A Phantom’s Tale: The Coyote Influencer on TikTok

An alleged coyote holding a walkie talkie crouches by some mangroves. In another video, he speaks to the camera about the fact that new floating barriers deployed in the Rio Bravo/Rio Grande won’t stop him crossing the river.

The only problem – we geolocated this footage to a Marina south of Miami, Florida, almost 2,000 km away from that river on the US-Mexico border.

Bellingcat and our investigative partner the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) analysed his TikTok account of 150,000 followers which alluded to people smuggling activities via hundreds of videos and posts. Scores of people requested information about being smuggled or working as a smuggler, but we found many of the account’s claims don’t add up. Experts told us the account portrays a cartoonish version of real life smuggling.

Bellingcat contacted the account holder – a man who goes by the name Maldonado- and in an unexpected turn, he claimed to help people cross the US-Mexico border undetected without charging them and without receiving permission from organised crime groups.

But we couldn’t confirm these claims. It was not clear who was really behind the account and whether it acted as a marketplace for smuggling activities or was simply a scam.

Maldonado’s account was banned by TikTok after we contacted them about it.

A TikTok Spokesperson told us:

“We have zero tolerance for content that facilitates human smuggling. We continue to work closely with law enforcement and industry partners to find and remove content of this nature.”

The Economics of Illegal Migrant Smuggling in Central America

Maldonado’s account stood out from dozens of TikTok accounts that Bellingcat and CLIP reviewed which promoted people smuggling services, depicting a trouble-free journey for people moving through Central America into the US. You can read their investigation here.

We surveyed approximately 100 advertisements on TikTok offering smuggling services.

The smuggling of Latin American migrants into the United States is a multi million dollar operation. It has been reported that more than two million migrants were apprehended at the US border in 2022 and 2023.

Depending on the point of origin and package selected, migrants are reportedly charged between USD$2,000–10,000 to be smuggled into the US.

According to the International Organization for Migration (OIM), while a VIP service includes air travel and accommodation in hotels and costs up to USD$60,000, the most basic service includes crossing into the US by inflatable boat, walking, or confined in trucks.

The basic structure of the migrant smuggling networks includes the leader of the smuggling network, followed by the Coyote or Pollero and the Enganchadores.

Coyotes or Polleros guide migrants during the journey – they are in charge of all tasks related to the illegal crossing.

Enganchadores or “recruiters” are responsible for recruiting migrants to make the journey – often people are recruited in person in transport hubs; but also increasingly online.

Migrants reportedly have to pay a chain of stakeholders which ranges from small local recruiters and smugglers. Drug cartels typically used to charge smugglers a toll fee for each migrant crossing their territories but their active participation in the business is reported to be increasing due to the larger number of migrants seeking to cross.

US border states such as Texas have been responsible for increasing militarisation of the US-Mexico border and human rights groups have identified persistent human rights abuses by US customs and border police. Bellingcat has previously written about US nativist militias that have been deploying aggressive anti-immigrant tactics, and have even crossed into Mexican territory during ‘patrols’ .

The Digital Coyote

Created in February 2023, Maldonado’s account featured hundreds of short clips showing a mixture of people smuggling operations, small aircrafts and semi-trailers.

We reviewed a thousand posts on the account, which started to reveal a pattern.

In some videos Maldonado is featured on camera, he is seen wearing vaguely camouflage clothes often with a walkie talkie and the audio accompanying these clips often involves discussion of smuggling activities. Mixed in with these posts there are personal posts – of horse riding or other activities such as quad biking. Dozens of videos feature people in camouflage walking in the desert, a field or by a river bank. Crucially, none of these videos feature Maldonado on camera.

We identified approximately 50 videos where Maldonado filmed himself sitting near a body of water with a walkie talkie. In some of them he implies the body of water is the Rio Bravo by adding background music or location pins.

