Russia’s Assault on Daily Life in Ukraine

When a Kh-22 missile slammed into a residential apartment block in the city of Dnipro on January 14, it killed nearly 50 civilians and wounded dozens more. It was one of the largest such attacks since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine which Russian President Vladimir Putin launched one year ago today.

Russia’s destruction of residential buildings, hospitals, schools and power infrastructure have been widely reported in the period since.

Speaking at an awards ceremony on December 8 Putin, champagne glass in hand, acknowledged and sought to justify Russia’s campaign to destroy Ukraine’s energy infrastructure in what was widely considered to be a bid to break the country’s resolve. So far, those ambitions have failed.

But as Bellingcat’s project to map and log incidents of civilian harm in Ukraine shows, many other facets of civilian life have also been attacked.

They are the bus stops where people wait at the start of a working day, the playgrounds where they take their children and the post offices where mail parcels and letters are processed. Open source imagery – videos and photos from Ukraine, collected and verified by Bellingcat’s Global Authentication Project – tell the story of these key amenities and the citizens killed while using them.

Each of the codes given in brackets corresponds to a verified incident on Bellingcat’s TimeMap, which you can explore further here. At the time of publication, more than a thousand incidents are recorded on the map.

Heading to Work

Ukraine’s metro systems, which tunnel deep beneath three of its largest cities, have sheltered thousands of civilians during Russian attacks. They’re emblematic of the country’s resilience, despite also being a target themselves on a number of occasions. But above ground, tram, trolleybus and bus stops can be far riskier – single strikes can and have killed dozens of commuters who congregate on the side of a street.

One small group was waiting outside Kharkiv’s Pedagogical University on the morning of July 20 (CIV1195). They stood at the Barabashova Street bus stop, at the intersection of two busy streets. They’d have had a view of the Vesuvalny canal, which flows into the Kharkiv River and then through the centre of Ukraine’s second-largest city.

All were killed at 9:30 AM by what the authorities said was an ‘Uragan’ multiple launch system. According to the prosecutor, among the victims were a 72-year old woman, a 13-year old boy and his 15-year old sister. Photos shared by local media show the skeleton of the metal bus stop and a number of bodies.

Similar stories can be found across Ukraine.

For example, on the afternoon of March 15, three people sat in heavy coats in a bus shelter outside the town of Velyka Dymerka, just north of Kyiv (CIV0373). They were huddled in heavy coats, as is normal for Ukraine in March.

