As Cargo Flights Leave Kaliningrad, Air Defence Systems Disappear

In the late days of October and early November 2023, military cargo flights in and out of the Russian seaport city of Kaliningrad were at an uncharacteristic high. As the Kaliningrad Region on the Baltic Sea shares land borders exclusively with NATO member states and is home to Russia’s Baltic Fleet, it is of great strategic importance and of significant interest to flight trackers. This also means that flights from Kaliningrad to mainland Russia cross the Baltic Sea and international airspace — meaning that they often turn on their transponders.

In late October, social media users noticed an uptick in Russian military cargo flights, particularly of An-124 and Il-76 aircraft. Among them was a pseudonymous X account that goes by Markus Jonsson, which highlighted the anomaly with a graph using flight data from ADSBexchange showing fluctuations in weekly military flights dating back to 2021.

By using the ADSB exchange, Bellingcat was able to independently verify that An-124 and Il-76 flights had indeed left Kaliningrad throughout early November.

Konrad Muzyka, an independent defence analyst who studies Russia, suggested on X that it is likely the increased activity was in connection with the movement of military equipment.

Other users on X speculated about what cargo the planes could be moving, particularly the flights by the larger Antonov An-124 Ruslan planes,one of the largest heavy strategic military transport aircraft in use today. Users on X suggested that the cargo could contain S-400 missile systems bound for Rostov-on-Don after recent Ukrainian strikes using long-distance ATACMS missiles damaged Russian air defences in the occupied Luhansk region. On November 9, the UK’s Ministry of Defence wrote that in order to maintain coverage over Ukraine, it was “highly likely” that Russia would need to reallocate surface-to-air missile systems from elsewhere.

This prompted Bellingcat to investigate.

Bellingcat has found a marked change at two air defence sites in synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) imagery since the reported cargo flights, indicating that at least some of Russia’s S-400 batteries have indeed been moved away from their previous locations in the Kaliningrad Region. Where exactly they have gone remains uncertain.

Reflective Analysis

To test whether equipment was moved in Kaliningrad, Bellingcat referenced a map file of Russian military installations created by X user Archer83Able. Using the points indicated in the file, ten air defence radar and missile sites were inspected for change in November using Sentinel-1 (S1) SAR imagery.

S1 imagery is freely available for anyone to view and on a variety of platforms such as Sentinelhub’s EO browser. More widely known types of satellite imagery, such as that displayed in Google Maps’ satellite view, uses light cast from the sun and reflected off objects on the ground to create images. This is similar to how the human eye works, we rely on light sources to see. SAR satellites effectively act as their own sun, emitting signals onto the ground, and creating an image based on what is reflected back. This is similar to how a bat uses sonar to “see” in the dark.

Objects which reflect a strong signal back to the satellite will register as a high value and objects which absorb the signal or reflect it away from the satellite will register a low value.

The cloudy weather conditions in Russia in November mean that optical satellites have struggled to get good imagery of Kaliningrad, which is why S1 SAR images — which can see through clouds with little issue — are useful in this case.

To check for signs of change at known air defence sites in Kaliningrad, Bellingcat observed values collected by S1 at each site before and after the suspected late October movement period.

From these manual checks, two locations of interest were identified at air defence sites where returns were lower in November 2023 than in October.

These are shown on the map below in yellow. They are location A, which is a military base north of the city of Gvardeysk (54.6846473798, 21.0114129595), and location B, this one west of the regional capital inland from the Primorskaya Bay (54.7467259714, 20.0746540922).

This method alone was insufficient to determine whether the systems had moved. Low-resolution SAR like S1 can be good at showing when a SAR-reflective object is present but show with much less certainty whether such objects are not present. Many factor such as satellite angle and ‘noise’ can cause objects not to show up in S1 imagery.

In order to limit the possibility of false negatives, Bellingcat created aggregates from two to four separate days of before and after imagery to be used for comparison. The more imagery aggregated, the lower the chance of a false negative due to the combination of multiple passes. The downside of such a method is that it is less sensitive to short-term changes.

This means that such a method would be ideal if Russia moved material from a location in Kaliningrad and put nothing in its place, but would be less effective if the empty space was occupied by new objects. For example, this effect was visible at an S-300V4 site on the Kuril Islands near Russia’s de facto maritime boundary with Japan, where launchers and radars appeared to have been replaced by cargo trucks. This method is also unable to track the movement of objects, meaning equipment which had disappeared in one site may have been moved elsewhere in Kaliningrad rather than transported outside the region by aircraft.