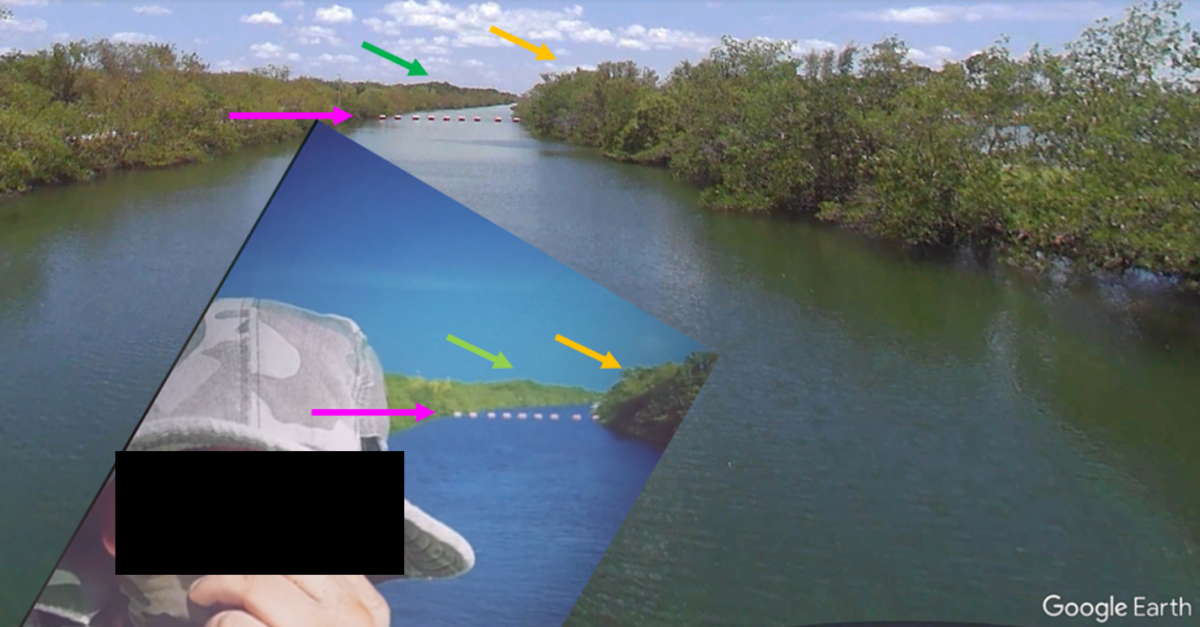

At first glance, we noticed the swampy mangroves of the river banks featured in his videos, which do not match the vegetation seen in the semi-arid climate of the US-Mexico border region. Notably, mangroves are a feature of coastal wetlands, found in tropical and sub-tropical environments.