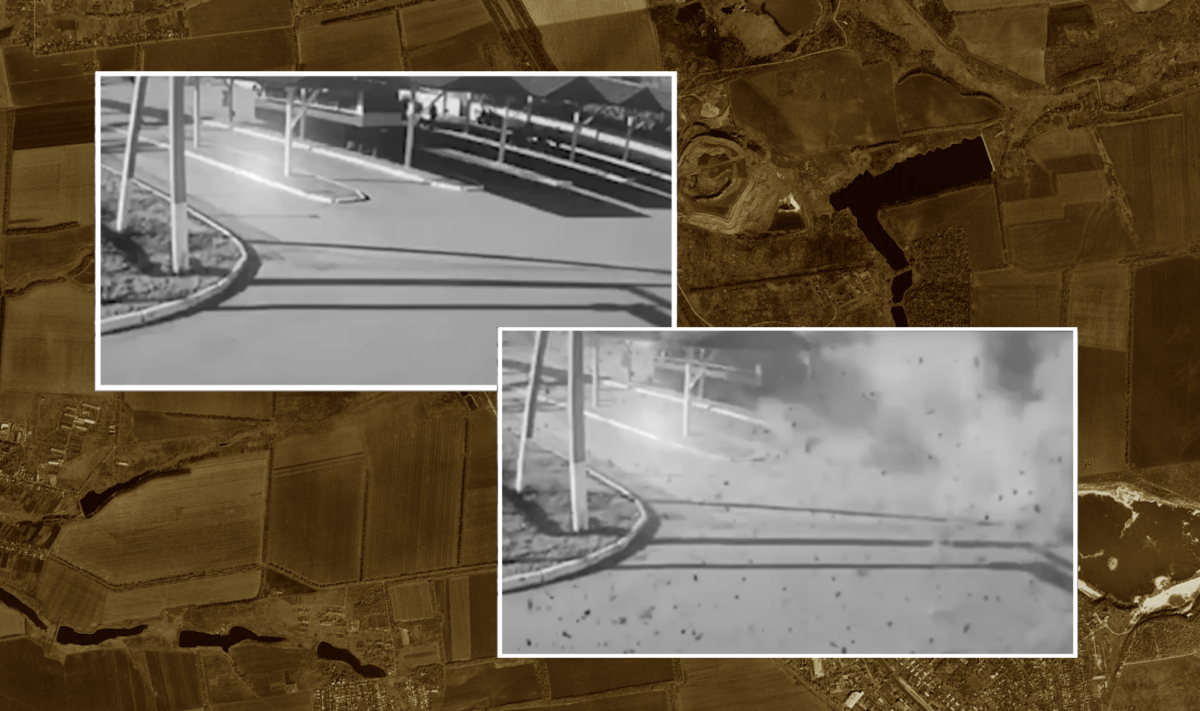

What happened next was captured on what appears to be CCTV footage. First, an orange flash can be seen behind a row of trees in the distance. The explosions come closer. One strikes just in front of the bus shelter and another behind. One of those waiting makes a move just before smoke fills the bottom half of the screen. Another figure runs out of sight.

This video was published on the InsiderUA Telegram channel. It is unclear whether any of the people featured survived. The local outlet BrovaryMedia commented under a Facebook post of the same footage that police had been unable to retrieve the bodies given that the town was occupied by Russian forces at the time of the event. According to reporting by Gazeta.UA, Velyka Dymerka was liberated on April 1.

The next month in an area of the Donetsk Region under government control, 10 workers stood in front of a bus at a platform at the massive Avdiivka Coke Plant. It was the end of their shift. CCTV footage shows an explosion almost directly in front of them. The screen soon fills with smoke. Citing police statements, the news website LB.UA wrote that seven workers were killed and 19 wounded in this May 4 attack. In press images, broken glass and bloodstains can be seen over the tarmac. Police shared an image of a munition fragment consistent with a BM-21 rocket.

As Russia’s invasion has dragged on, such attacks have continued. Extremely graphic images appeared online following an attack on a Mykolaiv bus stop on July 29 (CIV1235). Sevenwere killed and 19 hospitalised in this attack, according to the city’s mayor Oleg Senekevich.

On February 21 this year, as Putin gave a speech marking a year of his ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine, a rocket struck a bus stop in Kherson. Ukrainian officials said that it killed six people.

All in all, at the time of publication, Bellingcat’s TimeMap has recorded 19 attacks on public transport and transport infrastructure. This number includes cases in territories controlled by Russia such as an attack on a Donetsk bus station on July 14 (CIV1193). The full number of deaths from these incidents is not known; Ukraine’s Ministry of Infrastructure could not respond by press time.

Posting a Letter

Even in the digital age in a country which has taken steps to digitise its bureaucracy, snail mail remains a vital mode of communication. Ukraine’s state postal service Ukrposhta has even issued stamps glorifying the country’s resistance to Russia’s invasion. Yet the service has, understandably, been severely impacted by the war.

On the afternoon of April 15, a cruise missile struck a postal sorting centre in the Pivnichniyy District of Mykolaiv. For months, the southern Ukrainian port city was on the frontline as Russian forces attempted to advance west of Kherson (CIV0784). Mykolaiv was heavily bombarded; as Bellingcat has reported, at the start of the month a hospital and markets came under attack from rocket artillery stationed in the Russian-occupied Kherson Region.

Images shared on Telegram by Mykolaiv Region Governor Vitaly Kim showed the aftermath. One picture from the scene showed the head of a cruise missile. Conveyor belts for letters and parcels are warped out of shape, with red metal sorting boxes strewn throughout a hall of twisted metal. It’s new equipment; according to a local news website, this postal logistics terminal had opened in 2021. The same day Volodymyr Popereshnyuk, co-owner of the Nova Poshta company which owned the facility, wrote on Facebook that no staff had been killed but three were hospitalised after the attack.

Ukrposhta’s General Director Igor Smelyansky told Bellingcat that he estimated more than 500 postal branches could have suffered anything from light damage or been entirely razed to the ground since February 24. “We can only guess about the number since we do not have access to those in occupied territories such as Mariupol”, he cautioned.

Postal workers face the same risks as the rest of Ukraine’s civilians, Smelyansky explained. “There are losses of life when people are in their homes. People are killed when they go home at night because there’s no light”, he explained, adding that only two postal staff have been killed in the line of duty.

He referred to a case on March 5 in the Zaporizhzhia Region. Two postal workers were driving around small villages delivering pensions to local people. According to Ukrainian media reporting, citing government sources, the postal workers had encountered a group of pro-Russian Chechen fighters who shot at their car before crushing it.

A single photo which is extremely graphic is the only open source evidence of these events. Two bodies lie on the roadside, surrounded by papers. A crushed car lies behind them. The image was reportedly taken by other postal workers who left before they could retrieve the bodies, due to the presence of Russian troops in the area. As the Ukrainian press’ account of these events could not be independently verified using open source research, it cannot be found in Bellingcat’s TimeMap.