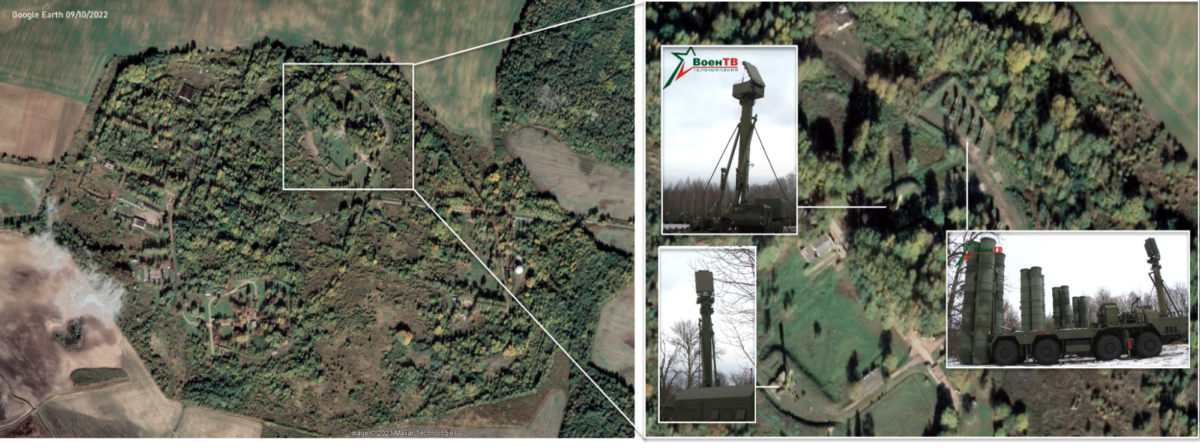

When creating these aggregates, two sites of particular interest became apparent. At one site near the Kaliningrad Region town of Gvardeysk and east of the regional capital points which had previously shown high returns in October appeared indistinguishable from regular noise in November. These points aligned with two radars and a row of launchers of an S-400 air defence system as seen on satellite imagery from October 2022. We have referred to this site as location A. We’ll examine two separate parts of this area — the northern and the southern anti-air batteries.

Systems like the S-400 are easily recognisable in imagery hosted on public mapping services like Google Earth due to their size. The S-400, for instance, involves a whole array of large vehicles including a mobile command post and reloading vehicle among others. These base maps can be used to determine the exact locations of individual objects to help interpret what the changes in lower-resolution imagery mean.

