Mapping the Aftermath of the Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan Border Clashes

In September last year, clashes broke out along disputed sections of the Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan border, affecting thousands of civilians. More than 136,000 people in Kyrgyzstan were evacuated during the clash, according to Kyrgyz authorities and an estimated 20,000 people were evacuated from districts of Tajikistan, according to the local branch of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent. A Human Rights Watch report released earlier this month documented the death of 37 civilians in the clash and accused both sides of committing apparent war crimes against civilians.

Increased militarisation along the border, the involvement of heavy weaponry and the damage to civilian buildings and infrastructure marked what experts on the region called an escalation in “intensity and consequence” from clashes of previous years.

To help assess the impact of these events on civilians, Bellingcat has created an interactive map showing apparent changes to buildings after the clashes, identifying civilian infrastructure and private property that was likely impacted. While our analysis does not show who may be responsible for changes to the buildings, it adds to research by Human Rights Watch which found that civilian infrastructure and properties were deliberately destroyed in several villages within Kyrgyzstan.

You can explore the map here:

Using Google Earth Pro, NASA FIRMS, Planet Labs satellite imagery and social media and media footage, Bellingcat surveyed areas of interest, highlighting where changes to buildings can be observed on satellite imagery. Where possible, we have geolocated incidents using available social media and other film footage. However, heavy restrictions on media and social media in Tajikistan meant that limited posts were available from the country. In other cases we identified buildings of interest where change was observed in satellite imagery but further investigation is still needed. The changes to buildings observed on satellite imagery does not provide conclusive proof of damage caused during the clash — but provides a starting point for investigation for researchers interested to see areas of potential impact from the clash.

In some cases we had access to high resolution satellite imagery from the days immediately before and after reported clashes. We also obtained and viewed lower resolution satellite imagery that, while more frequent, provided less granular detail. It is also possible that satellite imagery has not captured every instance of damage. Thus, the map we have created presents a detailed, if incomplete, picture of areas where changes to buildings occurred during the clash. What it does show is that in 11 villages and one city in Kyrgyzstan we observed change to 379 buildings and changes to 19 buildings in four villages in Tajikistan, in the days after the clash. Bellingcat contacted both the Tajik and Kyrgyz foreign ministries about our findings. At time of publication the Tajik foreign ministry had not responded. The Kyrgyz foreign ministry did not respond directly to our questions at the time of publication but referred us to their recent response to Human Rights Watch. In a letter sent April 11, 2023 to HRW, the government of Kyrgyzstan said that a total of 418 residential and other buildings and 27 social facilities, including 12 schools, 9 kindergartens, and 6 medical facilities “were burned… during the armed aggression by military personnel and illegal armed groups from Tajikistan.”

A History of Clashes

The Batken Region is in the westernmost region of Kyrgyzstan and is bordered by Uzbekistan to the northeast and Tajikistan to the northwest, south and west; it includes two enclaves belonging to Tajikistan, as well as a number of enclaves belonging to Uzbekistan.

Only about half of Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan’s almost 1,000km border has been demarcated since the collapse of the Soviet Union and independence. The borders in the region were delimited under Soviet rule and produced a complex, disputed border; since independence in 1991 disputes over access to natural resources and increased militarisation of borders has further increased tensions. As Bellingcat has previously written, water access has been one ongoing issue in the border region. Estimates vary, but RFE/RL reports that there have been more than 100 border incidents between the two countries since independence.

In the most recent clash in September 2022, both sides reported civilian homes and buildings were burned down and have accused each other of starting the dispute and of “armed aggression.”

How Did We Examine the Aftermath?

As multiple villages were affected, many with similar names, it was initially difficult to identify possible incidents and map them all out. To map out areas of potential damage we followed the steps outlined below.