Post offices, like many other commercial or administrative spaces, have also reportedly served as humanitarian centres since the start of the invasion. On March 24, Ukrainian media reported a Nova Poshta facility in Kharkiv’s Saltivka district had been hit alongside other buildings, which according to the local prosecutor killed three and injured eight (CIV0533). Bellingcat’s Michael Sheldon assembled a Google Map showing missile impacts related to this incident, in which the motor section of a rocket slammed into a crowd of people waiting for aid outside the postal building. The previous day, the Russian military blogger Rybar alleged in a Telegram post that a Ukrainian military presence had been sighted in the immediate area, later providing inconclusive evidence for the claim.

Ukraine’s postal infrastructure continues to suffer as Russia’s invasion grinds on. On February 12, Suspilne Media reported that a Nova Poshta depot near Kharkiv’s Balashivskyi railway station was struck by an S-300 surface to air missile (CIV1858).

Having Fun

“This playground had a castle and a locomotive. Now it has a rocket”, wrote the journalist Alec Luhn on Twitter. In the image he shared on February 27, the motor section of a rocket can be seen embedded inside a children’s playground in the Saltivka district of Kharkiv (CIV0448).

Just two days earlier, a 9M55K rocket was photographed stuck in the ground near a grove of trees just in front of another playground in Saltivka (CIV0460). And again on March 6, the playground of a courtyard in the same block as that referred to in Luhn’s Tweet was struck in the same manner; a rocket was photographed sticking out of the ground just metres away from another train-shaped climbing frame (CIV0266).

These are just three of the dozens of images of destroyed children’s playgrounds in Ukraine which have been shared online over the past year. It is hard to establish with any certainty whether these playgrounds were attacked deliberately. However, it is clear that they are not being excluded from Russia’s indiscriminate bombardment of Ukraine’s cities, from which the Kharkiv district of Saltivka has suffered particularly badly.

In Ukraine’s cities, children’s playgrounds are often situated in courtyards between large Soviet-era apartment blocks. Even if such rockets do not strike these residential buildings, impacts such as those seen here would also damage cars, local shops, residential buildings and kill or maim passing pedestrians. Detonating cluster munitions would harm civilians over a wide area, regardless of whether the rocket was aimed at a civilian building.

Indeed, the Smerch and Uragan rockets seen in these images are capable of carrying cluster munitions. This weapons system deploys a large number of smaller sub-munitions over a target, which in turn spread and explode over a larger area. This increases the potential for casualties as unsuspecting civilians – including children – trigger the devices.

An example of this risk can be seen last April, when the prosecutor’s office in the Sumy Region shared an image of a rocket lying behind a tree in a playground in the town of Akhtyrka (CIV0754). The spent cargo section, which has deployed its submunitions, can clearly be seen. Submunitions were also attached to the Tochka ballistic missile which struck a playground, residential building and three cars in Mariupol in March (CIV0139)

At the time of writing, Bellingcat’s TimeMap database includes 13 incidents of attacks on children’s playgrounds across Ukraine, including one case from occupied Donetsk in August 2022 (CIV1242) and a cruise missile strike on Shevchenko Park in the very heart of Ukraine’s capital Kyiv in October (CIV1506).

The Human Toll

On February 21, the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk said in a statement that the agency had verified 8,006 civilian deaths and 13,827 injuries in Ukraine since Russia’s full-scale invasion. “Nearly 18 million people are in dire need of humanitarian assistance and nearly 14 million have been displaced from their homes”.

Many of these deaths and injuries are documented in Bellingcat’s database. But it is important to note that open source imagery likely represents only a fraction of the harm caused to civilians by Russia’s invasion.

Other facilities to be struck, and included in Bellingcat’s civilian harm database, include psychiatric hospitals (CIV0445), fire stations (CIV1040), religious (CIV0370) and commercial sites (CIV0894).

The prevalence of certain types of imagery online can also reflect what people on the ground in Ukraine feel is most important to share with the wider world. In the case of destroyed playgrounds, they are shared to demonstrate the attackers’ disregard for human life. The reception to Luhn’s Tweet is a case in point.

According to Yulia Gorbunova, Senior Researcher on Ukraine at Human Rights Watch (HRW), incidents of indiscriminate attacks on civilians in Ukraine could amount to war crimes.

“Under international humanitarian law, parties to an armed conflict must distinguish at all times between civilians and combatants, between civilian objects and military objectives, and take precautions to protect civilians. Failure to observe this principle — either by directly targeting civilians or civilian objects or by conducting indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks — is a war crime when committed deliberately or recklessly. Unlawful and wanton excessive destruction of property that is not militarily justified is also a war crime,” said Gorbunova.

“Additionally, explosive weapons with wide-area effect should not be used in populated areas. Their use heightens the likelihood of unlawful, indiscriminate, and disproportionate attacks and civilian harm, including commuters,” Gorbunova added.