Frontline Facilitators: How Secretive UK Partnerships Supply Wartime Russia

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, UK Limited Partnerships (LPs) have been named as trade intermediaries in thousands of records detailing imports into the belligerent state. The UK has introduced a variety of sanctions aimed at negating Russia’s war efforts. However, experts have long argued these corporate vehicles — which are easy to set up and can be used to obscure ownership under the benefit of English common law — encourage unchecked illicit activity on global financial markets.

Bellingcat’s analysis of publicly available import and export records has revealed that:

- UK Limited Partnerships acted as intermediaries for over 17,000 imports into Russia between 24 February 2022 and 31 March 2023.

- None of these Partnerships have controlling partners or persons of significant control in the UK.

- More than 600 of these shipments concern items flagged by the EU and its partners as “High Priority” battlefield components, potentially dual-use and sanctioned items that could assist Russia in its ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

- 3,211 exports into Russia contained items included in the ‘universe of critical components’, a term the pro-Ukrainian International Working Group on Russian Sanctions uses to define components found on the battlefield.

“We have introduced the largest and most severe economic sanctions ever imposed on a major economy, significantly reducing UK goods being exported to Russia,” said a spokesperson for the UK Department of Business in a statement to Bellingcat. “Whilst we cannot comment on individual cases, we are clear that any UK company that is found to be selling or exporting sanctioned goods to Russia, directly or indirectly, could be in breach of sanctions law and could face a heavy fine or imprisonment.”

Last month, a government financial crime bill received Royal Assent, introducing new though yet-to-be-implemented regulations on LPs.

Through a series of simple searches on online import databases, Bellingcat discovered that Limited Partnerships (“LPs”), mostly registered in Scotland, have acted as intermediaries in over 17,000 imports into Russia since the war began. The widespread use of Persons of Significant Control (“PSCs”) outside of the UK and EU and controlling partners in secrecy jurisdictions makes any meaningful attempt to identify the true beneficial owners of these partnerships all but impossible.

The nature of these trades and the opaque nature of the Limited Partnerships involved raise questions about the efficiency of the sanctions regime in the United Kingdom. On 24 February 2022, Britain announced a raft of sanctions against Russia, including legislation to ban the export of “all dual-use items to Russia”.

Following this announcement, thousands of shipments ranging from car parts to electronics, timber, wines and tobacco were nevertheless imported into Russia using UK LPs as shippers. The PSCs of the Limited Partnerships involved, when listed, are largely based in Russia, Eastern Europe, or countries far beyond the reach of UK authorities. None are based in the UK and only a handful are inside the European Union (EU).

Obtaining these import records was straightforward and inexpensive. The data firm ImportGenius maintains a database of customs records across a variety of territories including Russia — the company sources its Russian trade data from legally obtained proprietary sources, according to its website. This database is searchable and the full dataset of Russian imports Bellingcat obtained was available for a fee of US$99.

A simple search for “LP” revealed tens of thousands of shipping records. To focus on imports made after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, only records registered after 24 February 2022 were used in this investigation. Up-to-date records are not currently available, and our research covers the period from the beginning of the war to 31 March 2023.

Cracking the HS Codes

An analysis of the Harmonised System (HS) codes attached to the shipments reveals the nature of the goods imported — HS codes are standardised numerical identifiers used for classifying traded products and overseen by the World Customs Organization.

Export rules are complex and it is difficult to ascertain which goods may be dual-use, a term for items that have both civilian and military uses, based purely on the codes attached to them and the exporter’s own description of the goods. Further complicating matters are the opaque nature of the LPs acting as shippers in these transactions.

However, the government’s own statements reveal that a number of shipments may require further scrutiny. The EU and its international partners list a number of HS codes which they considers “High Priority”, pertaining to items “found on the battlefield in Ukraine or critical to the development, production or use of those Russian military systems”. These include items such as ball bearings, static converters, television cameras, aerials, plugs and sockets.

Many of these items could clearly be seen in the content descriptions for the shipments seen by Bellingcat.

All of these shipments were arranged for export to Russia via UK LPs during the course of the first year of the war. During the Period, 678 exports to Russia were made under these codes utilizing UK LPs as shippers. Arrival dates provided in the data show that these shipments were successful.