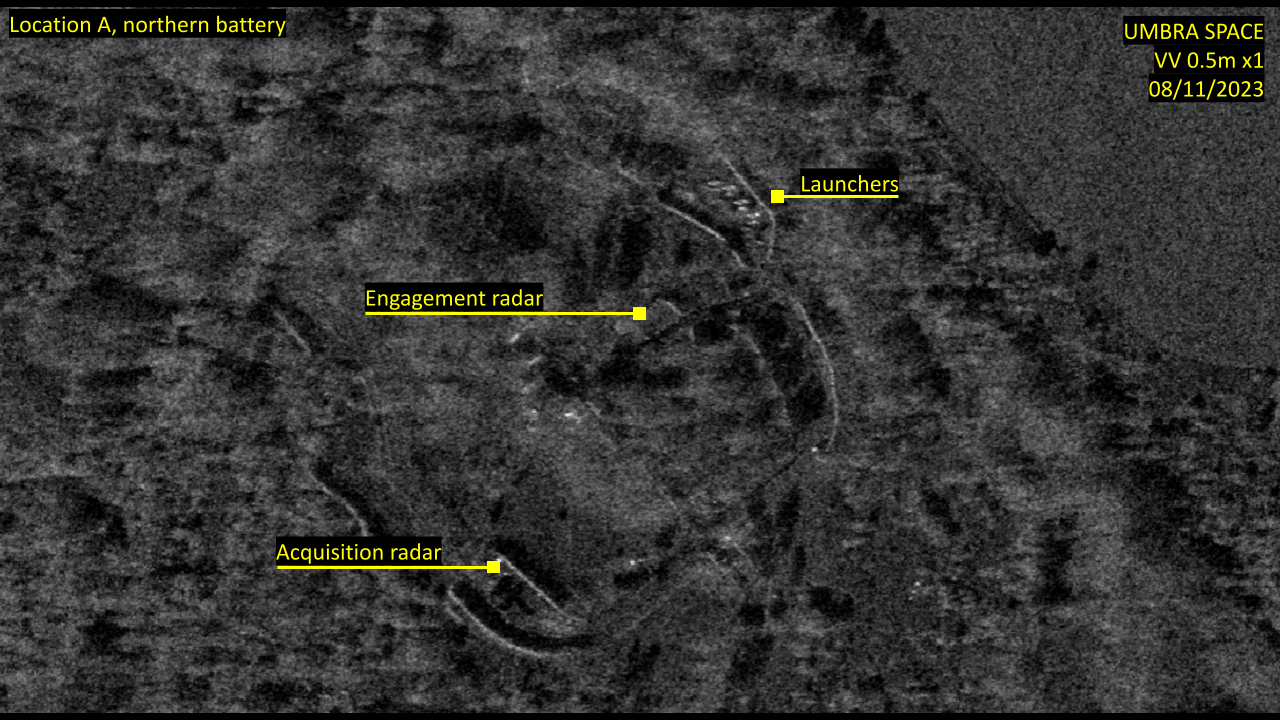

The two images below, for instance, suggest that the northern cluster of equipment — labelled launchers, targeting radar, and search radar — was removed from Location A (54.6846473798, 21.0114129595) at some point after October 2023.

Location A. Before – SAR imagery from dates in October 2023, After – Sentinel-1 imagery from dates in November 2023. overlaid on ESRI satellite imagery from March 19 2022.