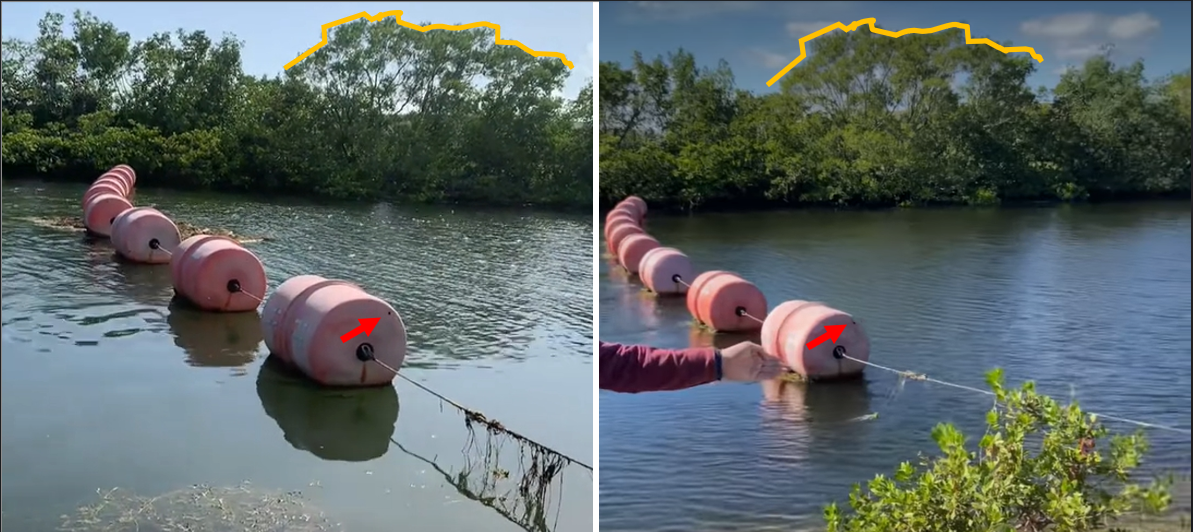

In July 2023, the state of Texas began installing a floating barrier along the banks of the Rio Bravo river in order to deter migrants from crossing into the United States.

In September of that same year, Maldonado posted a video showing a ‘floating barrier’ in a river stating that it would not stop him from crossing it. The video has been viewed 250,000 times.

However, rather than showing any ‘border barrier’ installed in the Rio Bravo, we geolocated it to Black Point Marina in Florida described on Google Maps as a “waterfront hangout featuring a dockside eatery, picnic pavilion, fishing jetty & jogging trail.”

The Marina is about 2,000 km away from Rio Bravo and the US-Mexico border.

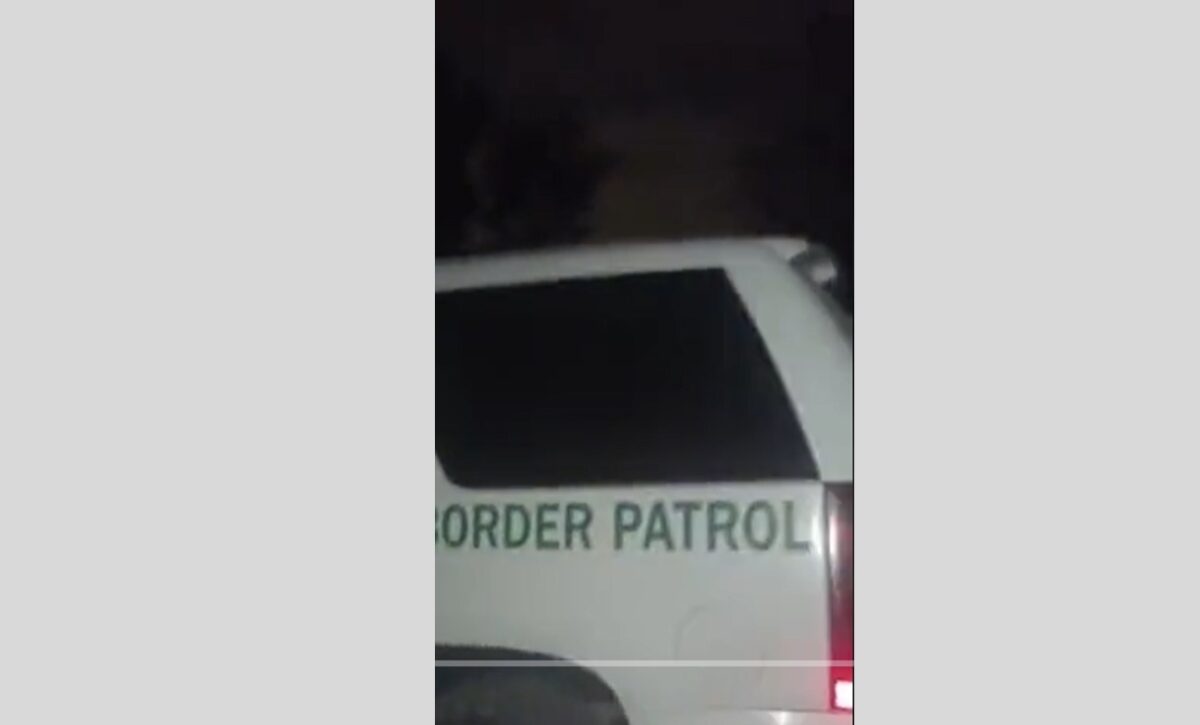

Another video shows a close up of what appears to be a US border patrol vehicle filmed at night. The car is empty. Two voices can be heard apparently speaking in a radio transmission. We found that the radio communication audio matches this YouTube track published nine years ago.

