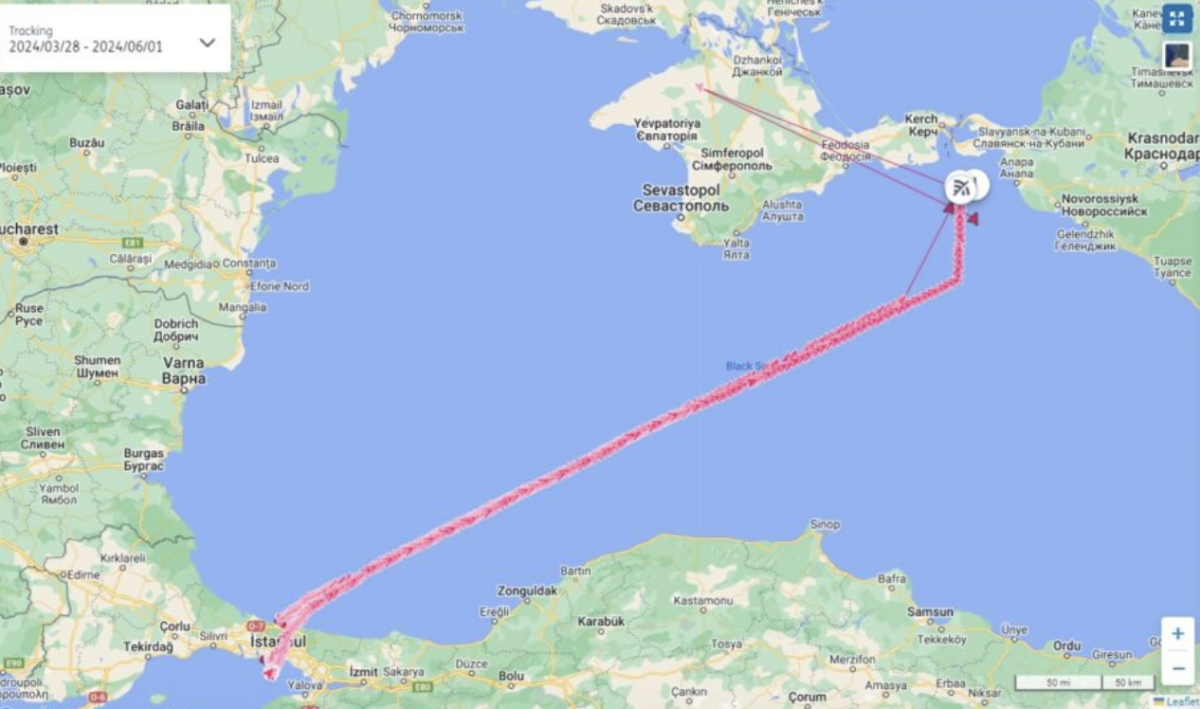

It was visible on AIS data in the Kerch Strait, a narrow body of water between occupied Crimea and mainland Russia, from mid-March until March 30.

Yet at this point it sent tracking data intermittently, disappearing on April 13.

This has been common practice for ships visiting the Port of Sevastopol ever since western sanctions were introduced in 2015, and especially since the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 – as the below graphic detailing ships that visited Sevastopol with AIS off but which were captured on satellite imagery in just the first year of Russia’s full scale invasion emphasises.

