Russia’s Ghost Ships and the Evolution of a Grain Smuggling Operation

On June 3, 2023, the Mikhail Nenashev was heading north in the Black Sea towards the Kerch Strait between occupied Crimea and Russia. The 169 metre-long handysize vessel has long been of interest to ship and sanction watchers. It is one of several that has been accused of transporting grain from occupied eastern Ukraine via the sanctioned Port of Sevastopol in Crimea.

According to automatic identification system (AIS) data, which allows the position of vessels to be monitored, Mikhail Nenashev’s destination was the Port of Kavkaz in Russia. That same AIS data suggests the ship waited in anchorage in the southern area of the Kerch Strait, in what is known as the Kavkaz ship-to-ship transfer area, between June 3 and 16.

But on June 16 it disappeared from ship monitoring services, going dark and creating what is known as an AIS gap.

There are many reasons for a vessel to not transmit an AIS position, some of which are legitimate, such as technical issues and concerns over safety. But the deliberate disabling of AIS without legitimate cause is considered a deceptive shipping practice. It is a common tactic for those evading sanctions or engaging in illicit activities.

Bellingcat checked satellite imagery from nearby Russian ports like Novorossiysk during this period but could not see a vessel that was an obvious match for the Mikhail Nenashev, which is identified by its unique International Maritime Organisation (IMO) number: 9515539. Satellite imagery from its last known coordinates in the Kerch Strait also drew a blank.

However, the Mikhail Nenashev had not disappeared completely.

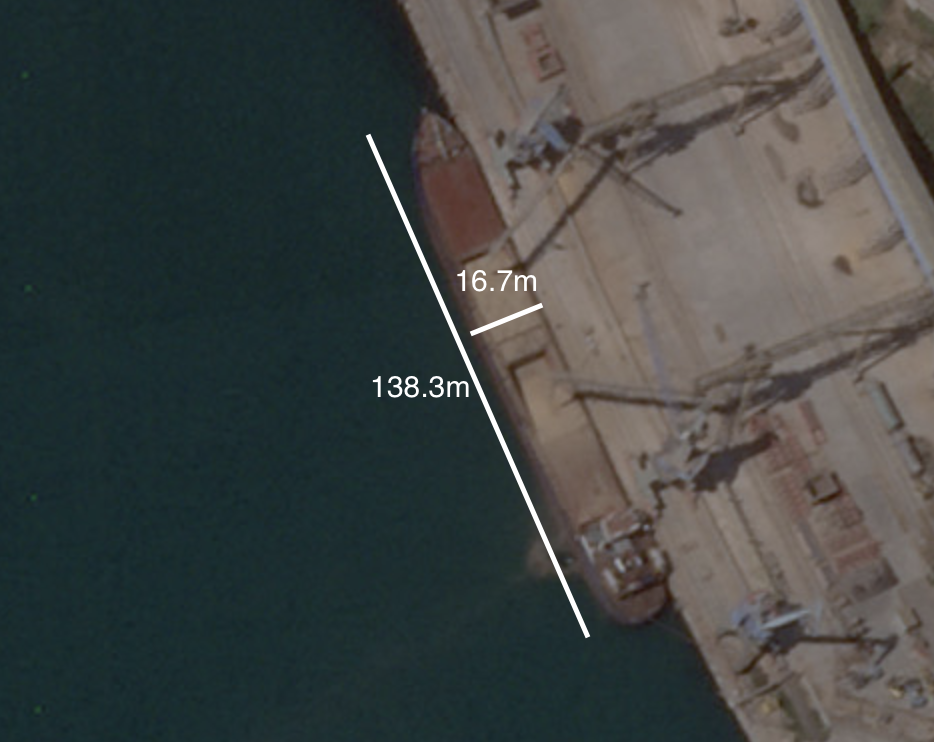

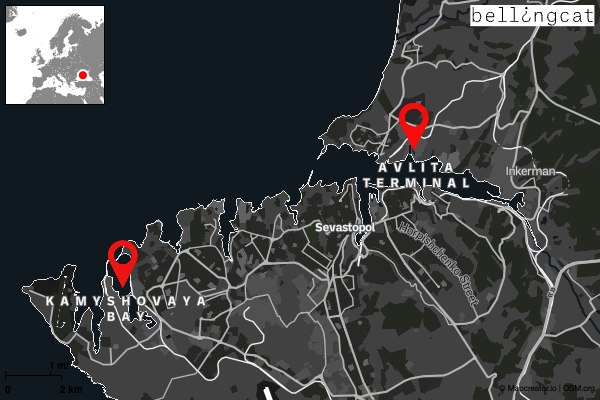

At the port of Sevastopol, just under a day’s sailing time away from the Kerch Strait, a bulk carrier that had the same dimensions, colourings and features as the Mikhail Nenashev appeared on satellite imagery outside the Avlita grain terminal – a site that has been targeted by western sanctions.