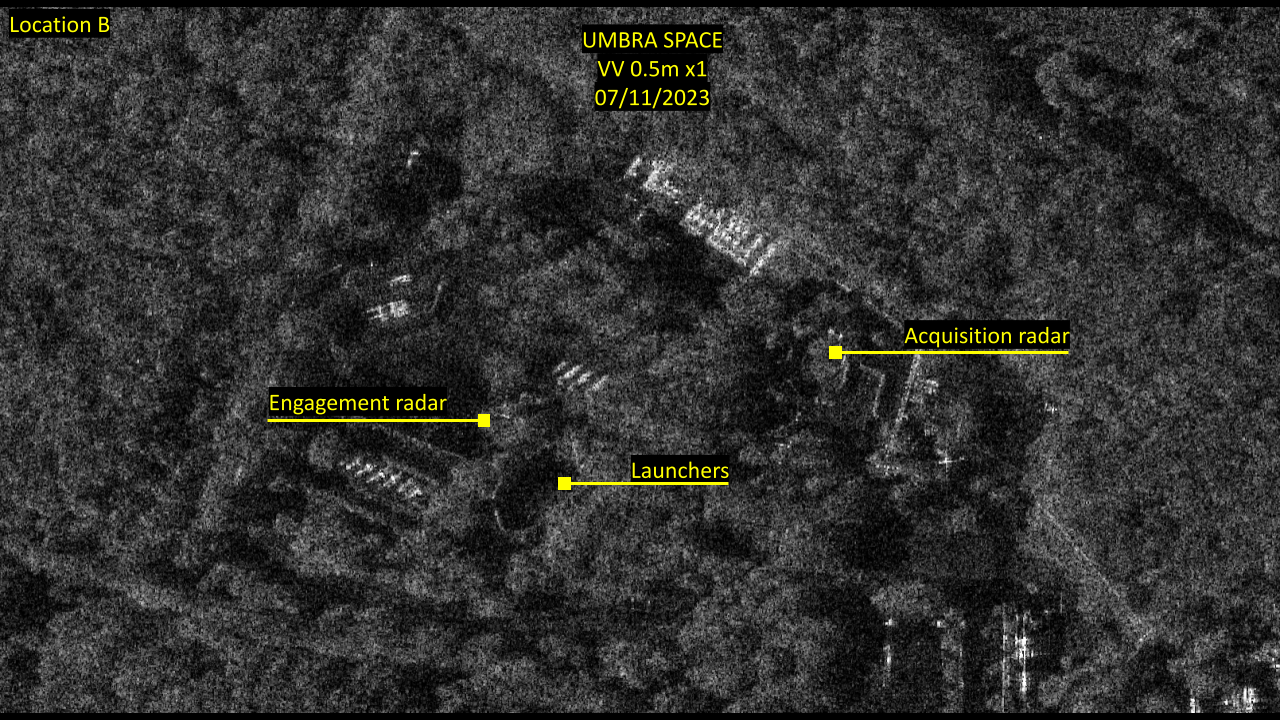

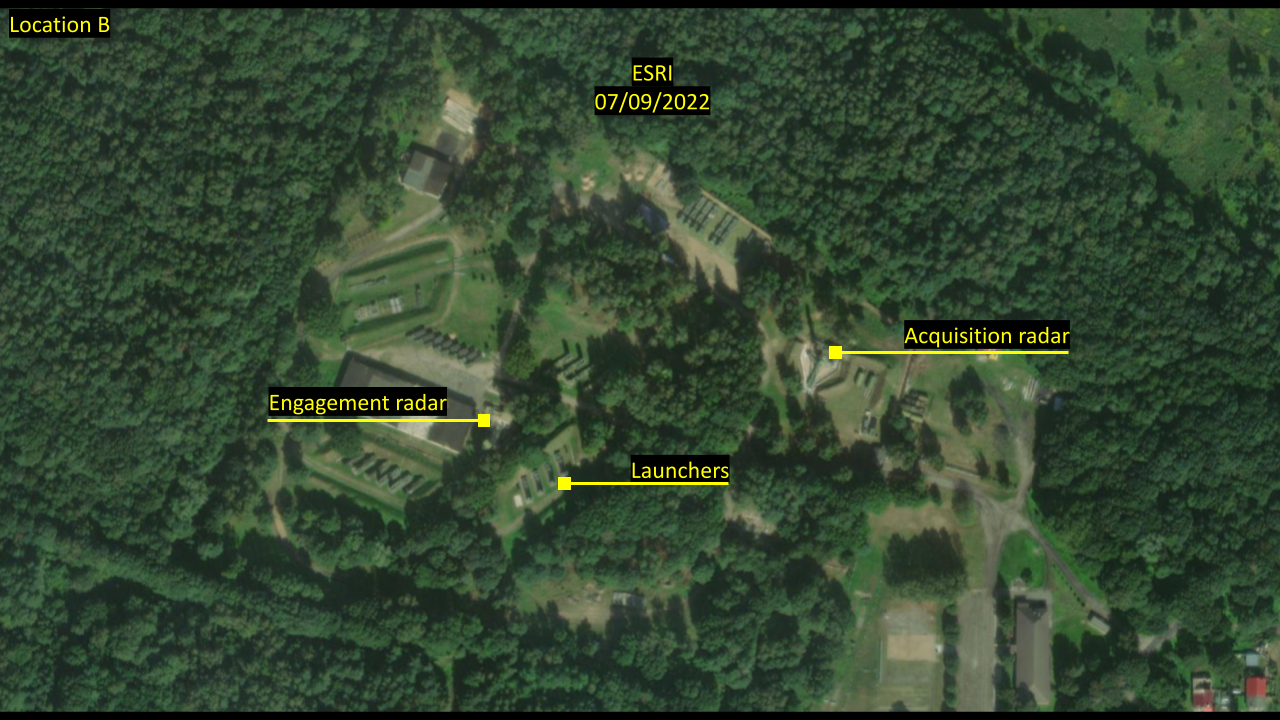

At another location, this one west of the regional capital inland from the Primorskaya Bay and referred to as location B (54.7467259714, 20.0746540922), returns from November appeared significantly lower when compared with October at points associated with launchers and radars in reference imagery.

Location B. Before – SAR imagery from dates in October 2023, After – Sentinel-1 imagery from dates in November 2023. overlaid on ESRI satellite imagery from September 7 2022.

A Second Satellite

Due to the low resolution of S1, and the possibility of the negative returns being related to factors other than the removal of the materiel, Bellingcat tasked high-resolution SAR imaging by Umbra to the area.

When reviewing the Umbra imagery, returns appeared consistent with the low-resolution S1 imagery for November. For location A, points that should have contained highly SAR reflective objects appeared dark. This was particularly true for the air defence radars at this location. The northern part of the site where the launchers were located had faint returns, and it was not possible to determine whether the launchers were still there.

Location A, northern battery. Umbra Space SAR imagery compared with ESRI base map from 2022.