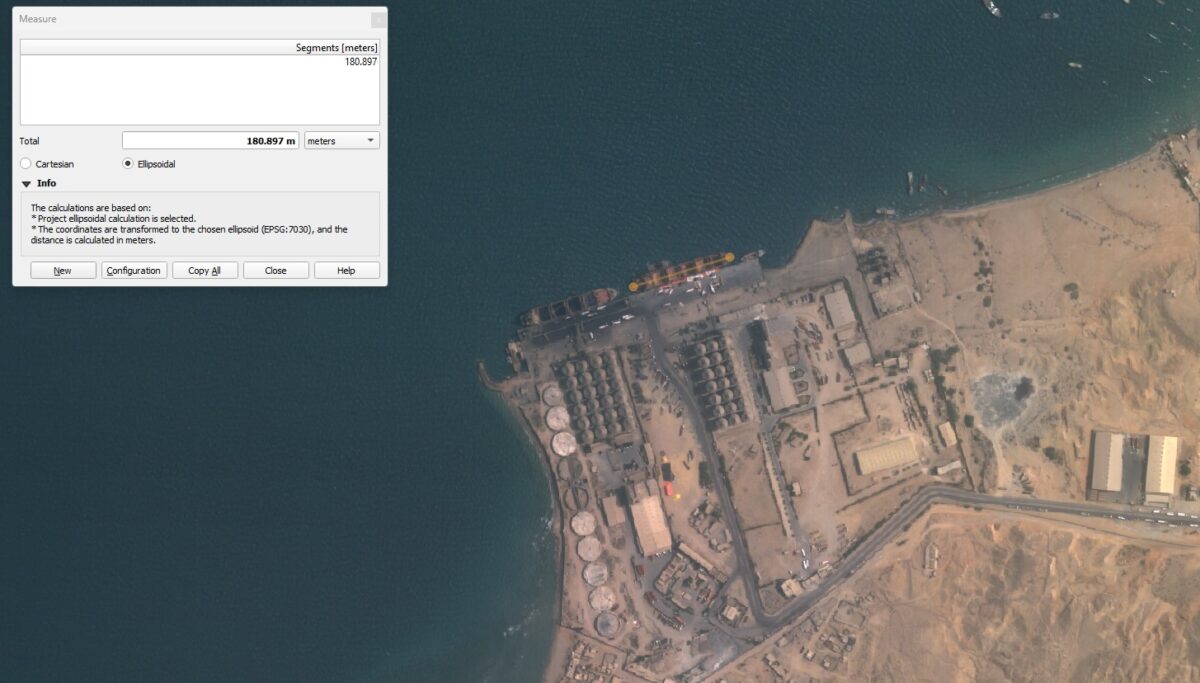

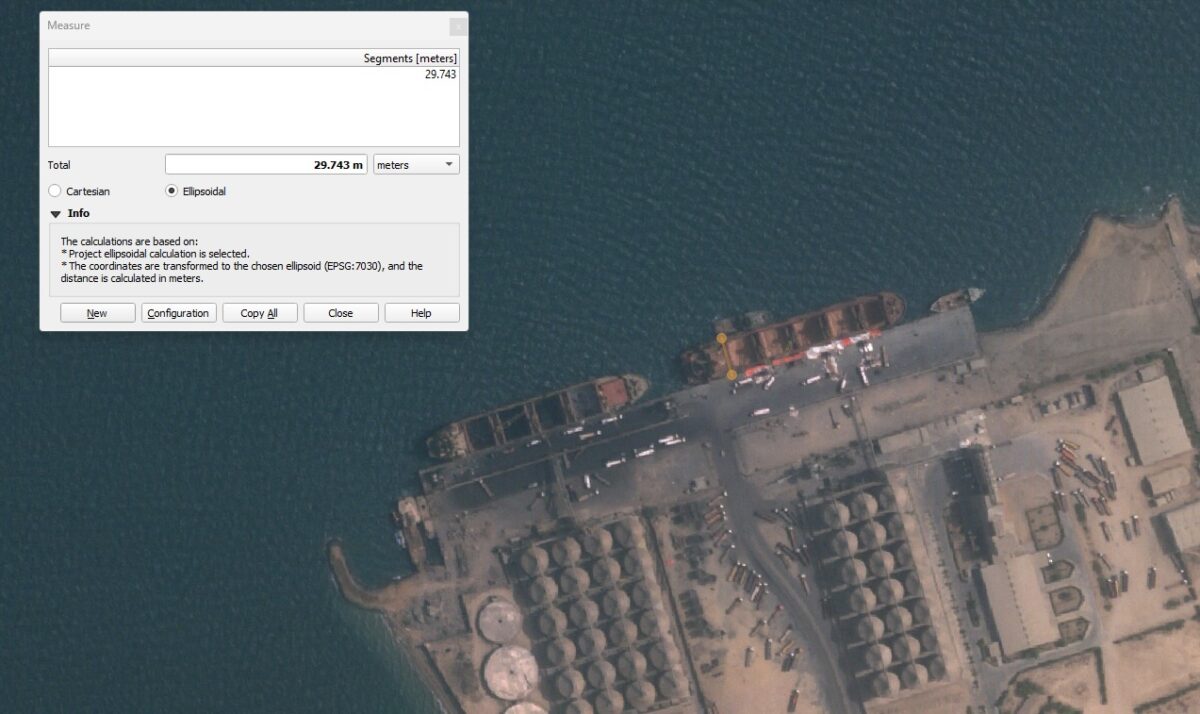

Satellite images taken between mid-May and late-May 2024 indeed appear to show Zafar docked in the Port of Sevastopol.

As well as an image from May 17, another image from May 24 appears to match the measurements and unique specifications of Zafar such as the yellow cranes as well as its distinct chimney and bridge.

A comparison with an image gathered during a previous investigation emphasises these similarities.

Upon leaving Sevastopol, Zafar began broadcasting AIS once more while safely back in the area south of the Kerch Strait where AIS signals had previously ceased. Without the assistance of satellite imagery, it would have appeared to have remained in this area.

It transited the Bosphorus Strait on June 1, with photos from the ground matching AIS data documenting Zafar’s movements.

These images also highlight the unique features of the ship that were visible in satellite images from Sevastopol such as the yellow cranes, chimney, bridge and position of the lifeboats.