On 28 August 2022, 5,000 kilos of static converters, devices that transform direct current into alternating current, and which appear on the High Priority list arrived in Moscow in a shipment facilitated by an SLP whose controlling partner is based in the Seychelles, and whose PSC is a Russian national. 146 separate shipments of static converters were made during the Period.

In a report published on 3 July 2023, the International Working Group on Russian Sanctions listed 385 HS codes making up the “universe of critical components”, components of dual-use items found on the battlefield in Ukraine. The Working Group consists of 60 pro-Ukrainian scholars including Stanford University’s Michael McFaul, a former U.S. ambassador to Russia.

During the Period, 3,211 exports with these HS codes found their way into Russia.

Bellingcat showed the details of the shipments to L. Burke Files, an independent financial investigator expert in illicit finance and who has studied UK and Scottish LPs.

“I found a lot of those HS codes extraordinarily disturbing,” said Files. “You know, thermal controllers for a sauna. Great, well that’s also what’s used in making explosives. You have to control heat and humidity. Dual-use? Yeah.” He added that the proliferation of Limited Partnerships, because of how easy they are to set up and shield offshore firms, makes it incredibly difficult for this activity to be scrutinized.

“This type of sanctions busting is complex and requires a team with many different disciplines— people who understand shipping law, maritime law and treaties,” said Files. “You’re trying to pull out an ounce of water that’s bad out of a raging waterfall. There are clues, such as when entities are set up in jurisdictions of convenience, and they should be checked more often.”

What is a UK Limited Partnership?

The majority of the Limited Partnerships involved are based in Scotland (“SLPs”). SLPs have legitimate business applications, but their opaque ownership, lack of filing requirements and tax transparency have been utilized in a litany of major money laundromats and a wide variety of illicit activity worldwide, dating back to at least 2014.

Previous reporting by Bellingcat, and other outlets has revealed that SLP numbers exploded in the mid-2010s, with at least 71% of SLPs registered in 2015 being controlled by partners in secrecy jurisdictions. These are territories whose regulations allow individuals or entities to evade regulations in other jurisdictions.

As such, SLPs have been a useful component in transnational money laundering schemes. They were involved in the Global Laundromat, moving between $20 billion and $80 billion out of Russia during a four-year period, the Moldovan bank raid, whereby $1billion disappeared from three Moldovan banks in 2014 and the Azerbaijani laundromat, a scheme where $2.9 billion was funnelled through European banks and companies.

“Since the beginning of the new millennium, UK Limited Partnerships have been targeted by global elites to help obtain and move corrupt funds through the financial system,” Graham Barrow, a money laundering expert and director of The Dark Money Files, told Bellingcat. “Whether it is setting up bogus companies to win government contracts in former Soviet states, to own significant assets as a way of masking ownership or for setting up bank accounts to move huge swathes of dirty money around the world, UK Limited Partnerships have been the ‘go-to’ entity.”

This has not gone unnoticed by the UK Government, which launched a public consultation into the reform of Limited Partnerships in 2018. Last year, the Government said it is “aware of reports that some limited partnerships have been abused… and intends to crack down on their misuse.”

New legislation, the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill, received Royal Assent on October 26, introducing regulations to LPs such as the need for partners to provide additional identifying information. However, these rules have yet to come into effect, and have not impacted the activities of any of the Limited Partnerships involved in this report.

“Given the almost negligible requirements at registration, and the lack of a requirement to file any accounts, it isn’t hard to see why” LPs have been used in illicit activities, added Barrow. “What’s harder to understand is the dilatory nature of the UK government response when it was clearly obvious to anyone who investigated their use how ubiquitous they had become within money laundering networks.”