Between June 21 and June 24, it appeared that the vessel was being loaded with grain. By June 25 it was no longer visible in satellite pictures and a different bulk carrier was in dock at the terminal.

On June 26, the Mikhail Nenashev’s AIS signal re-appeared just south of the Kerch Strait as it headed back out into the Black Sea.

It was soon captured on film as it passed through the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey, on June 28.

AIS data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence showed that the Mikhail Nenashev crossed the Mediterranean on July 5 before entering the Suez Canal and making passage through the Red Sea. It headed east through the Gulf of Aden on July 12 before moving on towards the Persian Gulf.

On July 20, it arrived at its destination at the port of Bandar Khomeni in southern Iran.

Satellite imagery showed the vessel docked with its hatches open and grain seemingly visible. AIS data further confirmed its positioning there, and a comparison to the ship that had docked in Sevastopol again appears to match.

A change in draught from 9.6 metres when the Mikhail Nenashev entered Bandar Khomeni compared to six metres when it left suggests its carrying weight had decreased – likely signalling at least part of its cargo was offloaded there. Trucks lined up beside the vessel and grain spilled along the pier (which can be seen in the images above and a full size image here) also seems to signify this was indeed the case.

Bellingcat sought to ask Crane Marine Contractor, which operates the Mikhail Nenashev, about the vessel’s journey and what it was carrying but did not receive a response before publication. The ports in Sevastopol and Bandar Khomeini similarly did not respond to emailed requests for comment, nor did the Avlita grain terminal.

Grain Trail

Investigations in 2022 by the likes of the Financial Times, Bloomberg, CNN, Reuters, the BBC, the Wall Street Journal and Associated Press have all reported on grain being exported from sanctioned Crimea. Russia has previously denied exporting grain from occupied Ukraine and the Russian government did not respond to emailed request for comment regarding this article. But some in occupied Ukraine appear to have spoken openly about the practice. In June 2022, the head of Russian Crimea was reported to have stated that grain from occupied Kherson and Zaporizhya was being transported to and exported via Sevastopol. A March 2023 news report from a Sevastopol television station, meanwhile, detailed how grain grown in the occupied Melitopol region was being exported from Sevastopol. However, this is just a fraction of the full story.

Such actions are in contravention of United States, European Union and United Kingdom sanctions that have targeted exports from Crimea and Sevastopol. The UK has even specifically targeted grain stolen from eastern Ukraine.

A new investigation by Bellingcat, in partnership with Scripps News and Lloyd’s List, can further reveal:

- The identity of at least 10 ships that have surreptitiously visited Sevastopol to load up on grain. Some, although not all, are likely being looked at in detail for the first time.

- A small number of vessels have been going back and forth from Sevastopol to secretly deliver grain direct to ports. AIS tracking data, and previous media investigations, suggest these ships were likely going to Syria and Turkey in the first year of the invasion. But it now appears Iran is a destination for some of these vessels as well.

- Smaller vessels (each around 100m in length) transported grain from Sevastopol to the Kerch Strait, a narrow waterway situated between Crimea and Russia, where they performed ship to ship transfers with vessels that would then go on to deliver the grain elsewhere. This likely helped disguise the origin of grain from eastern Ukraine.

- An analysis of satellite imagery and AIS data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence shows that ship-to-ship transfers in the Kerch Strait have increased dramatically since the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion, although there may be several reasons for this

- Satellite images taken in 2023 show that Russian ships also appear to have been exporting grain from other ports in Crimea and other occupied territories such as Feodosia, Mariuopol, Berdyansk and Kerch

These findings appear to show the ever increasing complexity of Russia’s operation to move grain from occupied eastern Ukraine out into the wider world.