Superior Service and Allusions to Narcoculture

In a pinned video, Maldonado personally asked people to contact him via video call if they want more information. Hundreds of people commented on his videos asking for more information about being smuggled into the United States.

Maldonado repeatedly claimed that his crossings are more expensive but more successful than others.

For instance, in videos showing migrants being detained by border police, an overlayed text implies that although he charges more, those who charge less are not as safe or efficient.

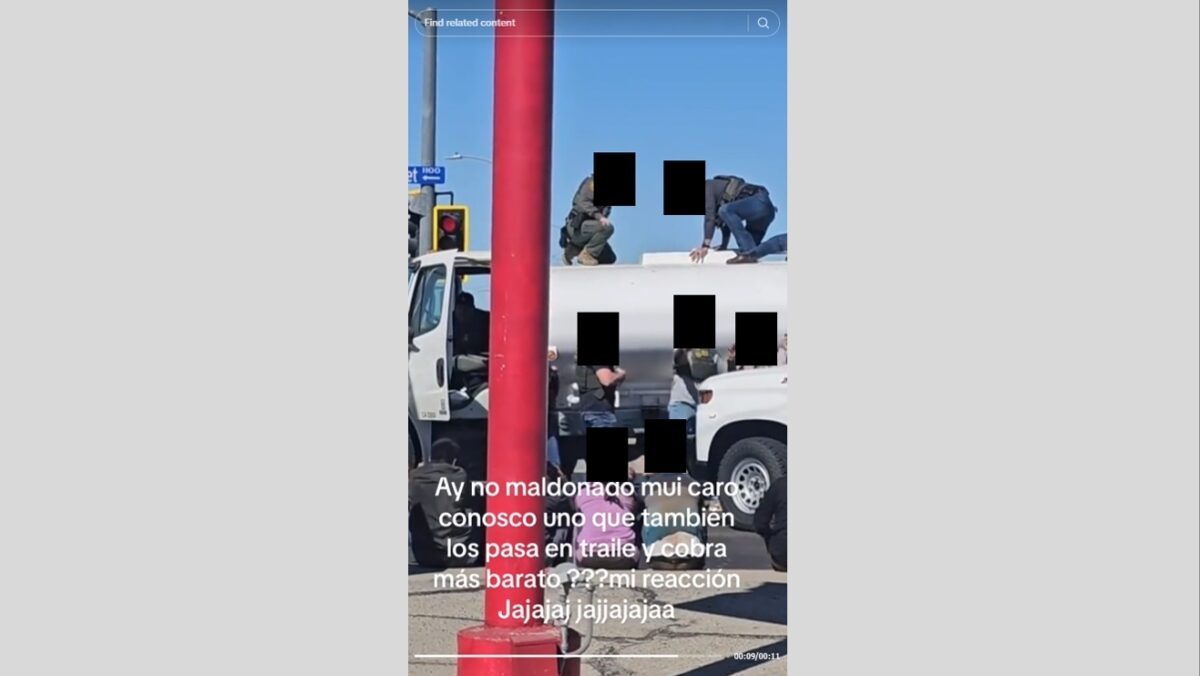

One post reads:

“Hey Maldonado, you’re too expensive. I know someone who also crosses in trailers and charges less.” Maldonado then continues with a text saying: “My reaction: hahahahaha”

A Note On Narcoculture

Mexico’s drug war has reportedly penetrated the social fabric of the nation influencing language, music and even religion. This social phenomenon called narcoculture extends through other regions in Latin America affected by the violence of drug trade.