Outsourcing Control

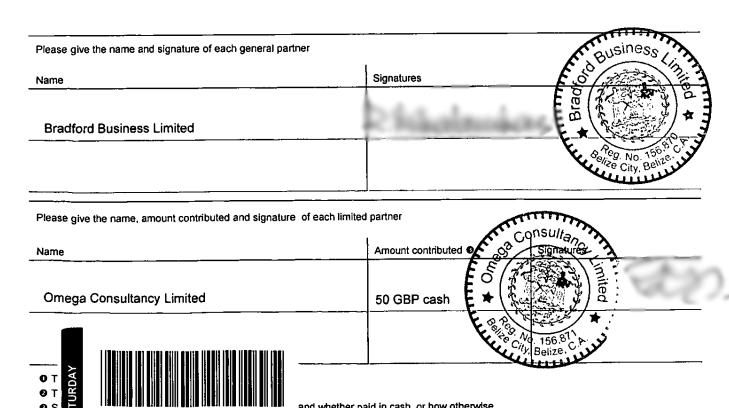

A total of 45 LPs in Scotland, England and Northern Ireland have acted as shippers in the export of 17,425 shipments during the Period. All have registered offices in the UK, but this is where any connection to Great Britain ends. None have either controlling partners or PSCs in the UK, the most popular origin for partners being the Seychelles, followed by Belize, with both countries accounting for 42% of the General Partners involved. Twenty-six per cent of controlling partners are based in Eastern Europe.

SLPs have limited filing requirements, not needing to file accounts, and are not subject to taxation in the UK. Partners pay tax to their own countries’ authorities. Therefore, despite the volume of these shipments, the UK does not benefit financially from the existence of these partnerships.

The same cannot be said for the Russian economy. Among the exports during the Period are over 5,000 shipments of wine. Although expensive luxury items are subject to export restrictions, based on their value, there is no evidence that any of these shipments meet that threshold. However, it is notable that the Russian state has raised the duty on imported wine from “hostile countries” during the course of the war (from 12.5% to 20%).

Some of the LPs in question highlight the need for reform. One SLP, naming another SLP as its Person of Significant Control (“PSC”) and controlled by a General Partner in Belize, has filed for dissolution three times, but has still found the time to ship four tonnes of pipe fittings to St Petersburg. Current rules, pending changes in the Government’s new bill, do not allow SLPs to be struck off the company register, meaning that SLPs can file for dissolution repeatedly whilst continuing to operate.

The most prolific LP during this period was Premium Trading International, a now-dissolved partnership based in Scotland. The partnership was controlled by a General Partner in the Seychelles and its PSC was a Russian national giving her correspondence address as a formation agent’s office in Edinburgh. The firm was set up in 2015 by Lawsons & Co, a now-defunct formation agent also responsible for setting up companies allegedly related to the 2014 Moldovan bank raid, the Troika Laundromat and the Russian Laundromat. It is not suggested that Lawsons & Co knew of the purpose of the many limited partnerships they formed nor the details of individual shipments.

During the period, Premium Trading International was named on the import records of 4,873 shipments to Russia, or 27.9% of the overall shipments during the Period. It acted largely as an intermediary between Chinese suppliers and Russian businesses. According to ImportGenius records, these shipments mostly consisted of a wide variety of car parts. The UK government’s own sanctions rules are complex and cover an ever-changing array of items, but potentially dual-use goods often require an export license. Under these circumstances, it is unclear whether the relevant authorities received licenses from the Russian PSC, the Seychellois partners or the Chinese importers.

Of the shipments made to Russia during the Period, a large proportion were components for the manufacture and maintenance of vehicles. These included cylinders, gaskets, parts of combustion engines, control panels, electrical circuit parts – covering a vast range of mechanical and electronic parts used in the manufacture of vehicles. Most of these parts do not appear on the EU’s “High Priority” list, but many do appear on the list of HS codes published in the July 2023 report by the International Working Group on Russian Sanctions.

The Government’s Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill, which will aim to address some of the issues surrounding Limited Partnerships reached Royal Assent on 26 October, and is expected to come into force in the coming months. The effect this will have on the widespread global abuse of corporate vehicles in the UK remains to be seen. Based on the open source data currently available, it is clear that in the first year of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, trade was still thriving.

“I just look at this stuff and I say, after 40 years in finance, 30 years in investigating, I can’t spot a gem, but I can smell a turd” said Files, the financial investigator.

Katherine de Tolly contributed research

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Instagram here, X here and Mastodon here.