Russia recently exited the Black Sea grain deal that allowed certain agricultural products from Ukraine, one of the world’s biggest and most important grain exporters, to traverse the Black Sea unmolested. Since the collapse of the agreement mid-July the number of ships leaving from Ukrainian ports such as Odessa has come to a standstill.

But grain ships are still travelling to and from Russian ports, as well as sanctioned ports in occupied Ukraine. Ships taking part in journeys to and from the latter also continue to go to significant lengths to mask their operations.

Direct to Port

In many of the most prominent cases of grain being exported from sanctioned Crimea, media reports detailed how a fleet of handymax ships such as the Mikhail Nenashev, Matros Shevchenko (IMO: 9574195), Matros Koshka (IMO: 9550137) and Matros Pozynich (IMO: 9573816) were pictured in Sevastopol with their AIS disabled.

They would then head out into the Black Sea, where AIS would be switched on, before passing through the Bosphorus and sailing down towards the Mediterranean. AIS signals for these ships would consistently stop just north of Cyprus for a period of a few weeks before coming back online as the ships headed back north (with a lighter draught) towards the Black Sea.

Numerous media reports have suggested these vessels were headed to Syria. Interestingly, Syrian flagged vessels have also been spotted on satellite imagery loading grain at Sevastopol. The Souria (IMO: 9274331) and Finikia (IMO: 9385233), for example, were visible in images from Sevastopol observed by Bellingcat.

Some of these voyages were reported in the summer of 2022. The Financial Times, meanwhile, highlighted how a Russian vessel named the Fedor (IMO: 9431977) had seemingly transported grain from Sevastopol to Bandirma in Turkey. Sky News also reported tracking one journey made by the Mikhail Nenashev from Sevastopol to the Turkish port of Iskenderun. Bellingcat was able to identify the Fedor at Sevastopol on a number of other occasions as well.

By the summer of 2023, Bellingcat had spotted at least two vessels that appeared to have gone from Sevastopol to Bandar Khomeini in Iran. As well as the Mikhail Nenashev, AIS data and satellite imagery allowed Bellingcat to track the Matros Shevchenko all the way to Iran between early July and mid-August.

A satellite image (below right) captured on August 15 showed the vessel unloading grain at Bandar Khomeini. At this stage, the vessel had its AIS switched on. The key features of the ship, including the number of cranes, its colouring, fixtures and distinctive helipad matched on the ground images of the Matros Shevchenko, as well as satellite images of the vessel being loaded at Sevastopol a few weeks prior (where it kept its AIS switched off).

Both ships have a carrying capacity of 28,000 deadweight tons (DWT) so if they were operating at full capacity, and if they offloaded their full cargo, then 56,000 tons of grain from occupied Ukraine has been transferred to Iran in the last eight weeks alone.

Emails to the port of Bandar Khomeini as well as the port operator and terminal where the Matros Shevchenko was docked went unanswered. A number for the port operator was also disconnected. Like Mikhail Nenashev, The Matros Shevchenko is operated by Crane Marine Contracting which did not respond to request for comment.

Ship-to-Ship Transfers

On other occasions, Bellingcat and its investigative partners noticed a series of smaller vessels (roughly between 100m and 140m in length) pitching up at the Avlita terminal. Some of these are visible in the below interactive which details satellite image and synthetic aperture radar captures from the Avlita grain terminal over the first year of Russia’s full invasion.

Bloomberg reported last year that one of these vessels, the 115m long Amur 2501 had taken on grain at Sevastopol in early July before heading to the Kerch Strait where it conducted what is known as a ship to ship transfer, effectively offloading the grain it was carrying on to another vessel while at sea. This other vessel then went on to deliver its cargo, masking the true origin of its cargo.

A slight variation on this practice would see ships waiting in the Kerch Strait before taking on grain from vessels arriving from Sevastopol and ports in Russia’s Sea of Azov ports.

This scenario would see grain originating from both Ukraine and Russia mixed together on board before the receiving ship would head off to make a delivery. This practice likely further obfuscates the origin of cargo and allows Russia to disguise its operations in exporting grain occupied eastern Ukraine and Crimea.

The Wall Street Journal reported late last year that the 138m-long M.Andreev (IMO: 8946377) had met with the far-larger Emmakris II (IMO: 9254575) (which has since been renamed Ice Queen) in the Kerch Strait on June 14, 2022. The newspaper highlighted intelligence reports that placed the M.Andreev in Sevastopol in the days prior. Bellingcat analysed satellite imagery and found that a vessel consistent with the measurements and appearance of the M.Andreev had indeed been present in Sevastopol on June 13.