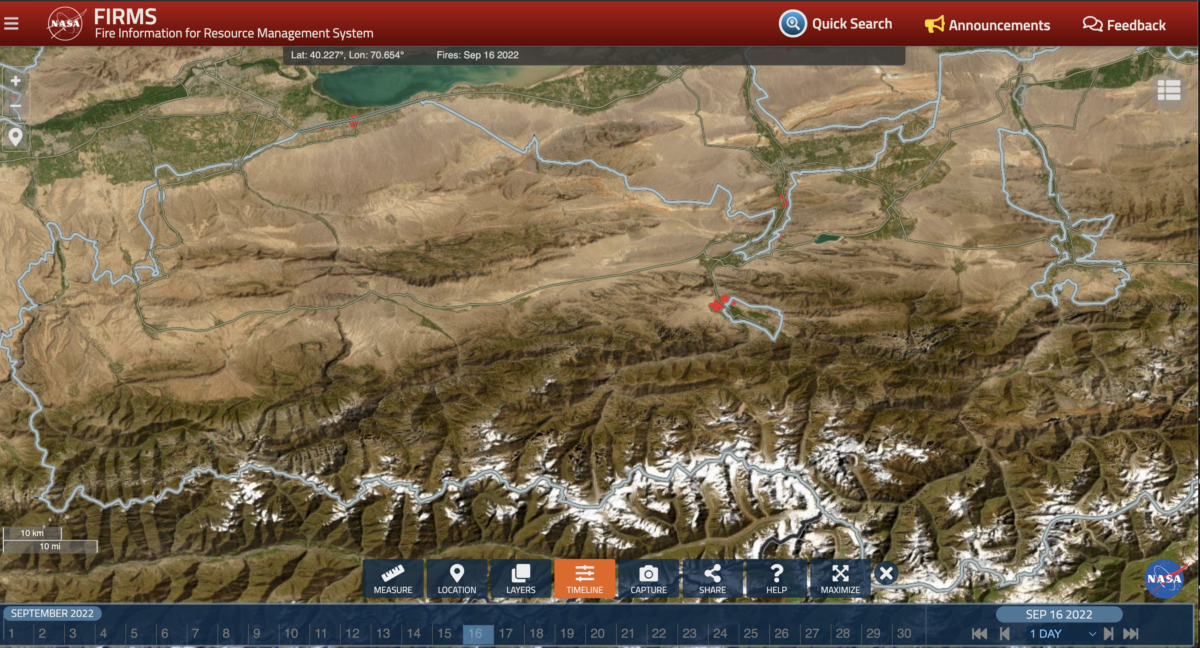

Many houses were reportedly burned down during the clashes, so the first thing we did was use NASA FIRMS to identify thermal hotspots that could be the result of fires caused during the clash, a methodology Bellingcat has previously outlined here. A number of intense clashes occurred on September 16 and NASA FIRMS was particularly helpful in identifying large areas of possible damage on that day. We thereby identified 10 border villages where thermal hotspots could be seen. It should be noted, however, that NASA FIRMS hotspots do not exclusively represent fires and could be the result of non-conflict related activities as well. Generally, NASA FIRMS is good at detecting large areas where there are thermal abnormalities that could indicate a fire — but it will not always show smaller ones and will not show individual buildings — so we also used other information sources to identify additional areas where damage from clashes was reported.

Digging into the Satellite Imagery

We turned to Google Earth Pro and Planet Labs Imagery — using rough coordinates from thermal hotspots identified via NASA FIRMS as well as areas reported via other open sources. The dates of available high resolution satellite imagery from before and after the clash varied. In about a third of cases we used satellite imagery from the day of or immediately after the clashes. Others were captured days or weeks after. In two cases, the gap of available satellite imagery was approximately a year and a half. We always sought to use the highest resolution satellite images available for each potential incident.

One interesting detail that emerged during this research was that it was possible to see that many of the same buildings in the village of Maksat, Kyrgyzstan, were likely impacted in previous clashes as well as those that took place in 2022. We found that 17 buildings in Maksat were no longer visible on satellite imagery taken eight days after the April 2021 border clashes, indicating their possible destruction. Satellite imagery shows those same buildings were rebuilt in the second half of 2021. However, they were once again no longer visible on satellite imagery taken after the September 2022 clashes.

To account for the different dates of available satellite imagery – and to further establish that the change to buildings occurred during the clash – we also looked at PlanetScope Scene imagery from Planet Labs. The resolution (three metres) on PlanetScope imagery is lower than on Planet’s SkySat offering (0.5m), or on some imagery available on Google Earth Pro, but the frequency of images it captures is far superior. Thanks to PlanetScope imagery, we were able to identify smoke rising above the villages on the day of reported clashes. This also allowed us to compare images from the day before and after the clashes which made it easy to detect pixels – likely representing buildings – disappearing. In some areas, where several buildings were destroyed or where there were red or brown-roofed houses which blurred into the background in the lower resolution images, it was difficult to see individual buildings change. Taken with the fact that a pixel represents a building this creates a small margin for error with this method.

The change in pixels – likely representing buildings- can be seen on PlanetScope satellite imagery over Kapchygai village. The first image is from September 15, 2022 and second is from September 17, 2022. Credit: PlanetLabs PlanetScope Scene.

Geolocating Damage to Buildings

Bellingcat was also able to geolocate seemingly damaged buildings by examining social media posts and media footage published by various news media that depicted the aftermath of the clashes. It should be noted again, that Tajikistan’s restrictive media environment meant there were limited open sources to examine from this country. In contrast, several Kyrgyz and international media outlets toured damaged areas in Kyrgyzstan following the clashes, providing ample video and photographic evidence for researchers to identify. This was therefore not a comprehensive analysis, but it allowed us to geolocate a number of buildings which were apparently damaged in the clash and link them to changes observed via satellite imagery.

For instance, we were able to geolocate a number of damaged buildings in the village of Dostuk using social media footage filmed after reported clashes. On September 19, a three minute video was posted in the pro-Kyrgyz Telegram channel “Border.” The person filming states in Kyrgyz; “here is my village,” and proceeds to pan the camera across a row of destroyed buildings. The person filming appears to be accompanied by an armed Kyrgyz soldier.

The footage reveals a street sign for “Abdiraim Kazy Street,” however looking up this street name on Google Maps, Yandex and 2GIS (a mapping service popular in Kyrgyzstan) did not yield any results. However, a smaller sign can be seen on one of the building’s fences; though very blurry, “Достук-3 25” can be made out, which transliterates as “Dostuk-3 25.” Though the address does not come up in any map services, it gives us a big hint that this footage was shot in Dostuk village. There are two villages named Dostuk in Batken, Kyrgyzstan, and Google street view is not available for either of them. However, by looking more closely at the buildings in the footage as well as the shape of the mountains in the background of the footage and other geographic features and objects, we were able to match it to the features observed via satellite imagery of Dostuk village located approximately 16 km west of the city of Batken, Kyrgyzstan.

There were several cases where we found evidence of damage to buildings and infrastructure, including bridges and border posts but have not included it in the map due to the lack of recent high quality satellite imagery. Yet these and other incidents merit further attention.

Since the escalation the two sides are reportedly in the process of negotiating the demarcation of the long disputed border and re-opening border crossings which have been closed since 2021. Previously negotiations between the sides have stalled over disagreement over which Soviet-era maps to use. It remains to be seen whether progress will be made, allowing people living in border regions an opportunity for better security in the future.

Narine Khachatryan contributed to this report and Miguel Ramalho from Bellingcat’s Investigative Tech Team built the interactive map. Bellingcat’s Global Authentication Project volunteers also contributed research for this piece.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here and Mastodon here.