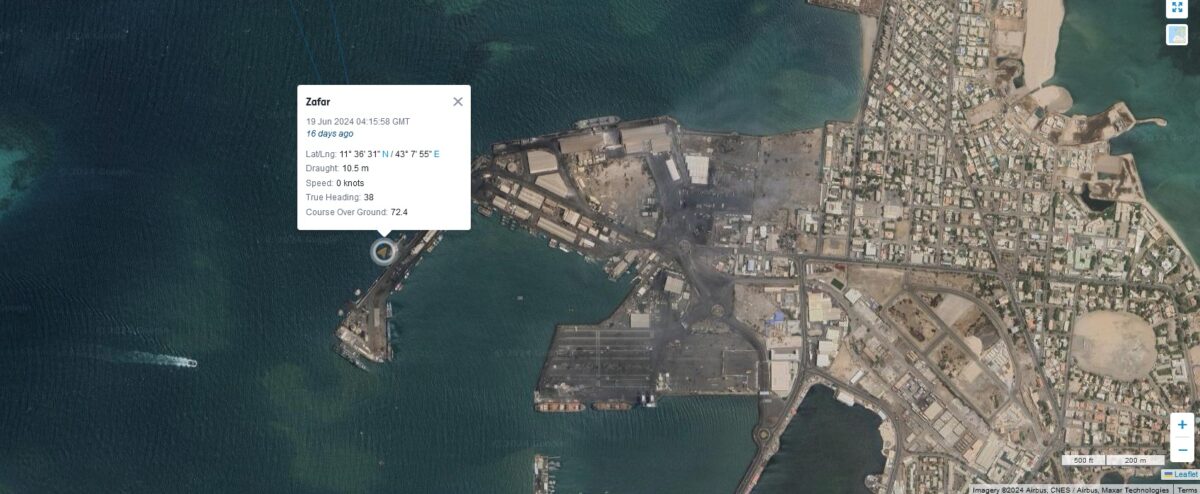

Zafar could be tracked by AIS all the way through the Mediterranean, on to the Suez Canal and the Red Sea before arriving in Djibouti on June 16. It stayed in anchor just off shore before docking on June 19.

After its port call in Djibouti, Zafar sailed to Saleef, in Yemen. It spent another few days anchored off the coast there before docking at the Saleef Port on June 30.

AIS data showed the ship’s position while satellite images show a ship with the same dimensions and same features as Zafar.

Interestingly, the compartments are open and appear to have been emptied. Trucks can be seen lined up alongside the vessel while at least one crane appears to be hovering over structures on the pier.

At time of writing, Zafar remains docked at Saleef. It could be seen there in satellite imagery and on AIS tracking data.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here and Mastodon here.