Following its ship to ship transfer with the M.Andreev, the Emmakris II appeared to conduct transfers with a number of other ships that had come from Russian ports.

In early July, Emmakris II set sail from the Kerch Strait, passing through the Bospherous and Suez Canal. However, it is not known where the Emmakris II unloaded its cargo as it switched off its AIS on July 22 just off the coast of Oman. It reappeared suddenly in the Persian Gulf at coordinates 27.24639, 51.93333 on September 5 before heading back to the Port of Novorossiysk in Russia. The UAE-based MFCC Shipping DMC, which was listed as the third party operator of the Emmakris II at the time, did not respond to request for comment from Bellingcat. Nor did the owner or operator of the M.Andreev.

Bellingcat and partners identified several other incidents where ships that had been captured on satellite imagery in Sevastopol turned up in the Kerch Strait a few hours or days later. It was not always possible to observe ship-to-ship transfers as, on many occasions, AIS appears to have been switched off by vessels while in the Kerch Strait. For example Lavrion (IMO: 8729195), a 115m vessel with a carrying capacity of more than 3,000 dead weight tons (DWT), appeared to have docked at Sevastopol on satellite imagery on August 8, 2022.

The ship (seen above) is the same length and breadth as the Lavrion. Key features – such as the number of holds, its colour, the shape of the bridge, the chimneys as well as the placements of the lifeboats – also match.

Furthermore, Lavrion was documented in an on the ground photo dated to August 8 that was uploaded to the Fleet Photo website (Bellingcat cannot embed this picture for copyright reasons). This image even showed grain pouring into the hold of Lavrion. However it was not possible to confirm where Lavrion delivered this grain or if it took part in a ship to ship transfer. Lavrion did not transmit AIS until three weeks later when it appeared to be operating hundreds of miles away in the Sea of Azov, likely returning to the Kerch Strait after visiting Rostov on Don in Russia.

It is important to note that only a small number of ship-to-ship transfers in the Kerch Strait appear to be suspicious or a possible exchange of grain coming from occupied Ukraine. The vast majority of vessels that enter the Kerch Strait to carry out transfers appear to be coming from Russia. According Alexandros Glykas, a director at Dynamarine co which specialises in risk assurance for ship to ship transfers, this type of transaction regularly occurs in the Kerch Strait due to draught restrictions and because many large vessels cannot traverse the shallower waters there. They therefore need smaller feeder vessels to bring cargo from the Sea of Azov ports like Rostov on Don out to them.

This supply chain has been in operation for over 20 years and is used to export oil and oil products as well as bulk commodities, mainly grain, to foreign markets. However, this highlights yet another difficulty in picking out those ship to ship transfers that may have originated from occupied Ukraine.

According to Glykas, the fact that there are so many legitimate ship to ship transfers occurring provides a useful cover for ships that are arriving from ports sanctioned by western nations in occupied Ukraine to carry out their own transfers.

Analysis by Bellingcat and its investigative partners, with AIS data provided by Lloyd’s List Intelligence and satellite imagery from Planet, found that since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine there have been over 6,000 ship to ship transfers carried out in the Kerch Strait.

New Tactics in 2023

Russia’s secret grain operation does not appear to have slowed down in recent months.

However, monitoring it in the same manner has become harder.

More and more ships appear to be turning off AIS tracking while in the Kerch Strait. This is perhaps understandable given the previous targeting of the Crimea Bridge and more recent attacks on a Russian tanker and warship at the nearby Novorossiysk port.

Rosmorrechflot, Russia’s Federal Agency for Sea and Inland Water Transport, was contacted about the significant decrease in AIS transmissions in the Kerch Strait but did not respond before publication.

Yet Bellingcat and its investigative partners also identified what appeared to be vessels loading grain at several other ports in either Crimea or occupied eastern Ukraine. Some of these observations seem to show evolving tactics for moving grain out of occupied Ukraine.

For example, a logistics route that ferries construction materials and agricultural goods between Mariupol and Rostov on Don was launched in May with the trade lane operated by RosKapStroy, a company that carries out construction work under Russia’s Ministry of Construction.

Vessels load building materials in Rostov which are delivered to Mariupol. The ships then return to Rostov loaded with grain from “the new territories of the Russian Federation”, according to a press release from RosKapStroy.