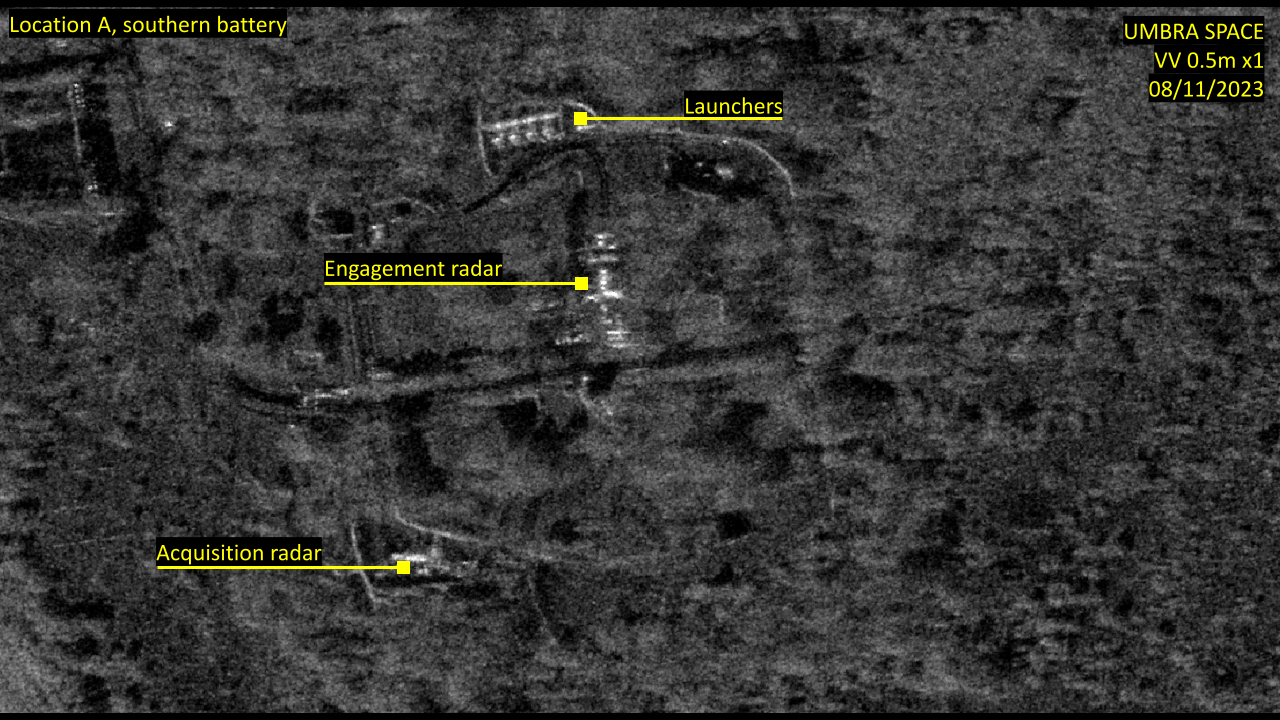

To illustrate what SAR imagery shows when the S-400s remain visible, let’s look at the southern anti-air battery at location A. Meanwhile, when comparing this change to the cluster of equipment at the same site that does not appear to have been moved, the difference becomes clear. Here the radar masts are still clearly visible in the SAR imagery, where they appear as some of the brightest objects along with the launchers.

Location A, southern battery, showing equipment that has remained in the area in Umbra Space SAR imagery compared with ESRI base map from 2022.

This high-resolution SAR imaging shows the shape of an S-400 air defence battery. When comparing it to the other battery at this site in true colour satellite imagery from 2022, it becomes clear that the northern battery was most likely vacated, at least partially.

While this evidence was straightforward, the results of the imagery at the second location of interest we found — location B — were less conclusive. This could have been because of the direction of the satellite and tree coverage, among other factors.

Location B. Umbra Space imagery compared with ESRI basemap from 2022.

This location’s returns were also consistent with the corresponding S1 imagery — points where values had dropped in November S1 imagery appeared dark in Umbra’s imagery. When compared to the battery at location A, higher returns would be expected particularly at the point of the acquisition radar, but instead very little is visible.

From this imagery, it appears plausible that air defence systems at locations A (northern battery) and B may account for at least some of the increase in heavy military cargo flights going in and out of Kaliningrad.

However, this can not be determined for certain and the contents of these flights cannot be determined without additional information.

To see the full dataset click here.