The luxury and out-of-the-ordinary life of drug traffickers has given way to a fascination among the public. This fascination allegedly helps cartels to attract and recruit younger generations.

According to a study carried out by the University of Nayarit, narcoculture influences young people who are seeking to escape poverty and achieve social recognition.

The New York Times has also reported on a genre of videos on TikTok depicting drug trafficking groups and their activities.

In 2022, Milenio reported on a series of viral videos on TikTok from alleged members of narcotraffic groups showing their lifestyle, daily work, weapons and alleged connections with drug cartels.

“Narcocorridos” or drug ballads are an important part of narcoculture and their lyrics attempt to glorify drug cartels.

Although never seen carrying a gun in his TikTok videos, in at least three of them Maldonado repeats the following message: “Tell the teacher I couldn’t join the class because I am working now for La Chapiza.” Several people then comment on the videos asking for a job opportunity.

The same phrase repeated by Maldonado became viral two years earlier in a video posted by alleged members of “La Chapiza”, a term associated with armed men serving the sons of former Sinaloa cartel Leader Joaquin Guzman Loera, also known as “El Chapo”.

In another post, footage shows someone driving along a motorway with a caption that reads:

“In short, do you ask La Maña for permission?”

The car then drives by a group of parked pickup trucks. “La Maña” is a colloquial term in Mexican-Spanish for organised crime but it is also associated with specific organisations reportedly linked to the Sinaloa Cartel.

“Everyday I traffic people…”

One element that made Maldonado’s TikTok account stand out from other digital coyotes is the careful reinforcement of his narrative through bespoke “corrido” music.

Mexican corridos originated in the early 1900s and are very popular on both sides of the US-Mexico border. Since corridos are centred on themes important to the populace, they are deeply influenced by developments along the border.

Some controversial subgenres (like narcocorridos) are associated with narcoculture. Their lyrics are often compared to gangster rap.

In 2023, a singer released a corrido song apparently dedicated to Maldonado. The song summarises Maldonado’s alleged biography and his origins in Honduras as well as some details of his alleged smuggling services.

One line in the song begins: “Everyday I traffic people…”

The song is hosted on YouTube, Spotify and Apple Music.

Another song dedicated to Maldonado makes reference to his apparent smuggling service run between Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico and the US.

A section of the song is dedicated to his alleged semi- trailer truck operation and ‘immunity’ or sponsorship when they cross the border.

The lyrics include:

“A new route, the lorries move ahead loaded

They crossed the line [border], very well protected.….

…..They depart from Reynosa bound for the other side…”

The image accompanying the song shows an AI generated illustration of a semi-trailer truck crossing a checkpoint with what appears to be the Mexican and US flags on either side of the crossing.

Maldonado posted testimonial videos of alleged migrants travelling inside the cabin or sleeper of semi-trailer trucks, but not in the trailers themselves.

Semi-trailers or lorries have been used to smuggle many migrants across Mexico and the US-Mexico border, sometimes with fatal consequences. In March 2022, a heavily pregnant woman from Nicaragua died after being left abandoned with 160 other migrants inside the cargo space of a semi-trailer in Monclova, Coahuila, Mexico. A few months later, in June, 53 people died after being trapped in a trailer truck found near Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. Our partners CLIP and an alliance of Latin American outlets have reported on migrant trailers in more detail, here.

A Real Coyote, an Influencer or Just a Con?

The real purpose behind Maldonado’s account remains unclear.

Bellingcat contacted TikTok to ask about our findings. After we reached out to them Maldonado’s account was banned for violating TikTok guidelines. TikTok reviewed other ads we identified and said they removed those which violated their guidelines. TikTok told us that it prohibits content that facilitates human smuggling and trafficking, pointing us to their Community Guidelines. TikTok told us that in 2023 they launched a number of search interventions to alert its community to the risks of human smuggling and trafficking, so far this has been rolled out across countries in Europe. TikTok told us that content moderation at scale requires constant improvement of policies and enforcement strategies.