Russia-flagged 2,000 DWT general cargo ship Mezhdurechensk (IMO: 8948167) was the first vessel employed on this route, according to the press release.

Mezhdurechensk’s early journeys to the occupied port of Mariupol took place off the radar, with no AIS data available for the vessel during the periods it is thought to have docked at the port.

However, in recent months the vessel can be tracked for parts or all of its voyage between Rostov and Mariupol. A satellite image on July 29, 2023, showed Mezhdurechensk docked in Mariupol with its cargo hold open and a yellow, grain-like substance visible both inside and on the pier alongside it. Its position at the time the photo was taken matched AIS data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence.

Mezhdurechensk has made seven calls to Mariupol with its AIS on since mid-June, according to vessel tracking data.

It is not known where the grain that may have been carried by the Mezhdurechensk ended up after it was shipped to Rostov on Don. But it is noteworthy that many vessels depart from Rostov-on-Don before carrying out ship to ship transfers in the Kerch Strait. On other occasions, vessels coming from Rostov on Don make delivery direct to other foreign ports.

In Berdyansk, which like Mariupol looks out along the Sea of Azov, ships could be seen on satellite imagery. In early July, the self-proclaimed governor of the occupied Zaporizhzhia Oblast Yevgeny Balitsky stated on Telegram that dry cargo ships with grain were leaving the Berdyansk dock. Bellingcat saw ships docked there in satellite images.

However, it was not possible to identify any of the vessels from satellite imagery alone. No AIS signals were available for the position of the ships seen in satellites at the time they were taken.

In the Crimean ports of Kerch and Feodosia, meanwhile, ships could be seen loading yellow, grain-like substances throughout the summer of 2023. Several reports had noted these locations were being used to export grain from occupied Ukraine in 2022, but the process appears to be continuing. Bellingcat was able to obtain lower resolution satellite imagery of one of these shipments but other, higher quality versions are also available.

Interestingly, Bellingcat and its investigative partners noted fewer 100m to 140m vessels docking at the Avlita terminal in Sevastopol over the summer of 2023. However, larger vessels like the Mikhail Nenashev, Matros Koshka, Matros Pozynich and Matros Shevchenko all appear to continue to show up regularly in satellite images. This could suggest that fewer vessels are now conducting ship to ship transfers after docking at the Avlita grain terminal.

However, another section of the Port of Sevastopol appears to also be quietly attracting ships in the 100m to 140m size range. The pro-Ukrainian, and often controversial, activist website Myrotvorets reported in 2022 that ships appeared to docking in docking in Kamyshovaya Bay to pick up grain, something that was also noted in a report from the Initiative for the Study of Russian Piracy (which describes itself as “a group of former U.S. government officials, international trade experts, national security experts, and research analysts”).

Bellingcat and its investigative partners first noticed an 89m vessel with a carrying capacity of 2,700 DWT named Altarf had visited this location in late October and November 2022 with its AIS switched on. There was no available satellite imagery on the dates it visited to provide a visual confirmation of its presence. However vessel tracking data shows it did head towards the Kerch Strait after leaving Sevastopol on both occasions.

Throughout the summer of 2023, ships could be seen coming and going from Kamyshovaya Bay on satellite imagery.

As confirmation of the ship’s identities seen at this location could not be determined beyond doubt by time of publication, it was not possible to deduce or follow these ships to where their cargo had been delivered or exchanged.

AIS for these vessels remained switched off the entire time they were in Kamyshovaya Bay. Yet their presence, previous reporting and supporting satellite imagery, suggests this could be yet another exit point for grain coming from occupied Crimea. It must also be noted, though, that Kamyshovaya Bay is also reported to be a location where scrap metal and other goods are shipped from as well.

Bellingcat contacted the State Unitary Enterprise of the Crimean Republic Crimean Seaports, an agency of the local Russia-imposed authorities, to ask about the presence of ships at Sevastopol, Kerch, Feodosia, Mariupol and Berdyansk but did not receive a response before publication.

This report was compiled by Ollie Ballinger, Yörük Işık, Jake Godin, Bridget Diakun, Eoghan Macguire and Youri van der Weide, with contributions from Sophie Tedling, Teemu Nieminen and Timothy B from Bellingcat’s Global Authentication Project (GAP).

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here and Mastodon here.