We showed Maldonado’s account to Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, Professor at George Mason University and expert in organised crime, immigration, border security, social movements and human trafficking.

She told us that TikTok posts about smuggling operations exploded after Title 42 was introduced by former US President Trump in 2020, allowing US border officials to turn away migrants on the grounds of preventing the spread of Covid-19. Regardless of their true purpose, many of the posts on TikTok create a sense of urgency about migrant crossing, promoting an attitude that the opportunity to cross into the United States is ‘now or never’, Correa-Cabrera said.

“As with any other economic activity the utilisation of social media is fundamental.”

Correa-Cabrera said that it was “absolutely” the case that Maldonado’s account was designed to give the impression that he is involved in people smuggling and that there appears to be a well thought out strategy behind the account.

“This appears to be a deliberate consistent message repeated again and again. That he is involved in people smuggling, that this is what people smugglers do.”

“There are a lot of resources behind that account.”

However the purpose of the account was less clear, Correa-Cabrera said. One hypothesis is that it acts as a marketplace that connects different actors involved in smuggling, using traits of influencer culture to recruit and advertise.

Alternatively it could indeed be offering smuggling services, or maybe it has a political motivation or is simply a scam.

But ultimately smugglers connect in one-on-one interactions that are not seen in public, Correa-Cabrera said. She added that Maldonado’s references to narcoculture do not add up, and do not reflect the realities of migration she has observed on the ground.

The jumble of generic references to different gangs in the account provide a “cartoonish version” of narcoculture, Correa-Cabrera said.

We contacted Maldonado by phone prior to publication to ask him about his TikTok account and the lyrics in his music.

He told us he helps people cross the US-Mexico border undetected.

Despite his statements on TikTok that his services were more expensive, he claimed he does not charge for his services, has no arrangements with organised crime and is motivated only to help people. He claimed a bad experience being smuggled twelve years ago motivated him to help others cross. We were not able to verify any of his claims.

“…. they threw me in the desert to walk, they left me there like a dog, walking for thirteen days without eating or drinking anything… and I said no!!! … I’m going to learn the routes and I’m going to cross everybody to the United States because this land also belongs to humans, God is not going to let other people suffer what I suffered. And that’s how it started.”

He told us the TikTok account was not monetised and the goal was not to recruit people but instead to alert and protect them from scammers. He added that he does not respond to questions via TikTok. Instead, he works through recommendations and word of mouth.

“It [the account] is not for business or anything like it.”

“If you go and see the comments people ask me for information, but I am not answering any of that.”

We told him we had geolocated him to the mangroves of Florida when referencing the border barrier in the Rio Bravo in one of his TikTok videos, and he told us that he previously lived in Florida.

We asked Maldonado whether he used semi-trailers for his smuggling services to which he answered: “No, I don’t work with that”.

Gang members reportedly ask migrants for a password that proves they have paid coyote networks to travel across Mexico and the US-Mexico border. We asked Maldonado about the meaning of the word “Omega” which is one of his nicknames and is repeatedly referenced in his songs as well as in migrant testimonials posted on his account. He told us he couldn’t talk about that.

Asked how he gets away with smuggling people without permission or being stopped by drug cartels, he said: “They can’t stop me. They call me the Phantom of Tamaulipas”.

This work was produced as part of a journalistic investigation coordinated by Noticias Telemundo and the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) with the participation of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), Bellingcat, Contracorriente (Honduras), Plaza Pública (Guatemala), EnUn2x3-Tamaulipas, Chiapas Paralelo and Pie de Página (Mexico). Legal review: El Veinte

Àngela Cantador and Pablo Medina from the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) and Akk36 from the Global Authentication Project contributed research to this piece.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Instagram here, YouTube here, Facebook here, Twitter here and Mastodon here.